27

When Should Epilepsy Neurosurgery Be Considered, and What Can It Accomplish?

A substantial minority of people with epilepsy continue to have seizures despite appropriate medical management. Although surgical techniques have been shown to reduce or eliminate seizures in this circumstance, epilepsy surgery remains underutilized, with only a small fraction of potential candidates referred to comprehensive epilepsy surgery programs. Because surgery for these patients often provides the only realistic possibility for seizure control, it is important that practitioners identify and refer these patients. Recognizing a surgical candidate requires knowing when further medication changes are not likely to be beneficial. It also requires an understanding of the various types of surgical treatment available as well as the expected risks and benefits of these treatments.

When are medication changes unlikely to bring seizures under control?

Pivotal, community-based studies demonstrate that half of all people with newly diagnosed epilepsy will be seizure-free with their initial anticonvulsant treatment. Of those who continue having seizures, only 10% come under complete control with the next medicine. Even after treatment with multiple medications or combinations of medicines, roughly a third of patients will continue to have at least some seizures.

From these findings, we can reasonably infer that medication trials quickly reach a point of diminishing returns, at least for the prospect of eliminating seizures. Does this mean that it is futile to try new medicines when initial trials have failed? No, a small number of patients with uncontrolled epilepsy (approximately 4% per year) achieve a 6-month or greater seizure remission with ongoing medical trials. Furthermore, additional patients will have their seizure control improved, so we should not “give up” on medical treatments. However, the low chance for seizure freedom when initial anticonvulsant trials have not been effective should serve as a “red flag,” indicating that a patient is unlikely to gain seizure control except through seizure surgery.

CAUTION!

CAUTION!What constitutes “seizure control”? Is it ok if my patient still has some seizures?

For the most part, even occasional seizures are associated with significant risks and a profound impact on quality of life. In the USA, this negative effect is best illustrated by driving. Patients experiencing just a few “breakthrough” seizures each year are not allowed to drive. Except for people living in certain metropolitan areas, this loss may limit employment, educational, and social opportunities. In fact, the lives of people with “nearly complete” seizure control often resemble those of people with poor control more closely than those of people with complete control.

Nevertheless, seizures vary widely in physical manifestations and predictability, and these factors can mitigate the impact of seizures on a patient’s life. For example, focal seizures that do not result in a loss of consciousness or motor control don’t expose the person to a risk for accidents, and they usually don’t interfere with driving or working. Most patients and their physicians don’t consider surgery in this circumstance. An intermediate situation would be seizures occurring exclusively during sleep. The predictability allows patients to go about their daily activities (including working and driving) without fear of having a seizure. However, the ongoing nocturnal seizures still pose significant physical risks. While patients may not feel that the seizures are impacting their lives, they must be reminded that surgery can reduce the morbidity and mortality related to the ongoing seizures. Finally, seizures with prolonged premonitory symptoms may allow patients to get to safety, preventing accidents and injuries. When the pattern is consistent, people are sometimes allowed to drive. Although prolonged auras may lessen the impact of seizures, they don’t stop seizures from occurring during important daily activities. Thus, they should rarely be a consideration in whether to refer a patient for surgery.

Should my patient be referred for seizure surgery now? A bottom line

Over a decade has passed since a randomized trial of anterior temporal lobectomy (the most common resective surgery) highlighted the dramatically enhanced chance of seizure freedom in patients who undergo surgery over those those relying on medication alone. More recent studies suggest that successful epilepsy surgery results in prolonged life span, improved quality of life, and lower medical costs. Surprisingly, these findings have not led to increased utilization of seizure surgery. The reasons are not clear. Societal and healthcare system issues appear to play a role; patients are increasingly managed in regional centers (with lower surgical volumes and higher complication rates) rather than referral centers focused on surgical management. Also, surgery is less likely to be performed for ethnic minorities and those with Medicaid insurance, suggesting that economic barriers to surgery play a role.

While societal constraints and healthcare system issues contribute to surgical underutilization, physician and patient perceptions also affect the use of seizure surgery. Despite overwhelming evidence of surgical efficacy and strong recommendations from professional societies, many neurologists do not refer patients for epilepsy surgery. In response to the concern that many good candidates for surgery are not being referred, a panel of experts developed an online tool for identifying candidates for seizure surgery. This panel of epileptologists, neurosurgeons, and general neurologists reviewed thousands of clinical scenarios, reaching general agreement about surgical candidacy for patients who had tried appropriate medicines with incomplete control of disabling seizures.

TIPS AND TRICKS

TIPS AND TRICKSHow will my patient be evaluated?

Video–EEG monitoring remains the cornerstone of the presurgical evaluation, serving several purposes. First, it eliminates the possibility that medication trials failed due to “mistaken identity.” Seizure mimics such as syncope, parasomnias, and psychogenic nonepileptic events are a common finding on the epilepsy monitoring unit. They sometimes surprise us, especially in patients with coexistent well-controlled epilepsy. Second, video–EEG monitoring determines whether seizures begin from a single focus, from multiple foci, or diffusely. Often, prior evaluations have hinted at this outcome, but recordings obtained during the seizures are the “gold standard” for defining seizure physiology. Third, the recordings may be sufficient to localize the seizure onset zone, helping to define a “target” for resective surgery.

Referring physicians should ensure that prior studies are included with the referral packet, as these anatomic (MRI) and physiologic (EEG) data help to guide the video–EEG evaluation. For example, patients with a focal lesion on MRI may not need extensive video–EEG recording to “prove” that their seizures arise near the lesion. Conversely, a patient with an EEG showing independent spike discharges from the left and right temporal lobe may require more extensive monitoring before one can be confident that resection of a single focus will be of benefit.

Over the last two decades, high-resolution anatomic imaging with MRI has become a mainstay of the presurgical evaluation for patients who are candidates to undergo resection of the seizure focus. Even when a patient’s initial MRI obtained at the time of diagnosis fails to reveal an abnormality, high-resolution scans often demonstrate subtle localizing abnormalities such as mesial temporal sclerosis or focal cortical dysplasia. In addition to refining the seizure localization, MRI often indicates the underlying pathology, hence the prognosis for complete seizure control after surgery.

When MRI fails to demonstrate a structural “target,” nuclear medicine studies such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) may provide localizing information to confirm or refine the video–EEG localization. Both are low-resolution, functional studies that provide little anatomic information. SPECT measures blood flow at the time of injection (typically increased during a seizure) and thus is most useful when the radioisotope is injected at the onset of the seizure. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose is the most commonly used PET tracer; it measures glucose uptake indicating tissue metabolism, which is typically reduced in the seizure focus (except during seizures), so PET should not be performed in the peri-ictal period. Functional and anatomic studies can be combined by co-registering (superimposing) MRI scans and physiological studies including EEG, magnetoencephalogram (MEG), or nuclear medicine studies. The combined information draws on the advantages of both modalities and can be especially useful in mapping out a surgical plan, especially in complex cases.

Neuropsychological studies remain critical in formulating a surgical plan. The Wada (intracarotid amobarbital) test is the conventional test for lateralizing language function. Many centers now use functional MRI for this purpose, and further evolution towards noninvasive studies seems likely. A full cognitive battery is administered before surgery and repeated at a defined time (usually a year) after surgery. This ensures that patients who undergo surgery can be counseled on subtle new deficits whether or not they recognize a problem.

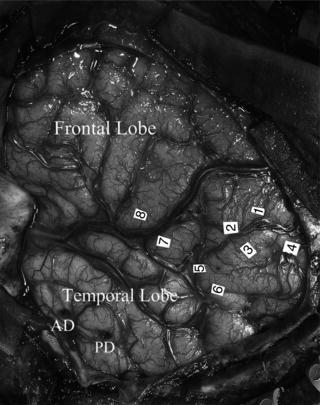

Precise seizure focus localization and implementation of the final surgical plan requires the best possible EEG recordings. Sometimes this information can be obtained only by directly evaluating cortical tissue. Cortical EEG recording, known as electrocorticography (ECoG), is used to hone the surgical plan. ECoG can be performed during the operation or extraoperatively over the course of days to weeks. Following characterization of the seizure focus, the final surgical plan is implemented, balancing the need for eliminating seizure-producing tissue with the risk for affecting functional tissue identified by classical anatomy, electrical stimulation mapping, or both (Figure 27.1).

What are the surgical options and expected outcomes?

Resective surgery

When seizures can’t be controlled with medicine, excision of seizure-producing tissue provides the best chance for gaining seizure control. These excisions range from simple removal of a focal lesion such as cavernous malformation to removal of all cerebral cortex of the hemisphere such as that performed during an anatomic hemispherectomy in patients with Rasmussen’s syndrome. Despite considerable variation in technique and patient population, surgical series have consistently shown that most patients undergoing focal resections benefit from surgery. The prognosis for complete seizure control is largely based on the underlying pathology; patients with discrete lesions such as cavernous malformations or hippocampal sclerosis have an 80–90% chance that their seizures will be completely controlled 2 years after surgery. Patients with more diffuse pathologies such as cortical dysplasia are less likely to gain complete control. Nevertheless, experienced centers have developed strategies that provide complete seizure control for most patients undergoing surgery for cortical dysplasia. As expected, long-term outcomes reported using life table analyses are less favorable than those in which only the prior year or two are considered. Taken together, long-term follow-up studies indicate that roughly half of all patients who undergo an anterior temporal lobectomy stop having seizures altogether, while many others experience many seizure-free years after surgery, even if they have occasional relapses.

Figure 27.1. Intraoperative photograph showing a left hemispheric functional map in a young man with nonlesional temporal lobe epilepsy. Electrical stimulation mapping revealed sensory or motor responses at sites 1–4 and speech arrests at sites 5–8. ECoG revealed continuous epileptiform activity from anterior (AD) and posterior (PD) depth electrodes inserted through the middle temporal gyrus into the amygdala and hippocampus, respectively. Documentation of a medial temporal seizure focus along with a lack of anterior temporal language sites allowed for a successful, tailored anterior-medial temporal resection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree