When to Do Ventral versus Dorsal Decompression and Fusion in the Cervical Spine for Trauma

Conor Regan

Moe R. Lim

Trauma to the cervical spine can result in a large range of injury patterns. The decision to operate is primarily based on the morphology of the injury, integrity of the diskoligamentous complex, and the presence or absence of neurologic compromise. The recently described subaxial injury classification system (1) categorizes injuries into compressive, distractive, and translational or rotational injuries in increasing order of severity. The choice between ventral and/or dorsal approaches to optimize treatment remains controversial (2). The decision for approach depends largely on the injury pattern and on surgeon preference.

Ventral cervical decompression and fusion enjoys a long history of success. Sagittal plane deformity can be corrected by interbody structural grafting. Optimal canal decompression can be obtained by complete discectomies and corpectomies. The approach allows for dissection in intermuscular planes with minimal soft tissue dissection, resulting in less postoperative pain and a very low risk of infection. Single-level fusion rates with instrumentation are between 90% and 95% in most studies (3). The downsides specific to the anterior approach are also well documented and include the risk of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, dysphagia, dysphonia, esophageal injury, and decreased overall instrumentation construct strength when compared to posterior instrumentation (4).

Dorsal stabilization of the cervical spine has also been historically successful. Modern constructs with polyaxial lateral mass screws and pedicle screws have been shown in biomechanical studies to result in superior strength when compared to anterior fixation (5,6). The stabilization construct can be readily extended over multiple levels from the occiput to the thoracic spine as the injury dictates. Facet joint dislocations can also be directly reduced posteriorly. The posterior approach, however, involves a much higher degree of muscular dissection than the anterior approach, resulting in greater postoperative pain and higher rates of wound infection. Additionally, posterior instrumentation does not have the same capability to correct sagittal deformity that is inherent to ventral constructs with structural grafts.

Certain injuries lend themselves more to particular approaches. In choosing the optimal approach, injury morphology and subtypes should be considered as a large part of a treatment algorithm in concert with patient factors and surgeon comfort. Injury patterns are described in detail for the remainder of this chapter, with consideration given to optimal management of each fracture type.

ODONTOID FRACTURES

Odontoid fractures occur with high-energy trauma in the young and low-energy falls in the elderly (7). The treatment of type I apical injuries and type III fractures traversing the cancellous bone in the body of C2 are generally nonoperative. Type II fractures through the odontoid waist have a union rate of 66% with closed treatment in a halo (8). Type II fractures with initial displacement of greater than 5 mm, angulation greater than 10 degrees, dorsal displacement, or occurring in patients aged 50 or greater have high rates of nonunion and malunion. In these situations, strong consideration should be given to operative intervention (9,10). Type II fractures have been further subclassified by Grauer et al. (11) into IIA, IIB, and IIC fractures for treatment considerations. Type IIA fractures are nondisplaced and can be treated either with external immobilization in a halo or with surgery. Type IIB fractures have an oblique fracture line, extending from rostral to dorsal-caudal. This pattern is amenable to fixation with anterior screws. Type IIC fractures have a ventral-caudal to dorsal-rostral fracture line and are difficult to treat with an anterior screw. This pattern may be more optimally approached posteriorly.

Ventral fixation of type II odontoid fractures has the advantage of motion preservation at the C1-C2 segment. It

should be considered for younger patients with good bone stock. Ventral screw placement requires near-anatomic reduction and a transverse or ventral-rostral to dorsal-caudal fracture line (type IIB). Relative contraindications for anterior screw fixation include patients with a large chest wall, which blocks the angulation necessary to place an anterior screw; rupture of the transverse ligament with C1-C2 instability; and a significant amount of comminution at the odontoid waist, which would result in shortening with anterior instrumentation.

should be considered for younger patients with good bone stock. Ventral screw placement requires near-anatomic reduction and a transverse or ventral-rostral to dorsal-caudal fracture line (type IIB). Relative contraindications for anterior screw fixation include patients with a large chest wall, which blocks the angulation necessary to place an anterior screw; rupture of the transverse ligament with C1-C2 instability; and a significant amount of comminution at the odontoid waist, which would result in shortening with anterior instrumentation.

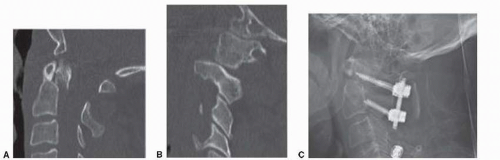

Dorsal fixation for odontoid fractures is useful for type IIC injuries since the fracture line is parallel to the optimal path of the anterior screw. There are several options for dorsal fixation including wiring of the C1-C2 dorsal elements, Magerl’s transarticular screws, or Harm’s technique with lateral mass screws (Fig. 145.1). All of these techniques have been shown to have high union rates. The most relevant downside of the dorsal C1-C2 fusion is the loss of rotational range of motion in the cervical spine. Fusion of C1-C2 eliminates approximately 50% of rotation compared to the intact spine.

Wiring of the C1-C2 dorsal elements has a very high rate of fusion, but requires an intact dorsal arch of C1 and postoperative halo immobilization (12). Magerl’s transarticular C1-C2 screws also have a high union rate. However, screw insertion places the vertebral arteries at significant risk as they exit the C2 transverse foramen and pose a technical challenge. There must also be near-anatomic reduction of the C1-C2 facets in order to allow optimal screw placement (13). Harm’s technique with C1 lateral mass screw and C2 isthmus/pedicle screw constructs result in high fusion rates, produce excellent biomechanical stability, and can be performed with less danger to the vertebral arteries. This construct can be extended to include the occiput or the subaxial spine as needed for stability. The approach also allows for open reduction of C1-C2 in cases of subluxation. This technique does, however, require intact C1 lateral masses to obtain fixation. In patients with small dysplastic C2 pars, fixation into C2 can be achieved via laminar screws (14).

BURST FRACTURES AND FLEXION-COMPRESSION (TEARDROP) FRACTURES

Cervical burst fractures occur via a primarily axial load with subsequent compressive failure of the vertebral body and bony retropulsion into the spinal canal. The fracture pattern is similar to burst fractures of the thoracolumbar spine. In contrast, compression-flexion teardrop fractures occur via an axial load with a concomitant flexion force. There exists a spectrum of severity with flexion-compression teardrop injuries as described by Allen et al. (15). As energy increases, the ventral caudal aspect of the superior vertebra shears off a triangular bony fragment (the teardrop fragment) while the posterior ligamentous structures fail under tensile stress, thereby creating a highly unstable spinal segment. As the force increases, retrolisthesis of the remaining vertebral body occurs with resultant spinal cord compression. Burst and teardrop fractures can be treated by an anterior, posterior, or combined anterior/posterior approaches. The choice of approach depends primarily on the degree of injury to the diskoligamentous complex.

Corpectomy and fusion has several advantages. It allows for optimal decompression of the spinal canal and low wound complication rates. It also provides the opportunity to correct sagittal plane deformity via structural grafting. Biomechanical studies have shown that anterior instrumentation constructs alone may have sufficient stability as they are at least as stiff as the intact spine even in cases of complete diskoligamentous disruption (16). These findings, however, are not as compelling in osteopenic bone (17). Ventral instrumentation, however, is not as stable in rotational and bending loads compared to posterior or combined ventral/dorsal constructs. Additionally, with an anterior-only approach, facet joint reduction is necessarily indirect and may be challenging.

In contrast, a dorsal approach allows for reliable anatomic reduction of the facet joints and results in powerful

constructs with greatly increased stiffness compared to the intact spine. There is a decreased ability to control kyphotic deformity with dorsal-only instrumentation, but a small degree of segmental kyphosis usually has little clinical significance for most patients. In patients with underlying congenital or acquired cervical stenosis, however, the resulting kyphotic deformity may cause unacceptable neurologic compromise. Dorsal approaches result in high fusion rates but do have higher wound complication rates. The most important limitation of the dorsal approach is the inability to directly decompress spinal cord by removal of traumatic disk herniations and/or impinging retrolisthesed bone fragments.

constructs with greatly increased stiffness compared to the intact spine. There is a decreased ability to control kyphotic deformity with dorsal-only instrumentation, but a small degree of segmental kyphosis usually has little clinical significance for most patients. In patients with underlying congenital or acquired cervical stenosis, however, the resulting kyphotic deformity may cause unacceptable neurologic compromise. Dorsal approaches result in high fusion rates but do have higher wound complication rates. The most important limitation of the dorsal approach is the inability to directly decompress spinal cord by removal of traumatic disk herniations and/or impinging retrolisthesed bone fragments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree