1

Neurologic History & Examination

A thorough but directed history and neurologic examination are the keys to neurologic diagnosis and treatment. Laboratory studies, discussed in Chapter 2, can provide valuable additional information, but cannot replace the history and exam.

HISTORY

Taking a history from a patient with a neurologic complaint is fundamentally the same as taking any history.

Age

The patient’s age can be a major clue to the likely causes of a neurologic problem. For example, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and Huntington disease usually have their onset by middle age, whereas Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, brain tumors, and stroke predominantly affect older individuals.

Chief Complaint

The patient’s problem (chief complaint) should be defined as clearly as possible, because it will guide subsequent evaluation toward—or away from—the correct diagnosis. In eliciting the chief complaint, the goal is to describe the nature of the problem in a word or phrase.

Common neurologic complaints include confusion, dizziness, weakness, shaking, numbness, blurred vision, and spells. Each of these terms means different things to different people, so it is critical to point evaluation of the problem in the right direction by getting as much clarification as possible regarding what the patient is trying to convey.

A. Confusion

Confusion reported by the patient or family members may include memory impairment, getting lost, difficulty understanding or producing spoken or written language, problems with numbers, faulty judgment, personality change, or combinations thereof. Symptoms of confusion may be difficult to characterize, and asking for specific examples can be helpful in this regard.

B. Dizziness

Dizziness can mean vertigo (the illusion of movement of oneself or the environment), imbalance (unsteadiness due to extrapyramidal, vestibular, cerebellar, or sensory deficits), or presyncope (light-headedness resulting from cerebral hypoperfusion).

C. Weakness

Weakness is the term neurologists use to mean loss of power from disorders affecting motor pathways in the central or peripheral nervous system or skeletal muscle. However, patients sometimes use this term when they mean generalized fatigue, lethargy, or even sensory disturbances.

D. Shaking

Shaking may represent abnormal movements such as tremor, chorea, athetosis, myoclonus, or fasciculation (see Chapter 11, Movement Disorders), but the patient is unlikely to classify his or her problem according to this terminology. Correct classification depends on observing the movements in question or, if they are intermittent and not present when the history is taken, asking the patient to demonstrate them.

E. Numbness

Numbness can refer to any of a variety of sensory disturbances, including hypesthesia (decreased sensitivity), hyperesthesia (increased sensitivity), or paresthesia (“pins and needles” sensation). Patients occasionally also use this term to signify weakness.

F. Blurred vision

Blurred vision may represent diplopia (double vision), ocular oscillations, reduced visual acuity, or visual field cuts.

G. Spells

Spells imply episodic and often recurrent symptoms such as may be seen with epilepsy or syncope (fainting).

History of Present Illness

The history of present illness should provide a detailed description of the chief complaint, including the following features.

A. Quality of Symptoms

Some symptoms, such as pain, may have distinctive features that are diagnostically helpful. Neuropathic pain—which results from direct injury to nerves—may be described as especially unpleasant (dysesthetic) and may be accompanied by increased sensitivity to pain (hyperalgesia) or touch (hyperesthesia), or by the perception of a normally innocuous stimulus as painful (allodynia), in the affected area. The quality of symptoms includes their severity—although individual thresholds for seeking medical attention for a symptom vary, it is often useful to ask a patient to rank the present complaint in relation to problems he or she has had in the past.

B. Location of Symptoms

The location of symptoms is critical to neurologic diagnosis, and patients should be encouraged to localize their symptoms as precisely as possible. The spatial distribution of weakness, decreased sensation, or pain helps to assign the underlying disease process to a specific site in the nervous system. This provides an anatomic diagnosis, which is then refined to identify the cause.

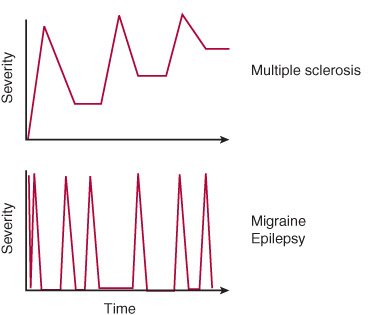

C. Time Course

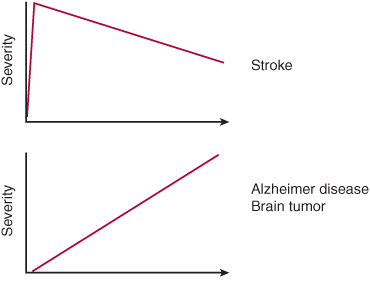

It is important to determine when the problem began, whether it came on abruptly or insidiously, and if its subsequent course has been characterized by improvement, worsening, or exacerbation and remission (Figure 1-1). For episodic disorders, such as headache or seizures, the time course of individual episodes should also be determined.

Figure 1-1. Temporal patterns of neurologic disease and examples of each.

D. Precipitating, Exacerbating, and Alleviating Factors

Some symptoms may appear to be spontaneous, but in other cases, specific precipitating factors can be identified. Through observation and experimentation, patients often become aware of factors that worsen symptoms, and which they can avoid, or factors that prevent symptoms or provide relief.

E. Associated Symptoms

Associated symptoms can assist with anatomic or etiologic diagnosis. For example, neck pain accompanying leg weakness suggests a cervical myelopathy (spinal cord disorder), and fever in the setting of headache raises concern about meningitis.

Past Medical History

Certain aspects of the past medical history may be especially relevant to a neurologic complaint.

A. Illnesses

Many preexisting illnesses can predispose to neurologic disease, including hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease.

B. Operations

Open heart surgery may be complicated by stroke or a confusional state. Entrapment neuropathies (disorders of a peripheral nerve due to local pressure) affecting the upper or lower extremity may complicate the perioperative course.

C. Obstetrical History

Pregnancy can worsen epilepsy, at least partly due to altered metabolism of anticonvulsant drugs. The frequency of migraine attacks may increase or decrease. Pregnancy is a predisposing condition for benign intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri) and entrapment neuropathies, especially carpal tunnel syndrome (median neuropathy) and meralgia paresthetica (lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy). Traumatic neuropathies affecting the obturator, femoral, or peroneal nerve may result from pressure exerted by the fetal head or obstetrical forceps during delivery. Eclampsia is a life-threatening syndrome in which generalized tonic-clonic seizures complicate the course of pre-eclampsia (hypertension with proteinuria) during pregnancy.

D. Medications

A wide range of medications can cause adverse neurologic effects, including confusional states or coma, headache, ataxia, neuromuscular disorders, neuropathy, and seizures.

E. Immunizations

Vaccination can prevent several neurologic diseases, including poliomyelitis, diphtheria, tetanus, rabies, and meningococcal meningitis. Vaccinations may be associated with postvaccination autoimmune encephalitis, myelitis, or neuritis (inflammation of the brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves).

F. Diet

Dietary deficiency and excess can both lead to neurologic disease. Deficiency of vitamin B1 (thiamin) is responsible for the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and polyneuropathy in alcoholics. Vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency causes pellagra, which is characterized by dementia. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency usually results from malabsorption associated with pernicious anemia and produces combined systems disease (degeneration of corticospinal tracts and posterior columns in the spinal cord) and dementia (megaloblastic madness). Inadequate intake of vitamin E (tocopherol) can also lead to spinal cord degeneration. Conversely, hypervitaminosis A can produce intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri) with headache, visual deficits, and seizures, whereas excessive intake of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) is a cause of polyneuropathy. Excessive consumption of fats is a risk factor for stroke. Finally, ingestion of improperly preserved foods containing botulinum toxin causes botulism, a disorder of acetylcholine release at autonomic and neuromuscular synapses, which presents with descending paralysis.

G. Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drug Use

Tobacco use is associated with lung cancer, which may metastasize to the central nervous system or produce paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes. Alcohol abuse can produce withdrawal seizures, polyneuropathy, and nutritional disorders of the nervous system. Use of intravenous drugs may suggest HIV disease or drug-related neurologic complications of infection or vasculitis.

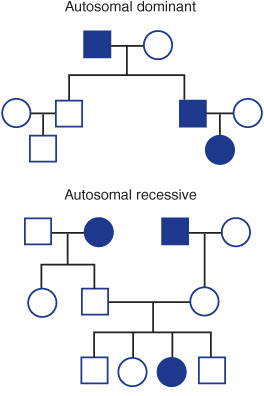

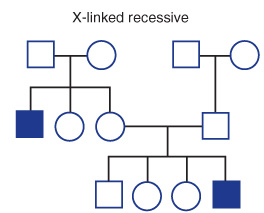

Family History

This should indicate any past or current diseases in the spouse and first- (parents, siblings, children) and second-(grandparents, grandchildren) degree relatives. Several neurologic diseases are inherited in Mendelian or more complex patterns, such as Huntington disease (autosomal dominant), Wilson disease (autosomal recessive), and Duchenne muscular dystrophy (X-linked recessive) (Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2. Simple Mendelian patterns of inheritance. Squares represent males, circles females, and filled symbols affected individuals.

Social History

Information about the patient’s education and occupation help in the interpretation of whether his or her cognitive performance is background-appropriate. The sexual history may indicate risk for sexually transmitted diseases that affect the nervous system, such as syphilis or HIV disease. The travel history can document possible exposure to infections endemic to particular geographic areas.

Review of Systems

Non-neurologic complaints elicited in the review of systems may point to a systemic cause of a neurologic problem.

1. General—Weight loss or fever may indicate a neoplastic or infectious cause of neurologic symptoms.

2. Immune—Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) may lead to dementia, myelopathy, neuropathy, myopathy, or infections (eg, toxoplasmosis) or tumors (eg, lymphoma) affecting the nervous system.

3. Hematologic—Polycythemia and thrombocytosis may predispose to ischemic stroke, whereas thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy are associated with intracranial hemorrhage.

4. Endocrine—Diabetes increases the risk for stroke and may be complicated by polyneuropathy. Hypothyroidism may lead to coma, dementia, or ataxia.

5. Skin—Characteristic skin lesions are seen in certain disorders that also affect the nervous system, such as neurofibromatosis and postherpetic neuralgia.

6. Eyes, ears, nose, and throat—Neck stiffness is a common feature of meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

7. Cardiovascular—Ischemic or valvular heart disease and hypertension are major risk factors for stroke.

8. Respiratory—Cough, hemoptysis, or night sweats may be manifestations of tuberculosis or lung neoplasm, which can disseminate to affect the nervous system.

9. Gastrointestinal—Hematemesis, jaundice, and diarrhea may direct the investigation of a confusional state toward hepatic encephalopathy.

10. Genitourinary—Urinary retention or incontinence, or impotence, may be manifestations of peripheral neuropathy or myelopathy.

11. Musculoskeletal—Muscle pain and tenderness may accompany the myopathy of polymyositis.

12. Psychiatric—Psychosis, depression, and mania may be manifestations of a neurologic disease.

Summary

Upon completion of the history, the examiner should have a clear understanding of the chief complaint, including its location and time course, and familiarity with elements of the past medical history, family and social history, and review of systems that may be related to the complaint. This information should help to guide the general physical and neurologic examinations, which should focus on areas suggested by the history. For example, in an elderly patient who presents with the sudden onset of hemiparesis and hemisensory loss, which is likely to be due to stroke, the general physical examination should stress the cardiovascular system, because a variety of cardiovascular disorders predispose to stroke. On the other hand, if a patient complains of pain and numbness in the hand, much of the exam should be devoted to examining sensation, strength, and reflexes in the affected upper extremity.

GENERAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

In a patient with a neurologic complaint, the general physical examination should focus on looking for abnormalities often associated with neurologic problems.

Vital Signs

A. Blood Pressure

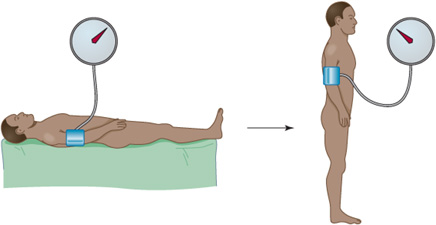

Elevated blood pressure may indicate chronic hypertension, which is a risk factor for stroke and is also seen acutely in the setting of hypertensive encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, or intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Blood pressure that drops by ≥20 mm Hg (systolic) or ≥10 mm Hg (diastolic) when a patient switches from recumbent to upright signifies orthostatic hypotension (Figure 1-3). If the drop in blood pressure is accompanied by a compensatory increase in pulse rate, sympathetic autonomic reflexes are intact, and the likely cause is hypovolemia. However, the absence of a compensatory response is consistent with central (eg, Parkinson disease) or peripheral (eg, polyneuropathy) disorders of sympathetic function or an adverse effect of sympatholytic (eg, antihypertensive) drugs.

Figure 1-3. Test for orthostatic hypotension. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate are measured with the patent recumbent (left) and then each minute after standing for 5 min (right). A decrease in systolic blood pressure of ≥20 mm or in diastolic blood pressure of ≥10 mm indicates orthostatic hypotension. When autonomic function is normal, as in hypovolemia, there is a compensatory increase in heart rate, whereas lack of such an increase suggests autonomic failure.

B. Pulse

A rapid or irregular pulse—especially the irregularly irregular pulse of atrial fibrillation—may point to a cardiac arrhythmia as the cause of stroke or syncope.

C. Respiratory Rate

The respiratory rate may provide a clue to the cause of a metabolic disturbance associated with coma or a confusional state. Rapid respiration (tachypnea) can be seen in hepatic encephalopathy, pulmonary disorders, sepsis, or salicylate intoxication; depressed respiration is observed with pulmonary disorders and sedative drug intoxication. Tachypnea may also be a manifestation of neuromuscular disease affecting the diaphragm. Abnormal respiratory patterns are also observed in coma: Cheyne-Stokes breathing (alternating deep breaths, or hyperpnea, and apnea) can occur in metabolic disorders or with hemispheric lesions, whereas apneustic, cluster, or ataxic breathing (see Chapter 3, Coma) implies a brainstem disorder.

D. Temperature

Fever (hyperthermia) occurs with infection of the meninges (meningitis), brain (encephalitis), or spinal cord (myelitis). Hypothermia can be seen in ethanol or sedative drug intoxication, hypoglycemia, hepatic encephalopathy, Wernicke encephalopathy, and hypothyroidism.

Skin

Jaundice (icterus) suggests liver disease as the cause of a confusional state or movement disorder. Coarse dry skin, dry brittle hair, and subcutaneous edema are characteristic of hypothyroidism. Petechiae are seen in meningococcal meningitis, and petechiae or ecchymoses may suggest a coagulopathy as the cause of subdural, intracerebral, or paraspinal hemorrhage. Bacterial endocarditis, a cause of stroke, can produce a variety of cutaneous lesions, including splinter (subungual) hemorrhages, Osler nodes (painful swellings on the distal fingers), and Janeway lesions (painless hemorrhages on the palms and soles). Hot dry skin accompanies anticholinergic drug intoxication.

Head, Eyes, Ears, & Neck

A. Head

Examination of the head may reveal signs of trauma, such as scalp lacerations or contusions. Basal skull fracture may produce postauricular hematoma (Battle sign), periorbital hematoma (raccoon eyes), hemotympanum, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhea or rhinorrhea (Figure 1-4). Percussion of the skull over a subdural hematoma may cause pain. A vascular bruit heard on auscultation of the skull is associated with arteriovenous malformations.

Figure 1-4. Signs of head trauma include periorbital (raccoon eyes, A) or postauricular (Battle sign, B) hematoma, each of which suggests basal skull fracture. (From Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, et al. The Atlas of Emergency Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010.)

B. Eyes

Icteric sclerae are seen in liver disease. Pigmented (Kayser-Fleischer) corneal rings—best seen by slit-lamp examination—are produced by deposition of copper in Wilson disease. Retinal hemorrhages (Roth spots) may occur in bacterial endocarditis, which is also associated with septic emboli that may produce stroke. Exophthalmos is observed with hyperthyroidism, orbital or retro-orbital masses, and cavernous sinus thrombosis.

C. Ears

Otoscopic examination shows bulging, opacity, and erythema of the tympanic membrane in otitis media, which may spread to produce bacterial meningitis.

D. Neck

Meningeal signs (Figure 1-5), such as neck stiffness on passive flexion or thigh flexion upon flexion of the neck (Brudzinski sign), are seen in meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Restricted lateral movement (lateral flexion or rotation) of the neck may accompany cervical spondylosis. Auscultation of the neck may reveal a carotid bruit consistent with predisposition to stroke.

Figure 1-5. Signs of meningeal irritation. Kernig sign (A) is resistance to passive extension at the knee with the hip flexed. Brudzinski sign (B) is flexion at the hip and knee in response to passive flexion of the neck. (From LeBlond RF, DeGowin RL, Brown DD. DeGowin’s Diagnostic Examination. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.)

Chest & Cardiovascular

Signs of respiratory muscle weakness—such as intercostal muscle retraction and the use of accessory muscles—may occur in neuromuscular disorders. Heart murmurs may be associated with valvular heart disease predisposing to stroke and with infective endocarditis and its neurologic sequelae.

Abdomen

Abdominal examination may reveal a source of systemic infection or suggest liver disease and is always important in patients with the new onset of back pain, because a variety of pathologic intra-abdominal processes (eg, pancreatic carcinoma or aortic aneurysm) may produce pain that radiates to the back.

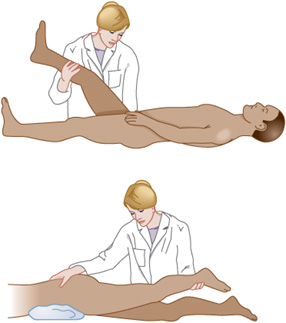

Extremities & Back

Resistance to passive extension of the knee with the hip flexed (Kernig sign) is seen in meningitis. Raising the extended leg with the patient supine (straight leg raising, or Lasègue sign) stretches the L4-S2 roots and sciatic nerve, whereas raising the extended leg with the patient prone (reverse straight leg raising) stretches the L2-L4 roots and femoral nerve and may reproduce radicular pain in patients with lesions affecting these structures (Figure 1-6). Localized pain with percussion of the spine may be a sign of vertebral or epidural infection. Auscultation of the spine may reveal a bruit due to spinal vascular malformation.

Figure 1-6. Signs of lumbosacral nerve root irritation. The straight leg raising or Lasègue sign (top) is pain in an L4-S2 root or sciatic nerve distribution in response to raising the extended leg with the patient supine. The reverse straight leg raising sign (bottom) is pain in an L2-L4 root or femoral nerve distribution in response to raising the extended leg with the patient prone. (From LeBlond RF, DeGowin RL, Brown DD. DeGowin’s Diagnostic Examination. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2009.)

Rectal & Pelvic

Rectal examination can provide evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, which is a common precipitant of hepatic encephalopathy. Rectal or pelvic examination may disclose a mass lesion responsible for pain referred to the back.

NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION

The neurologic examination should be tailored to each patient’s specific complaint. Each area of the exam—mental status, cranial nerves, motor function, sensory function, coordination, reflexes, and stance and gait—should always be covered, but the relative emphasis among and within areas will differ. The patient’s history should have raised questions that the examination can now address. For example, if the patient’s complaint is weakness, the examiner seeks to determine its distribution and severity and whether it is accompanied by deficits in other areas, such as sensation and reflexes. The goal is to obtain the information necessary to generate an anatomic diagnosis on completion of the examination.

Mental Status Examination

The mental status examination addresses two key questions: (1) Is level of consciousness (wakefulness or alertness) normal or abnormal? (2) If the level of consciousness permits more detailed examination, is cognitive function normal, and if not, what is the nature and extent of the abnormality?

A. Level of Consciousness

Consciousness is awareness of the internal or external world, and the level of consciousness is described in terms of the patient’s apparent state of wakefulness and response to stimuli. A patient with a normal level of consciousness is awake (or can be awakened), alert (responds appropriately to visual or verbal cues), and oriented (knows who and where he or she is and the approximate date or time).

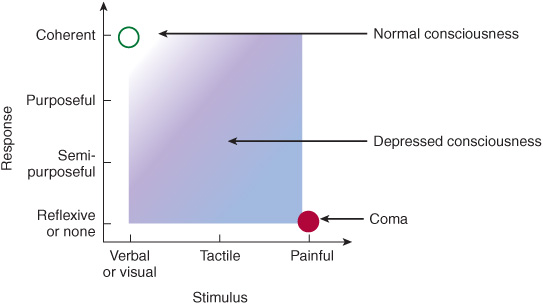

Abnormal (depressed) consciousness represents a continuum ranging from mild sleepiness to unarousable unresponsiveness (coma, see Chapter 3). Depressed consciousness short of coma is sometimes referred to as a confusional state, delirium, or stupor, but should be characterized more precisely in terms of the stimulus–response patterns observed. Progressively more severe impairment of consciousness requires stimuli of increasing intensity to elicit increasingly primitive (nonpurposeful or reflexive) responses (Figure 1-7).

Figure 1-7. Assessment of level of consciousness in relation to the patient’s response to stimulation. A normally conscious patient responds coherently to visual or verbal stimulation, whereas a patient with impaired consciousness requires increasingly intense stimulation and exhibits increasingly primitive responses.

B. Cognitive Function

Cognitive function involves many spheres of activity, some of which are localized and others dispersed throughout the cerebral hemispheres. The strategy in examining cognitive function is to assess a range of specific functions and, if abnormalities are found, to evaluate whether these can be attributed to a specific brain region or require more widespread involvement of the brain. For example, discrete disorders of language (aphasia) and memory (amnesia) can often be assigned to a circumscribed area of the brain, whereas more global deterioration of cognitive function, as seen in dementia, implies diffuse or multifocal disease.

1. Bifrontal or diffuse functions—Attention is the ability to focus on a particular sensory stimulus to the exclusion of others; concentration is sustained attention. Attention can be tested by asking the patient to immediately repeat a series of digits (a normal person can repeat five to seven digits correctly), and concentration can be tested by having the patient count backward from 100 by 7. Abstract thought processes like insight and judgment can be assessed by asking the patient to list similarities and differences between objects (eg, an apple and an orange), interpret proverbs (overly concrete interpretations suggest impaired abstraction ability), or describe what he or she would do in a hypothetical situation requiring judgment (eg, finding an addressed envelope on the street). Fund of knowledge can be tested by asking for information that a normal person of the patient’s age and cultural background would be expected to possess (eg, the name of the President, sports stars, or other celebrities, or of major events in the news). This is not intended as a test of intelligence, but to determine whether the patient has been incorporating new information normally in the recent past. Affect is the external behavioral correlate of the patient’s (internal) mood and may be manifested by talkativeness or lack thereof, facial expression, and posture. Conversation with the patient may also reveal abnormalities of thought content, such as delusions or hallucinations, which are usually associated with psychiatric disease, but can also exist in confusional states (eg, alcohol withdrawal) or complex partial seizures.

2. Memory—Memory is the ability to register, store, and retrieve information and can be impaired by either diffuse cortical or bilateral temporal lobe disease. Memory is assessed clinically by testing immediate recall, recent memory, and remote memory, which correspond roughly to registration, storage, and retrieval, respectively. Tests of immediate recall are similar to tests of attention (see earlier discussion) and include having the patient immediately repeat a list of numbers or objects. To test recent memory, the patient can be asked to repeat the same list 3 to 5 minutes later. Remote memory

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree