Schizophrenia

Social and psychosocial factors

Current aetiological hypotheses about schizophrenia

Discussing schizophrenia with patients and their carers

Introduction

Of all the major psychiatric syndromes, schizophrenia is the most difficult to define and describe. This partly reflects the fact that, over the past 100 years, widely divergent concepts have been held in different countries and by different psychiatrists. Although there is now a greater consensus, substantial uncertainties remain. Indeed, schizophrenia remains the best example of the fundamental issues with which psychiatry continues to grapple—concepts of disease, classification, and aetiology. Having noted the complexities, we start with an introduction to acute schizophrenia and chronic schizophrenia. The reader should bear in mind that these will be idealized descriptions and comparisons, but it is useful to oversimplify at first before introducing the controversial issues.

Table 11.1 Common symptoms of acute schizophrenia

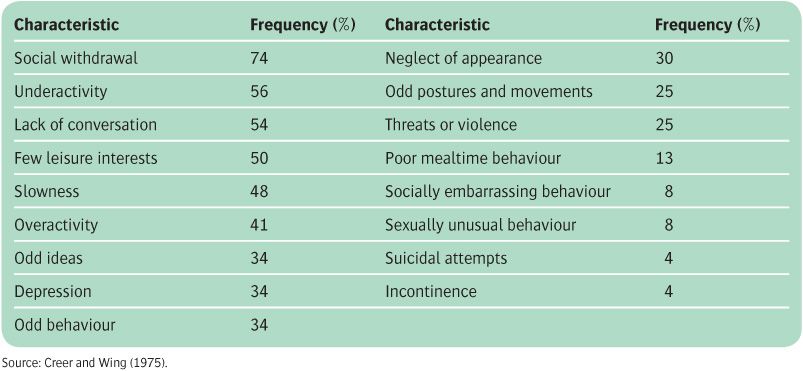

The predominant clinical features in acute schizophrenia are delusions, hallucinations, and interference with the flow of thoughts (see Table 11.1). These features are often called positive symptoms, and include specific symptoms known as first-rank symptoms, which are given particular weight in the diagnosis. Subtypes of schizophrenia are recognized based upon the relative prominence of the symptoms. Many patients recover from the acute illness, but progression to the chronic syndrome is also common. Its main features are very different, consisting of apathy, lack of drive, slowness, and social withdrawal (see Table 11.2). These features are often called negative symptoms. Once the chronic syndrome is established, few patients recover completely. In both phases of the disorder there may also be cognitive and affective symptoms and other features, as described later. For a review, see Arango and Carpenter (2011).

Table 11.2 Features of chronic schizophrenia

Clinical features

In this section, it is assumed that the reader has read the descriptions of symptoms and signs in Chapters 1 and 3, which include definitions of many of the cardinal features of schizophrenia.

The acute syndrome

The vignette in Box 11.1 illustrates several common features of acute schizophrenia, including prominent persecutory delusions, with accompanying hallucinations, gradual social withdrawal and impaired performance at work, and the odd idea that other people can read one’s thoughts.

In appearance and behaviour some patients with acute schizophrenia are entirely normal. Others seem changed, although not always in a way that would immediately point to psychosis. They may be preoccupied with their health, their appearance, religion, or other intense interests. Social withdrawal may occur—for example, spending a long time in their room, perhaps lying immobile on the bed. Some patients smile or laugh without obvious reason. Some appear to be constantly perplexed, while others are restless and noisy, or show sudden and unexpected variability of behaviour.

The speech often reflects an underlying thought disorder. In the early stages, there is vagueness in the patient’s talk that makes it difficult to grasp their meaning. Some patients have difficulty in dealing with abstract ideas. Other patients become preoccupied with vague pseudo-scientific or mystical ideas. When the thought disorder is more severe, two characteristic kinds of abnormality may occur. Disorders of the form (or stream) of thought include pressure of thought, poverty of thought, thought blocking, and thought withdrawal; some of these constitute first-rank symptoms (see Table 11.3). Thought disorder is reflected in the loosening of association between expressed ideas, and may be detected in illogical thinking (e.g. ‘knight’s move’ thinking) or talking past the point (vorbeireden). In its severest form, the structure and coherence of thinking are lost, so that utterances are jumbled (word salad or verbigeration). Some patients use ordinary words or phrases in unusual ways (metonyms or paraphrases), and a few coin new words (neologisms).

Auditory hallucinations are among the most frequent symptoms. They may take the form of noises, music, single words, brief phrases, or whole conversations. They may be unobtrusive, or so severe as to cause great distress. Some voices seem to give commands to the patient. Some patients hear their own thoughts apparently spoken out loud either as they think them (Gedankenlautwerden) or immediately afterwards (echo de la pensée), and some voices discuss the patient in the third person or comment on his actions; these are first-rank symptoms (see Table 11.3). Visual hallucinations are less frequent, and usually occur together with other kinds of hallucination. Tactile, olfactory, gustatory, and somatic hallucinations are reported by some patients. They are often interpreted in a delusional way—for example, hallucinatory sensations in the lower abdomen are attributed to unwanted sexual interference by a persecutor.

Table 11.3 Schneider’s symptoms of the first rank

Delusions are characteristic. Primary delusions are infrequent and are difficult to identify with certainty. Delusions may originate against a background of so-called primary delusional mood (Wahnstimmung). Persecutory delusions are common, but are not specific to schizophrenia, as they also characterize delusional disorders (see Chapter 12). Less common, but of greater diagnostic value, are delusions of reference and of control, and delusions about the possession of thought. The latter are delusions that thoughts are being inserted into or withdrawn from one’s mind, or ‘broadcast’ to other people.

Insight is almost always impaired. Most patients do not accept that their experiences result from illness, but usually ascribe them to the malevolent actions of other people.

Orientation is usually normal, although this may be difficult to determine if there is florid thought disorder or if the patient is too preoccupied with their psychotic experience to attend to the interviewer’s questions.

Alterations in mood are common and are of three main kinds. First, there may be symptoms of anxiety, depression, irritability, or euphoria. These can be clinically significant, but if such features are sufficiently prominent and sustained, the possibility of schizoaffective disorder or other affective psychosis should be considered. Secondly, there may be blunting (or flattening) of affect—that is, sustained emotional indifference or diminution of emotional response. Thirdly, there may be incongruity of affect, in which the expressed mood is not in keeping with the situation or with the patient’s own feelings.

Finally, we emphasize the variability of the clinical picture. Few patients experience all of the symptoms introduced above (as illustrated by the percentage figures shown in Table 11.1), while others already have features of the ‘chronic’ syndrome at first presentation. Moreover, the overall pattern and duration of features are also taken into account before making a diagnosis. These issues, together with some additional clinical features, are discussed later in the chapter.

The chronic syndrome

Although the positive symptoms of the acute syndrome may persist, the chronic syndrome is characterized by the negative symptoms of underactivity, lack of drive, social withdrawal, and emotional apathy. The vignette in Box 11.2 illustrates several of the negative features of what is sometimes called a schizophrenic ‘defect state.’ The most striking feature is diminished volition—that is, a lack of drive and initiative. Left to himself, the patient may remain inactive for long periods, or may engage in aimless and repeated activity. He withdraws from social encounters, and his social behaviour may deteriorate in ways that embarrass other people. Self-care may be poor, and the style of dress and presentation may be careful but somewhat inappropriate. Some patients collect and hoard objects, so that their surroundings become cluttered and dirty. Others break social conventions by talking intimately to strangers or shouting obscenities in public.

Speech is often abnormal, showing evidence of thought disorder of the kinds found in the acute syndrome described above. Affect is generally blunted, but when emotion is shown, it is often incongruous or shallow. Hallucinations and delusions occur, but are by no means universal. They tend to be held with little emotional response. For example, the patient may be convinced that they are being persecuted but show neither fear nor anger.

Various disorders of movement occur, including stereotypies, mannerisms and other catatonic symptoms, and dyskinesias (see below). The latter are common, and are primarily but not entirely due to antipsychotic medication.

As with acute schizophrenia, the symptoms and signs of the chronic illness are variable. At any stage, positive symptoms may recur or become exacerbated; this may be in response to life events, or to discontinuation of medication.

Subtypes of schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is conventionally divided into several subtypes, based upon the predominant clinical features.

• Paranoid schizophrenia is the commonest form. It is characterized by persecutory delusions, often systematized, and by persecutory auditory hallucinations. Thought disorder and affective, catatonic, and negative symptoms are not prominent. Personality is relatively well preserved. It has a later age of onset and a better prognosis than the other subtypes.

• In hebephrenic schizophrenia, also called disorganized schizophrenia, thought disorder and affective symptoms are prominent. The mood is variable, with behaviour often appearing silly and unpredictable. Delusions and hallucinations are fleeting and not systematized. Mannerisms are common. Speech is rambling and incoherent, reflecting the thought disorder. Negative symptoms occur early, and contribute to a poor prognosis.

• In catatonic schizophrenia, the most striking features are motor symptoms, as noted on p. 16, and changes in activity that vary between excitement and stupor. At times the person may appear to be in a dream-like (oneiroid) state. Formerly common, catatonic schizophrenia is now very rare, at least in industrialized countries. Possible reasons for this include a change in the nature of the illness, improvements in treatment, or past misdiagnosis of organic syndromes with catatonic symptoms. It has also been argued that catatonia is a distinct syndrome (Fink et al., 2010).

• Simple schizophrenia is characterized by the insidious development of odd behaviour, social withdrawal, and declining performance at work. Delusions and hallucinations are not evident. Clear schizophrenic symptoms are absent, and there is always the possibility of an earlier acute episode having gone undetected. Given the limited utility of the category and its history of abuse—for example, in the detention of political dissidents in the former Soviet Union (‘sluggish schizophrenia’)—its use should be avoided.

• Undifferentiated schizophrenia is the term used for cases which do not fit readily into any of the above subtypes, or where there are equally prominent features of more than one of them.

Two other categories have been introduced more recently. Residual schizophrenia refers to a stage of chronic schizophrenia when, for at least a year, there have been persistent negative symptoms but no recurrence of positive symptoms. Deficit syndrome describes a subtype of schizophrenia with early, severe, and persistent negative symptoms, and with some other differences in symptomatology and antecedents (Kirkpatrick et al., 2001).

These various subtypes are primarily descriptive, rather than delineating valid sub-syndromes. Other sub-classifications of schizophrenia have been proposed, intended to reflect biologically more valid entities. Two examples are given here.

Type I and type II schizophrenia

Crow (1985) described two syndromes of schizophrenia, based upon a combination of clinical and neurobiological factors. Type I has an acute onset, mainly positive symptoms, and preserved social functioning during remissions. It has a good response to antipsychotic drugs, associated with dopamine overactivity. By contrast, type II has an insidious onset, mainly negative symptoms, and poor outcome and response to antipsychotic drugs, without evidence of dopamine overactivity but with structural brain changes (especially ventricular enlargement). Subsequent research has not strongly supported the biological subtypes and correlations which are predicted by the model. However, it was important as an example of the renewed focus on the neurobiological aspects of schizophrenia which occurred around that time.

Three clinical sub-syndromes

Liddle (1987) studied patients with chronic schizophrenia and, based on clustering of symptoms, described three overlapping clinical syndromes, which he called reality disturbance, disorganization, and psychomotor poverty (see Table 11.4). These findings have largely been confirmed by later studies. Notably, Liddle then linked these symptom clusters to distinct patterns of neuropsycho-logical deficit and to regional cerebral blood flow (Liddle et al., 1992). The most reproducible finding is the link between psychomotor poverty, impaired performance on frontal lobe tasks, and decreased frontal blood flow.

Other aspects of the clinical syndrome

Cognitive features

Despite Kraepelin’s original term dementia praecox, cognitive impairment was for many years a neglected component of schizophrenia, even though it is substantial and significant (Dickinson and Harvey, 2009). Indeed, it has been argued that neuropsychological abnormality is an invariable feature (Wilk et al., 2005). Impairments are seen across all domains of learning and memory, with disproportionate involvement of semantic memory, working memory, and attention. The deficits average 1 to 2 standard deviations below expected performance, and are present at the first episode; IQ is also reduced (Mesholam-Gately and Giuliano, 2009). Cognitive deficits are greater in early-onset schizophrenia (Rajji et al., 2009). Executive function and attention may be the core deficits, in that they are seen even in patients with otherwise intact cognition.

The time course of neuropsychological involvement in schizophrenia is complex and not entirely clear. People who later develop schizophrenia already have reduced IQ scores during childhood (Woodberry et al., 2008). The onset of illness is associated with further cognitive impairments, which may partially improve after resolution of the acute episode. However, most of the cognitive deficits appear to be trait features, largely independent of other symptom domains. In the seventh decade a proportion of patients undergo a substantial decline in cognitive performance and develop dementia, similar in nature to Alzheimer’s disease, but without any detectable neuropathology (Radhakrishnan et al., 2012). Like many other features of schizophrenia, impaired cognitive performance is also observed in attenuated form in unaffected relatives.

Table 11.4 Cerebral and psychological correlates of three sub-syndromes of chronic schizophrenia

Cognitive aspects of schizophrenia are currently being emphasized for several reasons. First, they are a major determinant of poor functional outcome (Green, 2006). Secondly, they are now viewed as potential therapeutic targets (see p. 290). Thirdly, cognitive features are increasingly conceptualized as being central to the disorder and as underlying the psychotic symptoms (O’Connor et al., 2009). Reflecting these developments, methods are being developed to allow routine in schizophrenia cognitive assessments in schizophrenia (e.g. the MATRICS Battery) (Nuechterlein et al., 2008), and the Brief Cognitive Assessment Tool for Schizophrenia (B-CATS) (Hurford et al., 2011).

Depressive symptoms

As noted earlier, and as recognized since the time of Kraepelin, depressive symptoms commonly occur in schizophrenia, at any phase of the illness, even before the florid positive symptoms become apparent. Indeed, they are prominent features of the prodrome (see below). In addition, about 25% of patients subsequently exhibit persistent and significant depression, called post-schizophrenic depression. Comorbid depression in schizophrenia worsens the functional outcome.

There are several reasons why depressive symptoms may be associated with schizophrenia.

• Depression may be an integral part of schizophrenia. This view is supported by the observation that about 50% of patients with acute schizophrenia experience significant depressive symptomatology, which improves as the psychosis remits.

• In the post-psychotic phase, depressive symptoms may be a response to recovery of insight into the nature of the illness and the problems to be faced. Again, this may happen at times, but it does not provide a convincing general explanation.

• Depression may be a side-effect of medication. This is not the only explanation, as depressive symptoms can occur in the absence of antipsychotic drug therapy.

Depressive symptoms in schizophrenia should not be confused with motor side-effects of medication or negative symptoms. These distinctions are important, but can be difficult to make.

Neurological signs

Neurological signs are a neglected clinical feature of schizophrenia (Chan et al., 2010). They are called ‘soft signs’ because they do not localize pathology to a particular tract or nucleus. They include abnormalities in sensory integration, coordination, and sequencing of complex motor acts; catatonic features and dyskinesias may also be considered under this category (Koning et al., 2010). Neurological signs are seen in unmedicated, first-episode patients (and are therefore separate from the effects of antipsychotic drugs in this regard), but are more common in chronic schizophrenia. The presence of neurological signs correlates with cognitive dysfunction, evidence for developmental anomaly, and diffuse brain pathology, and they are thought to be a manifestation of the neurodevelopmental origins of schizophrenia (Picchioni and Dazzan, 2009). A neurological examination that focuses upon the extrapyramidal system should be part of the routine assessment of a patient who presents with schizophrenia.

Olfactory dysfunction

Patients with schizophrenia have deficits in olfactory function, which affect the identification of, sensitivity to, and memory for odours (Turetsky et al., 2006). The deficits are not attributable to medication or smoking. They are predictive of cognitive and negative symptoms, and may contribute to the lack of social drive that is apparent in many patients (Rupp, 2010).

Water intoxication

A few patients with chronic schizophrenia drink excessive amounts of water, thus developing a state of water intoxication. When severe, it may give rise to severe hyponatraemia, cerebral oedema, seizures, coma, and sometimes death. The ‘drive’ to drink water may include unsuitable sources, such as toilet bowls. The reasons for this behaviour are unknown. Possible mechanisms include a response to a delusional belief, or abnormalities affecting hypothalamic regulation of thirst (Goldman, 2009).

Pain insensitivity

A diminished sensitivity to pain in patients with schizophrenia has long been noted by clinicians, and can on occasion be extreme. It is not related to medication (Potvin and Marchand, 2008). Its cause is unknown. Proposed explanations include thalamic lesions, and the possibility that psychotic symptoms render the patient less concerned by, or distracted from, the pain.

Factors that modify the clinical features

The social and cultural background of the patient affects the content of symptoms. For example, religious delusions are less common now than they were a century ago, and have been replaced by delusions concerned with cloning, HIV, or terrorism. Age also seems to modify the picture. In adolescents and young adults, the clinical features often include thought disorder, mood disturbance, passivity phenomena, thought insertion, and withdrawal. With increasing age, paranoid symptomatology is more common, with more organized delusions.

Intelligence also affects the clinical features, and the psychiatrist’s ability to elicit them. Patients with learning disability usually present with a simple clinical picture, sometimes referred to as pfropfschizophrenie. In contrast, highly intelligent people develop complex delusional systems, and are also better able to articulate, or conceal, their experiences.

The amount of social stimulation has a considerable effect. Under-stimulation is thought to increase negative symptoms, whereas over-stimulation precipitates positive symptoms. Modern psychosocial approaches to treatment are designed to avoid both extremes—the under-stimulation associated with institutionalization, and the excess stimulation of high expressed emotion (see p. 285).

The prodrome of schizophrenia

In recent years increasing attention has been paid to the prodrome of schizophrenia—that is, the period of time during which psychosis is ‘brewing’, when there are identifiable symptoms but before diagnosable criteria are met, and before the patient typically presents for help (Yung and McGorry, 1996). The focus on the prodrome reflects the fact that in many patients this period may last for several years, and that the longer the duration of untreated psychosis, the worse the outcome appears to be. These considerations have led to a rapid growth in ‘early intervention’, with services designed to detect and then prevent emerging cases of schizophrenia (see Chapter 21). The therapeutic aspects and implications are considered on p. 294.

The prodrome is characterized by insidious and shifting profiles of largely non-specific symptoms, including mild psychotic-like positive and negative symptoms, and also commonly mood and anxiety symptoms. Cognitive and social functioning also deteriorates. Various criteria are available to assess and rate the prodrome, including the Comprehensive Assessment of At Risk Mental State (CAARMS). Importantly, many people who are considered to be prodromal do not progress to overt psychosis; typically, only 20–30% do so during a 2- to 3-year follow-up. This has important implications for treatment interventions. Studies are attempting to identify predictors of conversion (Ruhrmann et al., 2010).

For review of the schizophrenia prodrome, see Addington and Lewis (2011).

Diagnosis and classification

This section is concerned mainly with the diagnostic criteria for and classification of schizophrenia as specified in DSM-IV and ICD-10. However, the current approach—and its problems—can be understood better with some knowledge of the historical perspective.

Historical development of ideas about schizophrenia

The development of ideas about schizophrenia is discussed in Box 11.3. To a large extent, they mirror the development of ideas about psychiatric illness in general, reflecting the central position in psychiatry held by schizophrenia during the last century. For a review, see Andreasen (2009).

In the 1960s it was noticed that there were wide divergences in the use of the term schizophrenia, and marked differences in diagnostic practice. This was unsurprising, given the multiple views and traditions summarized in Box 11.3. For example, in the UK and continental Europe, psychiatrists generally employed Schneider’s first-rank symptoms to identify a narrowly delineated group of cases. In the USA, however, interest in psychodynamic processes led to diagnosis on the basis of mental mechanisms, and to the inclusion of a much wider group of cases. First-admission rates for schizophrenia were also much higher in the USA than in the UK.

These discrepancies prompted the two major cross-national studies of diagnostic practice, discussed in Chapter 2 (see p. 29), which proved highly influential not just for schizophrenia but also for the development of diagnostic criteria and classificatory systems, namely the US–UK Diagnostic Project (Cooper et al., 1972), and the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia (IPSS) (World Health Organization, 1973). These findings led to a consensus that agreed diagnostic criteria were required, and the development of standardized methods by which these could be defined and identified, culminating in the current ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia.

In summary, a wide range of views about schizophrenia have been held over the past century since Kraepelin and Bleuler established the concept. With the advent of current classificatory systems, the term now refers to a syndrome which can be diagnosed reliably, which is essential for rational clinical practice. However, as noted in Chapter 3, reliability is not in itself sufficient. For example, use of Schneider’s first-rank symptoms leads to high reliability in diagnosis but has no prognostic value. Moreover, because the cause of schizophrenia is still largely unknown, the syndrome remains of uncertain validity. Until this fundamental question is answered, there will continue to be dispute as to its most important features, diagnostic boundaries, and internal subdivisions.

Classification of schizophrenia in DSM-IV and ICD-10

The classification of schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10 is outlined and compared in Table 11.5. The classifications can be seen to be broadly similar.

DSM-IV

In this classification, schizophrenia is defined in terms of the symptoms in the acute phase and also of the course, for which the requirement is continuous signs of disturbance for at least 6 months (see Table 11.6). The acute symptoms (criterion A) include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech or behaviour, and negative symptoms. At least two of these symptoms must have been present for a period of 1 month (unless successful treatment has occurred). Where subjects have major disturbances of mood occurring concurrently with the acute-phase symptoms, a diagnosis of a schizoaffective disorder or mood disorder with psychotic features should be made.

A further criterion for the diagnosis of schizophrenia is that the patient must have exhibited deficiencies in their expected level of occupational or social functioning since the onset of the disorder. As noted above, for the diagnosis to be made there must have been at least 6 months of continuous disturbance; this can include prodromal and residual periods when acute-phase symptoms, as described above, are not evident. Patients whose symptom duration does not meet this 6-month period criterion will be classified as suffering from schizophreniform disorder or brief psychotic disorder. Other related disorders include delusional disorder (see Chapter 12) and psychotic disorders not otherwise classified (see below).

In DSM-IV, schizophrenia is divided into a number of subtypes, defined by the predominant symptomatology at the time of evaluation. After at least 1 year has elapsed since the onset of active-phase symptoms, DSM-IV also allows the disorder to be classified by longitudinal course, and specification of the pattern of relapse and remission.

Table 11.5 Classification of schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders in ICD-10 and DSM-IV*

Table 11.6 Criteria for schizophrenia in DSM-IV

ICD-10

The ICD-10 criteria for schizophrenia (see Table 11.7) place more reliance than DSM-IV on first-rank symptoms, and requires a duration of only 1 month, excluding prodromal symptoms. There are several clinical subtypes, which differ from DSM-IV mainly in the inclusion of categories of simple schizophrenia and post-schizophrenic depression. As in DSM-IV, cases in which symptoms of schizophrenia are accompanied by prominent mood disturbances are classified as schizoaffective disorders.

Table 11.7 Criteria for schizophrenia in ICD–10

Certain aspects of personality are associated with schizophrenia, clinically and genetically. ICD-10 includes schizotypal disorder among schizophrenic disorders, whereas in DSM-IV this condition is classified as a personality disorder. Schizotypal disorder is associated with social isolation and restriction of affect; in addition, there are perceptual distortions, with disorders of thinking and speech and striking eccentricity or oddness of behaviour.

Similarly to DSM-IV, ICD-10 classifies delusional disorders separately from schizophrenia (see Chapter 12). In addition, a group of acute and transient psychotic disorders are recognized that have an acute onset and complete recovery within 2–3 months (see below).

Summary of the differences between DSM-IV and ICD-10

• ICD-10 places greater weight on Schneider’s first-rank symptoms. DSM-IV emphasizes course and functional impairment.

• ICD-10 requires a duration of illness of 1 month, whereas DSM-IV requires a duration of 6 months.

• Schizotypal disorder is included in ICD-10, but is categorized as a personality disorder in DSM-IV.

• ICD-10 includes some additional subtypes, namely simple schizophrenia and post-schizophrenic depression.

• Disorganized schizophrenia in DSM-IV is called hebe-phrenic schizophrenia in ICD-10.

Schizophrenia-like disorders

Whatever definition of schizophrenia is adopted, there will be cases that resemble schizophrenia in some respects and yet do not meet the criteria for diagnosis. In DSM-IV and ICD-10, these disorders are divided into four groups:

1. delusional disorders (paranoid psychoses)

2. brief disorders

3. disorders accompanied by prominent affective symptoms

4. disorders without all of the symptoms required for schizophrenia.

Delusional disorders are discussed in Chapter 12. The latter three groups are discussed here.

Brief disorders

DSM-IV uses the term brief psychotic disorder to refer to a syndrome characterized by at least one of the acute-phase positive symptoms shown in Table 11.6. The disorder lasts for at least 1 day but not more than 1 month, by which time full recovery has occurred. The disorder may or may not follow a stressor, but psychoses induced by the direct physiological effects of drugs or medical illness are excluded. Schizophreniform disorder is a syndrome similar to schizophrenia (meeting criterion A) which has lasted for more than 1 month (and so cannot be classified as brief psychotic disorder), but for less than the 6 months required for a diagnosis of schizophrenia to be made. Social and occupational dysfunction are not required in order to make the diagnosis.

In ICD-10, the grouping is acute and transient psychotic disorder. These disorders are of acute onset, and complete recovery within 2–3 months is the rule. The disorder may or may not be precipitated by a stressful life event. The category is then subdivided into several overlapping and somewhat confusing subtypes. In the first two, acute polymorphic psychotic disorders, with or without symptoms of schizophrenia, hallucinations, delusions, and perceptual disturbance are obvious, but change rapidly in nature and extent. There are often accompanying changes in mood and motor behaviour. Bouffée délirante and cycloid psychosis (see Box 11.3) are given as synonyms for these categories. A third subtype, acute schizophrenia-like psychotic episode, is a non-committal term for cases that meet the symptom criteria for schizophrenia but last for less than a month. Residual cases that do not fit these subtypes of acute psychosis are called other acute psychotic episodes. Overall, the ICD-10 category identifies a heterogeneous group of disorders in terms of outcome (Singh et al., 2004).

Schizophrenia-like disorders with prominent affective symptoms

Some patients have a more or less equal mixture of schizophrenic and affective symptoms. As mentioned earlier, such patients are classified under schizoaffective disorder in both DSM-IV and ICD-10.

The term schizoaffective disorder has been used in several distinct ways. It was first applied by Kasanin (1994/1933) to a small group of young patients with severe mental disorders characterized by a very sudden onset in a setting of marked emotional turmoil. The psychosis lasted a few weeks and was followed by recovery.

The current definitions differ substantially from this description. DSM-IV requires that there should have been an uninterrupted period of illness during which, at some time, there is either a major depressive episode, a manic episode, or a mixed episode concurrent with symptoms that meet criterion A for schizophrenia. During this continuous episode of illness, the acute-phase psychotic symptoms must have been present for at least 2 weeks in the absence of prominent mood symptoms (or the diagnosis would be a mood disorder with psychotic features). However, the episode of mood disturbance must have been present for a substantial part of the illness. The definition of schizoaffective disorder in ICD-10 is similar. It also specifies that the diagnosis should only be made when both definite schizophrenic and definite affective symptoms are equally prominent and present simultaneously, or within a few days of each other. (This is an important point. The label ‘schizoaffective’ should not be applied just because a patient has an isolated symptom or two consistent with both diagnoses, or because the assessment has not been sufficiently detailed to identify the primary diagnosis.) ICD-10 classifies schizoaffective disorder according to whether the mood disturbance is depressive, manic, or mixed. In DSM-IV schizoaffective disorder is specified as either depressive type or bipolar.

Family studies have shown that the more recent diagnostic concepts of schizoaffective disorder delineate a syndrome in which first-degree relatives have an increased risk of both mood disorders and schizophrenia. In addition, the outcome of schizoaffective disorder is generally thought to be better than that for schizophrenia, with negative symptoms rarely developing (Tsuang et al., 2000).

As noted above, it is not uncommon for patients with schizophrenia to develop depression as the symptoms of acute psychosis subside. This is recognized in ICD-10 as post-schizophrenic depression, where prominent depressive symptoms have been present for at least 2 weeks while some symptoms of schizophrenia (either positive or negative) still remain.

Persistent disorders without all of the required symptoms for schizophrenia

A difficult problem is presented by cases that have longstanding schizophrenia-like symptoms but which do not fully meet the diagnostic criteria. There are four groups.

1. Patients who have exhibited the full clinical picture of schizophrenia in the past, but who no longer have all of the symptoms required to make the diagnosis. These cases are classified as residual schizophrenia in both DSM-IV and ICD-10.

2. People who from an early age have behaved oddly and shown features seen in schizophrenia—for example, ideas of reference, persecutory beliefs, and unusual types of thinking. When long-standing, these disorders can be classified as personality disorders in DSM-IV (schizotypal personality disorder), or with schizophrenia in ICD-10 (schizotypal disorder). Because of a suggested close relationship to schizophrenia, these disorders have also been called latent schizophrenia, or part of the schizophrenia spectrum.

3. People with social withdrawal, lack of initiative, odd behaviour, and blunting of emotion, in whom positive psychotic symptoms are never known to have occurred. A variety of terms may be applicable, including simple schizophrenia (see p. 258), schizoid personality disorder (see p. 145), and Asperger’s syndrome (see p. 653). (We advise caution in using the terms simple schizophrenia or latent schizophrenia. Both of these lack utility—since treatment is rarely indicated or wanted—and represent speculative diagnostic labels for what many would consider simply to be eccentricity.)

4. People with stable, persistent delusions but without other features of schizophrenia (see Chapter 12).

Comorbidity

Many patients with schizophrenia also meet the criteria for another psychiatric diagnosis, complicating diagnosis and treatment, and worsening the outcome. The example of depression (which occurs in 50% of cases) has already been mentioned. The estimated lifetime prevalence of any substance abuse is 47%, and of alcohol abuse is 21%. Psychiatric disorders often comorbid with schizophrenia include post-traumatic stress disorder (29%), obsessive–compulsive disorder (23%), and panic disorder (15%). For a review, see Buckley et al. (2009).

Differential diagnosis

We have already described how current classifications include schizophrenia-like disorders as well as schizophrenia, but the boundary between them is blurred and to some extent arbitrary. Similarly, there is no clear distinction between disorders that are considered to be variants of schizophrenia, and some which are viewed as being part of its differential diagnosis. For example, delusional disorders are often included in both categories, while schizotypal disorder is classified as a personality disorder in DSM-IV but with schizophrenia in ICD-10. Such difficulties reflect the unknown validity of the syndrome(s), and are unlikely to be resolved until the classification is based upon aetiology or other empirically validated markers.

With these caveats in mind, current diagnostic practice requires schizophrenia to be distinguished from a number of other disorders, which are listed below.

• Organic syndromes. Acute schizophrenia can be mistaken for delirium, especially if there is pronounced thought disorder and a rapidly fluctuating affect and mental state. Careful observation is needed for clouding of consciousness, disorientation, and other features of delirium (see Chapter 13). Schizophrenia-like disorders can also occur, in clear consciousness, in a range of neurological and medical disorders. These conditions are referred to as a psychotic disorder secondary to a general medical condition (DSM-IV), organic delusional disorder (ICD-10), or simply as secondary schizophrenia. Classic examples include temporal lobe epilepsy (complex partial seizures), general paralysis of the insane, and metachromatic leukodystrophy (see Chapter 13, and Hyde and Ron, 2011). Visual, olfactory, and gustatory hallucinations are said to be suggestive of an organic disorder. The occurrence of organic schizophrenia-like disorders emphasizes the importance of a careful medical history and physical examination (and investigations, if indicated) in all such patients. One study in London found that 10 out of 268 cases (3.7%) of ‘first-episode schizophrenia’ had an organic cause other than substance misuse (Johnstone et al., 1987).

• Drug-induced states (including substance misuse). Certain prescribed drugs, particularly steroids and dopamine agonists, can cause florid psychotic states. Psychoactive substance misuse, particularly with psychostimulants or phencyclidine, and also alcohol, should always be considered in the presentation of schizophrenia-like psychoses. Urine or hair testing can be helpful in diagnosis, as is the temporal association between drug use and symptoms. However, the high prevalence of recreational drug use in young adults means that a clear distinction between a drug-induced psychosis and schizophrenia is not always possible.

• Mood disorder with psychotic features. The distinction of schizophrenia (and schizoaffective disorder) from affective psychosis depends on the degree and persistence of the mood disorder, the relationship of any hallucinations or delusions to the prevailing mood, and the nature of the symptoms in any previous episodes. The distinction from mania in young people can be particularly difficult, and sometimes the diagnosis can only be clarified by longer-term follow-up. A family history of mood disorder may be a useful pointer.

• Delusional disorders. These disorders (see Chapter 12) are characterized by chronic, systematized paranoid delusions, but lack other symptoms of schizophrenia, and many areas of the mental state are unremarkable.

• Personality disorder. Differential diagnosis from personality disorder, especially of the paranoid, schizoid, or schizotypal forms, can be difficult when insidious changes are reported in a young person, or paranoid ideas are present. Prolonged observation may be required to detect genuine symptoms of psychosis, and the additional features indicative of schizophrenia. Some patients with borderline personality disorder also exhibit transient psychotic symptoms, although the presence of affective instability and other features means that there should rarely be diagnostic confusion with schizophrenia.

Epidemiology

Schizophrenia is a disorder with a low incidence and a high prevalence. Estimates of both have varied markedly, reflecting the methodology and diagnostic criteria used, as well as genuine differences between populations. Recent reviews and meta-analyses have helped to clarify the estimates and their confidence intervals. For reviews, see McGrath et al. (2008) and Jablensky et al. (2011).

Incidence

The annual incidence using current diagnostic criteria is 0.16–1.00 per 1000 population using a broad definition; for more restrictive diagnoses, the incidence is about two to three times lower (Jablensky et al., 2011). A systematic review provided an estimated mean incidence of 0.24 per 1000, but an estimated median incidence of 0.15 per 1000. This difference reflects a skew, with many estimates in the upper tail of the distribution, which in turn results from studies that sampled from within populations with a high incidence (e.g. migrant groups, as discussed below). These recent analyses strongly question the belief, largely arising from the World Health Organization Ten Country Study (Jablensky et al., 1992), that schizophrenia has a similar incidence (and prevalence) in all populations (McGrath et al., 2008). There may also be variations in incidence related to latitude, and urban–rural differences (see p. 274).

There has been debate as to whether the incidence of schizophrenia is falling in industrialized countries, stimulated by a Scottish study (Eagles and Whalley 1985). However, studies vary in their findings. In any event, whether observed declines represent a true fall in inception rate, as opposed to changes in diagnostic criteria or their implementation, remains unclear (Jablensky et al., 2011).

Prevalence

Systematic reviews indicate a lifetime prevalence of about 4 per 1000, and a lifetime morbid risk of 7.2 per 1000 (McGrath et al., 2008). These are median values because the data are skewed; the means are higher, at 5.5 and 11.9 per 1000, respectively. The latter figure is more consistent with the frequent statement that about 1 in 100 people develop schizophrenia, but the value of 7 in 1000 is statistically more appropriate. As with incidence, prevalence estimates are higher in men than in women, in some migrant groups, and at higher latitudes.

Age at onset

Schizophrenia can begin at any stage of life, from childhood to old age. The usual onset is between 15 and 54 years, most commonly in the mid-twenties; more detailed analyses suggest that there are two peaks, one at 20 years of age, and a second peak at 33 years. Gender differences in age of onset may explain these observations, as men have a single peak in their early twenties, whereas women have a broader range of age of onset, and a second peak in their fourth decade.

Late-onset schizophrenia is discussed in Chapter 18.

Gender

In addition to gender differences in age of onset, meta-analyses show that schizophrenia is more common in men than in women, with a male:female ratio of 1.4. The difference is more marked for severe cases, and is not due to differences in referral, identification, or age of onset. It has been attributed to the neuroprotective effects of oestrogen, but the evidence for this is poor. Gender differences in genetic and epigenetic risk factors may also be relevant. For a general review of gender issues in schizophrenia and its management, see Grossman et al. (2008) and Abel et al. (2010).

Fertility

Whether patients with schizophrenia show decreased fertility has been a controversial topic, not least because of its implications for debate about whether schizophrenia is a ‘disease’, and with regard to its genetic basis. A recent meta-analysis showed a substantial reduction in fertility in people with schizophrenia (about 40% of that expected), which was greater in men than in women (Bundy et al., 2011). These figures are difficult to interpret as being an intrinsic feature of schizophrenia, since opportunities for patients to have children have historically been limited by institutionalization, as well as by the amenorrhoea and sexual dysfunction caused by antipsychotic drugs. On the other hand, the unaffected siblings of patients also show a slight reduction in fertility (Bundy et al., 2011).

Other aspects of schizophrenia epidemiology

The course and outcome of schizophrenia are discussed later in the chapter, and other epidemiological aspects relevant to aetiology are considered in the next section.

Aetiology

Overview

Views about the aetiology of schizophrenia have been inextricably linked with the controversies regarding its nature and classification (discussed earlier in this chapter and in Chapter 3).

Schizophrenia therefore exemplifies the whole range of biological, psychological, and social factors considered to be important in psychiatric causation (see Chapter 5 and Table 11.8), and the methods which have been applied to try to identify them. This section summarizes the current knowledge and theories in each domain, and also mentions some outdated but influential views. It adopts a broad definition of aetiology, and includes pathogenesis and pathophysiological findings.

Key aspects of the present consensus regarding the aetiology of schizophrenia can be summarized as follows. The most important influence is genetic, with about 80% of the risk of schizophrenia being inherited. The mode of inheritance is complex, and the genes—some of which have recently been identified—act as risk factors, not determinants of illness. A number of environmental factors contribute, too, many of which appear to act prenatally, and which interact with the genetic predisposition. Together, these and subsequent risk factors lead to a neurodevelopmental disturbance that renders the individual vulnerable to the later emergence of symptoms, and that manifests itself premorbidly in a range of behavioural, cognitive, and neuroanatomical features. In schizophrenia, there are slight but robust differences in brain structure and function, supporting the view that the syndrome is a disorder of brain connectivity. Acute psychosis is associated with excess dopamine neurotransmission, which may be secondary to abnormalities of the glutamate system. Psychosocial factors have been relatively neglected recently, but significantly influence the onset and course of illness. Finally, it is emphasized that there are few certainties about the aetiology of schizophrenia, and even where the facts are robust, their interpretation often remains unclear.

For contemporary reviews of the aetiology and conceptualization of schizophrenia, see Tandon et al. (2008), van Os and Kapur (2009), and Insel (2010).

Genetics

Family, twin, and adoption studies have all been applied extensively in schizophrenia, and cumulatively provide irrefutable evidence for a major genetic contribution to the syndrome (Riley and Kendler, 2011). Such studies set the context for the current wave of molecular studies designed to identify the causative genes and genetic abnormalities.

Table 11.8 Examples of aetiological factors and theories in schizophrenia

Family studies

The first systematic family study was conducted in Kraepelin’s department by Ernst Rudin, who showed that the rate of dementia praecox was higher among the siblings of probands than in the general population. Later research used better criteria for proband selection and diagnosis, and yielded estimates of an average lifetime risk of around 5–10% among first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia, compared with 0.2–0.6% among first-degree relatives of controls (see Table 11.9). Taken together, the family studies provide clear evidence of a familial aetiology, but do not distinguish between genetic effects and the influence of the family environment.

Table 11.9 Approximate lifetime risk of developing schizophrenia for relatives of a proband with schizophrenia

Family studies can also be used to determine whether the liability to schizophrenia and other disorders (e.g. bipolar disorder) is transmitted independently, which should be the observed pattern if the two disorders are separate syndromes with differing aetiology. However, the findings from the various studies have been contradictory, with some researchers arguing for separate familial transmission of mood disorders and schizophrenia, while others suggest that what is transmitted is a shared vulnerability to psychosis. Two broad conclusions can be drawn (see Table 11.10 and Kendler and Diehl, 1993). First, the risk of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and schizotypal and paranoid personality disorders is increased in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Secondly, the risk of both schizophrenia and mood disorder is increased in first-degree relatives of patients with schizoaffective disorder.

Twin studies

Twin studies were introduced on p. 99. They have been of considerable importance in research on schizophrenia, providing unequivocal evidence of the heritability of this disorder.

The first substantial twin study was conducted in Munich by Hans Luxenberger in the 1920s. He found concordance in 11 of his 19 monozygotic (MZ) pairs and in none of his 13 dizygotic (DZ) pairs. Subsequent investigations, although differing with regard to rates, all agree that concordance is several-fold higher in MZ than in DZ twins. Representative figures for concordance are 40–50% for MZ pairs and about 10% for DZ pairs (Cardno and Gottesman, 2000).

Table 11.10 Lifetime risk of developing psychiatric disorder in first-degree relatives of probands with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and controls

Modern twin studies also produce estimates of heritability (the proportion of liability to schizophrenia in the population which can be attributed to genes), and can separate environmental factors into those that are unique to the individual and those which are shared with others. A meta-analysis (Sullivan et al., 2003) thereby confirmed the substantial heritability of schizophrenia (81%; 95% confidence interval, 73–90%). These data unambiguously show that inheritance (i.e. genes) contribute the majority of the risk for schizophrenia. However, there are caveats about the interpretation of heritability figures. For example, the estimates make some assumptions about the ‘genetic architecture’ (i.e. how the genetic factors operate) and include gene–environment interactions. The meta-analysis also showed, less predictably, that most of the environmental contribution comes from shared rather than individual-specific influences (11%; 95% confidence interval, 3–19%). The identity of these shared environmental factors is unknown.

It is worth noting that, among discordant MZ twins, the risk of schizophrenia is increased equally in children of the unaffected and the affected co-twin. This indicates that the unaffected co-twin indeed had the same genetic susceptibility to developing schizophrenia as the affected twin, but for some reason did not express the phenotype. This is most probably due to environmental protective factors, or chance (‘stochastic processes’), affecting the penetrance or expression of the genetic predisposition. Moreover, unaffected identical co-twins do exhibit some mild features of schizophrenia (in terms of symptoms and biological findings) which fall well short of being diagnostically significant, but which are greater than those seen where neither member of a twin pair has schizophrenia. This probably reflects a partial expression of the risk genotype.

Adoption studies

Heston (1966) studied 47 adults who had been born to mothers with schizophrenia and separated from them within 3 days of birth. As children they had been brought up in a variety of circumstances, although not by the mother’s family. At the time of the study their mean age was 36 years. Heston compared them with controls matched for circumstances of upbringing, but whose mothers had not suffered from schizophrenia. Among the offspring of the affected mothers, five were diagnosed as having schizophrenia, compared with none of the controls. The rate for schizophrenia among the adopted-away children was comparable with that among children with a schizophrenic parent who remained with their biological family.

Further evidence came from a series of Danish studies that started in the 1960s. In one major project (Kety et al., 1975), two groups of adoptees were identified—a group of 33 adoptees who had schizophrenia, and a matched group who were free from schizophrenia. Rates of disorder were compared in the biological and adoptive families of the two groups of adoptees. The rate for schizophrenia was higher among the biological relatives of the adoptees with schizophrenia than among the relatives of the controls, a finding which supports the genetic hypothesis. Furthermore, the rate for schizophrenia was not increased among couples who adopted the affected children, which suggests that environmental factors were not of substantial importance. Follow-up studies using a national sample of Danish adoptees confirmed that biological first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia have an approximately tenfold increased risk of suffering from schizophrenia or a related (‘spectrum’) disorder (Kety et al., 1994).

The data from adoption studies thus strongly support the view that genetic factors explain the familial clustering of schizophrenia. However, it should be noted that they cannot control for the prenatal environment, which other studies suggest is important. Nor can they rule out an interaction between environmental causes in the adoptive family and genetic predisposition; indeed, Finnish data show that adoptees at high genetic risk of schizophrenia are more sensitive to adverse upbringing (Tienari et al., 2004).

The mode of inheritance

The frequency profile of schizophrenia among people with different degrees of genetic proximity to the proband does not fit any simple Mendelian pattern, as would be expected if the disorder was caused by a single major gene (Gottesman, 1991). Instead, the evidence suggests that schizophrenia arises from the cumulative effect of several genes, as a so-called complex or non-Mendelian disorder. The liability to schizophrenia lies along a continuum in the population, and is expressed when a certain threshold of genetic susceptibility is exceeded. No genes are either necessary or sufficient, and they act as risk factors, not determinants. Within this model, a range of genetic mechanisms and subtypes are possible—for example, concerning the nature of the genetic abnormalities themselves (e.g. single-nucleotide polymorphisms and copy-number variations), whether the gene variants are common or rare in the population, and whether a given gene acts independently or interactively with other genes (epistasis). For review, see Owen et al. (2010) and Bassett et al. (2010).

What is heritable?

Identification of the genes responsible for a condition is much easier if the boundaries of the inherited phenotype are known. However, this is a circular argument, as it is ultimately the identification of causative genes that, whenever possible, defines diseases. The uncertain boundaries between schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders and mood disorders have already been mentioned. Recent molecular genetic studies strongly support the view that schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are not distinct disorders, but lie along a genetic spectrum (Owen et al., 2007), and have also suggested that other aspects of the genetic predisposition to schizophrenia are shared with autism and with learning disability (Bassett et al., 2010).

Another possibility is that it is particular components of schizophrenia, or other features associated with it, which are actually being inherited. Much evidence suggests that there are such features, called endophenotypes or intermediate phenotypes (see p. 104), which are more closely related to the genes, and therefore more aetiologically valid. A range of heritable endophenotypes of schizophrenia are known, including evoked potentials, working memory, brain structure, and eye-tracking dysfunction. Whether any of these components become part of a redefined syndrome or syndromes of schizophrenia will depend upon confirmation of their genetic basis, and demonstration that they have reliability and utility (e.g. in predicting outcome or therapeutic responsiveness).

Schizophrenia susceptibility genes

Despite the high heritability of the disorder, and the large number of studies that have been conducted, it has proved difficult to identify schizophrenia genes. This difficulty probably reflects the various issues already mentioned, notably the uncertainty as to the phenotype being inherited, and the existence of multiple genes of small effect which are thus hard to detect. However, significant progress has been made in the past few years. This is due to a combination of methods which were introduced in Chapter 5. Each has contributed to the current state of knowledge, although at present not all of the findings from each approach can readily be integrated.

A recent meta-analysis of 32 genome-wide linkage studies identified several chromosomal regions (loci) which, by reasonably stringent statistical criteria, show linkage to schizophrenia (Ng et al., 2009), namely regions of chromosome 1, 2q, 3q, 4q, 5p, 8p, and 10q (p and q refer to the short and long arms, respectively). This suggests that a gene (or genes) contributing to schizophrenia risk is located at each of these regions, although both false-positive and false-negative findings are likely.

Several approaches have been taken to finding schizophrenia genes themselves, each of which has had some successes.

First, testing for genetic association with schizophrenia of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes within these chromosomal loci led to the discovery of several schizophrenia genes, notably neuregulin, dysbindin, and G72.

Secondly, chromosomal abnormalities that confer an increased risk of schizophrenia were used as a rationale for searching for genes in that region. The best example is velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS, also known as di George syndrome), which is caused by deletion of one copy of chromosome 22q11 (hence its alternative name, 22q11 hemideletion syndrome). It is a relatively common cytogenetic anomaly, occurring in 1 in 4000 live births, and causes a range of physical abnormalities and cognitive impairment (Murphy, 2002). Of relevance here, it is also associated with psychosis (either schizophrenia-like or affective) in about 30% of individuals. Thus even though VCFS is a rare cause of schizophrenia overall, 22q11 is implicated as a locus for schizophrenia genes in general. The resulting focus on genes within this region has identified several which may be involved in schizophrenia risk (Karayiorgou et al., 2010). Another example in this category is disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1), a gene on chromosome 1 which was identified after extensive study of a large Scottish family in which a translocation between chromosomes 1 and 11 is linked to a high incidence of schizophrenia (and other psychiatric disorders) (Porteous et al., 2006).

Thirdly, ‘candidate genes’ (i.e. those implicated on the basis of biological theories of, or findings in, schizophrenia) have been studied. This approach has not proved very successful, but has provided some evidence for the involvement of dopamine D2 and D3 receptors.

Fourthly, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (see p. 104) have been used. These have produced the best statistical evidence of all the approaches to date, with several genes, notably for miR137, ZNF804A, and the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) locus. However, for various reasons these studies may also miss important genes and genetic abnormalities (Mitchell and Porteous, 2011).

Finally, analysis of copy-number variation (CNV) (see p. 101) has been used. There is now good evidence that schizophrenia is associated with an increased number of CNVs, especially deletions (see Table 11.11). (VCFS, mentioned earlier, can be regarded as a large CNV.) The CNVs can be anywhere in the genome, but genes involved in neurodevelopment and synaptic function may be especially important. CNVs can either be inherited, or arise de novo in an individual (Levinson et al., 2011). It is unclear how important, overall, CNVs will prove to be compared with other forms of genetic variation (e.g. polymorphisms) in the causation of schizophrenia (Bassett et al., 2010).

Table 11.11 summarizes the current evidence, but it is important to note that this is ‘work in progress.’ Some of the findings may not be replicated, and other genes will undoubtedly emerge. There is also a considerable divergence of opinion as to how the current data should be interpreted (Kim et al., 2011). At present it is not possible to state how many susceptibility genes for schizophrenia exist, nor is their relative importance known.

Crow’s lateralization hypothesis

A very different view of the aetiology of schizophrenia has been proposed by Crow (2002). He argues that schizophrenia is due to a single gene, which is also responsible for two unique properties of the human brain, namely cerebral asymmetry and language. No other genes, or environmental factors, are required. For various reasons, the gene is postulated to reside at a particular part of the sex chromosomes, and its abnormality is one of its epigenetic regulation, not its DNA sequence. Protocadherin 11XY gene is the leading candidate. This theory is ingenious but is not widely supported (O’Donovan et al., 2008).

The biology of schizophrenia genes

Efforts are under way to understand the function of the genes implicated in schizophrenia, and how this effect can be explained biologically. One proposal is that many of the genes may converge upon the development, functioning, and plasticity of synapses, particularly glutamatergic ones (Harrison and Weinberger, 2005). The molecular basis with regard to how and why the variants increase schizophrenia is unknown, in part because, with few exceptions, several (or many) different schizophrenia-associated variants have been reported in each gene, and it is not known which of them is the causal one. Nevertheless, at present it is thought that the genetic variants affect the regulation and expression of the gene in a way that is deleterious for brain development or functioning. Interestingly, forms of each gene (‘isoforms’) which are expressed preferentially in the brain (rather than more widely in the body), and which are enriched in fetal life, seem to be particularly implicated (Kleinman et al., 2011).

To complicate matters, there is increasing evidence that schizophrenia risk genes do not operate independently, but interact with each other (epistasis) in biologically meaningful ways. For example, a recent study of the neuregulin signalling pathway found only weak evidence for individual genes being associated with schizophrenia, but individuals who had risk variants in neuregulin 1, and its receptor, and a downstream protein, had a markedly increased risk of schizophrenia (Nicodemus et al., 2010). Genes may also affect an individual’s vulnerability to environmental risk factors, as discussed below.

Table 11.11 Susceptibility loci and genes for schizophrenia

Environmental risk factors

Despite the prominent genetic component, the twin studies discussed earlier, along with many epidemiological and other studies, show that environmental factors are also important in the aetiology of schizophrenia. A range of factors, especially pre- and perinatal ones, have been identified. This section describes the main biological factors; social influences are covered in a subsequent section. For reviews of environmental risk factors, see van Os et al. (2010) and McGrath and Murray (2011).

Obstetric complications

Rates of schizophrenia are increased in individuals who experienced obstetric complications, compared with their unaffected siblings or normal controls. Meta-analyses suggest an odds ratio of about 2 (Geddes et al., 1999; Cannon et al. 2002). A range of exposures are associated with increased risk, including antepartum haemorrhage, diabetes, low birth weight, asphyxia, and Rhesus incompatibility. Obstetric complications may be more relevant in individuals who have a genetic predisposition to schizophrenia (McNeil et al., 2000), a view which is supported by recent findings of interactions between schizophrenia risk genes and birth complications (Nicodemus et al., 2008).

The association of obstetric complications with schizophrenia has several possible explanations. They might be directly causal (e.g. via fetal hypoxia), or a reflection of pre-existing fetal abnormality, or even a reflection of maternal characteristics (e.g. a mother’s antenatal health behaviour).

Maternal influenza and other infections

Several studies have suggested that fetuses exposed during the second trimester to influenza, especially the 1957 influenza A2 pandemic, have an increased risk of schizophrenia. Some biological support for this association was provided by animal studies which showed that prenatal influenza affects fetal brain development. Additional support emerged with the demonstration that serological evidence of influenza infection during early pregnancy was associated with a sevenfold increase in risk of schizophrenia in the offspring (Brown et al., 2004). However, many other studies, and a meta-analysis of the 1957 pandemic, have yielded negative results (Selten et al., 2010), and a relationship between influenza and schizophrenia has been hard to establish.

Several other maternal (and childhood) infections have also been associated with schizophrenia, including toxoplasmosis, herpes simplex virus 2, and rubella. For a review of this subject, see Brown and Derkits (2010).

Maternal malnutrition

Children born to mothers who experienced famine early in their pregnancy have an increased risk of schizophrenia, with an odds ratio of about 2. This was shown initially in children born after the Dutch ‘Hunger Winter’ of 1944, and subsequently in two large Chinese populations that were exposed to famines in the 1960s. It is not known whether the cause is related to general malnutrition or lack of specific micronutrients, nor is it clear whether less extreme fluctuations in nutritional status during pregnancy are relevant to schizophrenia risk. For a review, see Brown and Susser (2008).

Winter birth

Schizophrenia is slightly more frequent among people born in the winter than among those born in the summer (Davies et al., 2003). It has been shown in both the northern and southern hemispheres, and becomes more prominent at higher latitudes. Winter birth may be more common in patients without a family history of schizophrenia. The explanation for the winter birth effect is unknown. It has been linked to the prevalence of influenza earlier in the winter, and to sunshine and vitamin D levels around the time of birth, but could also be related to the time of conception, via seasonal fluctuations in the genetic make-up of gametes.

Paternal age

A replicated finding is that schizophrenia is associated with paternal age, especially in those without a family history of psychosis. One large study found that the risk increased by almost 50% for each 10-year increase in paternal age (Sipos et al., 2004). The favoured explanation has been that the frequency of de novo genetic mutations in sperm is age related. However, a recent study shows that the phenomenon is only observed for a man’s first-born child, and not for subsequent ones (Petersen et al., 2011), which makes this explanation unlikely. Instead, the paternal age effect may be related to how personality (or relationship factors) modify the age at which a man first fathers a child.

Child development

Parnas et al. (1982) reported a study of 207 children of mothers with schizophrenia who were first assessed when they were 8–12 years of age and then again, as adults, 18 years later, by which time 13 individuals had developed schizophrenia and 29 had ‘borderline schizophrenia.’ Of the measures that were used on the first occasion, those that predicted schizophrenia were poor rapport at interview, being socially isolated from peers, disciplinary problems mentioned in school reports, and parental reports that the person had been passive as a baby.

In a national birth cohort of more than 16 000 children who were prospectively studied over a 16-year period, those who developed schizophrenia could be distinguished at the age of 11 years, if not earlier, by greater hostility towards adults, and by speech and reading difficulties (Done et al., 1994). This difference was apparent compared to those who grew up to develop neurotic illness, as well as those who remained well. In a similar study, Jones et al. (1994) found that children who eventually developed schizophrenia showed delayed milestones and speech problems, together with lower education test scores and less social play. A graded relationship between delayed milestones (e.g. age at walking) and schizophrenia has been confirmed in several subsequent cohorts. Finally, Walker and colleagues have shown that the behaviour of children (including motor acts in infants), as recorded in home movies and videotapes, is also associated with later schizophrenia (Schiffman et al., 2004).

Overall, there is good evidence that individuals who will develop schizophrenia show increased rates of intellectual and motor dysfunction and poor social competence in childhood. However, it is unclear how specific these changes are, or how they may be related to the subsequent development of the illness. Most of the children who were destined to develop schizophrenia were not considered clinically abnormal at the time, and many children who perform poorly on these indices do not develop schizophrenia. Nevertheless, the findings support an early neurodevelopmental contribution to schizophrenia (see p. 282).

Substance use

As discussed earlier, the high prevalence of drug and alcohol use in patients with schizophrenia is well established, but whether substance misuse plays a causal role in schizophrenia is more controversial. If substance use is considered to have directly caused or precipitated the psychosis, it is diagnosed as such, and not as schizophrenia. However, there is evidence that prior use of some drugs, particularly cannabis, is associated with an increased risk of later developing schizophrenia. Andreasson et al. (1987) followed up over 45 000 Swedish conscripts for 15 years, and found that the relative risk of developing schizophrenia was 2.5 times higher in subjects who used cannabis, with a sixfold increase in risk for heavy users. These data could be interpreted in two ways—first, that cannabis misuse is indeed a risk factor for schizophrenia, and secondly, that those predisposed to develop the illness (or who are in the prodrome) tend to misuse cannabis. Recent studies support a genuine causal contribution, with early (and heavy) use of cannabis conferring the greatest excess risk (Moore et al., 2007). Moreover, the risk is greater in those predisposed to psychosis for other reasons, including genetic factors (Caspi et al., 2005; van Winkel et al., 2011). However, the magnitude of the cannabis risk for psychosis, and its implications for public health policy, remain controversial (Hall and Degenhardt, 2011) (see also Chapter 17).

Other risk factors

Many other risk factors have been reported to be associated with schizophrenia. For example, earlier studies suggested that head injury is a risk factor for schizophrenia and other psychoses. However, the evidence for this is weak (David and Prince, 2005). For a review, see McGrath and Murray (2011).

Neurobiology

Schizophrenia is at the forefront of attempts to understand psychiatric disorders in terms of alterations in brain structure and function, utilizing the whole range of contemporary neuroscientific concepts and techniques. For reviews of this subject, see Harrison (2009) and van Os and Kapur (2009).

Structural brain changes

Whether there is a neuropathology associated with schizophrenia has been a matter of debate for over a century. The search began with Alois Alzheimer, who spent a decade studying the brains of patients with dementia praecox before he reported the case of presenile dementia with which his name is associated. The failure of Alzheimer and others to identify reliable, characteristic brain changes was central to the view of schizophrenia as a functional disorder rather than an organic one. However, evidence has accrued over the past 30 years which disproves the null hypothesis that there are no structural differences in the brain in schizophrenia, although the details and interpretation of the neuropathology remain poorly understood, and the findings are not clinically useful in the diagnosis of individual patients. The main findings are summarized in Table 11.12.

Structural imaging

In a landmark study, Johnstone et al. (1976) used the novel technique of computerized tomography (CT), and found significantly larger ventricles in 17 elderly hospitalized patients with schizophrenia than in 8 healthy controls. Lateral ventricular enlargement in schizophrenia had been reported decades previously using pneumoencephalography, but it was the study by Johnstone and colleagues which stimulated renewed interest. A large number of subsequent imaging studies, mostly using MRI, have confirmed and extended those findings.

A meta-analysis of MRI studies concluded that there are reliable and significant differences in the volumes of the whole brain, lateral and third ventricles, and hippocampus in individuals with schizophrenia (Wright et al., 2000). The ventricular enlargement, and probably also the other changes, shows a unimodal distribution in patients, indicating that the abnormality is not confined to an ‘organic’ subtype of schizophrenia. There is no clear association with gender. The differences are present in first-episode and unmedicated patients. However, the changes are modest (e.g. the difference in brain volume is about 3%), and with significant overlap between patients and controls. Furthermore, they are not diagnostically specific—for example, some findings are also seen in bipolar disorder (Arnone et al., 2009). There are few clear clinico-pathological associations, although particular structural alterations have been associated with specific symptoms and cognitive deficits—for example, thought disorder has been associated with smaller superior temporal gyri.

Table 11.12 Summary of structural brain changes in schizophrenia

As well as measuring volume, MRI methods are now available for assessing white matter pathways and connectivity between brain regions (e.g. diffusion tensor imaging). A range of abnormalities have been reported in schizophrenia, especially affecting the left frontal and temporal lobes (Ellison-Wright and Bullmore, 2009). Other MRI techniques have also identified differences in cortical thickness, surface area, and sulcogyral patterns.

Longitudinal studies have attempted to identify the course of structural brain changes in schizophrenia. The results are complex and controversial. Some changes are present before the onset of symptoms, while others emerge during the first episode (Smieskova et al., 2010). Thereafter there is some progression (Olabi et al., 2011), but the timing, magnitude, location, and cause remain unclear (Weinberger and McClure, 2002). For example, the extent to which the volume reductions are attributable to medication, and whether there are differences between atypical and typical antipsychotics in this respect, has not been established (Ho et al., 2011).

First-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia show changes in regional brain volumes that are intermediate between those of patients and unrelated healthy controls, which suggests that some of the brain abnormalities are associated with the genetic predisposition to the disorder (Boos et al., 2007).

Neuropathology

Post-mortem neuropathological studies have sought to explain the cellular and molecular basis for the neuroim-aging findings (see Table 11.12). For a review of this subject, see Harrison (1999) and Dorph-Petersen and Lewis (2011). A few findings deserve mention here.

• Brain weight is decreased by 2–3%.

• There is no evidence of any neurodegenerative processes. This supports a neurodevelopmental origin of the pathology, and also argues that any progression of pathology during the illness, as noted in some MRI studies, is not neurotoxic or degenerative in nature.

• The main positive histological findings are alterations in markers of synapses and dendrites, and in specific populations of neurons and glia. These changes, which are present in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus, suggest differences in synaptic connections, and have contributed to the ‘aberrant connectivity’ hypothesis of schizophrenia.

• An abnormal position or clustering of some neurons, notably in the entorhinal cortex and in the subcortical white matter, has been reported in several studies. Such findings are strongly suggestive of a prenatal abnormality in neuronal migration.

• Studies of gene expression have shown differences in families of genes consistent with the involvement of both neuronal and oligodendroglial cells in schizophrenia.

Note that virtually all of the patients whose brains were studied post mortem had been on medication. Therefore treatment may have contributed to the findings; indeed, some experimental data in non-human primates support this possibility.

Functional brain imaging