Learning disability (mental retardation)

Epidemiology of learning disability

Clinical features of learning disability

Physical disorders among people with learning disability

Psychiatric disorders among people with learning disability

Other clinical aspects of learning disability

Aetiology of learning disability

Assessment and classification of people with learning disability

The care of people with learning disability

Treatment of psychiatric disorder and behavioural problems

Ethical and legal issues in learning disability

Introduction

This chapter is concerned with a general outline of the features, epidemiology, and aetiology of learning disability (mental retardation), the organization of services and, more specifically, with the psychiatric disorders that affect these people. Many of the psychiatric problems of children with learning disability are similar to those of children of normal intelligence; an account of these problems is given in Chapter 22 on child psychiatry.

Terminology

Over the years, several terms have been applied to people with intellectual impairment from early life. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the word ‘idiot’ was used for people with severe intellectual impairment, and ‘imbecile’ for those with moderate impairment. The special study and care of such people was known as the field of mental deficiency. When these words came to carry stigma, they were replaced by the terms mental subnormality and mental retardation. The term mental handicap has also been widely used, but now the term learning disability is generally preferred in the UK (and is used in this chapter). However, the term mental retardation is still used in ICD-10 and DSM-IV, and is employed in many countries. Moreover, in the USA the term learning disability is generally applied to dyslexia and similar forms of specific disability, rather than to mental retardation. For this reason the alternative term intellectual disability is gaining acceptance.

The development of ideas about learning disability

A fundamental distinction has to be made between general intellectual impairment starting in early childhood (learning disability or mental retardation) and intellectual impairment developing later in life (dementia). In 1845, Esquirol made this distinction when he wrote:

Idiocy is not a disease, but a condition in which the intellectual faculties are never manifested, or have never been developed sufficiently to enable the idiot to acquire such an amount of knowledge as persons of his own age and placed in similar circumstances with himself are capable of receiving.

(Esquirol, 1845, pp. 446–7)

Early in the twentieth century, Binet’s tests of intelligence provided quantitative criteria for ascertaining the condition. These tests also made it possible to identify lesser degrees of the condition that might not be obvious otherwise (Binet and Simon, 1905). Unfortunately, it was widely assumed at the time that people with such lesser degrees of intellectual impairment were socially incompetent and required institutional care.

Similar views were reflected in the legislation of the time. For example, in England and Wales the Idiots Act of 1886 made a simple distinction between idiocy (more severe) and imbecility (less severe). In 1913, the Mental Deficiency Act added a third category for people who ‘from an early age display some permanent mental defect coupled with strong vicious or criminal propensities in which punishment has had little or no effect.’ As a result of this legislation, people of normal or near normal intelligence were admitted to hospital for long periods simply because their behaviour offended against the values of society. Although some of these people had committed crimes, others had not—for example, girls whose illegitimate pregnancies were interpreted as a sign of the ‘criminal’ propensities mentioned in the Act.

Although in the past the use of social criteria clearly led to abuse, it is unsatisfactory to define mental retardation in terms of intelligence alone. Social criteria must be included, since a distinction must be made between people who can lead a normal or near-normal life and those who cannot. DSM-IV defines mental retardation as a ‘significantly sub-average general intellectual functioning, that is accompanied by significant limitations in adaptive functioning in at least two of the following skill areas: communication, self-care, home living, social/ interpersonal skills used for community resources, self-direction, functional academic skills, work, leisure, health and safety’, and having an onset before the age of 18 years. Having defined the disorder in this way, it is subdivided by level of intelligence. In both ICD-10 and DSM-IV the subtypes are as follows: mild (IQ 50–70); moderate (IQ 35–49); severe (IQ 20–34); profound (IQ below 20). Acquired brain injury (ABI) is the term used to describe individuals who develop a learning disability after the age of 18 years (e.g. following a head injury).

The original World Health Organization (WHO) classification of impairment, disability, and handicap is useful when considering the problems of people with learning disability. (The WHO now employs a more positive terminology, with activity replacing ‘disability’, and participation replacing ‘handicap.’) The impairment is of the central nervous system, and the disability (or limitation of activity) is in learning and acquiring new skills. The extent to which impairment leads to disability (limits activity) depends, in part, on experiences in the family and at school, and on the correction of associated problems such as deafness. The final stage, namely handicap (or limited participation), depends on the degree of disability and on other factors such as the support that is provided.

Educationalists use other terms, and these differ between countries. In the UK, the term is special needs, whereas in the USA three groups are recognized—educable mentally retarded (EMR), trainable mentally retarded (TMR), and severely mentally retarded (SMR).

Epidemiology of learning disability

In 1929, in an important early survey, E. O. Lewis found that among schoolchildren in six areas of the UK the prevalence of mental retardation was 27 in 1000 children, and that of moderate and severe learning disability (IQ less than 50) was 3.7 in 1000. Subsequent studies have produced variable results, but a current estimate for the UK is 9–14 in 1000 children, and 3–8 in 1000 adults (Cooper and Smiley, 2009).

Variability in apparent prevalence rates is due partly to experimental factors such as methods of ascertainment and definition, but also reflects genuine differences in prevalence, and incidence, across time and place. In recent years, the incidence of severe learning disability has fallen substantially, because of the recognition of preventable prenatal and perinatal causes of learning disabilities. However, the prevalence has not fallen, and in fact is expected to rise by over 10% by 2020. The preserved or increasing prevalence despite reduced incidence reflects two factors. First, people with learning disability, particularly those with Down’s syndrome, are living longer. This has also affected the age distribution of people with severe learning disability, so that the numbers of adults have increased. Secondly, improvements in maternal and neonatal care are resulting in a growing number of children with learning disabilities, especially those in the severe and profound categories, who have survived significant events such as extreme prematurity.

A further important point regarding the prevalence of learning disability was made by Tizard (1964), who drew attention to the distinction between ‘administrative’ prevalence and ‘true’ prevalence. He defined the former as ‘the numbers for whom services would be required in a community which made provision for all who needed them.’ (In practice, the term usually means the number with needs who are known to the service providers.) It is estimated that less than 50% of all such people require special provision. Administrative prevalence is higher in lower socio-economic groups and in childhood when more patients need services. It falls after the age of 16 years because there is continuing slow intellectual development and gradual social adjustment.

The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in learning disability is covered later in the chapter.

Clinical features of learning disability

The most frequent manifestation of learning disability is uniformly low performance on all kinds of intellectual task, including learning, short-term memory, the use of concepts, and problem solving. Specific abnormalities may lead to particular difficulties. For example, lack of visuo-spatial skills may cause practical difficulties, such as inability to dress, or there may be disproportionate difficulties with language or social interaction, both of which are strongly associated with behaviour disorder. Among children with learning disability, the common behaviour problems of childhood tend to occur when they are older and more physically developed than children in the general population, and the problems last for longer. Such behaviour problems usually improve slowly as the child grows older, but may be replaced by problems that start in adulthood.

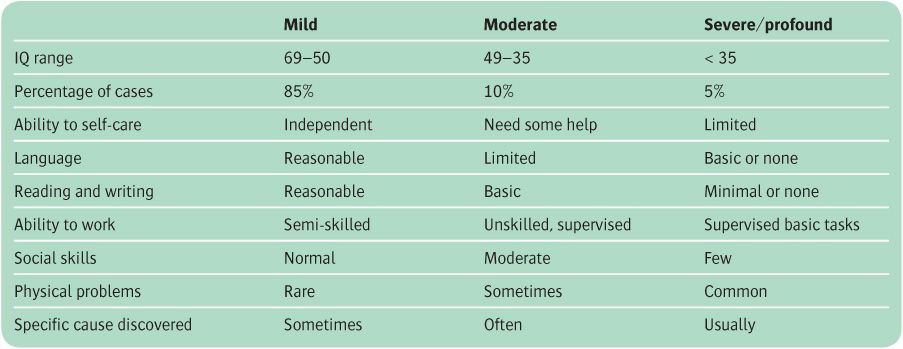

Learning disability is usually divided into three or four subtypes, which are defined by IQ (see Table 23.1). This classification is useful descriptively, and for understanding the epidemiology and aetiology of learning disability, as well as its management. The clinical features of the individual syndromes that cause learning disability are described later in the chapter.

Table 23.1 Features of mild, moderate, and severe/profound learning disability

Mild learning disability (IQ 50–70)

People with mild learning disability account for about 85% of those with learning disability. Usually their appearance is unremarkable and any sensory or motor deficits are slight. Most people in this group develop more or less normal language abilities and social behaviour during the preschool years, and their learning disability may never be formally identified. In adulthood, most people with mild learning disability can live independently in ordinary surroundings, although they may need help in coping with family responsibilities, housing, and employment, or when under unusual stress.

Moderate learning disability (IQ 35–49)

People in this group account for about 10% of those with learning disability. Many have better receptive than expressive language skills, which is a potent cause of frustration and behaviour problems. Speech is usually relatively simple, and is often better understood by people who know the patient well. Many make use of simplified signing systems such as Makaton sign language. Activities of daily living such as dressing, feeding, and attention to hygiene can be acquired over time, but other activities of daily living such as the use of money and road sense generally require support. Similarly, supported employment and residential provision are the rule.

Severe learning disability (IQ 20–34)

It is difficult to estimate IQ accurately when the score is below 34 because of the difficulty in administering the tests in a valid manner to individuals in this group. Estimates suggest that people with severe learning disability account for about 3–4% of the learning disabled. In the preschool years their development is usually greatly slowed. Eventually many of them can be helped to look after themselves under close supervision, and to communicate in a simple way—for example, by using objects of reference. As adults they can undertake simple tasks and engage in limited social activities, but they need supervision and a clear structure to their lives.

Profound learning disability (IQ below 20)

People in this group account for 1–2% of those with learning disability. Development across a range of domains tends to be around the level expected of a 12-month-old infant. Accordingly, people with profound learning disability are a vulnerable group who require considerable support and supervision, even for simple activities of daily living.

Physical disorders among people with learning disability

People with learning disabilities experience a greater variety and complexity of physical health problems than the rest of the population, but may not complain of feeling ill, nor be able to articulate their symptoms, and conditions may be noticed only because of changes in behaviour. Clinicians should be aware of the associations between certain learning disability syndromes and physical illness (e.g. Down’s syndrome; see p. 691), and that people with a learning disability are more likely to die prematurely (McGuigan et al., 1995). Learning disability also has an impact on physical health in ageing (Holland, 2000).

Sensory and motor disabilities and incontinence are the most important physical disorders in people with learning disability. People with severe learning disability (especially children) usually have one or often several of these problems. Only one-third are continent, ambulant, and without severe behaviour problems. Around 25% are highly dependent on other people. Among the people with mild learning disability, similar problems occur, but less frequently. Nevertheless, they are important because they determine whether special educational programmes are needed. Sensory disorders add an important additional obstacle to normal cognitive development. Motor disabilities include spasticity, ataxia, and athetosis. Ear infections and dental caries are common in this population.

Epilepsy is a frequent and clinically important problem in learning disability. Around 15–25% of people with learning disabilities have a history of epilepsy, compared with 5% in the general population. The prevalence increases with the severity of learning disabilities, with lifetime history of epilepsy estimated to be 7–15% in mild to moderate learning disability, 45–67% in severe learning disability, and up to 80% in profound learning disability. Epilepsy is more commonly associated with certain causes of learning disability, such as fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Angelman syndrome, and Rett syndrome, while certain epilepsy syndromes, such as West’s syndrome and Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, are more common among people with learning disability. The proportion of epilepsy cases that are drug-resistant is also greater among people with learning disability. Of particular concern is the incidence of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP), which is estimated to be 1 in 295 per year in the learning-disabled population, compared with 1 in 1000 per year in epilepsy patients in the general population.

For a review of the aetiology, diagnosis, and treatment of epilepsy in learning disability, see Iivanainen (2009).

Psychiatric disorders among people with learning disability

In the past, psychiatric disorder among the learning disabled was often viewed as different from that seen in people of normal intelligence. One view was that people with learning disability did not develop emotional disorders. Another view was that they developed these disorders, but that the causes were biological rather than psychosocial. It is now generally agreed that people with learning disability experience psychiatric disturbances similar to those which affect the general population. However, the symptoms are sometimes modified by low intelligence, and may not be easily recognized or communicated. Therefore, when diagnosing psychiatric disorder among people with learning disability, more emphasis may have to be given to behaviour and less to reports of mental phenomena than is usually the case.

For reviews of psychiatric disorders in learning disability, see Tonge (2009) and Dosen (2009), and for a review of their clinical assessment, see Holland (2009). Here we outline their epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Their assessment and treatment are covered later in the chapter.

Epidemiology and features of psychiatric disorder in people with learning disability

Among people with learning disability, published rates of psychiatric disorder vary widely, because of similar difficulties with case ascertainment, detection, and definition. Early studies primarily had the selection bias of including mainly people from institutions. Although more recent studies have included people from the community, it is difficult if not impossible to detect all adults with learning disabilities, particularly those with mild disability. The diagnostic criteria used in different studies have also varied—some used screening instruments, while others used structured diagnostic instruments. In addition, studies have varied in terms of whether they included behaviour disorders in the count of psychiatric disorders. Having noted these caveats, recent surveys report a prevalence of 16–45% among adults with learning disability (Cooper et al., 2007; Cooper and Smiley, 2009). There is less information about the incidence of psychiatric disorders, or their prevalence in children with learning disability. Specific disorders with higher rates in individuals with learning disability include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism, and dementia. Behavioural problems are also common, especially hyperactivity, stereotypies, and self-injury (Deb et al., 2001).

In general, the aetiology of psychiatric disorders in learning disability is thought to be similar to that in the general population. That is, they result from a complex and non-deterministic combination of biological, psychological, and social factors (see Chapter 5). Specific links between a learning disability syndrome and a psychiatric disorder (e.g. Down’s syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease) probably reflect a shared aetiological or pathological basis of the two conditions.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia affects 3–4% of people with learning disability, compared with less than 1% in the general population (Deb et al., 2001). The overlap between the two conditions largely reflects shared genetic factors. Clinically, delusions may be less elaborate than in patients with schizophrenia of normal intelligence, hallucinations may have a simpler content, and thought disorder is difficult to identify. When IQ is less than 45, it is difficult to make the diagnosis with any certainty. Furthermore, some of the symptoms of underlying brain damage, such as stereotyped movements and social withdrawal, may wrongly suggest schizophrenia, so a comparison of current with previous behaviour is always valuable.

The diagnosis of schizophrenia should be considered as one of several possibilities when intellectual or social functioning worsens without evidence of an organic cause, and especially if any new behaviour is odd and out of keeping. When there is continuing doubt, a trial of antipsychotic drugs is sometimes appropriate. The principles of treatment of schizophrenia in people with learning disability are the same as those for patients of normal intelligence (see Chapter 11).

Mood disorder

The rate of depressive disorders is comparable to, or slightly higher than, that of the general population (Deb et al., 2001; Tonge, 2009). However, people with learning disability are less likely than those of normal intelligence to complain of mood changes or to express depressive ideation. Diagnosis has to be made mainly on the basis of an appearance of sadness, changes in appetite and sleep, and behavioural changes of retardation or agitation. Severely depressed patients with adequate verbal abilities may describe hallucinations or delusions. Mania has to be diagnosed on the basis of hyperactivity and behavioural signs of excitement, irritability, or nervousness.

The differential diagnosis of mood disorder in people with learning disability includes thyroid dysfunction, which is especially prevalent in people with Down’s syndrome, and grief (Brickell and Munir, 2008).

The rate of suicide in people with moderate and more severe learning disabilities is lower than in the general population. The rate of deliberate self-harm is less certain, because it is difficult to decide the patient’s intentions and their knowledge of the likely effects of the injurious behaviour.

The principles of treatment of mood disorders are the same as those for people of normal intelligence (see Chapter 10).

Anxiety disorders and related conditions

Adjustment disorders are common among people with learning disability, occurring when there are changes in the routine of their lives. Anxiety disorders are also frequent, especially at times of stress. Obsessive–compulsive disorders are also found. Conversion and dissociative symptoms are sometimes florid, taking forms that can be interpreted in terms of the patient’s understanding of illness. Somatoform disorders and other causes of functional somatic symptoms can result in persistent requests for medical attention. Treatment is usually directed mainly to bringing about adjustments in the patient’s environment, and reassurance. Counselling, at an appropriate level of complexity, can also be helpful.

Eating disorders

Overeating and unusual dietary preferences are frequent among people with learning disability. Abnormal eating behaviours, including ‘pica’, are not uncommon (Grave-stock, 2003), but classical eating disorders appear to be less common than in the general population. Overeating and obesity are features of the Prader–Willi syndrome, a genetic cause of learning disability.

Personality disorder

Personality disorder occurs among people with learning disability, but is difficult to diagnose. In this population there is a considerable overlap between the diagnosis of behaviour disorder and that of personality disorder (Reid and Ballinger, 1987). Sometimes the personality disorder leads to greater problems in management than those caused by the learning disability itself. The general approach is as described on p. 704, although with more emphasis on finding an environment to match the patient’s temperament, and less on attempts to bring about change through self-understanding.

Delirium and dementia

Delirium. This may occur as a response to infection, medication, and other precipitating factors. As in people of normal intelligence, delirium in people with learning disability is more common in childhood and in old age than at other ages. Disturbed behaviour due to delirium is sometimes the first indication of physical illness. Delirium may also occur as a side-effect of drugs (especially anti-epileptics, antidepressants, and other psychotropic medication).

Dementia. As the life expectancy of people with learning disability increases, dementia in later life is becoming more common. Alzheimer’s disease is particularly common among people with Down’s syndrome (see p. 695), but dementia may also occur more commonly in other elderly learning-disabled people (Barcikowska et al., 1989). Dementia in people with learning disability may initially present with seizures, or with the usual progressive decline in intellectual and social functioning, which has to be distinguished from conditions such as depression and delirium.

Disorders that are usually first diagnosed in childhood and adolescence

Many of the disorders in this category are more frequent in children with learning disability than in the general population, and they are more likely to continue into adulthood. It is important to be aware that relatively specific developmental disorders of scholastic skills, speech, and language and motor function may occur alongside more global learning disability.

Autism and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Hyperactive behaviour and autistic-like behaviour are frequent symptoms of learning disability. In addition, the diagnoses of autism and ADHD are more common than among the general population. There is a particular comorbidity between learning disability and autistic spectrum disorders, probably reflecting an overlap in their aetiology, especially with regard to genetic factors (Matson and Shoemaker, 2009).

Abnormal movements

Stereotypes, mannerisms, and rhythmic movement disorders (including head banging and rocking) occur in about 40% of children and 20% of adults with severe learning disability. Repeated self-injurious behaviours are less common but important. There is a specific association with Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, in which the biting away of the corner of a lip is common. Prader–Willi syndrome is strongly associated with a pattern of self-injury where patients pick at their skin.

Challenging behaviour

The term challenging behaviour (or problem behaviour) is used to describe behaviour that is of an intensity or frequency sufficient to impair the physical safety of a person with learning disability, to pose a danger to others, or to make participation in the community difficult. It is probable that around 20% of learning-disabled children and adolescents and 15% of learning-disabled adults have some form of challenging behaviour. The causes of such behaviour are listed in Table 23.2. Whenever possible, the primary cause should be treated. Behavioural treatment (see p. 704) that is provided in the places where the behaviour most appears often or, in severe cases, in a residential unit, is sometimes helpful. For more information, see Emerson (1995) and Tonge (2009).

Sleep disorders

Serious sleep problems, such as obstructive sleep apnoea, excessive daytime sleepiness, and parasomnias, are not uncommon among people with learning disability and can be a source of considerable distress (Brylewski and Wiggs, 1998). Furthermore, sleep disorders may be associated with subsequent challenging behaviours and a worsening of cognitive impairment. The high rate of sleep disorders is accounted for by five factors:

• coexisting damage to CNS structures that are important for the sleep–wake cycle

• epileptic seizures that start during sleep

• epilepsy-related sleep instability that disrupts sleep architecture

• structural abnormalities in the upper respiratory tract causing sleep apnoea (particularly common among people with Down’s syndrome)

• poor sleep hygiene.

Treatment follows the usual principles of identifying and treating the cause, and improving sleep hygiene (see Chapter 14). Melatonin may have a role if medication is indicated (Braam et al., 2009).

Table 23.2 Causes of challenging behaviour

Forensic problems

People with mild learning disability have higher rates of criminal behaviour than the general population (see also Chapter 24, p. 712). The causes of this excess are multiple, but influences in the family and social environment are often important. Impulsivity, suggestibility, vulnerability to exploitation, and desire to please are other reasons for involvement in crime. Compared with the general population, learning-disabled people who commit offences are more likely to be detected and, once apprehended, may be more likely to confess. Among the more serious offences, arson and sexual offences (usually exhibitionism) are said to be particularly common.

Because people with learning disability may be suggestible and may give false confessions, particular care should be taken when questioning them about an alleged offence. In the UK, police interrogation should accord with the Police and Criminal Evidence Act, which requires the presence of an appropriate adult to ensure that the person with learning disability understands the situation and the questions. Once a learning-disabled person has been convicted, psychiatric supervision in specialized forensic learning disability units and specialized education may be needed.

Other clinical aspects of learning disability

Sex, relationships, and parenthood

Most people with learning disability develop sexual interests in the same way as other people. Yet although people with learning disability are encouraged to live as normally as possible in other ways, sexual expression is usually discouraged by parents and carers, and sexual feelings may not even be discussed.

In the past, sexual activity of people with learning disability was strongly discouraged because it was feared that they might produce disabled children. It is now known that many kinds of severe learning disability are not inherited, and that those which are inherited are often associated with infertility. Another concern is that people with learning disability will not be good parents. A study in Norway found that 40% of 126 children born to parents with learning disability suffered from ‘failures of care’ (Morch et al., 1997). However, some people with learning disability can care for a child successfully, so long as they are strongly supported.

It is especially important to consider issues of capacity and ability to consent to sexual relationships if a person with a learning disability becomes involved in such a relationship. These issues should be considered carefully in each case, and contraception made available where appropriate. Some learning disability teams run groups to help people with learning disabilities who wish to find a partner. Individuals in these groups are assessed carefully in order to create a safe environment, which is essential for those who are vulnerable.

Sexual problems

Some people with learning disability have a childlike curiosity about other people’s bodies, which can be misunderstood as sexual. Some expose themselves without fully understanding the significance of their actions. This is usually best dealt with by behavioural interventions or with specialized group therapy for those who are more able.

Maltreatment and abuse

Many children with learning disability are raised in families characterized by the factors that are associated in the general population with the maltreatment of children, but there is no convincing evidence that sexual or physical abuse is more frequent in families with a learning-disabled child. Instead, the sequelae of abuse are often found in people with learning disability who were brought up in an institution. When abuse has occurred, it may lead to psychological problems later in life which are similar to those experienced by any other victim of such abuse—for example, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (Sequiera et al., 2003). However, due to difficulty in emotional expression and communication, such disorders may present with challenging behaviours in situations with which the individual associates past abuse.

Growing old

Several problems arise more frequently as people with learning disability live longer, other than just the emergence of dementia and physical health problems (Hubert and Hollins, 2009). When the parents are the carers, they may find care increasingly burdensome as they grow old. Such parents are often concerned about the future of their learning-disabled child when they have died, yet are reluctant to arrange alternative care while they are still alive.

The older person with learning disability also faces special problems. If their parents die first, they face problems of bereavement. The isolation felt by many bereaved individuals may be increased because other people are not sure how to offer comfort, and because the learning-disabled person may be excluded from the ritual of mourning. These bereaved people should be helped to come to terms with the loss, using the principles that apply generally to grief counselling, but choosing appropriately simple forms of communication (Hollins and Esterhuyzen, 1997).

Effects of learning disability on the family

When a newborn child is found to be disabled, the parents are inevitably distressed. Feelings of rejection are common, but seldom last for long, and are replaced by feelings of loss of the hoped-for normal child. Frequently the diagnosis of learning disability is not made until after the first year of life, and the parents then have to make great changes in their hopes and expectations for the child. They often experience prolonged depression, guilt, shame, or anger, and have difficulty in coping with the many practical and financial problems. They also grieve for the intact child they had hoped and planned for. A few reject their children, some become overinvolved in their care, sacrificing other important aspects of family life, while others seek repeatedly for a cause to explain the learning disability. Most families eventually achieve a satisfactory adjustment, although the temptation to overindulge the child remains. However well they adjust psychologically, the parents are still faced with the prospect of prolonged hard work, frustration, and social problems. If the child also has a physical handicap, these problems are increased.

There have been several studies on the effect of a child’s learning disability on the family. In an influential study, Gath (1978) compared families who had a Down’s syndrome child at home and families with a normal child of the same age. She found that most families with a learning-disabled child had adjusted well and were providing a stable and enriching environment for their child(ren), although the other siblings were at some disadvantage because of the time and effort devoted to the disabled child. These findings have been supported by subsequent research. Teams specializing in services for children wit learning disability often offer a support service or support groups for siblings.

More recent studies have broadly confirmed the findings of Gath (1978), and have found that mothers with a learning-disabled child at home received help from their partner but little help from other people or services, and many professionals were seen by the parents as lacking interest and expertise. Financial difficulties are also common (Sloper and Beresford, 2006).

As the parents grow older, many fear for the future of their now adult disabled son or daughter. They need advice about ways in which they can arrange additional help when they become unable to provide the support that they gave when they were younger, and about ways of helping their son or daughter to remain in the family home after they have died.

For a review of the effects of learning disability on the family, see Gath and McCarthy (2009).

Aetiology of learning disability

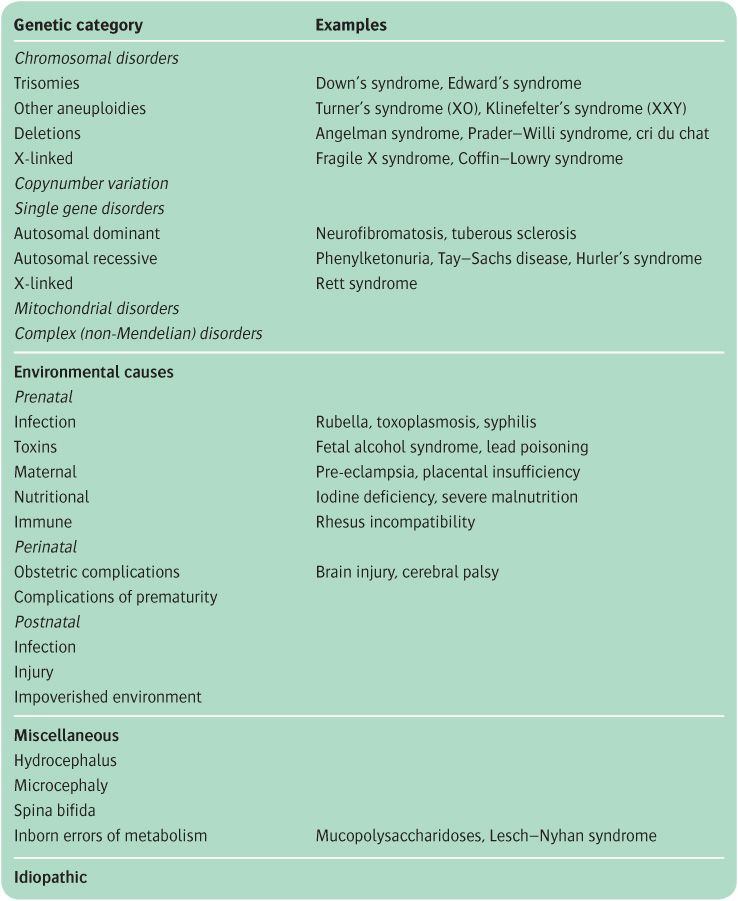

In a study of the 1280 mentally retarded people living in the Colchester Asylum, Penrose (1938) found that most cases were due not to a single cause but to a hypothesized interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors. This conclusion still broadly applies, especially for mild learning disability. Conversely, a specific cause for severe learning disability is often found. Table 23.3 lists the main categories of learning disability aetiology, and some examples of each.

Genetic factors are a major cause of learning disability. This is in part because intelligence is heritable (with estimates of around 30–50%; Deary et al., 2009), and learning disability is in this respect just the tail end of the normal distribution of intelligence in the population (indeed, by definition, 2% of people are expected to have an IQ of less than 70). This aspect of genetic predisposition to intelligence reflects the cumulative effects, and interactions, of a large number of genes, most of which have yet to be identified. In addition, a specific chromosomal or genetic defect can be the necessary and sufficient cause of a person’s learning difficulty. These include Down’s syndrome and fragile X syndrome, the two commonest causes of learning disability. This crude division of learning disability into cases where a specific cause can be found, and those where it reflects multiple, largely ‘non-specific’ causes, parallels the categorization into either ‘subcultural’ or ‘pathological’ mental retardation (as it was then called) made by Lewis (1929).

At a mechanistic level, the types of genetic abnormality that cause learning disability are diverse (see Box 23.1). The clinical features of the major genetic causes of learning disability are listed in Table 23.4, with additional details given in the text for Down’s syndrome and fragile X syndrome. For a review of the genetic causes of learning disability, see Ropers (2010).

Environmental factors are conveniently divided into pre-, peri- and postnatal factors, reflecting the time at which they are believed to have occurred. The relative importance of environmental factors varies according to setting. For example, they are more significant where healthcare provision or general health are poorer, and they may be affected by local factors (e.g. areas of low iodine predispose to congenital hypothyroidism). Social as well as biological factors should be considered in the environmental category. Even though the evidence remains inconclusive, it is notable that low intelligence is related to, and predicted by, psychosocial factors such as lower social class, poverty, and an unstable family environment (Sameroff et al., 1987). Some non-genetic causes of learning disability are summarized in Table 23.5.

Note also that aetiology of learning disability is sometimes defined in terms of an accompanying physical characteristic, such as hydrocephalus, microcephaly, or cerebral dysgenesis. Finally, the descriptive category of inborn errors of metabolism encompasses multiple different syndromes, mostly due to a single gene disorder affecting an enzyme that is important in a particular biochemical pathway. They include urea cycle disorders, and lysosomal storage disorders, which in turn include mucopolysaccharidoses (e.g. Hurler’s syndrome) and sphingolipidoses (e.g. Tay–Sachs disease), and others (e.g. phenylketonuria. For a review, see Kahler and Fahey (2003).

Overall, it is estimated that prenatal (genetic and environmental) factors cause 50–70% of learning disability, with 10–20% originating perinatally, and 5–10% originating postnatally; the proportions, and the causes within each category, depend on the population being studied. For reviews of the aetiology of learning disability, see Clarke and Deb (2009), Kaski (2009), and Tonge (2009).

Down’s syndrome

In 1866, Langdon Down tried to relate the appearance of certain groups of patients to the physical features of ethnic groups. One of his groups had the condition originally called mongolism, and now generally known as Down’s syndrome. This condition is a frequent cause of learning disability, occurring in 1 in about every 650 live births. It is more frequent among older women, occurring in about 1 in 2000 live births to mothers aged 20–25 years, and 1 in 30 live births to those aged 45 years. The incidence of Down’s syndrome has decreased because of increased rates of detection of the condition by amniocentesis and subsequent termination of pregnancy.

Table 23.3 The types of causes of learning disability

The clinical picture consists of a number of features, any one of which can occur in a normal person. Four features together are generally accepted as strong evidence for the syndrome. The most characteristic signs are listed in Table 23.6. IQ is generally between 20 and 50, but in 15% of individuals it is above 50. Mental abilities usually develop fairly quickly in the first 6 months to a year of life, but then increase more slowly. Children with Down’s syndrome are often described as loveable and easygoing, but there is wide individual variation. Emotional and behaviour problems are less frequent than in forms of retardation associated with clinically detectable brain damage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree