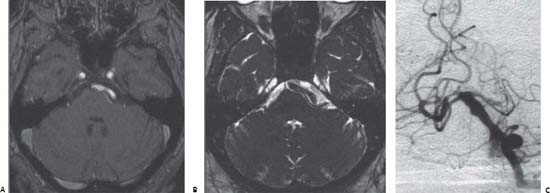

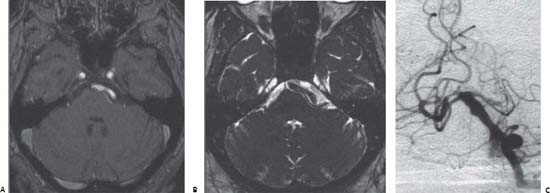

Case 74 Hemifacial Spasm and Microvascular Decompression Bassem Sheikh Fig. 74.1 T2-weighted magnetic resonance image at the level of the posterior fossa. Fig. 74.2 (A) T1- and (B) T2-weighted magnetic resonance images at the level of the posterior fossa and cerebellopontine angle. (C) Vertebral digital subtraction angiography of the same patient.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Questions

Questions

Answers

Answers

74 Hemifacial Spasm and Microvascular Decompression

Case 74 Hemifacial Spasm and Microvascular Decompression Fig. 74.1 T2-weighted magnetic resonance image at the level of the posterior fossa. Fig. 74.2 (A) T1- and (B) T2-weighted magnetic resonance images at the level of the posterior fossa and cerebellopontine angle. (C) Vertebral digital subtraction angiography of the same patient.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Questions

Questions

Answers

Answers

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree