CHAPTER 90 Ablative Surgery for Spasticity

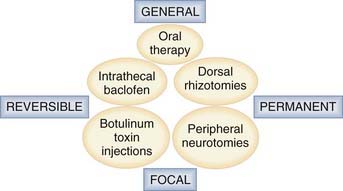

Management of spasticity includes not only intrathecal baclofen therapy and botulinum toxin injections but also destructive surgery directed at peripheral nerves, dorsal roots, the dorsal root entry zone (DREZ), and the spinal cord. Methods of surgical management are classified according to whether their impact is general or focal and whether the effects are temporary or permanent (Fig. 90-1).

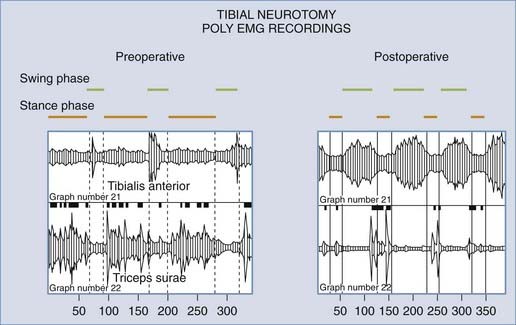

Neurodestructive procedures must be performed so that excessive tone is reduced without suppressing useful muscular tone or impairing any residual motor/sensory functions. In patients who retain some masked voluntary motility, the aim is to re-equilibrate the balance between paretic agonist and spastic antagonist muscles so that treatment results in improvement in (or the reappearance of) voluntary motor function (Fig. 90-2). In patients with poor residual function preoperatively, the aim is to halt the evolution of orthopedic deformities and improve comfort.

Our team has treated more than 1000 patients with spasticity over the past 20 years. We believe that teams dealing with spasticity should have all of the technical modalities at hand.1 Intrathecal baclofen therapy, which is discussed in detail in another chapter of this book, is indicated primarily for paraplegic or tetraplegic adult patients with diffuse spasticity, especially of spinal origin, although it can also be used to treat spasticity related to cerebral palsy in older children. Ablative operations are indicated for focal spasticity of the limbs when treatment with botulinum toxin injections proves insufficient. Peripheral neurotomy is justified when harmful spasticity affects one or a few muscular groups. A preliminary test consisting of an anesthetic block may help in the decision-making process by mimicking the effect of the neurotomy. When harmful spasticity affects an entire limb or in the setting of hemiplegia or paraplegia, surgery directed at the dorsal roots (dorsal rhizotomy) or the DREZ (microsurgical DREZotomy) may be the solution. Complementary orthopedic operations are frequently needed in patients with associated irreducible contractures, tendon retractions, joint deformities, or any combination of these problems.

Selective Peripheral Neurotomy

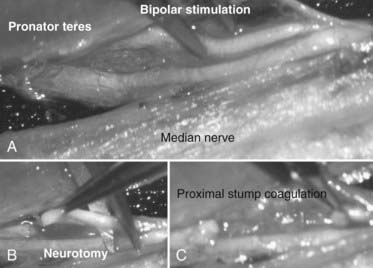

Peripheral neurotomy was introduced for the treatment of a spastic foot by Stoffel.2 Later, peripheral neurotomy was made more selective by using microsurgery and mapping via intraoperative electrical stimulation to better identify the function of individual nerve fascicles (Fig. 90-3).3,4 Neurotomy consists of partial sectioning of one or several of the motor branches (or fascicles) corresponding to the muscle or muscles in which spasticity is considered excessive and works by interrupting the segmental reflex arc in both its afferent and efferent limbs. Neurotomy must not include sensory nerve fibers because even partial sectioning of them can result in deafferentation pain. Either motor branches must be clearly isolated from the nerve trunk, or the fascicles must be dissected and identified within the nerve trunk several centimeters proximal to the formation of an identifiable branch. On an empirical basis it is agreed that neurotomy must include sectioning of approximately 50% to 80% of all the branches to a targeted muscle for it to be effective.

Surgical Techniques

Surgery on the Lower Limb*

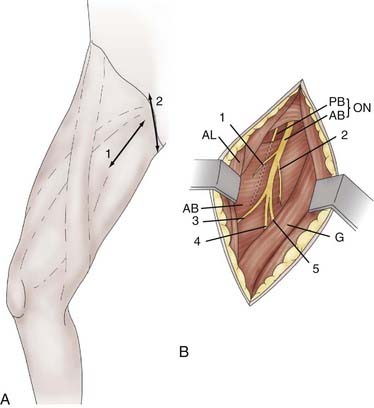

Obturator Neurotomy for the Hip

Obturator neurotomy eliminates spasticity of the adductor muscles. It is often proposed for diplegic children with cerebral palsy when crossing or “scissoring” of the lower limbs hampers their walking. It can also be performed on paraplegic children to facilitate perineal washing, toilet, and self-catheterization. The incision can be made along the body of the adductor longus at the proximal portion of the thigh or transverse in the hip flexion fold, centered on the prominence of the adductor longus tendon. In addition to its more aesthetic appearance, the latter incision facilitates adductor longus tenotomy when necessary (Fig. 90-4A). The dissection is conducted lateral to the adductor longus muscle body to rapidly locate the anterior branch of the obturator nerve. The posterior branch is situated more deeply and should be spared to preserve the hip-stabilizing muscles (Fig. 90-4B).

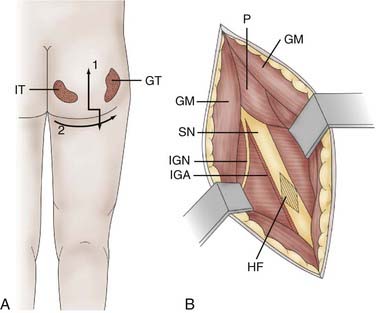

Hamstring Neurotomy for the Knee

Hamstring neurotomy is indicated for children with spastic diplegia to counter the accentuation of flexion deformity of the knees observed with growth. A transverse incision is made in the gluteal fold, centered on the groove between the ischium and greater trochanter (Fig. 90-5A). After crossing the fibers of the gluteus maximus, the sciatic nerve is identified in the depth of the incision. Branches to the hamstring muscles are isolated at the border of the nerve, primarily based on motor evoked responses of the semitendinosus muscle, which is often the major muscle responsible for spasticity (Fig. 90-5B).

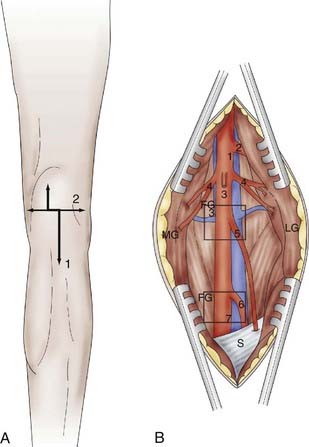

Tibial Neurotomy for the Foot

Tibial neurotomy is indicated for the treatment of varus spastic footdrop with or without claw toes. It consists of exposing all motor branches of the tibial nerve at the popliteal fossa (i.e., nerves to the gastrocnemius and soleus, tibialis posterior, popliteus, flexor hallucis longus, and flexor digitorum longus). In a majority of patients, the soleus is almost completely responsible for the pathogenesis of spastic footdrop, so the gastrocnemius may be spared.8 The incision can be made vertical on either side of the popliteal fold and extended inferiorly or transversely in the popliteal fossa to yield a more aesthetic result. In addition, the latter incision allows high tenotomy of the gastrocnemius fascial insertion to be performed at the end of the procedure if necessary (Fig. 90-6A).

The first nerve encountered is the sensory medial cutaneous nerve of the leg, which is located immediately anterior to the saphenous vein. It must be spared. More deeply, the tibial nerve trunk, from which the nerves to the gastrocnemius emerge, is easily identifiable. The superior soleus nerve is situated in the midline, just posterior to the tibial nerve. An effective soleus neurotomy is marked by the immediate intraoperative disappearance of ankle clonus. By retracting the tibial nerve trunk medially with a traction adhesive tape, the other branches can then be identified by electrical stimulation as they emerge from the lateral edge of the tibial nerve trunk. The most lateral branch is the popliteal nerve, followed by the tibialis posterior nerve and finally by the inferior soleus nerve and flexor digitorum longus nerves. Some fascicles, often larger, can give a toe flexion response via the intrinsic toe flexors (Fig. 90-6B). However, neurotomy of these branches is not recommended if they cannot be clearly individualized because they may be mixed with sensory fascicles.

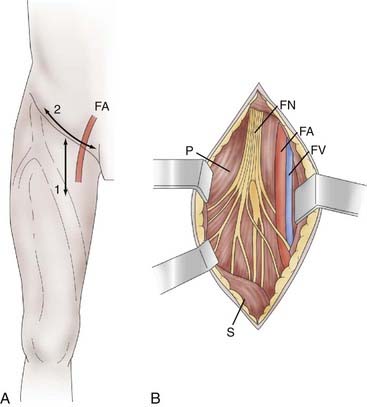

Femoral Neurotomy for the Quadriceps

Femoral neurotomy is indicated to treat excessive spasticity of the quadriceps muscle. This muscle is often spastic, which can interfere with gait by limiting knee flexion during the swing phase. Given its “strategic” importance in maintaining upright posture, a motor block is an essential part of the preoperative evaluation. The neurotomy involves the motor branch to the rectus femoris and vastus intermedius muscles. A horizontal incision is made in the hip flexion fold (Fig. 90-7A). The dissection passes medial to the sartorius muscle body and exposes the motor branches of the femoral nerve, first the nerve to the rectus femoris and then, more deeply, the nerve to the vastus intermedius (Fig. 90-7B). Electrical stimulation is essential given the large number of sensory fascicles of this nerve that must be spared.

Surgery on the Upper Limb

Pectoralis Major and Teres Major Neurotomy for the Shoulder

Neurotomy of collateral branches of the brachial plexus innervating the pectoralis major or the teres major is indicated for spasticity of the shoulder with internal rotation and adduction.9 For the pectoralis major, the skin incision is made at the innermost part of the deltopectoral sulcus and curves along the clavicular axis. The clavipectoralis fascia is then opened and the upper border of the pectoralis major muscle reflected downward. Close to the thoracoacromialis artery, the ansa of the pectoralis muscle is identified with the aid of a nerve stimulator. For the teres major, the skin incision follows the inner border of the teres major from the lower border of the posterior head of the deltoid muscle to the lower portion of the scapula. The lower border of the long portion of the brachii triceps constitutes the upper limit of the approach. The dissection is carried deep between the teres minor and major muscles. In the vicinity of the subscapular artery, the nerve ending on the teres major is identified. The nerve is surrounded by thick fat when approaching the anterior facet of the muscle body.

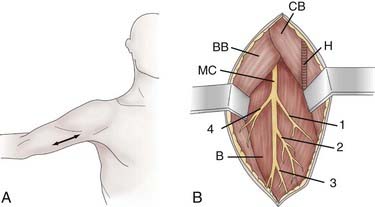

Musculocutaneous Neurotomy for the Elbow

Neurotomy of the musculocutaneous nerve is indicated for spasticity of the elbow with flexion mediated by the biceps brachii and brachialis muscles. The skin incision is performed longitudinally, from the inferior edge of the pectoralis major medial to the biceps brachii, and is extended 5 cm (Fig. 90-8A). The superficial fascia is opened between the biceps laterally and the coracobrachialis medially. The brachial artery and median nerve exit medially. The dissection proceeds in the space where the musculocutaneous nerve lies anterior to the brachialis muscle (Fig. 90-8B). Opening the epineurium allows the fascicles of the nerve to be dissected; the motor fascicles are distinguished from the sensory ones with a nerve stimulator.

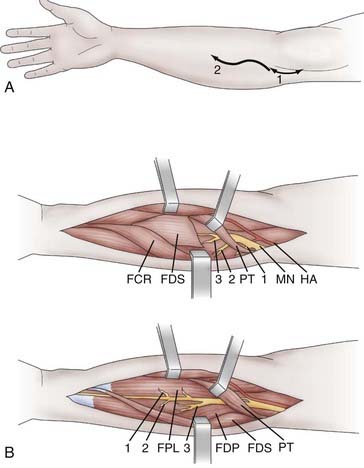

Median Neurotomy for the Wrist and Fingers

Neurotomy of the median nerve is indicated for spasticity of the forearm with pronation mediated by the pronator teres and quadratus muscle, for spasticity of the wrist with flexion mediated by the flexor carpi radialis and palmaris longus muscles, and for spasticity of the fingers with flexion attributable to the flexor digitorum superficialis (flexion of the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints) and the flexor digitorum profundus muscle (flexion of the distal interphalangeal joints). Swan neck deformation of the fingers mediated by the lumbrical and interosseous muscles can be limited by neurotomy of the median and ulnar nerves. With regard to the thumb, neurotomy of the median nerve is indicated for spasticity with flexion and adduction/flexion (thumb-in-palm deformity) attributable to the flexor pollicis longus. The skin incision begins 2 to 3 cm above the flexion line of the elbow, medial to the biceps brachii tendon, passes through the elbow, and curves toward the junction of the upper and middle thirds of the anterior aspect of the forearm (the convexity of the curve turns laterally) (Fig. 90-9A).10,11 Thereafter, the median nerve is searched for medial to the brachial artery and identified at the elbow, deeply under the lacertus fibrosus, which is cut. Sharp dissection is used to separate the branches of the median nerve. The pronator teres belly with its two heads is retracted medially and distally so that its muscular branches can be inspected. This muscle is next retracted up and laterally while the flexor carpi radialis is pulled down and medially. The muscular branches to the flexor carpi radialis and flexor digitorum superficialis can then be seen. Finally, the latter is retracted medially to uncover the branches to the flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, and pronator quadratus. These latter muscular branches may be individualized as separate branches or may remain together in the distal trunk of the anterior interosseous nerve. Sometimes it may be useful to divide the fibrous arch of the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle to make the dissection easier (Fig. 90-9B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree