Chapter 95 Adult Pseudotumor Cerebri Syndrome

Pseudotumor cerebri syndrome (PTCS) is characterized by (1) intracranial pressure (ICP) elevated to at least 250 mm H2O, (2) normal or small-sized ventricles, (3) no evidence of an intracranial mass, and (4) normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) composition. Most patients also have papilledema on funduscopic examination.1–3 About 10% of patients with PTCS have an identifiable cause for the condition; however, 90% of patients are young, obese women in whom no definite explanation can be found. Such individuals are said to have idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). As implied by the term “pseudotumor cerebri,” intracranial masses may present in a similar fashion. Patients with PTCS (including those with IIH) commonly present with headaches, tinnitus, horizontal diplopia, and progressive visual field defects. Headache, which is the most common symptom, is present in 94% patients and is dull in character and usually not localized.4 Diurnal variations in headaches with early morning aggravation are common. Straining and maneuvers like Valsalva that elevate ICP also exacerbate headaches. Lhermitte sign (electric shock-like neck pain precipitated by neck flexion) has also been reported.4,5 Pulsatile tinnitus is reported by up to 58% of patients.4 Visual deterioration in patients with IIH occurs almost exclusively in the setting of severe papilledema, beginning with enlargement of the physiologic blind spot and then progressing to nasal constriction, followed by temporal constriction, and, eventually, loss of central vision and color vision. As this occurs, the papilledema resolves, leaving optic atrophy and blindness. Transient visual obscurations occur in about 68% of patients and can be monocular or binocular. They usually occur at the peak of headache and are often precipitated upon bending or stooping.4 Metamorphopsia caused by distortion of the macula due to subretinal collections of fluid from a swollen optic disc usually occurs with very severe and chronic papilledema but may occur earlier in the course of IIH.6

Etiology and Causative Agents

Elevated dural venous pressures leading to disturbances in CSF absorption at the level of the arachnoid granulations is a widely proposed pathophysiology for IIH.7 Secondary intracranial hypertension as a cause of PTCS has been reported to occur following cerebral venous thrombosis in thrombophilic states, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE),8 protein C and protein S deficiencies,9,10 malignancies, oral contraceptive use,11 pregnancy, polycystic ovary disease,9 and from infections including meningitis and mastoiditis. Jugular valve insufficiency has also been found in association with PTCS/IIH.12 Thrombophlebitis due to an indwelling central venous catheter has also been reported to cause PTCS.13 Other associations with PTCS include metabolic and endocrine disturbances/conditions such as Addison disease, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, menarche, and pregnancy. A variety of drugs have been implicated in the development of PTCS, most commonly tetracycline, vitamin A, and lithium carbonate (Table 95-1).

Table 95-1 Causes of Pseudotumor Cerebri Syndrome

| Metabolic Disorders and Endocrinopathies |

| Pseudohypoparathyroidism |

| Hypophosphatasia |

| Prolonged corticosteroid therapy or too rapid corticosteroid withdrawal |

| Addison disease |

| Galactosemia |

| Pregnancy |

| Oral Contraceptives |

| Anabolic Steroids |

| Norplant System (Levonorgestrel Implants) |

| Drug Toxicities |

| Nalidixic acid |

| Doxycycline |

| Minocycline |

| Hypervitaminosis A |

| Lithium |

| Clomiphene |

| Venous Sinus Thrombosis and Elevated Central Venous Pressures |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome |

| Chronic otitis media and mastoiditis |

| Sinusitis |

| Jugular venous thrombosis |

| Thrombophilic States (Including Hematologic Disorders and Hyperestrogenic States) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) |

| Anemia |

| Iron deficiency anemia |

| Acquired aplastic anemia |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria |

| Megaloblastic anemia |

| Sickle cell disease |

| Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome |

| Other |

| Head injury |

| Sleep apnea |

Diagnosis

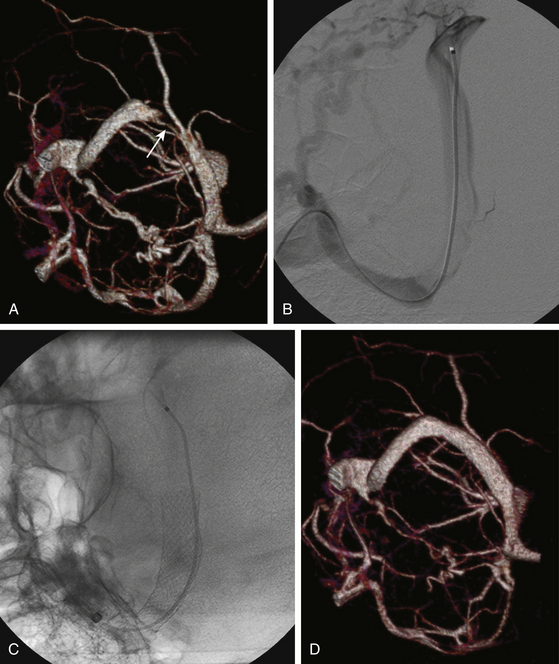

Patients who present with headaches with features suggestive of elevated ICP should undergo a funduscopic examination to assess the optic discs for papilledema. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomographic (CT) scanning should be performed in all patients with papilledema to evaluate for intracranial masses and to assess ventricular size. Patients with increased ICP may not only have normal or small-sized ventricles,14 but those with long-standing increased ICP may have an empty appearance of the sella turcica (26.7% sensitive, 94.6% specific), and patients with severe papilledema may show flattening of the posterior aspect of the eye (43.3% sensitive, 100% specific) (Fig. 95-1).15 The diagnosis of IIH thus should be suspected when no intracranial lesion is found and the ventricles are not dilated. In addition, MR or CT venography should be performed to determine if venous sinus stenosis or thrombosis is present, even if the patient appears to have a physical appearance typical of IIH. Neurologic examination in patients with PTCS/IIH usually reveals no focal deficits except for occasional unilateral or bilateral sixth nerve pareses.

A lumbar puncture to measure opening pressure and to assess CSF content is required to establish the diagnosis of PTCS/IIH. It is important however, that no patient undergoes lumbar puncture until an MRI or CT scan of the brain is performed to exclude an intracranial mass. CSF opening pressures greater than 250 mm H2O and normal CSF composition and cytology are required for diagnosis. Lumbar opening pressures should be always be measured with patients lying in the lateral decubitus position with legs extended and relaxed. Patients lying prone during the insertion of the LP needle should be repositioned to the lateral decubitus position before opening pressures are measured to prevent falsely high measurements that result from an increase in abdominal pressure when patients lie prone.1,3 This precaution should be observed especially when a lumbar drain is placed under fluoroscopic guidance during which patients are typically positioned prone. Similarly, patients whose lumbar puncture is performed with the patient sitting upright should be repositioned to the lateral decubitus position, as measurements of ICP in the sitting position are different from those in the lateral decubitus position, because of the relative positions of the heart and head.

Frequently, a single measurement of opening pressure and the presence of other clinical features fulfilling the criteria described above are sufficient to diagnose a patient with PTCS or IIH; however, patients with atypical presentations, such as chronic persistent headaches without papilledema and normal opening pressures, but in whom there is a high suspicion of IIH (obese patients or those with other conditions associated with IIH), require a 24- to 48-hour continuous recording of ICP, as intermittent elevations of ICP, mostly during sleep, can occur.16,17

Management

The treatment approach to patients of IIH is determined based on assessment of visual function. Weight loss, salt restriction, and analgesics for headaches should be recommended to patients with mild-to-moderate papilledema, but without any decrease in visual acuity or impairment of visual fields other than enlargement of the blind spot. Although weight loss is often difficult to achieve, it is clearly beneficial in attaining control of headaches and visual symptoms. Kupersmith et al. reported improvement in headaches and papilledema in 58 obese females with IIH who lost 7% to 10% of their weight over a 3-month period, and others have reported similar results with surgically produced weight loss.18,19 Acetazolamide should be initiated at doses of 250 mg QID or 500 mg (sequels) BID to lower ICP and decrease papilledema. Paresthesias, dizziness, dysgusia, and so on are common side effects of acetazolamide and may limit compliance or any increment in dose, particularly if patients are not warned about these effects before starting the drug. Visual function and fundus appearance should be monitored at regular intervals in all patients on medical treatment, so that any evidence of onset of progression of papilledema or development or progression of optic nerve dysfunction can be detected and treated with ONSF or shunt surgery. Patients with more severe papilledema or rapid decline in visual function should be monitored more frequently (e.g., every 1 to 2 weeks) than other patients. In such patients, the dose of acetazolamide may be increased up to 4 g/day. Some physicians are reluctant to use acetazolamide in patients with a sulfa allergy; however, this drug is not the same as typical sulfa drugs, and there is no evidence that patients allergic to sulfa drugs will have a similar allergic response to acetazolamide. For patients who cannot be treated with, cannot tolerate, or do not respond to acetazolamide, furosemide, triamterene or spironolactone may be used or added to the regimen. Topiramate is an antiepileptic agent that is being increasingly used in patients with IIH for its ability to lower ICP, reduce weight, and control headache, but its efficacy is not yet proven. A single open-label study reported equivalent visual field outcomes for topiramate and acetazolamide.32 Corticosteroids may be added to regimens of patients with autoimmune conditions such as sarcoidosis or SLE or in patients with recent venous sinus thrombosis; however, they have no place in the treatment of typical IIH and may, in fact, aggravate the condition by causing weight gain. In addition, withdrawal of steroids prescribed for other reasons has been associated with the development of PTCS.

In patients with moderate or severe papilledema who experience deterioration of visual acuity or worsening of their visual fields (other than enlargement of the blind spot) despite medical therapy or who cannot tolerate medical therapy, consideration should be given to more aggressive therapy. Surgical approaches to treatment of IIH include CSF diversion to lower ICP, ONSF, stenting of venous sinuses, and bariatric surgery for obese patients. Surgical treatment also should be considered in patients who are noncompliant with medications and in those with uncertain follow-up.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree