CHAPTER 287 Adult Thoracolumbar Scoliosis

Adult scoliosis is defined as any lateral curvature of the spine in a skeletally mature individual with a Cobb angle of greater than 10 degrees in the coronal plane, the lumbar and thoracolumbar levels most often being affected.1 Adult scoliosis can be further divided into two main types: type 1, or curves that develop de novo after skeletal maturity, and type 2, or curves that began before skeletal maturity.2,3 Although curves of the second type may be asymptomatic in children and adolescents, they often cause symptoms of pain, radiculopathy, or both in adults from continued progression of the curve and sagittal and coronal imbalance, even after skeletal maturity.3 Osteoporosis in an adult may hasten progression of the curve and the onset of symptoms. In addition to a thorough history and physical examination, the diagnostic work-up of a patient with symptomatic adult scoliosis includes static and dynamic plain radiographs, 36-inch standing scoliosis films, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) myelography, or any combination of these studies. Diskography, facet blocks, and epidural steroid injections may be used as ancillary tests to further correlate the clinical symptoms with radiographic abnormalities. The decision to initiate treatment is based mostly on evidence of continued curve progression and unrelieved pain. Cosmetic concerns are less often an indication for treatment in the general adult population, although they may become more important to young adults. Nonoperative management, including exercise, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, smoking cessation, and external bracing, is aimed at alleviating symptoms but does not prevent curve progression. The goals of surgical treatment are both elimination of symptoms and restoration of spinal balance. Surgical treatment of adult scoliosis has evolved tremendously within the past 30 years, mostly as a result of advancements in spinal instrumentation by Harrington, Dwyer, Luque, Zielke, Cotrel-Dubousset, and their colleagues.4–10 More recent advancements in segmental pedicle screw-rod fixation, as well as in anesthesia and perioperative care, have further improved surgical outcomes. This chapter discusses the diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes of patients with adult scoliosis with an emphasis on involvement of the thoracolumbar spine.

Classification and Etiology

Adult scoliosis is divided into two main types based on the timing of curve development relative to skeletal maturity.2

Type 1 (Primary Degenerative (De Novo) Scoliosis)

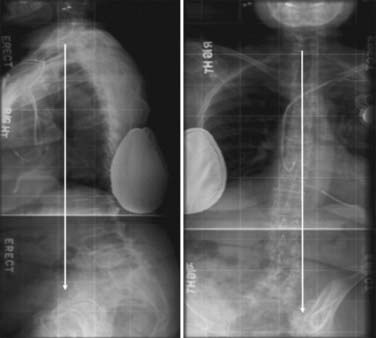

Primary degenerative, or de novo, scoliosis refers to adult scoliosis in which the curve develops in a previously straight spine after skeletal maturity and most often affects the lumbar and thoracolumbar spine. Type 1 includes scoliosis secondary to iatrogenic causes, vertebral fractures, degenerative changes, and osteoporotic disease.3 Type 1 adult scoliosis is the result of a spondylotic process in that it develops from asymmetrical degeneration of the intervertebral disk at one or more motion segments. A primary degenerative curve can also be referred to as a “diskogenic” curve.2 In addition, it can occur as a result of asymmetrical facet degeneration/hypertrophy. The asymmetrical degeneration of the intervertebral disk results in a coronal deviation with subsequent rotation of the vertebral body, which pivots on a facet joint.1 The apex of type 1 adult scoliosis curves is usually between L3 and L4, L2 and L3, or L1 and L2, in descending order of frequency. In general, de novo scoliotic curves have less of a coronal plane component than type 2, or progressive idiopathic scoliosis.11,12 Consequently, patients with primary degenerative adult scoliosis are usually affected by sagittal plane abnormalities secondary to lumbar hypolordosis or frank kyphosis (Fig. 287-1).13–16 Patients often have significant back or radicular pain (or both) as their chief complaint from this loss of normal sagittal balance. Because de novo scoliosis is primarily the result of a degenerative process, spinal stenosis from disk degeneration and facet hypertrophy is more common in these patients than in those with progressive idiopathic scoliosis.17,18

Type 2 (Progressive Idiopathic Scoliosis)

Progressive idiopathic scoliosis refers to scoliotic curves that began before skeletal maturity and includes idiopathic, congenital, and paralytic curves.3 Although idiopathic curves may be asymptomatic in children and adolescents, they often cause symptoms of pain, radiculopathy, or both in adults as a result of continued curve progression and sagittal and coronal imbalance, which occurs even after skeletal maturity (Fig. 287-2).3,19,20 In addition to pain, patients younger than 40 years have cosmetic concerns from progression of a (usually) thoracic curve.

Clinical Findings and Evaluation

Pain

Pain is the most common complaint of adults with scoliosis and is the deciding factor for surgical intervention in approximately 85% of such cases.3,14,21,22 The pain may be musculoskeletal or radicular in nature. Musculoskeletal back pain can be localized at the apex of the curve or at its concavity, and the areas above and below the curve may also be painful from excessive stress on the facet joints. This type of musculoskeletal pain is a result of both excessive strain and fatigue on the paravertebral muscles as they attempt to compensate for the loss of normal spinal balance, as well as a result of true spinal instability causing abnormal stress on the facet joints.2 Back pain is most often associated with loss of normal lumbar lordosis.23 Radicular pain is frequently encountered in patients with de novo scoliosis and is due to neural foraminal compression as a result of disk degeneration, bulging, and facet hypertrophy, especially on the concave side of the curve. Radicular pain may also be caused by traction of nerve roots on the convexity of the curve. Intercostal neuralgia secondary to rib cage deformity can be seen in patients with severe thoracic and thoracolumbar curves.3 The pain may be diffuse and constant in nature, or it may occur only with axial loading of the spine on standing. In the latter situation, the back and radicular pain is often relieved when recumbent because the spine, disks, facet joints, and neural foramina are unloaded.

The visual analogue scale should be used to quantify the severity of pain and is valuable in reporting changes in pain after treatment. The 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) is a validated outcome measure that can be used to determine the effects of not only pain but also the scoliotic condition in general on the patient’s physical and mental well-being. SF-36 scores have been found by several authors to be significantly lower in adult scoliosis patients than in controls.24,25

Neurogenic Claudication and Neurological Deficit

Neurogenic claudication secondary to lumbar stenosis often occurs in patients with primary degenerative scoliosis.26 Long thoracolumbar curves fused to shorter lumbar or lumbosacral curves can be associated with areas of severe canal stenosis at the transition zone and resultant claudicatory symptoms.2

Curve Progression

Progression of scoliotic curves can be manifested as changes in clothing size or height or frank alterations in body shape, such as a rib hump. Progression occurs in both adult degenerative and adult idiopathic scoliosis, although it has been found to occur more quickly in the latter group.19 Risk factors for lumbar curve progression include a Cobb angle of 30 degrees or greater, significant apical rotation, lateral listhesis of 6 mm or greater, and an intercrest line through or below the L4-5 disk space.27

Diagnostic Evaluation

History and Physical Examination

The physical examination should begin with a general inspection of the patient in the standing position with knees and hips fully extended (Fig. 287-3). The location and severity of spinal curves, rib humps, sagittal and coronal balance, pelvic obliquity, curve flexibility, and any leg length discrepancies should be noted. Moreover, an assessment of hip flexibility should be performed to rule out a hip contracture as the cause of the sagittal imbalance. Improvement in posture after sitting generally indicates a hip flexion contracture. The patient should also be examined in the supine position for evidence of improvement in sagittal and coronal alignment. A rigid thoracic kyphosis is usually indicated by the persistence of a kyphotic deformity in the supine position. A thorough neurological examination is performed to assess for abnormalities resulting from compression of nerve roots or the cord (or both). Gait and reflexes should be evaluated for evidence of myelopathy from thoracic canal stenosis. A left thoracic curve, toe clawing, asymmetrical abdominal reflexes, and gait/balance difficulties may indicate that syringomyelia, a tethered cord, or a neuromuscular syndrome is the primary abnormality, and treatment should subsequently be directed at these entities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree