27 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and its Variants

ALS is most often encountered as a sporadic, progressive, degenerative disorder of unknown etiology that characteristically affects both upper motor neurons (UMNs) and lower motor neurons (LMNs) and spares sensory and autonomic function. A small number of cases of ALS (approximately 10%) are familial and are discussed in Chapter 28. In addition, several variants of ALS are well recognized, including progressive bulbar palsy, progressive muscular atrophy (PMA), and primary lateral sclerosis (PLS). Other less common motor neuron disorders exist, including those with atypical motor neuron manifestations caused by genetic mutations, infections, and immunologic disorders (see Chapter 28). Because the prognosis in ALS is uniformly poor compared with other motor neuron disorders, it is essential that the correct diagnosis be reached.

Clinical

Progressive Bulbar Palsy

Patients with progressive bulbar palsy initially develop symptoms restricted to the bulbar muscles. They usually present with a several month history of progressive dysarthria with gagging, choking, and weight loss. The speech disturbance may lead to complete anarthria. These patients are commonly incorrectly diagnosed, and many undergo exhaustive ear, nose, and throat or gastrointestinal evaluations looking for the cause of dysarthria or dysphagia. Occasionally, patients may present with respiratory distress as the result of aspiration. Speech is most commonly slow and spastic with variable flaccid features, depending on the degree of LMN dysfunction. The tongue may be atrophied with fasciculations, accompanied by brisk jaw, gag, and facial reflexes (Figure 27–1). One of the characteristic signs is the “napkin or handkerchief sign.” Because of excessive drooling from bulbofacial weakness, patients often carry a tissue in their hand to frequently clear their mouth and face of saliva. Occasionally the symptoms remain relatively restricted to the bulbar muscles. However, in the vast majority of patients the disorder eventually progresses to involve the limbs, as in typical ALS. Indeed, approximately 25% of patients with ALS will have the bulbar onset form.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ALS usually is straightforward in patients who present with prominent UMN and LMN signs in both limb and bulbar muscles. However, most patients initially are seen early in the course of the disease, often when only one extremity is clinically affected. In addition, there are other disorders, some potentially treatable, which can mimic the clinical signs, electrophysiologic findings, or both in ALS and its variants (Box 27–1; also see Chapter 28). These disorders are discussed in detail later. In the case of classic ALS, the most important diagnosis to consider is coexistent cervical and lumbar stenosis. For PMA or predominantly LMN presentations of ALS, including the flail arm and flail leg syndromes, the most important diagnoses to consider are demyelinating motor neuropathy, especially MMNCB, and inclusion body myositis (IBM). In addition, benign fasciculation syndrome (BFS) and the myotonic disorders need to be kept in mind. In PLS, there is a large list of neurologic conditions that can be confused with the disorder and need to be excluded by appropriate imaging and other laboratory testing (see the section on Primary Lateral Sclerosis below).

Box 27–1

Differential Diagnosis of Motor Neuron Disease

Cervical/Lumbar Stenosis

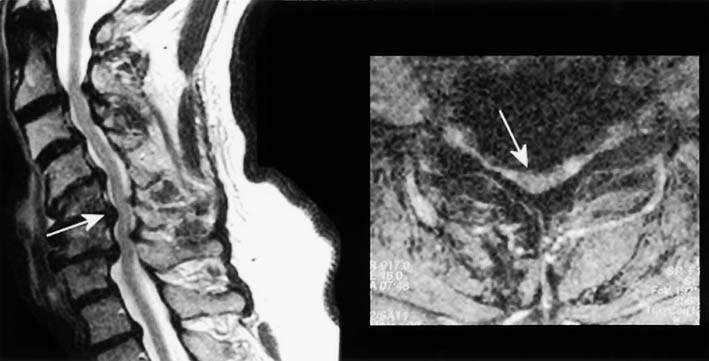

Degenerative disease of the neck and back is extremely common, especially in older individuals. The combination of cervical and lumbar spondylosis occasionally can mimic ALS, both clinically and in the EMG laboratory. Cervical spondylosis, by itself, is a common cause of gait disturbance in the elderly. Compression in the cervical area can result in a polyradiculopathy involving the cervical nerve roots as well as a myelopathy from direct cord compression. This can create a clinical picture of LMN dysfunction in the upper extremities and UMN dysfunction in the lower extremities (Figure 27–2). If additional compression occurs above the C5 level, UMN signs can be seen in the upper extremities as well. To complicate the situation further, patients with coexistent lumbar stenosis may have additional LMN signs in the lumbosacral myotomes. Taken together, the clinical picture can resemble ALS.

The signs and symptoms noted above will usually suggest the diagnosis of cervical and lumbar stenosis. However, occasionally a patient with cervical and lumbar stenosis presents with a relatively pure motor syndrome consisting of muscle weakness, atrophy, and spasticity, making the clinical distinction from ALS difficult. It is in these patients that the clinical and EMG evaluation of the bulbar and thoracic paraspinal muscles assumes special significance, because they should never be abnormal in lesions restricted to the cervical or lumbar spine (see Chapter 26).

Multifocal Motor Neuropathy with Conduction Block

An important condition that can mimic the PMA presentation of ALS clinically is demyelinating motor neuropathy. Nearly all peripheral neuropathies have both sensory and motor symptoms and signs; therefore, they are not frequently confused with ALS. Very few neuropathies, however, are purely or predominantly motor. Of those, most are demyelinating and are believed to be immune mediated. Although the exact pathophysiology is not understood, presumably some component of motor nerve or myelin is selectively targeted by the immune system, leading to motor dysfunction. It is in these circumstances that a motor neuropathy may be mistaken for a motor neuronopathy (i.e., motor neuron disease). Although it is quite rare, the motor neuropathy that must be excluded, especially in patients with predominantly LMN dysfunction, is MMNCB (see Chapter 26).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree