MRI diffusion-weighted imaging shows acute ischemia in the primary motor cortex and in neighboring white matter along the MCA–anterior cerebral artery (ACA) boundary zone (arrow).

These findings when taken together strongly imply that the patient experienced recurrent embolization from the highly irregular, ruptured plaque at the origin of the right ICA. The presence of irregular plaque is a well-established risk factor associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke recurrence [3]. This case also illustrates the very important relationship between TIAs or minor strokes and ischemic recurrence. Classically defined TIA has been known to predict stroke in about 10% of cases in the next 90 days, half of them within the next 48 hours [4]. A more recent effort to better define the fine structure of stroke recurrence following an initial minor ischemia demonstrated that 42% of strokes which would occur in the following 30 days occurred within the first 24 hours as our case clearly illustrates. Furthermore, these early recurrences frequently involve extracranial or intracranial large artery stroke [5,6].

Case 2. More carotid disease

A 67-year-old right-handed man was seen in neurologic outpatient consultation for recurrent spells. The first spell took place 2 months before the patient’s visit. Hospital reports indicated that there was an episode of near syncope followed by confusion. These records further indicated that the patient was transiently aphasic with aberrant behavior. The patient recalled only that he had been looking for his dog outdoors only to have neighbors discover and explain that his dog was in his trailer home. He also remembered failing to cover for his son at work as he had previously agreed to do. His recollection of the episode was limited and his recollection of the hospitalization was vague. MRI reportedly showed bilateral deep white matter changes. It was not clear if DWI was available at that site at that time. Carotid ultrasound study found left ICA stenosis estimated at between 50% and 79% with the detailed velocity data in the lower part of the velocity range. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed only mild mitral regurgitation and a normal ejection fraction. A 24-hour video EEG obtained during that hospitalization failed to show any epileptiform activity, The hospital discharge summary indicated that the patient had suffered either a TIA or mild stroke or possibly a seizure. The only medication added at discharge was clopidogrel.

His next medical encounter was initiated by a State policeman on a highway 2 months and 2000 miles distant from the initial event. The patient was detained after he was noted to be driving erratically on a highway. He was confused and initially thought to be intoxicated. He was brought to a local ED where he was evaluated and hospitalized. The ED staff as well as an evaluating neurologist initially thought the patient was intoxicated. He was confused but some aphasic features were noted by the examining neurologist. No blood alcohol was present. MRI of the brain again demonstrated bilateral deep white matter changes; however, DWI showed no restriction. An MR angiogram (MRA) of the head did suggest an asymmetry of flow, with less flow evident in the distal branches of the left MCA but the quality was such as to make that finding uncertain. The patient was maintained in the intensive care unit and monitored for 2 days. No arrhythmias were noted. A routine EEG did not show epileptiform activity. The patient enjoyed a good cognitive recovery and was discharged after 2 days of close observation. Clopidogrel was discontinued and warfarin added instead. The patient was discharged from the hospital and an outpatient consultation for our stroke clinic was arranged. When the patient was evaluated in the stroke clinic 2 weeks later, he was found to have no evidence of aphasia, normal mentation as well as a normal neurologic examination. The only abnormality noted was an occasional aberrant heartbeat not consistent with atrial fibrillation (AF). There were no cervical bruits. We noted that the patient was a retired commercial chemist who lived alone, had a motor home, and enjoyed traveling. His past medical history was significant for treated hypothyroidism, well-controlled hypertension treated with sustained release verapamil, cigarette smoking discontinued 25 years prior, and significant alcohol use discontinued 20 years prior. At the completion of that evaluation, 81 mg of aspirin daily was added. A 24-hour Holter monitor was requested with the understanding that should that monitor fail to demonstrate AF, warfarin would be discontinued. A repeat MRI brain and MRA of the head was also requested.

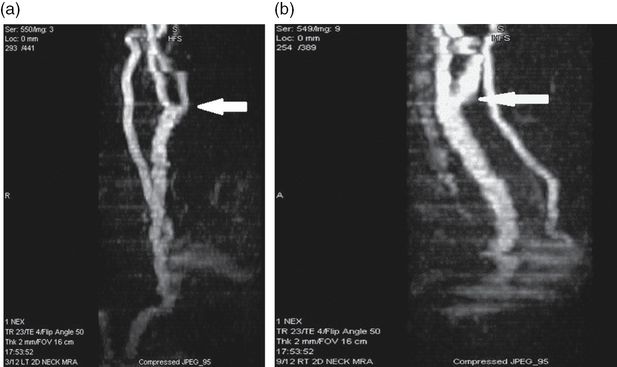

Several weeks later, the patient again experienced an aphasic or confusional episode. He telephoned the stroke clinic and was instructed to come to the clinic emergently. Examination at that time found the patient unable to perform complex tasks when verbally instructed to do so. He had difficulty with anything more than simple calculations. Mild word-finding difficulties, scattered neologisms, and some perseveration were noted. Speech production was slowed. A mild right hemi-apraxia was noted. Immediate recall was impaired. The patient was able to give a partial history. He realized he was having difficulties but could not define them precisely. He did recall having a great deal of difficulty dialing the number to the stroke clinic but he drove there uneventfully. The patient was immediately admitted to hospital. There, he was evaluated by a neurology resident who found his speech was slurred. The patient was mistaken as to the year and when asked to name the current president, he erroneously named the prior president instead. There was no weakness and no sensory deficit. The Neurology Resident felt the patient was perhaps intoxicated with something other than alcohol; however, a toxicology screen was negative. Within several hours, the patient’s primarily left hemispheric deficits fully resolved. An EEG was obtained that day. Cerebral activity was described as diffusely slow, with 5–6 Hz predominance and an excess of bifrontal delta activity but again no epileptiform activity was noted. MRI of the brain again showed no diffusion restriction. MR T2 FLAIR sequences showed bilateral periventricular and juxtacortical white matter changes, more pronounced on the left than on the right (Figure 6.4). MRA of the head showed no definite abnormalities. MRA of the neck showed only minor changes suggestive of carotid bifurcation atherosclerosis with minimal stenosis on the left (Figure 6.5). Cardiac monitoring failed to show any evidence of AF. A catheter angiogram was proposed to the patient but he declined. The patient was discharged on aspirin and lamotrigine and warfarin was discontinued. The patient reported another confusional episode several weeks later, he was evaluated in the ED, and lamotrigine dose was increased. Subsequently, he agreed to a catheter cerebral angiogram (Figure 6.6). The biplane cerebral angiogram demonstrated a very large, severely ulcerated plaque at the left ICA origin with about 60% stenosis measured in the most affected plane. After some debate between stroke specialists and an epileptologist, a left carotid endarterectomy (CEA) was recommended. Following uneventful CEA, lamotrigine was weaned over 3 months and the patient was event free for at least 7 months. He was lost to follow-up after he resumed his highway travels.

MR T2 FLAIR image demonstrating a large asymmetry in juxtacortical and corona radiata T2 bright signal which is considerably greater on the left (arrow).

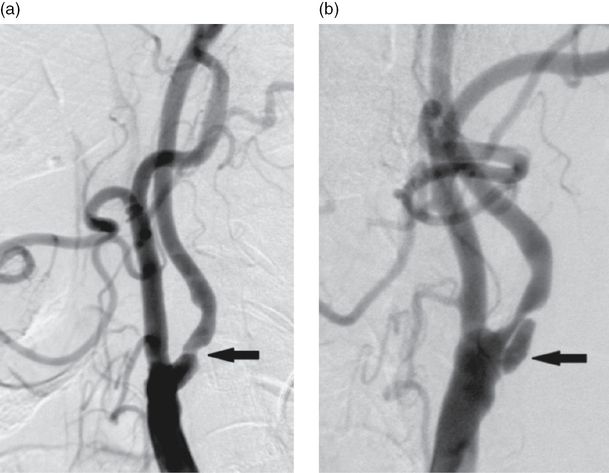

Catheter angiogram left common carotid artery injection with two orthogonal views. Arrows indicate the carotid bifurcation. A deep, elongated unusually large ulceration is well seen in image b (arrow) but is not even suspected in image a, which only shows what appears to be smooth plaque and at most moderate stenosis.

Lessons to be learned in this case are many. The most elementary are to be very circumspect about placing a patient on therapy for tentative diagnoses. The patient was placed on warfarin for a time although AF or other adequate indication had not been demonstrated. It is worthwhile noting that prolonged highly portable ECG recording (for example a 30-day event monitor) was not available at the time of this case presentation. Although epilepsy can be an elusive diagnosis, this patient had repeated normal EEG recordings including a full day of video continuous EEG monitoring, so making that diagnosis could be at best only tentative. Conventional ultrasound and conventional cervical MRA will on occasion fail to find significant atherosclerotic disease at the carotid bifurcations as this case strikingly demonstrated. Advanced multi-detector CTA, high resolution ultrasonography, or as in this case catheter angiography are remedies. Repeated carotid embolism would reasonably be expected to demonstrate MR diffusion restriction if timely images, within 1 week, are obtained but this is not always the case. Rigorous clinically defined TIA may fail to show diffusion restriction at least 50% of the time. Atherosclerotic carotid plaque with ulceration is notably associated with high risk of recurrent ischemic events [7,8]. Although recurrent carotid ischemia can be devastating as in Case 1, on some occasions it can be somewhat subtle, as in this case. This patient’s lesion had a very unusual appearance which may correlate with the unusually elusive clinical presentation. In general, symptomatic ICA disease carries a very high risk of early recurrence and should be treated promptly [9].

Case 3. Intracranial atherosclerosis

A 94-year-old man was doing relatively well, living alone and managing most of his own affairs successfully, when he developed abrupt weakness which he described as a “ball and chain” suddenly fastened to his right leg. He also felt shortness of breath and thought that he might have some bilateral lower extremity weakness as well. He had two such episodes. The first lasted 1 hour, resolved completely and about which he chose to do nothing. The second episode the following morning he found sufficiently alarming that he called for emergent medical assistance. His weakness completely resolved by the time he reached the ED of our hospital.

Past medical history included arterial hypertension, hypothyroidism, chronic mild macrocytic anemia, benign prostate hypertrophy, and peripheral vascular disease. His peripheral vascular disease never progressed to the point of requiring intervention. Similarly, he had known, mild to moderate asymptomatic cervical carotid and subclavian atherosclerotic disease which had been followed by ultrasound studies for the prior 7 years and had not required intervention.

Examination in the ED demonstrated no neurologic deficits. CT scan of the brain showed bilateral periventricular white matter changes but no discrete infarcts. The patient was diagnosed with either TIA or transient orthostatic hypotension. He received intravenous (IV) fluids and mild systolic hypotension was soon replaced by isolated systolic hypertension with relatively wide pulse pressure. The neurologic consultant recommended an MRI of the brain, which showed no acute diffusion restrictions. That study did demonstrate bilateral periventricular and juxtacortical white matter changes as well as changes in the pons consistent with small vessel vasculopathy. Carotid ultrasound studies were repeated and were read out as showing bilaterally 50–69% ICA stenosis with heterogeneous plaque. These ultrasound results were little changed from studies performed 2 and 7 years prior. The patient had subjective orthostatic symptoms which resolved spontaneously. Lipid profile demonstrated a total cholesterol of 121 mg/dL, an HDL of 57 mg/dL and a calculated LDL of 60 mg/dL. Repeated ECGs showed sinus rhythm or mild sinus bradycardia with few premature atrial complexes. He was discharged home the following morning on his previous medications which included 325 mg of aspirin daily, lisinopril with hydrochlorothiazide, levothyroxine, and tamsulosin.

Five days later the patient was readmitted to hospital after experiencing transient right lower extremity weakness again. He had fallen twice while at home but without significant injury. Mild, transient systolic hypertension was again noted in the ED. Fluids were again given. The patient’s neurologic examination was considered normal, unchanged. He was admitted for further investigation and physical therapy. The ED physician and internists expected placement would be necessary at discharge as it was doubted that the man could continue to live independently. Peripheral vascular studies were repeated which showed no significant change. A plain radiograph of the knee showed a subacute to chronic fracture of the medial femoral condyle on the right. Echocardiography demonstrated a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60% and mild diastolic dysfunction. On the third hospital day the patient was transferred to the rehabilitation service.

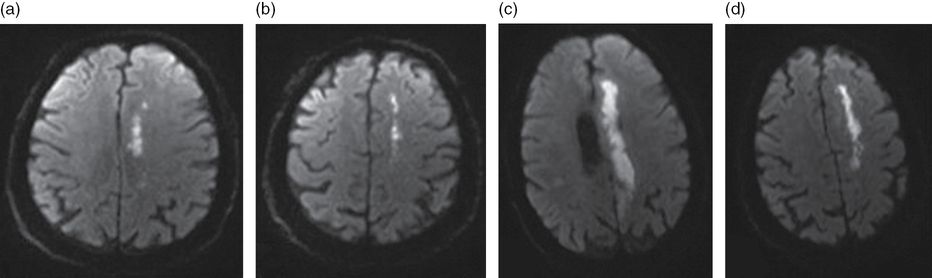

The following day, in mid-afternoon, the patient was noted to be less responsive, with right-sided weakness and language difficulties. An acute stroke code was initiated. Examination demonstrated mild aphasia and significant right-sided weakness as well as right gaze preference with an NIHSS score of 11. CT scan demonstrated no other bleeding or signs of acute infarction. The patient did not receive acute thrombolytic therapy because time of onset was uncertain. He was last seen well 3½ hours before his deficits were recognized. The patient was subsequently transferred to the neurology service. MRI of the brain demonstrated ischemic changes involving the territory of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) on the left (Figure 6.7). MRA of the head was obtained and this was read out as showing minor intracranial atherosclerosis and otherwise unremarkable (Figure 6.8). The patient was judged to have moderate symptomatic stenosis of the left ICA origin, carotid artery endarterectomy was tentatively offered but the patient and family declined. The patient was placed on atorvastatin. Aspirin was substituted with clopidogrel. The patient made a good recovery with respect to language and right upper extremity function, but his right lower extremity remained weak. He was discharged to a skilled nursing facility for further rehabilitation 2 days after his acute stroke.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to hospital. Over the prior 10 days he had developed increasing confusion, difficulties with speech, and increased right-sided weakness. A urinary tract infection was diagnosed and treated. The patient was relatively hypotensive with significant pre-renal azotemia and hypernatremia. Dehydration was diagnosed and treated. A repeat MRI of the brain demonstrated new ischemia (Figure 6.9). MRA of the head was repeated (Figure 6.10) and MRA of the neck was obtained. Neurologically, the patient was arousable but unable to speak clearly. He could follow simple commands with effort. He was noted to have increased motor tone throughout with significant right-sided weakness. Fluid resuscitation reversed the patient’s renal failure and hyponatremia. There were no further signs of infection. Despite these treatments, his cognitive status further declined. After discussion with family, comfort care was elected. The patient was transferred to a skilled nursing facility for hospice care and died several days later.

MR DWI showing ACA territory and ACA/MCA boundary zone ischemia of the initial stroke (a and b) and new, larger DWI lesions in the same distribution exactly 2 weeks later (c and d).

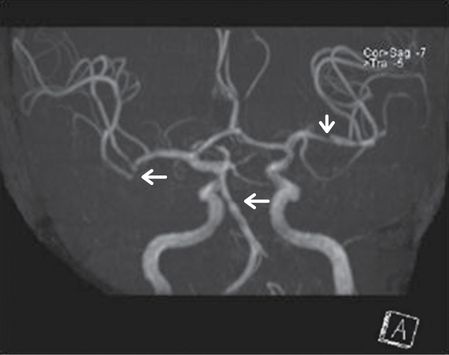

MRA MIP projection left intracranial ICA shows cutoff of the pericallosal branch of left ACA (horizontal arrow) and diminished flow in the proximal segment of the neighboring fronto-polar branch (vertical arrow). The right ACA (immediately above left ACA) appears artifactually discontinuous in this projection.

The pitfalls in this case are many. Evaluating the very elderly patient clinically is complex and involves consideration of many comorbidities and competing possibilities. When our patient was initially admitted with TIA considered likely, vascular imaging other than repeated carotid ultrasound studies was not obtained. Carotid ultrasound studies alone are often obtained with the idea that should symptomatic and sufficiently severe stenosis be demonstrated, effective intervention is possible or at least should not be overlooked. The value of this approach in a nonagenarian is far from clear. In general and regardless of age, comprehensive vascular imaging should be obtained in any TIA patient in the hopes of elucidating the likely origin of the patient’s ischemic symptoms and in selecting the most appropriate care.

This patient’s primary problem was multiple intracranial atherosclerotic stenoses. Long recognized as an important cause of ischemic stroke in patients of non-European origin with a prevalence as high as 50% in stroke patients from China or Japan, symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis with a prevalence as high as 10–20% is now recognized in stroke patients of European origin [10,11]. Like other stroke etiologies, the frequency of intracranial atherosclerosis increases significantly with age. When MRA of the head is obtained, it is important to personally review the projection images and source images carefully while bearing in mind MR diffusion and T2 FLAIR imaging results and correlate them. In this instance, these considerations would have led to the discovery of subtle but clear-cut evidence of the absence of a major branch of the A2 segment of the left ACA (Figure 6.10) as well as clinically important distal left MCA stenosis (Figure 6.8). These findings best explain the recurrent left ACA stroke and MCA/ACA border zone infarct pattern.

A reduction in antihypertensive medications, the early addition of a statin, and an understanding of the critical importance of good hydration might have altered outcome in this patient, at least in the short run. It is common clinical practice to augment or alter antiplatelet therapy in the setting of recurrent TIA or recurrent stroke. Although this practice may not be well supported by evidence-based reasoning in many instances, the brief use of dual antiplatelet therapy may arguably have been helpful in this case. It is important to exercise considerable caution when assigning stroke etiology based on carotid ultrasound data alone. In this case, careful review of serial carotid ultrasound studies showed that peak proximal and mid internal carotid artery velocities were variable between studies and did not show progression overall. An analysis of cervical MR angiography which in this case was marred by movement demonstrates marked tortuosity of the left internal carotid artery origin and fails to confirm the ultrasound estimate of stenosis. Discordant results with respect to degree of carotid artery stenosis when different imaging modalities are compared is not uncommon [12]. Surgical treatment of symptomatic, mild carotid artery origin disease may not be appropriate for all patients, particularly where life expectancy is limited [13]. In this instance, carotid disease contributed little to overall ischemic risk. Good decision-making requires consideration of all the data, cognizance of applicable treatment guidelines, and most importantly, consideration of the characteristics of the individual patient.

Recurrent stroke due to intracranial atherosclerosis in the same arterial distribution is common, noted in over 12% of patients radiologically and in 4% of patients clinically within 7 months of the index stroke in one recent prospective study including 353 patients participating in a randomized therapy trial [14]. Recurrent ischemic stroke in the same arterial distribution should influence the treating physician to consider intracranial atherosclerosis as a possible etiology that must be considered.

Case 4. More intracranial atherosclerosis

A 74-year-old woman with a history of previous stroke and previous TIA was referred to our stroke clinic regarding stroke etiology and further management. The patient suffered an ischemic stroke 13 months prior and a TIA 2 months prior to her office visit with us. Her stroke took place during a hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia. MRI diffusion demonstrated multiple acute diffusion restrictions, all small and all in the distribution of the right MCA territory. None were at the cortical surface; most approximated the MCA boundary zone (Figure 6.11). The patient recalled experiencing left-sided numbness and tingling and some left-sided weakness as well. She was very frightened by the event. However, she regained good motor function within 1 to 2 weeks and her sensory symptoms also subsided. Records from that hospitalization indicated no unusual findings on cardiac telemetry or ECG, an echocardiogram showed mild left ventricular hypertrophy only, and a carotid ultrasound study reportedly showed mild calcific plaque in the left carotid bulb but no atherosclerotic disease on the right. She was placed on aspirin 81 mg and clopidogrel at hospital discharge but left without a defined stroke etiology. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, mild renal impairment, and gastroesophageal reflux. She also had a history of recurrent headache with migrainous features and recurrent depression with occasional manic features. She had been a heavy cigarette smoker at one time but stopped smoking 20 years before her visit to our clinic. Alcohol use was minimal. Family history included both coronary artery disease and hypertension in both parents. She had a sister with migraine headache.

MR echo planar DWI demonstrating relatively linear cluster of small areas of restricted diffusion not extending to the cortical surface (arrow in a) and deeper not quite as linear areas of diffusion restriction approaching the lateral ventricle (b). This deeper MCA boundary zone pattern suggests artery to artery embolism associated with limited flow, more likely due to MCA than cervical ICA disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree