CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

HISTORY

A thorough history is the most important element in the evaluation of a patient with chronic or recurrent headache. Temporal profiling assessing frequency and duration of headaches should precede and help guide symptomatic assessment. Headaches lasting hours to days and recurring over years should prompt questions probing for migraine, while episodes lasting 1 hour and occurring nocturnally for only the prior 6 weeks should generate questions looking for cluster headaches. The essential elements in headache evaluation would include the following components and questions.

A. Age of onset. “How old were you when you had your first memorable headache?” A headache history dating back for years is certainly more comforting, and likely to reflect primary headache, than those histories dating back only a few weeks or months. Most primary headaches develop between the ages of 5 and 50, and onset outside this range should signal the possibility of a secondary headache disorder. In addition, the age–incidence curve for brain tumors displays a bimodal distribution, peaking at ages 5 and 60.

B. Temporal profile. “How long have your headaches been like this—this frequency, this intensity—we are discussing today?” An accurate assessment of headache frequency is crucial in headache management. Many primary headaches display stable patterns for months or years, while significant secondary headaches are defined by progression or instability of pattern—typically over a period of 6 months or less. Cluster headache patients experience cycles of daily headache for periods of several weeks to months, then often becoming dormant for months or years. Any fundamental change in headache pattern over a period of days to months should signal the possibility of a secondary headache disorder.

1. “How many days per month do you have headache of any kind, any degree?” This question is often overlooked but is exceedingly important. The number of total headache days in an average month is important both diagnostically and therapeutically. Those with primary headache disorders such as migraine and tension-type headaches will be designated as “chronic” when there are 15 or more days of headache in an average month. In addition, preventive treatments should be prescribed for migraine or tension-type headache when the patient is averaging at least 8 days of headache per month.

2. “How many of those headaches become severe? How long do these episodes last, without treatment or if treatment does not work?” Migraine headaches sometimes become severe, and when untreated in adults last 4 to 72 hours. Tension-type headache episodes are rarely if ever severe and last hours to days. Cluster headache attacks are almost always severe, with typical duration between 15 minutes and 3 hours. Other TACs are characterized by even shorter episodes—chronic paroxysmal hemicranias (CPHs) 2 to 30 minutes, short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) 1 to 600 seconds. Trigeminal neuralgia pains also typically last several seconds at most.

3. “How many days each month do you take a medication to treat a headache?” Screening for possible medication overuse, previously known as “rebound” headache, is helpful. Those patients using acute headache medications more than 10 or 15 days per month (based on the medication) may find themselves refractory to preventive measures until the overused agent is discontinued.

C. Pain characteristics.

1. “Where does it hurt?” Location of head discomfort in both primary and secondary headache disorders is incredibly variable and often unhelpful diagnostically. Migraine is unilateral in 60% of patients, often switching sides, but it may be bilateral or global in 40%. Tension-type headache is most commonly but not universally bilateral, with either frontotemporal or occipital predominance. Cluster headache and other TACs are typically unilateral and involve V1 distribution pain, trigeminal neuralgia unilateral and V2, V3 distribution pain, but both may occasionally occur bilaterally. Structural disease of the orbits and sinuses is typically worse frontally, while that of the cervical spine is worse occipitally. Intracranial vascular or mass lesions and disorders of intracranial pressure may present with pain anywhere in the cranium, with occasional radiation to the face or neck.

2. “Describe the quality of the pain? What does it feel like? Are the severe headaches steady or throbbing?” Questions to pain quality do not help distinguish secondary headache syndromes but may help in the diagnosis of primary headaches. Although steady in up to 30%, the pain of migraine is usually throbbing. Tension-type headache is generally described as pressure, aching, or tightness. Cluster headache is classically piercing or boring in nature, but may burn or throb in some. Stabbing pain is characteristic of primary stabbing headache and trigeminal neuralgia.

3. “On a scale of 1-10, how severe is the pain on bad days? On that same scale, how intense are the minor headaches?” The usefulness of a linear pain scale is limited, given the variability of pain perceptions and prior pain experiences across patient populations. These values are perhaps most useful in the longitudinal management of individual patients where improvements in headache intensity following treatment may be quantified.

4. “Is the pain worse with routine physical activity, such as bending over or going up a flight of stairs?” Disorders of intracranial pressure may worsen with changes in posture or activity. When severe migraine is typically worsened by physical activity, cluster headache is unaffected, and tension-type headache either unaffected or improved. An interesting follow-up question here is, “What do you do when you get a bad headache?” Migraine patients tend to resort to bed rest in a quiet and dark environment, tension-type with mild or no alterations in activity, while cluster patients are restless and often pace or participate in some distracting behavior.

D. Associated features.

1. “Do you have any symptoms preceding the pain that suggest a headache is likely to occur?” Migraine may be preceded by a prodrome characterized by vague constitutional or mood symptoms lasting hours, or aura involving discrete neurologic symptoms lasting minutes. Most patients with other primary headaches and those with secondary headaches have few if any premonitory signs.

2. “Are you sensitive to light or noise during headaches?” Significant sensory sensitivities are typical of migraine, common in cluster, and rare in tension-type headache. Photophobia may also be seen in patients with glaucoma or disorders affecting the meninges.

3. “Are you nauseated or do you vomit with some headaches?” Similar to the element of sensory sensitivities, nausea and vomiting are typical of migraine, common in cluster, and rare in tension-type headache. Over 70% of patients with migraine will experience nausea, and 30% vomiting. These symptoms are also common in those patients with secondary headache disorders involving increased intracranial pressure.

4. “Do you experience changes in your vision or speech, or do you have any weakness or numbness during headache attacks?” Neurologic symptoms lasting 5 to 60 minutes preceding a severe headache may constitute aura. Such complaints typically involve visual, hemisensory, or language functions of the brain (Video![]() 21.1). Brainstem symptoms such as vertigo, diplopia, or ataxia may reflect brainstem aura, and focal weakness hemiplegic migraine, but both of these subtypes of migraine are uncommon. Any patient presenting with headache and neurologic symptoms that are not typical of migraine aura should undergo neuroimaging.

21.1). Brainstem symptoms such as vertigo, diplopia, or ataxia may reflect brainstem aura, and focal weakness hemiplegic migraine, but both of these subtypes of migraine are uncommon. Any patient presenting with headache and neurologic symptoms that are not typical of migraine aura should undergo neuroimaging.

5. “Do you have tearing, eye redness or drooping, or nasal congestion or drainage associated with headache attacks?” Cranial autonomic features are seen in up to 50% of patients with migraine. These are often bilateral and frequently lead to a misdiagnosis of sinus headache. The presence of unilateral autonomic features is a hallmark of cluster headache and the other TACs. The absence of such features assists in the distinction between these headaches and trigeminal neuralgia.

E. Triggers or risk factors.

1. “Are there any triggers that seem to cause some of your headaches?” “Is there any association with stress, hormone or weather changes, exposures to bright or flashing lights, loud noises, or strong odors?” Migraine headache patients may describe a variety of internal or external stimuli affecting the likelihood of a subsequent headache attack. Stress, female hormone or weather changes, or exposure to excessive light, noise, or odors may all trigger migraines. Changes in sleep or meal patterns and certain foods or dietary elements such as artificial sweeteners or monosodium glutamate may also be provocative. Stress, neck or eye strain, or sleep deprivation may impact tension-type headache. When in the midst of a cycle, cluster headache patients may report alcohol as a trigger, while between cycles alcohol is not problematic. Some primary headaches are defined by the trigger: primary cough headache, primary exercise headache, and primary headache associated with sexual activity. Certain secondary headaches are also defined by exposure (carbon monoxide) or withdrawal (caffeine) from certain substances.

F. Family history.

1. “Is there any family history of migraine or other headaches?” Aside from those extended family histories of brain tumor or aneurysm, patients with secondary headache disorders typically do not possess a family history of relevance. Tension-type and cluster headaches seem to possess only minor genetic influences. A family history of headache is most important in migraine: approximately 50% of patients report a first-degree relative with migraine, and some reports indicate up to 90% will have some family history of headache.

1. Pulse and blood pressure should be checked. Uncontrolled hypertension may be associated with secondary headache, although the connection is possibly overstated. Bradycardia or tachycardia may indicate thyroid disease, which may cause headaches. Blood pressure and pulse values may also impact choices of medications used in the prevention or acute management of headache. -blockers may reduce, and tricyclic antidepressants increase, heart rate and blood pressure.

2. The cervical spine musculature should be palpated for spasm or trigger points, and the cervical range of motion assessed. Abnormal cervical spine exam findings could suggest a secondary cervicogenic headache disorder. Tenderness at the occiput could suggest occipital neuralgia.

3. Assessment of the ears, sinuses, mastoids, and cervical glandular tissues may reveal evidence of malignant, infectious, or granulomatous conditions. Thyromegaly may indicate thyroid dysfunction.

4. Temporal artery palpation for pulsation and tenderness should be performed in older adults to screen for giant cell arteritis (GCA). Temporomandibular joint dysfunction as a cause for headache may be suggested by crepitus, diminished range of motion, or tenderness on joint assessment.

5. A thorough examination of the eyes is critical in the evaluation of patients with headache. Ptosis or miosis may be seen with primary headaches such as cluster but also may reflect secondary pathologies such as carotid dissection or stroke. Glaucoma may present with conjunctival injection and pupillary abnormalities. Papilledema on fundoscopic examination arising from increased intracranial pressure may be seen with intracranial mass lesions, venous or sinus thrombosis, obstructive hydrocephalus, or idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). Visual acuity may be affected by glaucoma, optic nerve tumors, or optic neuritis. Visual field defects are typically associated with certain structural lesions along the visual pathways, with bitemporal hemianopsia seen with pituitary tumors and homonymous hemianopsia seen with occipital stroke or mass.

6. Cranial nerve examination helps further identify those patients experiencing headaches from structural lesions. Ophthalmoplegia may occur with intracranial lesions or with structural pathologies in the orbit or cavernous sinus. Chronic sphenoid sinusitis extending to the cavernous sinus or orbital tumor or pseudotumor are some examples. Unilateral or bilateral sixth-nerve palsies may act as a “falsely localizing sign” since either may occur with increased intracranial pressure. Facial palsies and hearing impairment may be associated with lesions in the posterior fossa such as acoustic neuroma, or with intracranial extension of chronic mastoiditis.

7. Focal deficits on sensory or motor testing would typically indicate structural lesions of the central nervous system. Occasionally cervical root compression could result in ipsilateral radicular numbness, focal weakness, or hyporeflexia. Hyperreflexia, Babinski’s signs, or ataxia also would be indicative of lesions in the brain or cervical spinal cord.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

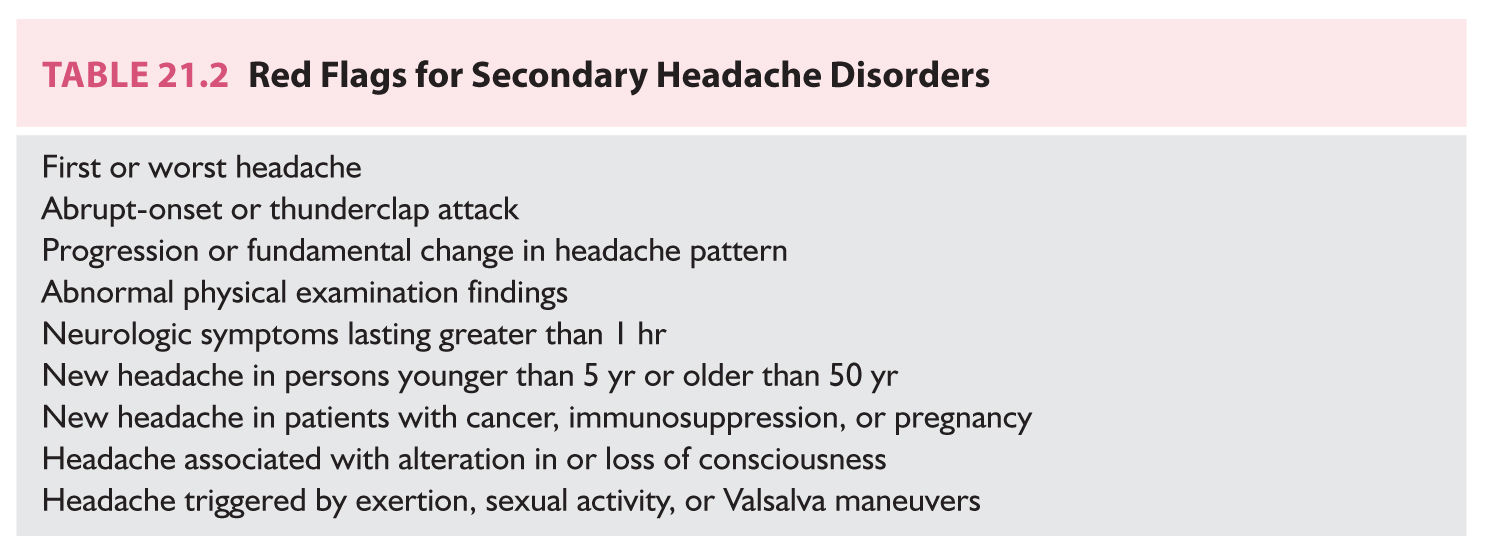

1. The majority of patients presenting with chronic or recurrent headache will not require diagnostic evaluation. Most will display a history compatible with a primary headache and a normal neurologic examination. Guidelines recommend against neuroimaging in the setting of a stable pattern of migraine headache. Less than 1% of such patients will have neuroimaging abnormalities, the majority being benign. There are no evidence-based guidelines available for imaging in chronic nonmigrainous headaches. The presence of one of the red flags for secondary headache should prompt neuroimaging as well as other specific diagnostic studies (Table 21.2).

2. In certain settings blood work may be required to exclude secondary headache disorders. Measurement of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein is necessary in the evaluation of potential GCA, and subsequent temporal artery biopsy may be indicated to confirm the diagnosis. Serum toxicology, carboxyhemoglobin, and thyroid function tests may also help identify specific secondary headaches.

3. Neuroimaging is the most important diagnostic tool in the assessment of patients with headache. Head computed tomography (CT) is the preferred imaging modality in the setting of acute headache. Skull fracture, acute intracranial hemorrhage, and paranasal sinus disease may be identified. Guidelines now recommend MRI of the brain in the evaluation of patients with chronic or recurrent headache. Although more expensive than head CT, MRI is considered more sensitive in identifying intracranial pathology. Given the absence of radiation exposure MRI is also considered less invasive. Contrast administration may be indicated in settings of malignant, infectious, or inflammatory disease. In addition, most patients with headache from intracranial hypotension will display diffuse non-nodular diffuse meningeal enhancement. CT or MR angiographic or venographic studies may be useful in the settings of suspected vascular occlusion or malformation.

4. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination is mandatory in the setting of CT-negative subarachnoid hemorrhage. Certain patients with chronic headache disorders may also benefit from lumbar puncture. Measurement of the opening pressure may confirm the presence of either intracranial hypertension or hypotension. Those with subacute meningoencephalitis may show abnormalities in CSF cell count, protein, or glucose. Cultures, gram stains, antibody panels, and polymerase chain reaction analysis may isolate specific organisms. CSF cytology is indicated with suspected leukemic, lymphomatous, or carcinomatous meningitis.

5. There is no role for electroencephalography in the workup of patients with headache unless there is impairment of consciousness or seizure-like activity associated with attacks.

SECONDARY CHRONIC OR RECURRENT HEADACHE DISORDERS

Posttraumatic Headache

Trauma to the head or neck may result in headaches, which may be acute or recur chronically. ICHD classification arbitrarily defines acute posttraumatic headache as recurring up to 3 months following an injury, while the term persistent posttraumatic headache is applied to those with headaches extending beyond that time.

1. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) may occur when the nervous system is exposed to either blunt or penetrating trauma. Most patients with obvious structural lesions, such as epidural or parenchymal hemorrhages, will present with acute headaches. Some patients, particularly the elderly or those on anticoagulants, may develop subdural hematomas that present with more subacute or chronic patterns of headache. This may even occur in the setting of relatively insignificant trauma.

2. Headache is a common result of mild TBI, or concussion. This symptom is the most common reported by those with a postconcussion syndrome. Cognitive impairment, fatigue, sleep disturbances, dizziness, and visual blurring are other typical complaints. Posttraumatic headaches typically resolve within a matter of days to weeks, but some experience headaches lingering for months to years. There is no direct correlation between the degree of trauma and either the duration or severity of the subsequent headache condition. Management of the assorted symptoms of the postconcussion syndrome is largely rehabilitative and symptomatic. It may be helpful to phenotype the headache complaints as either more tension-type or migraine in quality, directing pharmacotherapy accordingly.

3. Cervicogenic headache arises from irritation of upper cervical nerve roots caused by bone, disc, or soft tissue pathology. This is usually but not invariably accompanied by neck pain. Although sometimes atraumatic in origin, cervical sprain or “whiplash” injury is the most common cause of cervicogenic headache. Pain is frequently side-locked, worsened by neck motion, and associated with cervical abnormalities on examination or imaging. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and muscle relaxants are often helpful acutely. Physical therapy or manipulation, preventive medications such as amitriptyline or gabapentin, and procedures such as occipital nerve or cervical facet blocks may be helpful in chronic cases.

4. Dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint may occur following facial trauma, possibly arising from airbag deployment during a motor vehicle accident. The pain may be unilateral or bilateral and is typically temporal and aggravated by chewing. The appearance is similar to tension-type headache and the pain often responds to local ice, NSAIDs, and a soft diet. Referral to a dentist or maxillofacial specialist may be required in chronic cases.

5. Occipital neuralgia may present as episodes of severe, shooting pain in the distribution of the greater, lesser, or third occipital nerves. A lingering dull discomfort may persist between paroxysms of severe pain lasting seconds to minutes. The neuralgia may arise from trauma to one of the upper cervical roots or to the nerves themselves in the posterior scalp and may be unilateral or bilateral. Local tenderness or a Tinel’s sign may be present. Analgesics are typically unhelpful, while many patients respond to daily amitriptyline or gabapentin. Occipital nerve blocks or cervical facet blocks may be beneficial as well.

HEADACHES SECONDARY TO CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE

Most patients with headaches of cerebrovascular origin will present acutely. Subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, or dissection of the cervical-cephalic vessels will present with acute headache that is frequently abrupt and “thunderclap” in description. Following the acute presentation some may develop ongoing headaches that may resemble migraine or tension-type headache extending for months or years. These are often refractory to medical management but fade with time.

1. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins or sinuses may result in acute or more chronic headaches. Headache is the most common symptom, seen in 80% to 90%, and is the most common presenting symptom. Other symptoms are highly variable, but the majority of cases are associated with papilledema or focal neurologic findings. Suspicion should be raised in the presence of prothrombotic conditions such as malignancy, pregnancy, or the use of oral contraceptives. Management steps include symptomatic care and heparin followed by oral anticoagulation for 3 to 6 months.

2. Unruptured cerebral aneurysms are present in 0.4% to 3.6% of the population. Headache has been reported in up to 20% of these individuals, but usually the aneurysm is an incidental finding. The typical presentation of headache from cerebral aneurysm is an isolated thunderclap attack, but up to 40% will experience a precursor “sentinel leak” headache a few days or weeks prior to aneurismal rupture.

3. Vascular malformations of the brain or dura may be linked with recurrent headaches. Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) may present with headaches in approximately 15% of cases. Atypical presentations of migraine, cluster, and CPHs have been reported. Many may be incidental, with the strongest case for pathophysiologic link made for those with headache locked ipsilateral and neurologic symptoms contralateral to the AVM. Cavernous angiomas also may be associated with headache in up to 40% of cases, with chronic patterns suggestive of migraine and abrupt headache with acute hemorrhage.

4. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) is characterized by recurrent thunderclap headache associated with multifocal segmental cerebral vasoconstriction. Patients may also present with focal neurologic findings, encephalopathy, and seizures. Brain MRI may be normal or show findings consistent with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. CSF is typically normal. RCVS can occur spontaneously or in association with preeclampsia or eclampsia, medications (sympathomimetic agents), blood product transfusions, or pheochromocytoma. Calcium-channel blocker administration (nimodipine or verapamil) is recommended. Intravenous magnesium is added in cases of preeclampsia or eclampsia. The role of corticosteroids is unclear.

5. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system is often confused with RCVS. Headaches, however, are more insidious and progressive. Brain MRI shows subcortical white matter and cortical infarctions in the majority. Over 95% of patients show CSF abnormalities including elevations in cell counts, protein, and opening pressure. Combined immunosuppressive therapy with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide is recommended.

6. Headache is the most common presenting symptom of GCA. This condition involves inflammation of the large arteries with a preference for head and neck vessels. Incidence peaks between 70 and 80 years of age, and GCA is more common in Whites and women. Headache is classically temporal but location is highly variable. Other common complaints include myalgias, fatigue, malaise, fevers, anorexia, and weight loss. Jaw claudication is present in only 25% of cases. Cranial nerve palsies and stroke may sometimes occur. ESR is elevated in 95% of biopsy-proven GCA cases, with a mean value of 85 mm/hour. Diagnosis may require bilateral temporal artery biopsies of at least 2 cm in length. Treatment with 1 mg/kg prednisone should be instituted at the first sign of suspicion for GCA, since vision loss is permanent once identified. Prednisone may be necessary for 6 to 24 months, with most patients tapered to 10 mg daily over the first few months. Both clinical and laboratory values are helpful in assessing improvement or relapse.

7. Certain genetic vasculopathies may present with recurrent headache, often exhibiting migrainous features. Cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy presents with migraine with aura in one-third of cases. It affects small arteries and also results in mood disorder, stroke, and dementia. Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes may frequently present with migrainous headaches and stroke-like events, in addition to seizures, recurrent vomiting, and sensorineural deafness. Treatment of both is generally symptomatic.

HEADACHE FROM NONVASCULAR INTRACRANIAL DISORDERS

1. Headache associated with brain tumor is highly variable. Approximately 20% of patients will present and 60% eventually develop headache linked to the malignancy. It is more common with infratentorial tumors. Symptoms may arise from the mass lesion, from obstructive hydrocephalus, or from meningeal irritation from carcinomatous meningitis. The classic presentation of headache worse in the morning with associated vomiting is present in approximately 10% of cases. Most will exhibit headaches phenotypically similar to tension-type headache, or occasionally similar to migraine.

2. IIH involves CSF pressure elevation in the absence of an intracranial space-occupying lesion. Approximately 90% of subjects are female, 90% of childbearing age, and 90% with elevations in body mass index. Headache, often tension-type in nature, and visual complaints are most common at presentation. Blurring or episodic darkening of vision, diplopia, pulsatile tinnitus, and neck pain are frequently noted. Papilledema is present nearly universally, and sixth-nerve palsy on occasion. Elevated CSF opening pressure (>250 mm H2O in adults) in the absence of intracranial lesions confirms the diagnosis. Up to 90% will display blind spot enlargement or peripheral field loss on visual perimetry. Treatment is aimed at preservation of vision and minimization of headaches. Acetazolamide is the drug of choice, although many now prescribe topiramate for the added benefit of weight loss. Weight reduction through diet and exercise or through bariatric surgery has also been shown to be beneficial. Optic nerve fenestration or shunt procedures may be required in refractory cases.

3. Headache from intracranial hypotension is most frequently seen in the setting of recent lumbar puncture, but may occur spontaneously (SIH) as well. The triad of orthostatic headache, diffuse pachymeningeal enhancement on brain MRI, and low CSF pressure (<6 cm water) is characteristic. The headache may be generalized or focal and develops within 15 minutes after leaving a supine position. Cervical discomfort, stiffness, nausea, vertigo, and hearing changes such as muffling or tinnitus are other common complaints. Diplopia may be seen in the presence of sixth-nerve palsy but most patients present with normal neurologic examinations. Predisposing conditions for SIH include trauma, Marfan or Ehler–Danlos syndromes, and neurofibromatosis. Roles for disc disease or dural diverticula are unclear. In addition to non-nodular diffuse pachymeningeal “thickening” with contrast enhancement, brain MRI may reveal subdural fluid collections, pituitary enlargement, or tonsillar herniation. Identification of the site of CSF leak in cases of SIH can be challenging. CT myelography of the entire spine is the recommended study. Initial management involves bed rest and fluid resuscitation. When required, epidural blood patch is associated with resolution of symptoms in 90% to 95% of cases. Lumbar patches may be helpful both in the settings of postdural puncture headache and SIH, but some with the latter may require cervical or thoracic patches or surgical procedures. The rate of recurrence is approximately 10%.

4. Involvement of the nervous system from noninfectious inflammatory disease may also produce headache. Neurosarcoidosis may present with meningeal involvement or with focal inflammatory lesions in the brain parenchyma or periventricular white matter. Aseptic meningitis may recur in patients with certain autoimmune disorders or with exposure to certain drugs such as NSAIDs, penicillins, or immunoglobulin. Resolution with treatment of the cause is typical. The syndrome of transient headache and neurological deficits with cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis is characterized by migraine-like headaches with unilateral sensorimotor or speech deficits of duration greater than 4 hours. CSF analysis reveals >15 lymphocytes. The condition resolves spontaneously within 3 months.

5. Chiari I malformations may be associated with chronic or recurrent headaches. Population prevalence is nearly 1%. Women are more likely to be affected than men, and there may be a slight hereditary component. Chiari I is identified by cerebellar tonsillar descent of >5 mm (below the line connecting the internal occipital protuberance to the basion), or descent of >3 mm with crowding of the subarachnoid space at the craniocervical junction. By definition headache has at least one of the following three characteristics: triggered by cough or other Valsalva-like maneuver; occipital or suboccipital location; duration <5 minutes. Dizziness, ataxia, changes in hearing, and diplopia or transient visual phenomena are not unusual. Neurologic examinations are typically normal but may show brainstem or cerebellar findings. Cervical spine abnormalities may be seen when the Chiari is complicated by a cervical cord syrinx. Significant symptomatic overlap may be seen with migraine. Surgery should be reserved for those patients exhibiting abnormalities on physical exam, or for those with refractory headaches exhibiting features characteristic of a Chiari. The role of Cine MRI CSF flow study is unclear.

HEADACHES ATTRIBUTED TO SUBSTANCES

1. Recurrent headache may be associated with the use of multiple substances or their withdrawal. Although the list of agents potentially causing headache is lengthy, classic perpetrators include nitrates, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, alcohol, and endogenous hormones. Caffeine withdrawal is one of the most common causes of substance-related headaches.

2. Headaches associated with overtreatment with acute medication is now termed “medication overuse” headache (MOH). It is defined as headache occurring on 15 or more days per month developing as a consequence of regular overuse of acute or symptomatic headache medication (on 10 or more, or 15 or more days per month, depending on the medication) for more than 3 months. MOH requires both the presence of an offending agent and susceptible individual. The presence of a primary headache disorder seems crucial, and those with migraine and tension-type headache seem most susceptible. MOH is present in up to 80% of individuals with chronic migraine. Simple analgesics are linked with the 15-day threshold, while the use of triptans, ergots, opioids, or combination analgesics at least 10 days per month is considered excessive. Several studies have associated opioids (critical exposure 8 days per month) and barbiturates (critical exposure 5 days per month) with higher rates of transformation to chronic migraine when compared to NSAIDs or triptans.

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA

The most commonly diagnosed recurrent facial pain is trigeminal neuralgia. ICHD criteria define those cases arising from structural lesions or trauma as “painful” trigeminal neuralgia, while those without these etiologies are considered “classical.” It is characterized by paroxysms of brief electrical shooting pain limited to the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Approximately 95% of cases involve pain isolated to the second and third branches of the nerve, and 95% are strictly unilateral. By definition the pain lasts only a fraction of a second to 2 minutes and may be triggered by innocuous stimulation of the face. Pains can occur in series, which may be followed by refractory periods of quiescence. Some experience cycles of recurrent pain lasting weeks to months, interrupted by periods of remission, while other patients follow a chronic progressive course. Onset occurs after age 40 in 90%. Those diagnosed at a young age should be evaluated for structural lesions such as multiple sclerosis. Vascular compression of the trigeminal root entry zone in the pons is responsible for most cases of “classical” trigeminal neuralgia. Carbamazepine is the drug of choice. In certain cases oxcarbazepine, baclofen, gabapentin, clonazepam, or lamotrigine may be helpful. Medical therapy fails in approximately 30% of cases. In those who are good surgical candidates, microvascular decompression is the procedure with highest rate of success.

PRIMARY HEADACHE DISORDERS

Migraine Headache

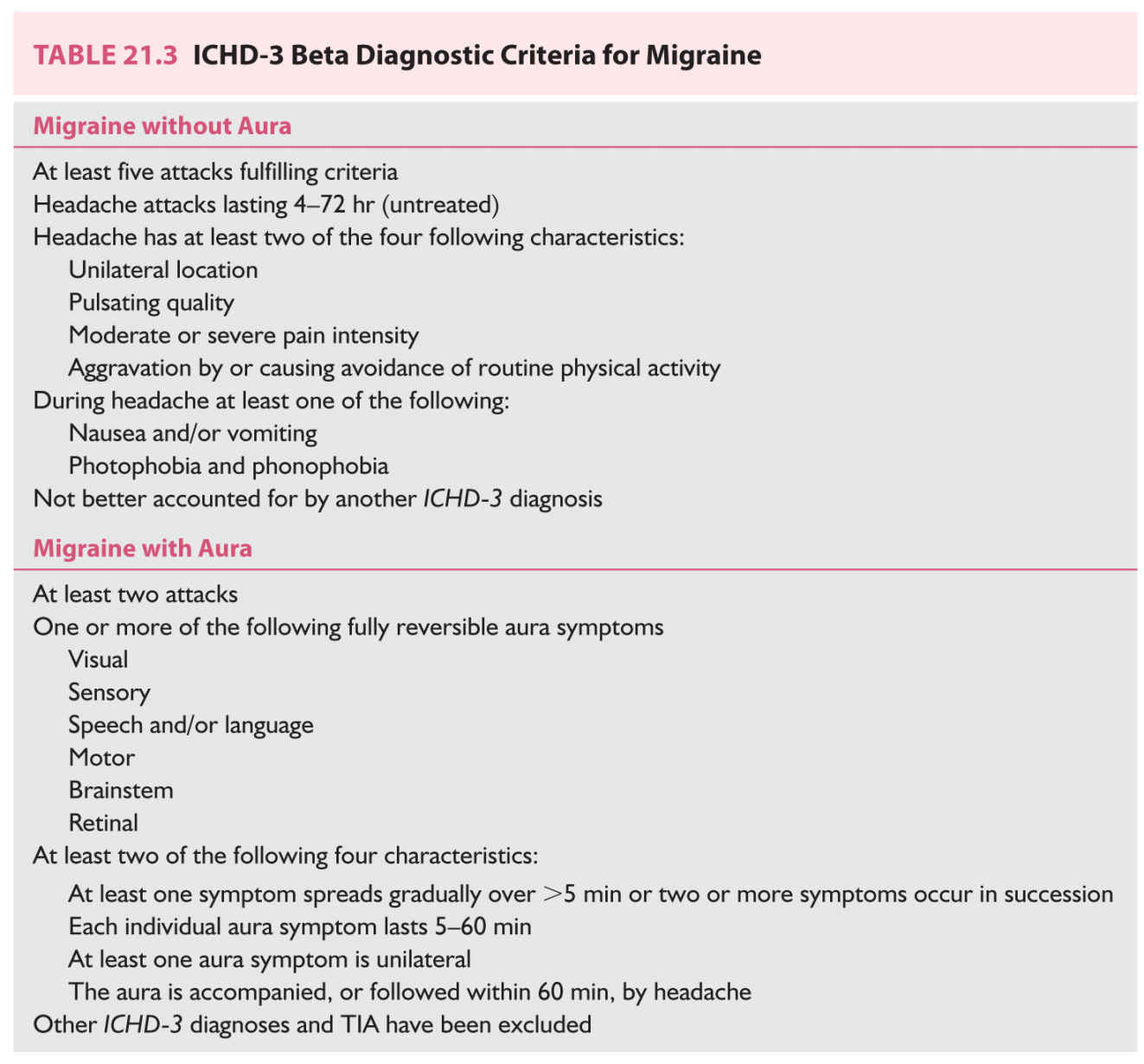

1. The vast majority of patients seen for recurrent or chronic headaches will suffer from migraine. The combination of high population prevalence (13% of US adults) and significant morbidity of the condition leads to the figure that over 90% of patients presenting with recurrent headache in a primary care setting meet criteria for migraine. Incidence peaks in late childhood and early adolescence, and prevalence in the fifth decade of life. It is three times more common in adult women than men. Migraine is characterized by recurrent episodes of severe headache lasting hours to days with associated nausea or sensitivities to light or noise. Although vomiting and aura are held by many as cardinal features of migraine, these symptoms are actually seen in only 25% to 30% of patients. Formal diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 21.3.

2. Because of tremendous phenotypic variations seen in the population, migraine is frequently misdiagnosed. Although absent from diagnostic criteria, neck pain is seen in 75% and nasal congestion or tearing in 50%. The former may lead to a label of “tension” headache, the latter to “sinus” headache. Most patients with migraine will experience both minor and severe attacks, further clouding the picture diagnostically for patients and clinicians.

3. Aura is seen in up to 30% of those with migraine. Aura may come before, during, or completely separate from headache. Any combination of visual, sensory, or language dysfunction without retinal, brainstem, or motor complaints is termed typical aura. Those with aura isolated to one eye are termed “retinal aura.” These patients should be screened for retinal issues such as ischemic optic neuropathy or detachment. Migraine with brainstem aura, previously called basilar-type migraine, must possess at least two of the following: vertigo, diplopia, ataxia, tinnitus, hyperacusis, dysarthria, and decreased level of consciousness. Those with any degree of motor weakness are termed hemiplegic migraine, which has both familial and sporadic subtypes. Triptans are contraindicated in those with brainstem or hemiplegic aura.

4. Migraine is subclassified as “episodic” when occurring fewer than 15 days per month. It is termed “chronic” when occurring at least 15 days per month for 3 months and exhibiting migraine features or response to migraine medication on at least 8 days per month. Transformation of episodic into chronic migraine has been shown to occur at a rate of 3% per year in the general population. Risk factors for development of chronic migraine include older age, female sex, major life changes or stressors, obesity, low socioeconomic status, head trauma, excessive caffeine or nicotine exposure, and the presence of pain, sleep, or mental health disorders. Acute treatment may play a role as well. Medication overuse, any exposure to opioid- or butalbital-containing products, and those experiencing inadequate results from acute therapies all have higher risk for chronic migraine.

5. It is often helpful to screen migraineurs for possible comorbidities. Mood disorders such as depression and bipolar disease, generalized anxiety and panic disorders, insomnia, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia are all commonly seen. Migraine with aura, particularly in women, also raises the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

Tension-type Headache

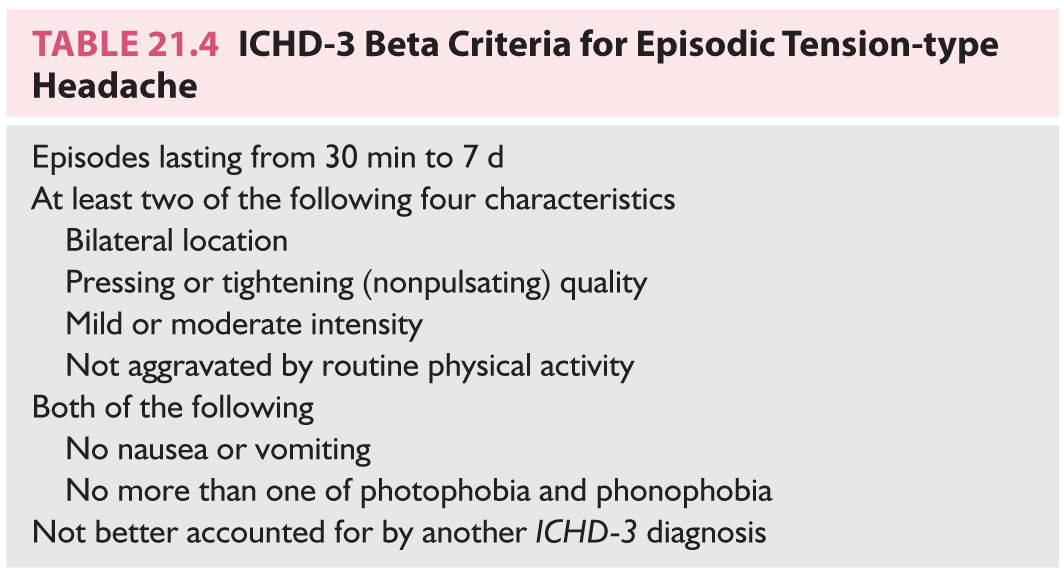

1. Tension-type headache is the most common and least distinct of the primary headache disorders. Annual prevalence in US adults approximates 40%, while lifetime prevalence approaches 90%. It is characterized by episodes of nondisabling headache that lack the severity, gastrointestinal issues, and sensory complaints seen with migraine. ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria are outlined in Table 21.4.

2. Tension-type headache is subclassified on the basis of frequency, which appears to be therapeutically helpful, and on the presence or absence of pericranial muscle tenderness, which is not particularly relevant. Episodic tension-type headache is “infrequent” when <1 day per month and “frequent” when 1 to 14 days per month. Chronic tension-type headache occurs on average at least 15 days per month. Those with chronic tension-type headache sometimes develop a picture somewhat similar to migraine and the diagnostic criteria permit one of the following: photophobia, phonophobia, mild nausea.

3. Given significant symptomatic overlap with secondary headaches and migraine, patients with chronic tension-type headaches should have those conditions excluded before the diagnosis is made.

4. Another headache phenotypically similar to chronic tension-type headache is a separate primary headache syndrome known as new daily persistent headache (NDPH). This condition is defined by a daily headache syndrome lasting for at least 3 months with a distinct and clearly remembered onset. NDPH pain begins abruptly, without provocation, and becomes continuous and unremitting within 24 hours. This condition is often seen in younger patients, frequently lasts for years, and has no known effective therapeutic option.

TRIGEMINAL AUTONOMIC CEPHALALGIAS

1. The TACs are a group of headache disorders characterized by episodes of severe pain in the distribution of the first division of the trigeminal nerve accompanied by ipsilateral autonomic features. They are subclassified based on the duration and frequency of attacks.

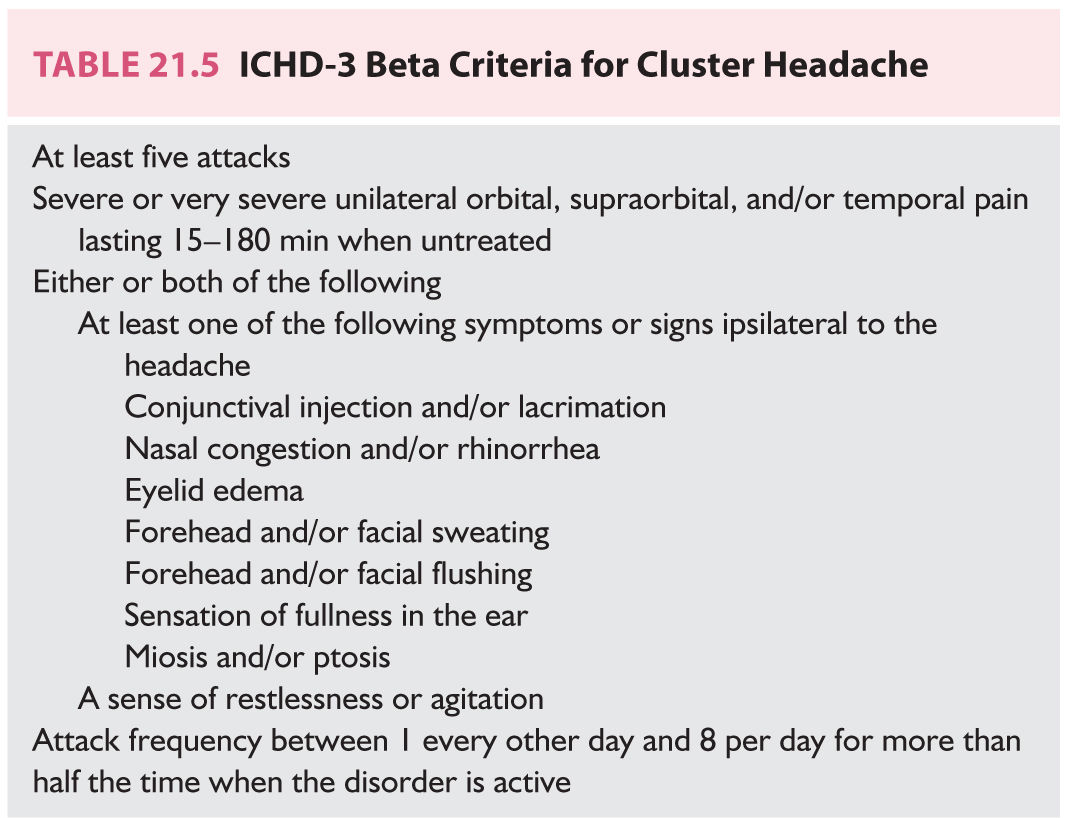

2. Cluster headache is the most prevalent TAC in the population. It is most commonly seen in men. Headache clusters generally last several weeks or months, separated by periods of remission. Circadian rhythmicity of attacks and circannual rhythmicity of cycles is frequently noted. Attacks of pain recur 1 to 8 times per day with duration 15 to 180 minutes. Pain is typically periorbital or temporal, intense, searing, with ipsilateral autonomic features such as ptosis, lacrimation, conjunctival injection, and nasal congestion and rhinorrhea (Table 21.5). Patients are often agitated and restless during acute cluster. Attacks may be triggered by alcohol and often occur nocturnally. Workup should include brain MRI to exclude secondary pathology. The most effective acute treatments are 100% oxygen delivered by face mask and subcutaneous sumatriptan. Steroids can be used to prevent cluster headache transiently, while verapamil is considered the drug of choice for prevention of cycles of greater than 2 weeks in duration.

3. CPH is a rare TAC marked by relatively short attacks of very severe lateralized pain with cranial autonomic features and definable response to indomethacin. Attacks usually occur 8 to 20 times daily and last 2 to 30 minutes.

Though the majority of attacks are spontaneous, 10% of attacks may be precipitated mechanically by bending or rotating the head or via external pressure against the transverse processes of C4–C5 or the greater occipital nerve.

4. Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing or cranial autonomic symptoms (SUNCT/SUNA) is an extremely rare condition marked by very short-lasting attacks (1 to 600 seconds) of lateralized severe head pain with prominent cranial autonomic features lingering beyond the period of pain. Attacks may involve isolated brief stabs of pain or series of stabs, and minor discomfort with or without interval. Patients may describe dozens or hundreds of attacks per day. Episodes may be triggered by trigeminal or extratrigeminal stimulation without refractory periods. SUNCT and SUNA are typically refractory to medical management, although case reports suggest possible response to lamotrigine.

5. Hemicrania continua (HC) is characterized by a continuous, side-locked, unilateral headache of variable intensity. Exacerbations of sharp pains lasting seconds to hours are common, some with occasional migrainous features. A foreign body sensation affecting the ipsilateral eye is relatively common. Like CPH the diagnosis of HC requires response to indomethacin.

Key Points

• The vast majority of patients presenting with chronic or recurrent headache will meet criteria for migraine.

• Tension-type headache is the most prevalent but least distinct of the primary headache conditions.

• Brain MRI is the imaging modality of choice in the workup of chronic or recurrent headache, but is unnecessary in the setting of typical migraine.

• TACs are subclassified on the basis of the duration and frequency of attacks.

• Migraine aura is classified as “typical” when involving only visual, hemisensory, or language impairment. The presence of any motor weakness leads to the diagnosis of “hemiplegic” aura, and the presence of brainstem symptoms such as vertigo, diplopia, and ataxia to the diagnosis of “brainstem” aura.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree