6. Dysphagia is rarely present in isolation when due to an underlying neurologic disease. Thus, changes in vision, speech, strength, coordination, and sensation should be explored. Speech changes are particularly useful to discriminate among neurologic causes of dysphagia: a spastic dysarthria can indicate motor neuron disease, hypophonia can signal parkinsonism, a nasal speech can be seen with bulbar weakness from neuromuscular disease, nasal regurgitation of fluids points to a problem with the innervation of the soft palate, and stridor may denote a problem involving the recurrent laryngeal nerve or the brainstem (such as in multiple system atrophy).

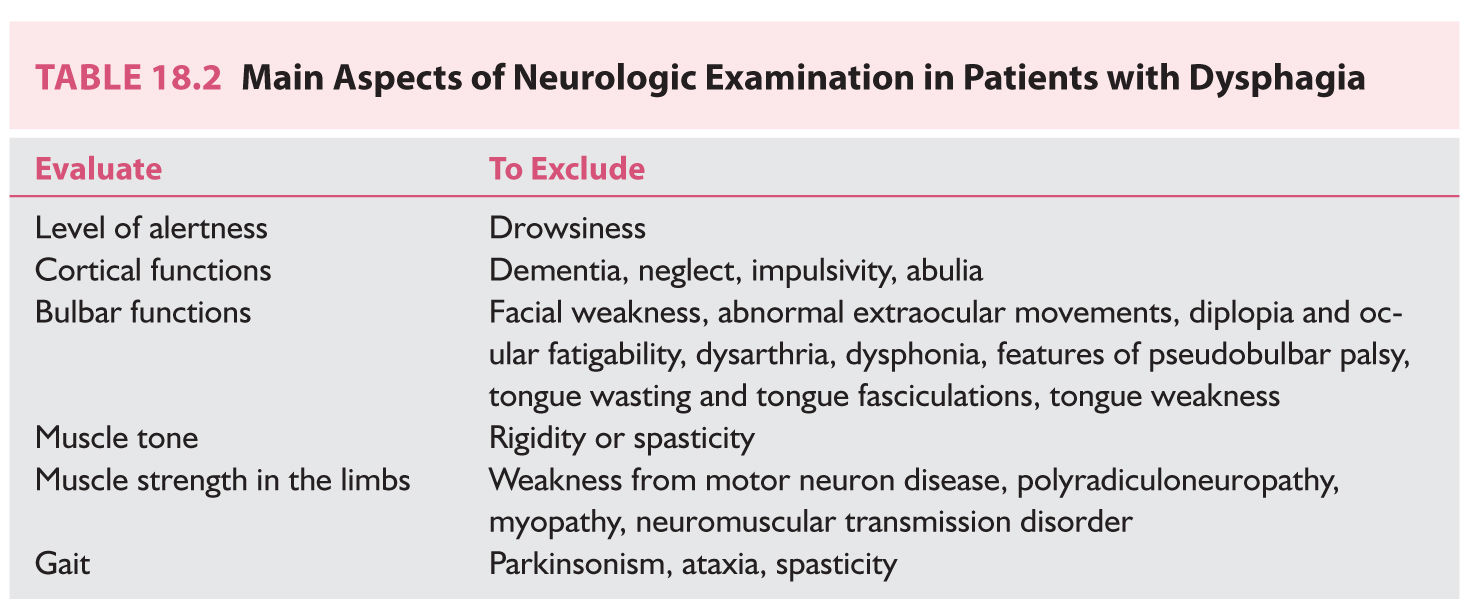

7. A complete neurologic examination should follow the careful history taking. The most relevant information that should be acquired from the neurologic examination in patients with dysphagia is shown in Table 18.2. The physical examination should also include evaluation of the lungs to exclude signs of aspiration. Specific evaluation for the presence of dysphagia per se is discussed below.

8. Recurrent episodes of pneumonia should always raise the suspicion of aspiration and call for detailed evaluation for possible dysphagia. Remember that dysphagia can be silent in patients with neurologic disease affecting the sensory innervation to the larynx.

COMPLICATIONS

1. Aspiration pneumonia. The risk of aspiration pneumonia is greatest in patients with acute neurologic disease, particularly stroke, because these patients have not yet developed any compensatory mechanisms.

2. Malnutrition.

3. Dehydration.

5. Increased health care costs (gastric feeding, nursing care, hospitalizations for recurrent pneumonia).

COMMON NEUROLOGIC CAUSES OF DYSPHAGIA

A. Acute neurologic disease.

1. Stroke.

a. Brainstem strokes (pontomedullary infarctions in particular) cause the most severe and persistent forms of dysphagia.

b. Hemispheric strokes can cause dysphagia by interrupting the cortical or subcortical input to the medullary swallowing center. Dysphagia is more common with large strokes affecting the middle cerebral artery territory, but can also occur with smaller infarctions in cortical and subcortical locations.

c. Specific hemispheric lesion locations associated with dysphagia include pre- and post-central gyri, operculum, supramarginal gyrus, and respective subcortical white matter tracts. Post-central lesions appear to be associated with more severe dysphagia.

d. Dysphagia can be a manifestation of advanced subcortical ischemia (particularly with multiple small subcortical infarction).

e. It is frequently associated with aphasia, dysarthria, and speech apraxia.

f. Poststroke dysphagia is more common in older patients and especially in the elderly.

g. Swallowing problems after stroke can include poor coordination of motor function during the oral phases, impaired initiation of the pharyngeal phase, reduced pharyngeal peristalsis with increased pharyngeal transit times, and aspiration.

2. Traumatic injury.

a. Head trauma can cause dysphagia by disturbing the neurologic control of the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing.

b. Injuries to the head and neck can compound the problem.

c. Cervical spinal cord injury, especially if treated with an extensive spinal fusion, can also cause dysphagia.

3. Acute neuromuscular disorders.

a. Severe dysphagia can be seen in patients with Guillain–Barré syndrome. It is more common in patients with generalized weakness, neuromuscular respiratory failure, and dysautonomia. However, it can sometimes be noted in patients with more restricted forms of the disease, such as the Miller Fisher’s syndrome.

b. Acute dysphagia can be a manifestation of botulism and severe forms of inflammatory myositis.

c. Rarely, dysphagia can be a complication of botulinum toxin injections for treatment of cervical dystonia or spasmodic dysphonia.

B. Chronic neurologic disease.

1. Parkinson’s disease (PD) and other extrapyramidal disorders.

a. Dysphagia is commonly considered a feature of advanced PD, but mild swallowing impairment can be detected in early stages.

b. Swallowing problems include defective mastication, impaired coordination of the tongue movements (patients with advanced PD often have an involuntary rocking, rolling tongue motion that interferes with the preparation of the bolus), and delayed transfer of the bolus to the pharynx. In turn, the pharyngeal phase is also delayed and the stasis of the bolus in the pharynx increases the risk of aspiration. Furthermore, patients with PD can aspirate silently (i.e., without cough).

c. Dysphagia and increased risk of aspiration can also be seen with other extrapyramidal disorders, most notably with progressive supranuclear palsy in which swallowing problems can be severe from an early stage of the disease.

2. Degenerative dementia.

a. Although dysphagia is not often appreciated as a common manifestation of degenerative dementias, epidemiologic studies have reported a fairly high incidence of this complication.

b. In patients with Alzheimer’s disease, studies have reported complaints of dysphagia in 7% and objective evidence of dysphagia in 13% to 29%. Even higher rates of dysphagia have been reported in patients with frontotemporal dementia (19% to 26% subjective and up to 57% objective).

c. The rates of detection of dysphagia increase proportionally to the severity of the dementia and the age of the patient.

d. Poor insight can increase the risk of aspiration in patients with dementia and dysphagia, thus demanding close supervision.

3. Multiple sclerosis (MS).

a. Dysphagia can be an early or more commonly a late manifestation of MS. In late stages, it can be seen in up to two-thirds of patients.

b. Severity of the dysphagia depends on the localization and extension of the demyelinating lesions. It is more severe with brainstem demyelination.

c. Swallowing abnormalities can be multiple, including impaired lingual control and tongue base retraction, delayed pharyngeal trigger, diminished pharyngeal peristalsis, reduced laryngeal closure, and upper esophageal sphincted dysfunction. Sensory impairment in the pharyngeal and laryngeal mucosa can allow silent aspiration. Protective reflexes (laryngeal adduction and cough) may also be affected.

d. Aspiration pneumonia is one of the leading causes of death in advanced MS.

4. Motor neuron disease.

a. Dysphagia is a major complication of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and eventually occurs in all cases.

b. In early stages, the tongue is disproportionally affected and consequently the oral phases of swallowing are predominantly impaired.

c. As bulbar involvement progresses, the dysphagia becomes more severe as the dysfunction extends to other aspects of the swallowing mechanism. The pharyngeal triggering reflex gets delayed and weakened. Meanwhile, laryngeal muscles can become hypertonic and thus lose coordination with pharyngeal movements.

d. Aspiration risk becomes very high over the course of the disease and this should be anticipated.

5. Chronic neuromuscular disorders.

a. MG can cause dysphagia because of fatigability of the bulbar muscles. Thus, myasthenic patients should always be interrogated about symptoms of dysphagia (including whether they get tired of chewing toward the end of meals), particularly if the voice is nasal or hoarse.

b. Dysphagia is a very common manifestation of MG exacerbation and, in turn, aspiration pneumonia can precipitate a myasthenic crisis.

c. Rarely, dysphagia can be a presenting symptom of MG.

d. In myasthenic patients, dysphagia can be related to fatigability and weakness of the masticatory muscles, tongue, pharyngeal constrictor muscles, and the muscles responsible for laryngeal elevation.

e. Inflammatory body myositis can cause dysphagia early or later in the course of the disease.

f. Slowly progressive dysphagia is a frequent symptom in patients with oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy and myotonic dystrophy.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

After a detailed history and physical examination, patients at risk for dysphagia should have specific testing of their swallowing.

A. Bedside swallowing examination.

1. A bedside screening evaluation of swallowing is necessary in any neurologic patient who can be at risk of aspiration and it should be performed as soon as the condition of the patient allows it and before any oral intake.

2. In fact, documentation of performance of a bedside swallowing evaluation before any oral intake is mandatory for patients with acute stroke.

3. The water swallowing test (simply asking the patient to take a few sips of water and watching for signs of choking, coughing, or inability to drink) is quite sensitive for the detection of dysphagia when compared to instrumental gold standards (video fluoroscopic or fiberoptic endoscopic swallowing evaluations). Therefore, although its specificity may be suboptimal, it is a good and practical measure to screen for dysphagia at the bedside.

4. Yet, in some studies the water swallowing test failed to identify high risk of aspiration later proven by video fluoroscopic studies in up to a third of patients. Other bedside tests that incorporate different liquid viscosities and volumes have been proposed (such as the Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test and the Volume Viscosity Swallowing Test); they may have greater diagnostic accuracy than the water swallowing test, but they are less simple to administer (in certain hospitals, these more detailed bedside evaluations, also incorporating foods of different consistency, can be proficiently performed by especially trained therapists). Checklists for dysphagia screening have also been proposed and may be a useful addition.

5. Patients with depressed level of consciousness should not be fed by mouth until they are consistently awake, even if they passed a bedside swallow at one point in time.

6. It is essential to remember that the bedside tests rely on the evaluation of symptoms. Yet, symptoms will be absent in patients with neurogenic dysphagia who have impaired sensory innervation to the pharynx and larynx. Thus, silent aspiration cannot be excluded by a bedside swallowing test.

7. Patients who failed the bedside swallow should be kept NPO (i.e., nothing by mouth) and referred for a video fluoroscopic swallow study.

8. It is prudent to refer also for video fluoroscopic evaluation those patients who passed a water swallowing test at the bedside but have a particularly high risk for aspiration (e.g., brainstem strokes, hospitalized patients with advanced neurogenerative disorders).

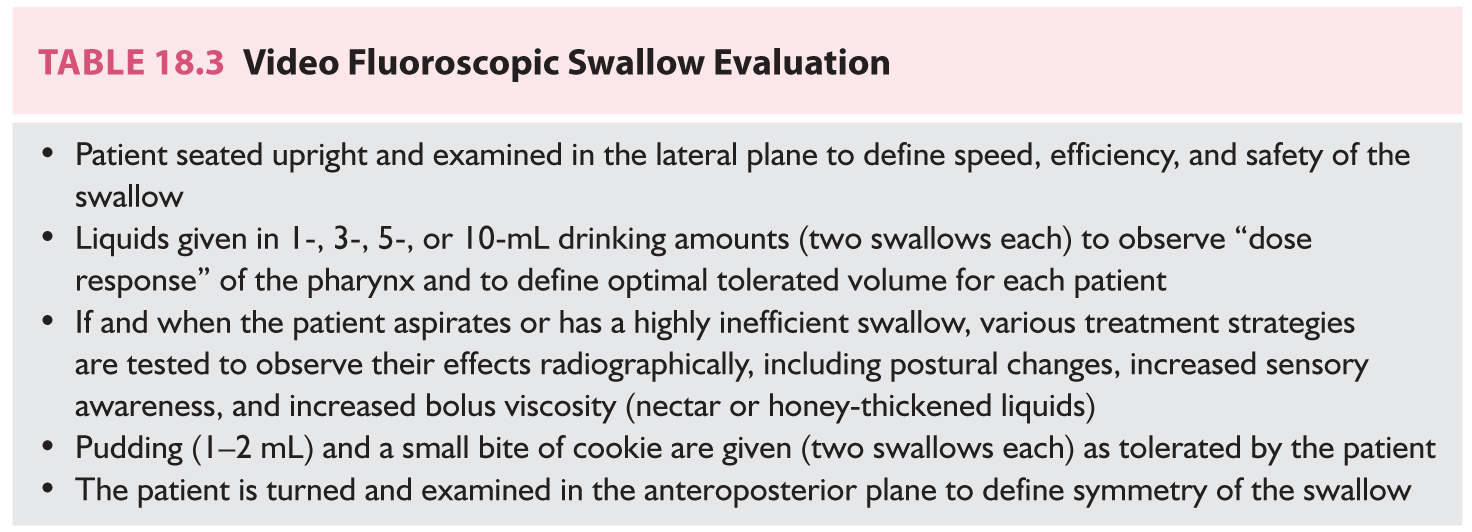

B. Video fluoroscopic swallow study.

1. The video fluoroscopic swallow study is the instrument of choice for the evaluation of dysphagia in most practices.

2. It consists of a real-time dynamic X-ray procedure performed during swallows of carefully defined radiopaque fluids and foods ![]() (Video 18.1).

(Video 18.1).

3. It allows a detailed analysis of the passage of the bolus, thus providing information to evaluate all the phases of the oropharyngeal swallowing. It also offers indirect visualization of the swallowing structures and a means to assess the outcomes of interventions that can be tried to ameliorate or compensate for the impaired functions.

4. It is typically performed by a therapist and a radiologist and the total radiation exposure averages 3 to 5 minutes. During the study, different volumes of boluses of various viscosities and consistencies are tested following a protocol designed to minimize the risk of aspiration and which is modified according to the individual characteristics of the case. In general terms, a complete study has the steps listed in Table 18.3.

5. The report should contain a description of the oral and pharyngeal anatomy and swallow physiology, the mechanisms responsible for the dysphagia, identification of the types and amounts of foods safely swallowed, whether partial or full nonoral feeding is necessary, and the effectiveness and need for compensatory strategies or swallow therapy.

6. When interpreting the report of a video fluoroscopic swallow evaluation, it is important to understand the differences between penetration and aspiration. Penetration is when the bolus enters the glottis and reaches as far as the vestibule. If the penetration takes a very short course or is very brief before being corrected, it is named “flash penetration.” Penetrated boluses should trigger unpleasant sensations from the vestibular walls prompting coughing, choking sensation, or at least tickling. Absence of these responses indicates abnormal sensation. Penetration indicates risk of aspiration. Aspiration is when the bolus actually passes the true vocal cords and can move down the tracheobronchial tree potentially reaching the lungs (most commonly bilateral basal segments, right middle lobe and lingual when the aspiration occurs while the patient is erect, and upper lobes and superior segments of the lower lobes when the aspiration occurs while the patient is recumbent or semirecumbent).

1. The fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing is performed using a flexible endoscope inserted through the nasopharynx and provides panoramic visualization of the pharynx and larynx. First the examiners should assess the general appearance of the pharynx and larynx and the movement of the vocal cords during phonation and coughing. Puffs of air are blown into the aryepiglottic folds at gradually increasing thresholds until the laryngeal adductor response is triggered. The cough reflex is by direct stimulation of the mucosa or chemical stimulation using brief inhalation of citric acid. Then swallows of different volumes, viscosities, and consistencies are tested.

2. Advantages are greater anatomical definition and direct testing of laryngeal reflexes. It is also advantageous that it can be performed at the bedside. However, it does not permit visualization of the oropharyngeal events during deglutition.

3. Other studies, such as esophageal manometry, barium swallow, and esophageal endoscopy, are necessary when esophageal pathology is suspected, but these investigations are rarely necessary in cases of dysphagia related to neurologic disease.

TREATMENT

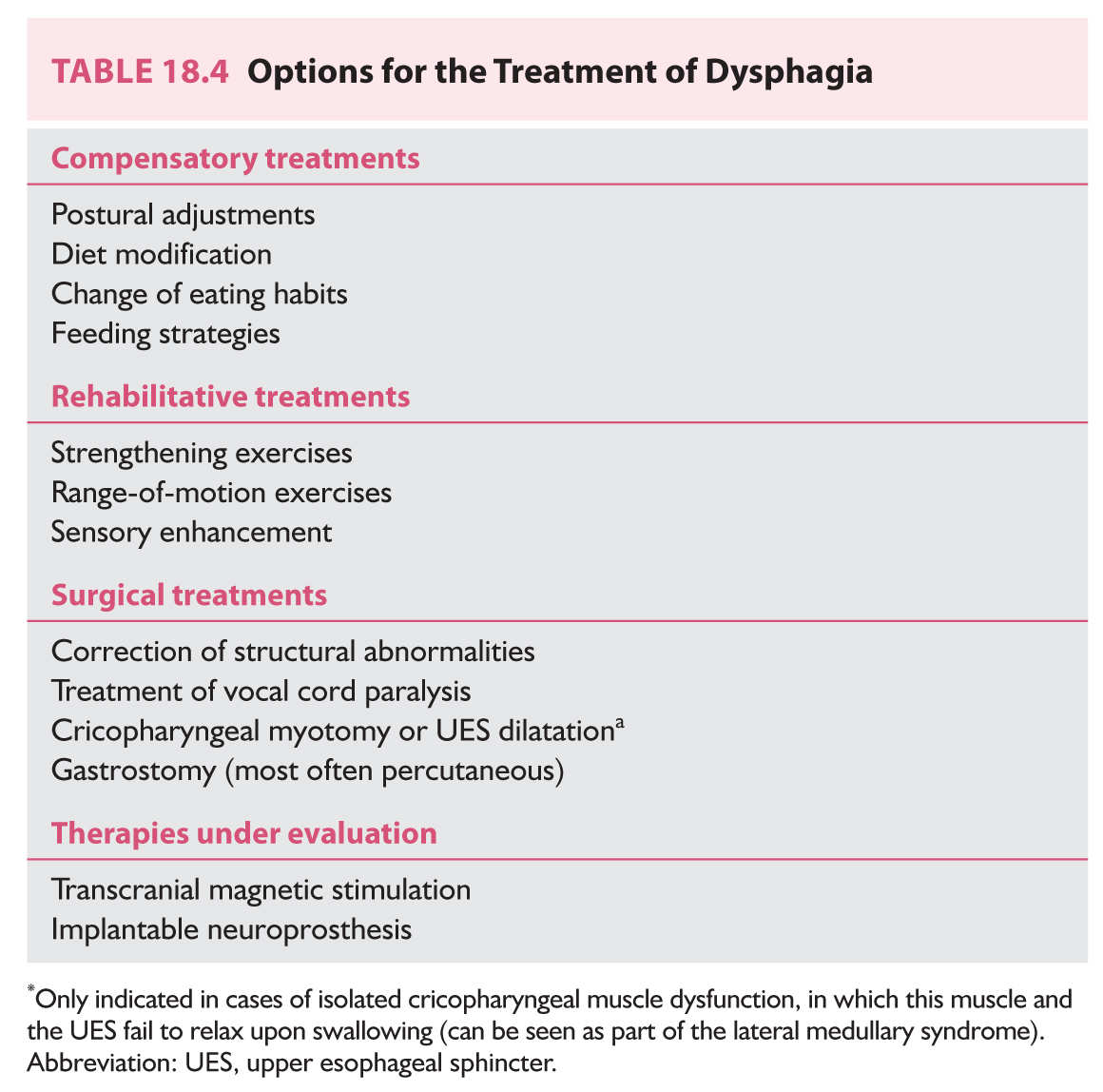

The main goal of dysphagia treatment is to minimize the risk of aspiration, maximize safe oral nutrition and hydration, and regain better quality of life, which is undoubtedly compromised in patients with dysphagia. Behavioral treatments represent the mainstay of dysphagia therapy and can be divided into compensatory and rehabilitative treatments. Surgical options (especially placement of a gastrostomy) are indicated in select circumstances and innovative treatment alternatives are being investigated. A summary list of treatment options is provided in Table 18.4.

A. Compensatory treatments.

1. These treatments are the simplest and most commonly used and consist of interventions aimed at modifying the bolus composition, its internal transit, or the conditions of food ingestion.

2. Postural adjustments. Changes in the posture to compensate for the misdirection of bolus transit. The 45-degree angle chin tuck (to slow bolus transit in patients with delayed pharyngeal trigger) is the most frequently employed. A head tilt toward the strong side may be useful in patients with hemiparesis involving the facial muscles.

3. Diet modification. Avoiding the fluid viscosities and food consistencies aspirated during video fluoroscopic swallowing evaluation. Thickened fluids (thin fluids are more frequently aspirated) and softer diets are commonly recommended, yet specific dietary modifications should be individualized based on the results of the diagnostic investigation. Patients restricted to thickened fluids must be carefully monitored for the possibility of dehydration. As the dysphagia improves, reevaluations are necessary to reincorporate more options to the diet.

4. Modification of eating habits. Education to eat slowly, moisten the oropharynx with some fluid before eating food, take small sips and bites, maintain an upright posture while drinking and eating, eliminate distractions while eating, drink fluids during the meal to wash solid residues in the oropharynx, avoid mixing fluids and solids on the same swallow, avoid talking with fluids or food in the mouth, place the food on the strong side of the mouth (if unilateral weakness).

5. Feeding strategies. Using modified cups, wide or one-way valve straws, and long spoons are some examples of useful interventions in select cases.

B. Rehabilitative treatments.

1. Strengthening exercises. Lingual resistance exercises and other focused interventions to strengthen weak deglutory muscles must be guided by trained therapists.

2. Range-of-motion exercises. Examples include a sequence of tongue movements (including elevation, lateralization, gargling, and retraction) several times per day, or the falsetto exercise (raising the vocal pitch to elevate the larynx).

3. Sensory enhancement. Most useful in patients with delayed initiation of the pharyngeal phase. Interventions can consist of applying a cold or sour stimuli at specific sites of the oropharyngeal mucosa or swallowing a cold or sour bolus.

C. Surgical treatments.

1. The main surgical intervention in patients with severe and persistent dysphagia is the placement of gastrostomy for nonoral feeding. Percutaneous gastrostomy can be safely performed at the bedside in many cases.

2. Gastrostomies are reversible and therefore it is always better to proceed with a gastrostomy in patients with dysphagia who have good prognosis for recovery but cannot eat by mouth for the time being or cannot meet caloric requirements because of swallowing difficulties or dietary restrictions. In these cases of acute and potentially reversible dysphagia, it is important to make patients and families understand that a temporary gastrostomy is a small price to pay to avoid the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

3. Instead, in patients with chronic progressive dysphagia from a neurologic disorder the decision to proceed with gastrostomy needs to be weighed carefully. In such cases the gastrostomy will be permanent and patients or their families should have a clear understanding of the goal and implications of the intervention.

4. Other surgical interventions are only applicable to very selected cases, such as those with laryngeal incompetence or isolated cricopharyngeal muscle dysfunction.

5. Surgery may be very useful to treat associated non-neurologic structural conditions that may be contributing to the dysphagia (such as Zenker’s diverticula).

D. Treatments under investigation.

1. There is interest in the application of noninvasive brain stimulation to enhance the rehabilitation of patients with dysphagia after stroke. Available information suggests that repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (ipsilateral or contralateral to the stroke) may be beneficial.

2. Implantable neuroprosthesis consisting of intramuscular stimulation of multiple hyolaryngeal muscles that can be controlled by the patient is also being investigated.

The prognosis of neurogenic dysphagia depends on the cause of the problem.

1. In stroke patients, severe deficits, bihemispheric strokes, and brainstem strokes are associated with persistent dysphagia.

2. Less severe strokes are compatible with favorable recovery and can be helped by compensatory and rehabilitative therapies.

3. In neuromuscular diseases, the dysphagia is temporary in patients with acute conditions and in those with myasthenic exacerbation. Dysphagia is irreversible and progressive in patients with muscular dystrophy.

4. In patients with progressive neurologic disorders (parkinsonian syndromes, motor neuron disease, degenerative dementias, progressive MS), the dysphagia worsens over time, generally following the pace of the primary disease.

Key Points

• Dysphagia is a common manifestation of various acute and chronic neurologic disorders putting these patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia.

• Knowledge of the normal anatomy and physiology of swallowing is necessary to understand the causes of dysphagia.

• Stroke, neuromuscular disorders, and chronic progressive neurodegenerative diseases are the main neurologic causes of dysphagia.

• A bedside water swallowing test must be performed to screen for dysphagia before oral intake not only after any stroke but also when evaluating hospitalized patients with neurologic conditions known to be associated with an increased risk of dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia.

• A video fluoroscopic study is necessary to identify silent aspiration (i.e., silent aspiration cannot be detected by a bedside swallow test).

• Compensatory and rehabilitative treatments guided by specialized therapists can improve swallowing safety in many patients with neurologic causes of dysphagia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree