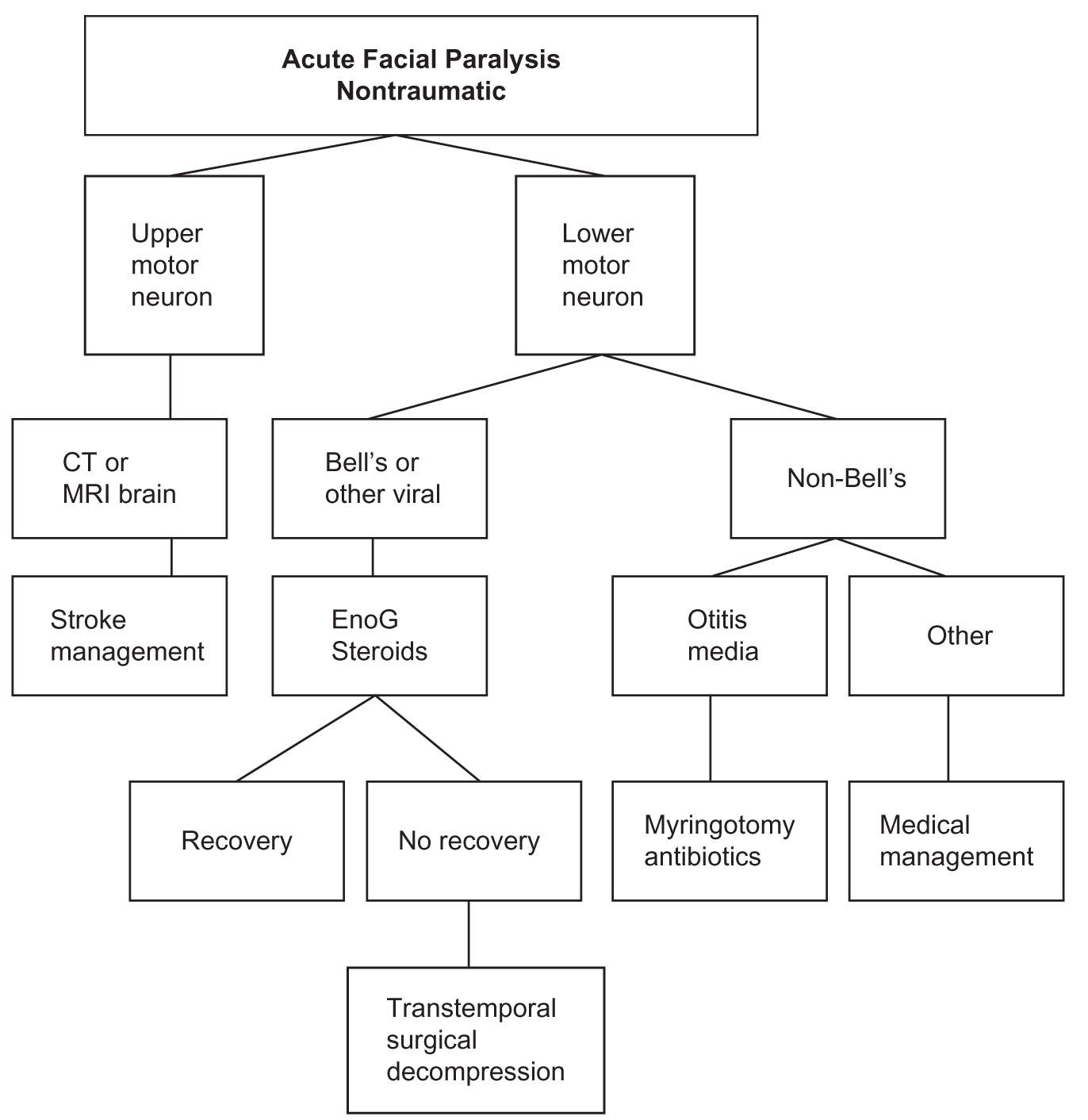

5. Audiometric testing will help determine the type and degree of hearing loss. An asymmetric, ipsilateral SNHL would suggest a cerebellopontine angle or internal auditory canal lesion in patients with LMN facial weakness. A conductive or mixed hearing loss, however, would suggest a middle ear infectious or neoplastic cause for the facial nerve deficit.

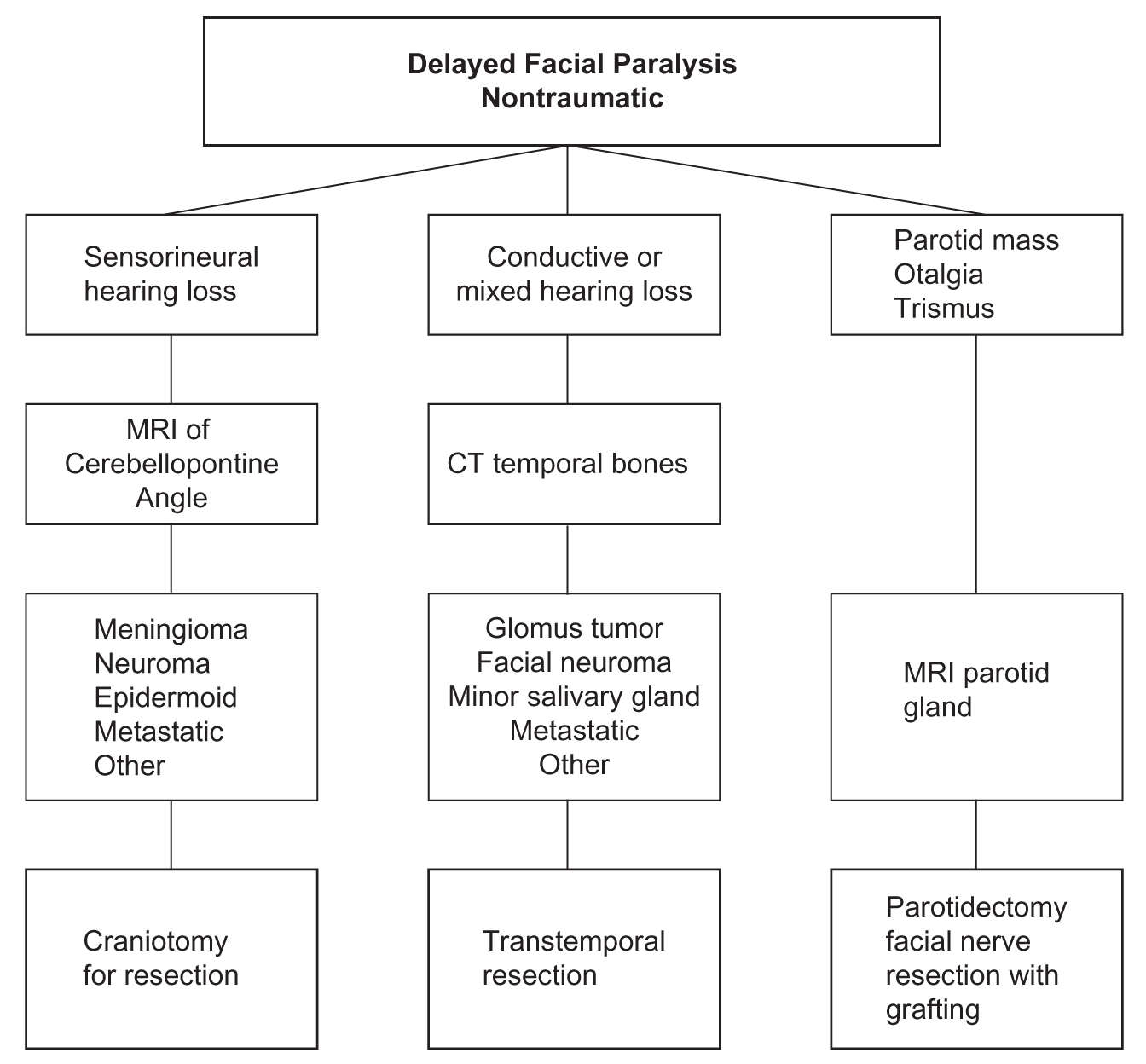

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The most common cause of peripheral facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy. This is a diagnosis of exclusion. The paralysis can be partial or complete, is unilateral, and usually occurs suddenly over 24 to 48 hours. It is currently believed to be secondary to a herpetic inflammation of the nerve. Approximately 70% of patients recover completely without treatment. Oral steroids and antiviral therapy, when given within the first 10 to 14 days after onset, may have a role in improving the ultimate patient outcome. However, recent data show that antivirals do not provide an added benefit on facial recovery.

Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus) is characterized by aural vesicles, pain, and peripheral facial nerve palsy. The vesicles can also involve the ipsilateral anterior two-thirds of the tongue and soft palate. It differs from Bell’s palsy in that vesicles are present, pain may be severe and persistent, there is a higher incidence of vestibular and auditory symptoms, and the prognosis is generally worse. The agent is believed to be varicella-zoster virus. Oral steroids and antiviral therapy are the currently accepted treatment.

Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome is characterized by recurring facial paralysis, and swelling of the face and lips, usually the upper lip. The paralysis may be unilateral or may alternate sides, and may be complete or incomplete. It can occur in males or females, usually in the second decade of life. Associated physical features also include fissuring of the tongue.

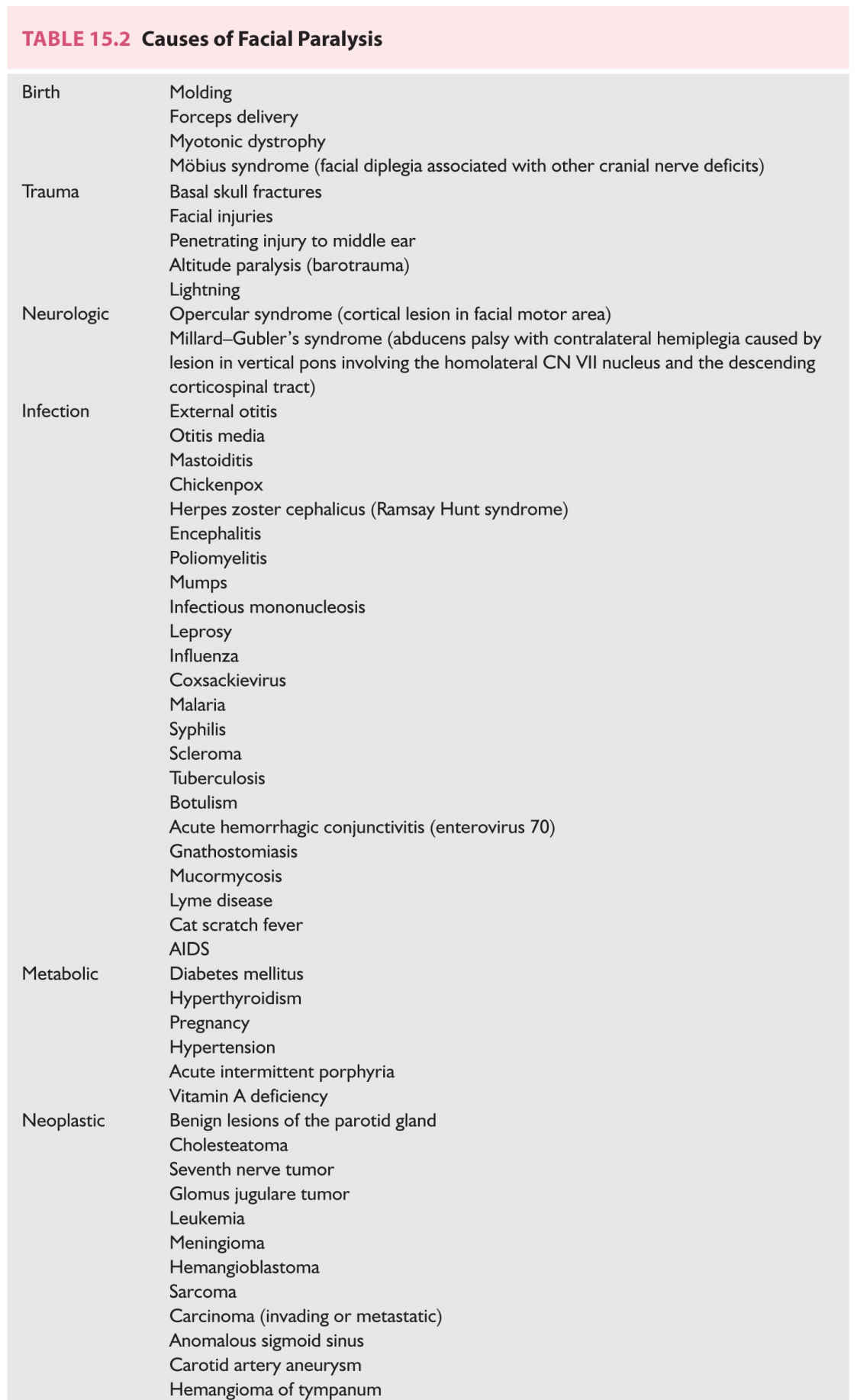

Traumatic causes for facial paralysis can be penetrating or blunt. In the patient with a penetrating injury and complete facial paralysis, the nerve should be presumed to be cut unless the facial movement on that side was clearly documented. In these cases the facial nerve should be explored and repaired as soon as the patient is medically stable.

Penetrating injury to the extratemporal, intraparotid facial nerve can be microsurgically repaired if the wound is clean, if performed as soon as feasibly possible, and if the injury involves the main trunk or a primary division of the facial nerve. Individual branch lacerations do not require surgical repair. Penetrating injury to the facial nerve within the temporal bone also requires surgical repair and, if necessary, interposition grafting with the greater auricular nerve. In the patient with a penetrating injury and complete facial paralysis, the nerve should be presumed to be cut unless the facial movement on that side was clearly documented. In these cases the facial nerve should be explored and repaired as soon as the patient is medically stable.

Iatrogenic facial nerve injury can also occur during middle ear and mastoid surgery. The tympanic segment of the facial nerve is particularly at risk during middle ear surgery such as cholesteatoma removal, in which case the bony covering of the facial nerve may be completely absent (Video 15.1). The mastoid segment of the facial nerve may be injured while removing disease in the facial recess and mastoid cavity. In these cases the nerve will usually require repair with a facial nerve graft from the great auricular nerve in the neck. ![]()

Blunt trauma to the temporal bone may cause facial paralysis as a result of neural contusion, hematoma, edema, bony impingement, laceration, or avulsion. Delayed-onset facial weakness is usually due to compression with neural edema. These patients generally recover excellent facial function without surgical or medical intervention. Acute-onset facial weakness following blunt temporal bone trauma, however, suggests more serious neural injury requiring transmastoid facial nerve decompression and repair (see Fig. 15.1).

FIGURE 15.1 Clinical assessment algorithm for patients with traumatic facial paralysis.

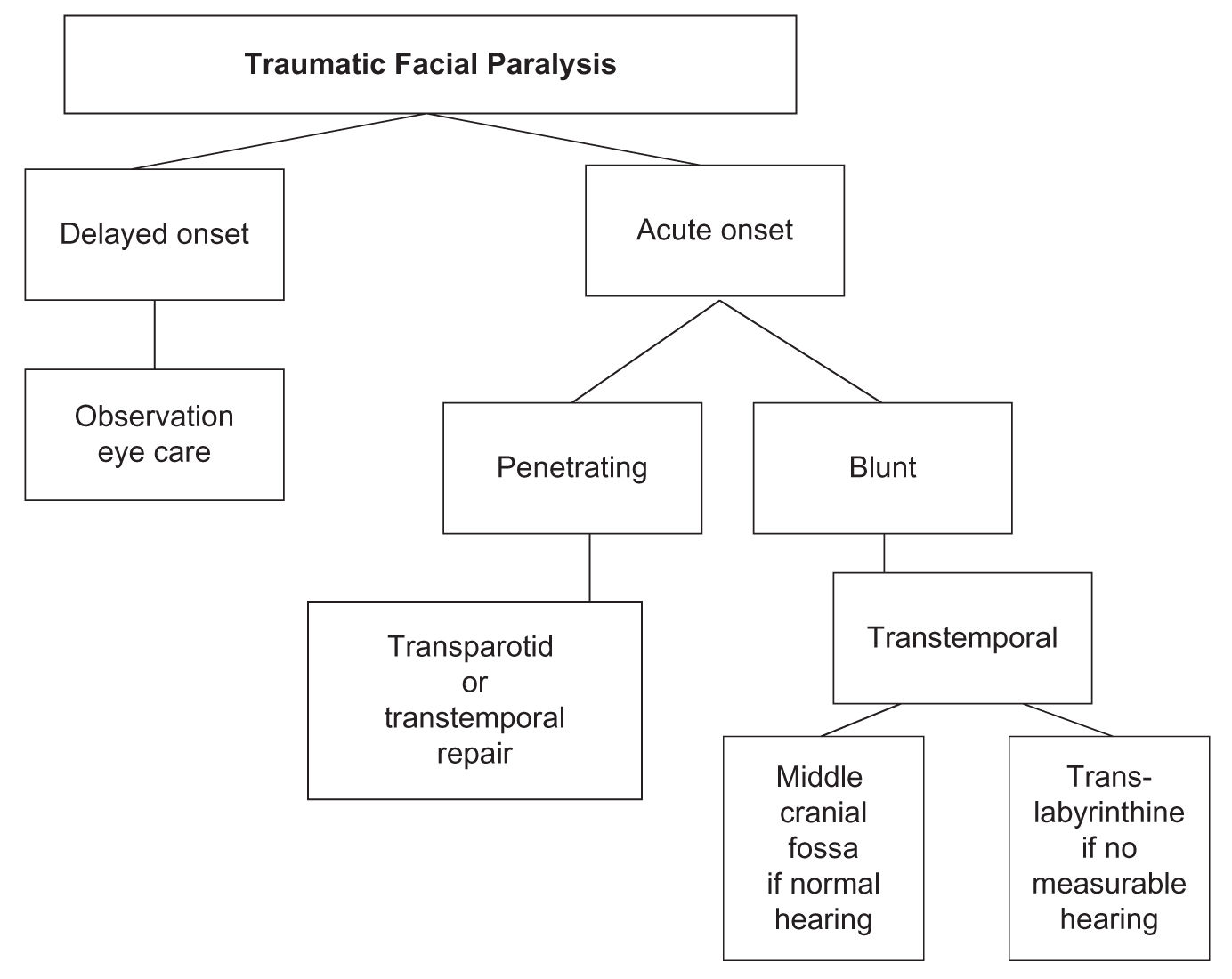

FIGURE 15.2 Clinical assessment algorithm for patients with acute, nontraumatic facial paralysis. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ENoG, electroneuronography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Congenital facial paralysis can be related to intrauterine or delivery-related trauma, facial nucleus aplasia, and facial musculature aplasia, or be associated with more complex general syndromes. Cardiofacial syndrome consists of unilateral facial palsy with congenital heart defects. Poland’s and Goldenhaar’s syndromes may occasionally be associated with facial weakness. Bilateral facial palsy with abducens nerve palsy occurs in Möbius syndrome. Myotonic dystrophy can be associated with facial palsy. An array of medical disorders, such as arterial hypertension, can be related to the onset of facial weakness.

Nontraumatic acute facial paralysis due to a stroke, brain tumor, or brain abscess can manifest as an UMN-type weakness, whereas Bell’s palsy, acute otitis media, Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), and iatrogenic injury following otologic or parotid surgery result in complete, unilateral LMN paralysis (see Fig. 15.2).

Nontraumatic, delayed facial paralysis is usually due to a neoplasm (Fig. 15.3). If the patient complains of associated hearing loss and tinnitus, the lesion is likely to be found in the cerebellopontine angle or the internal auditory canal. Slow-growing facial neuromas and glomus tumors may cause a mixed hearing loss if the tumor is isolated to the middle ear and/or mastoid bone. Malignant parotid gland tumors also cause gradual onset or segmental facial paralysis in addition to otalgia, facial pain, trismus, and bloody otorrhea (Fig. 15.4). Benign parotid gland tumors, other than intraparotid facial neuromas, rarely cause facial paralysis.

FIGURE 15.3 Clinical assessment algorithm for patients with delayed, nontraumatic facial paralysis. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

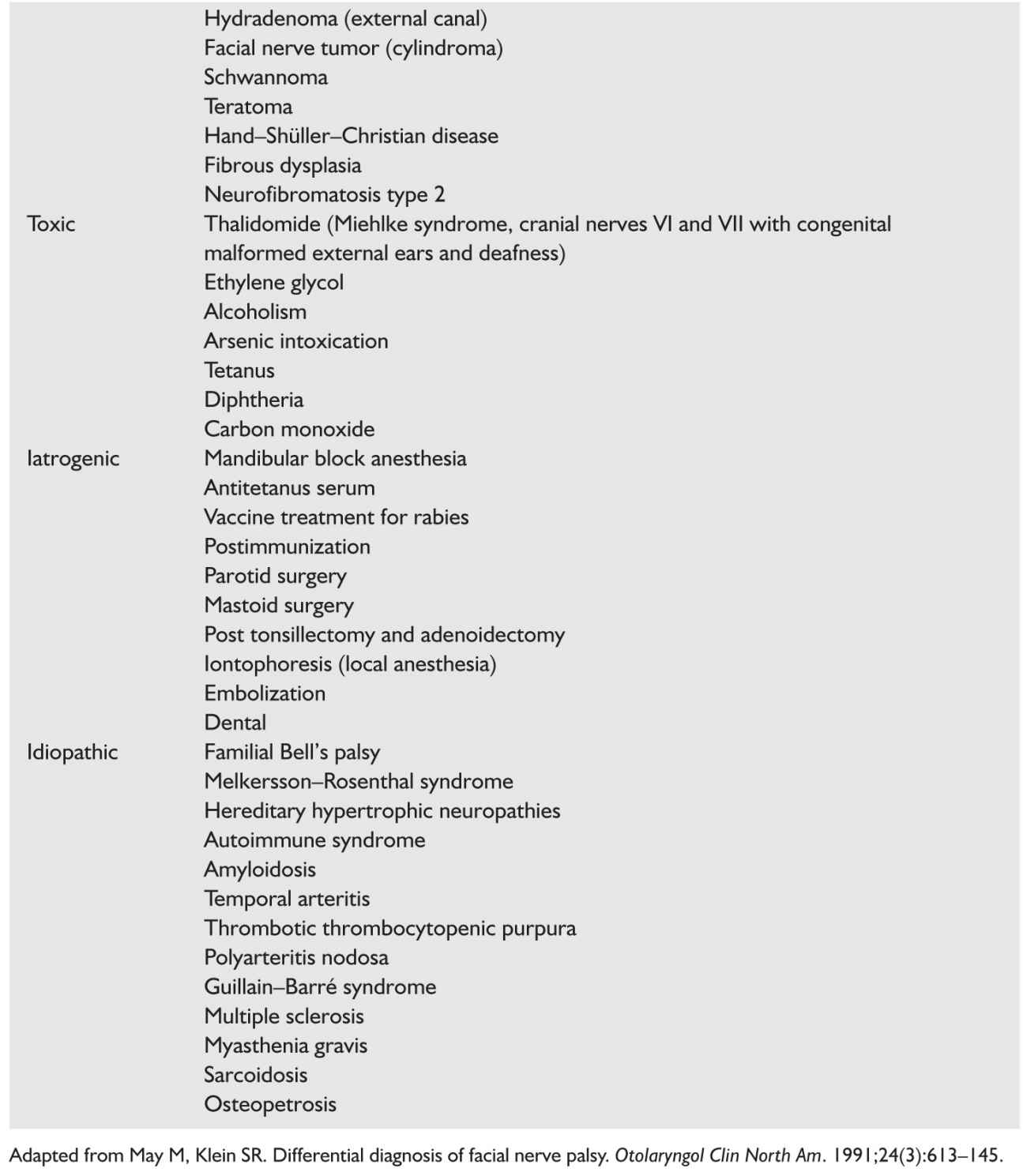

A more inclusive list of causes for facial paralysis is included in Table 15.2.

Care of the eye: A very important aspect of care of the patients with facial nerve injury is the assessment of the patients’ ability to protect their ipsilateral eye. Those who can close their eyelid completely usually do very well. Those with incomplete eyelid closure will not be able to adequately lubricate and protect their cornea. These patients may benefit from lubricant eye drops during the day and ointments such as lacrilube at bedtime. The patients can also tape their eyelid closed with paper or silk tape. Care should be taken to not put anything such as a tissue or patch on the cornea. Those patients with corneal irritation or eye pain should be seen by an ophthalmologist.

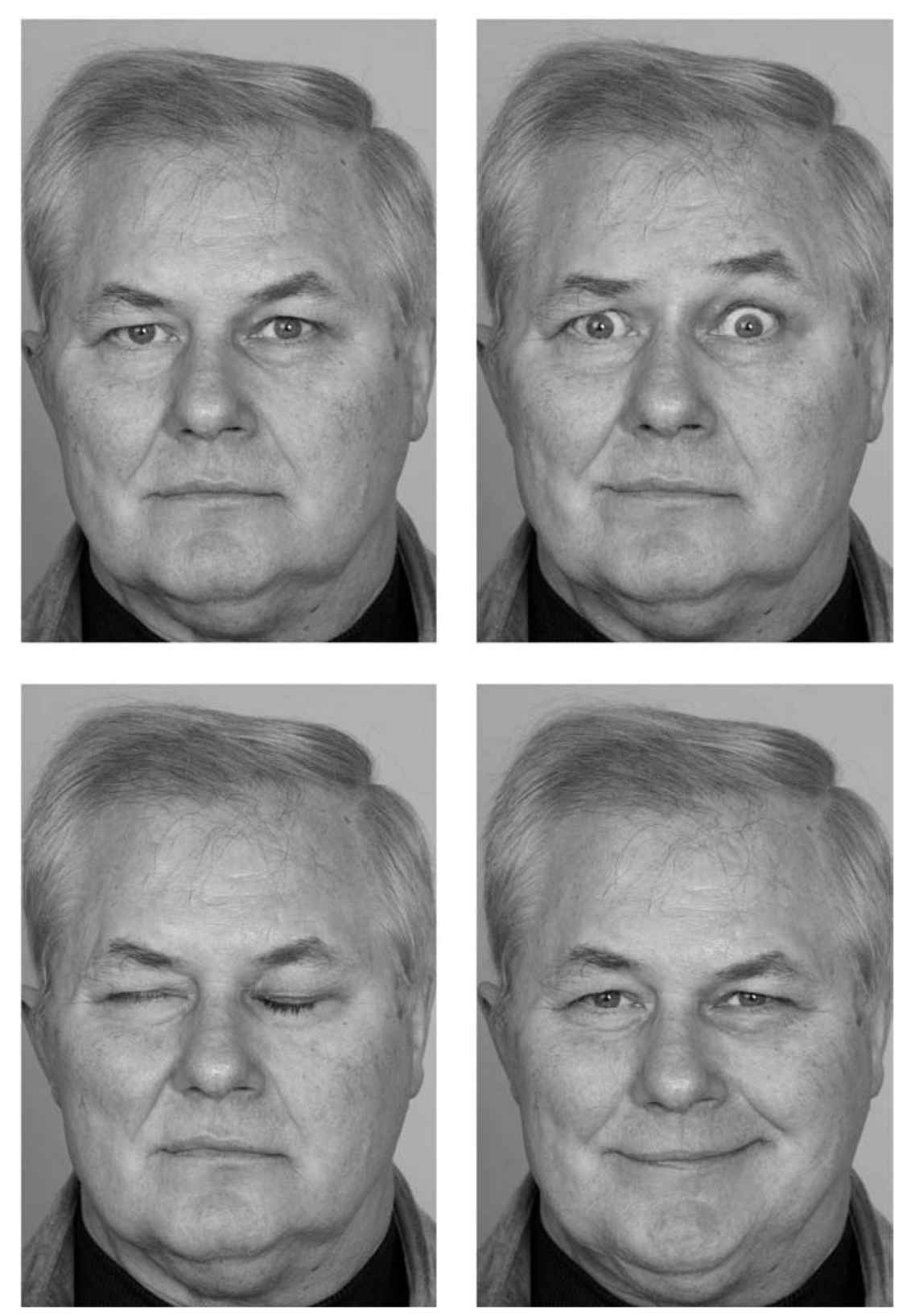

FIGURE 15.4 Long-term facial function following parotidectomy, facial nerve resection, and interposition neural grafting for acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland.

Key Points

• Bell’s palsy is the most common cause of peripheral facial nerve paralysis and has a very favorable prognosis.

• The clinical history is the most important factor in the patient assessment.

• The physical examination of the patient with facial paralysis should include otoscopy and parotid gland palpation.

• Imaging may be necessary in some patients in which the history is atypical.

• Timely diagnosis and treatment are important for maximizing facial nerve function.

• Adequate eye care for those who cannot completely close their eyelids can prevent corneal injury.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree