FIGURE 33.1 Factors that are associated with origination of a functional neurologic disorder. Predisposing factors are general factors in life that cause susceptibility. Precipitating factors trigger the onset of symptoms. Perpetuating factors prevent the symptoms from resolving and thereby induce symptoms to become chronic.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

Although there will often be clues in the history, the diagnosis of a functional neurologic disorder should be based mainly on positive signs on examination ![]() (Video 33.1). It should not be a diagnosis of exclusion. Sharing these signs with the patient is also a useful step in treatment (see section Evaluation below). Some patients are monosymptomatic for one of the problems described below. More commonly patients present with mixtures of more than one symptom. Pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and/or impaired concentration are also present in more than 50% of patients. The findings described below have variable sensitivity and specificity. They are sufficient in the hands of a neurologist to lead to a diagnosis with good stability over time but as with any physical finding are more reliable when considered in the context of the rest of the history and examination. Positive evidence of a functional disorder also does not exclude an additional comorbid neurologic diagnosis, which should always be considered. There is female preponderance for most presentations of a functional neurologic disorder, although as patients get older gender ratios become more equal. Although anyone over 5 years may develop these problems the peak age for seizures is mid-20s, and for weakness and movement disorder late-30s.

(Video 33.1). It should not be a diagnosis of exclusion. Sharing these signs with the patient is also a useful step in treatment (see section Evaluation below). Some patients are monosymptomatic for one of the problems described below. More commonly patients present with mixtures of more than one symptom. Pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and/or impaired concentration are also present in more than 50% of patients. The findings described below have variable sensitivity and specificity. They are sufficient in the hands of a neurologist to lead to a diagnosis with good stability over time but as with any physical finding are more reliable when considered in the context of the rest of the history and examination. Positive evidence of a functional disorder also does not exclude an additional comorbid neurologic diagnosis, which should always be considered. There is female preponderance for most presentations of a functional neurologic disorder, although as patients get older gender ratios become more equal. Although anyone over 5 years may develop these problems the peak age for seizures is mid-20s, and for weakness and movement disorder late-30s.

A. Functional limb weakness/paralysis.

1. Symptoms.

Functional limb weakness, or paresis, usually presents as unilateral weakness, but monoparesis and paraparesis also occur. Complete paralysis is rarer. About 50% of patients present acutely. Left-sided symptoms are not clearly more common than right. Patients may report dropping things, knees giving way, or that their limb feels alien or “not part of them.”

2. Physical examination.

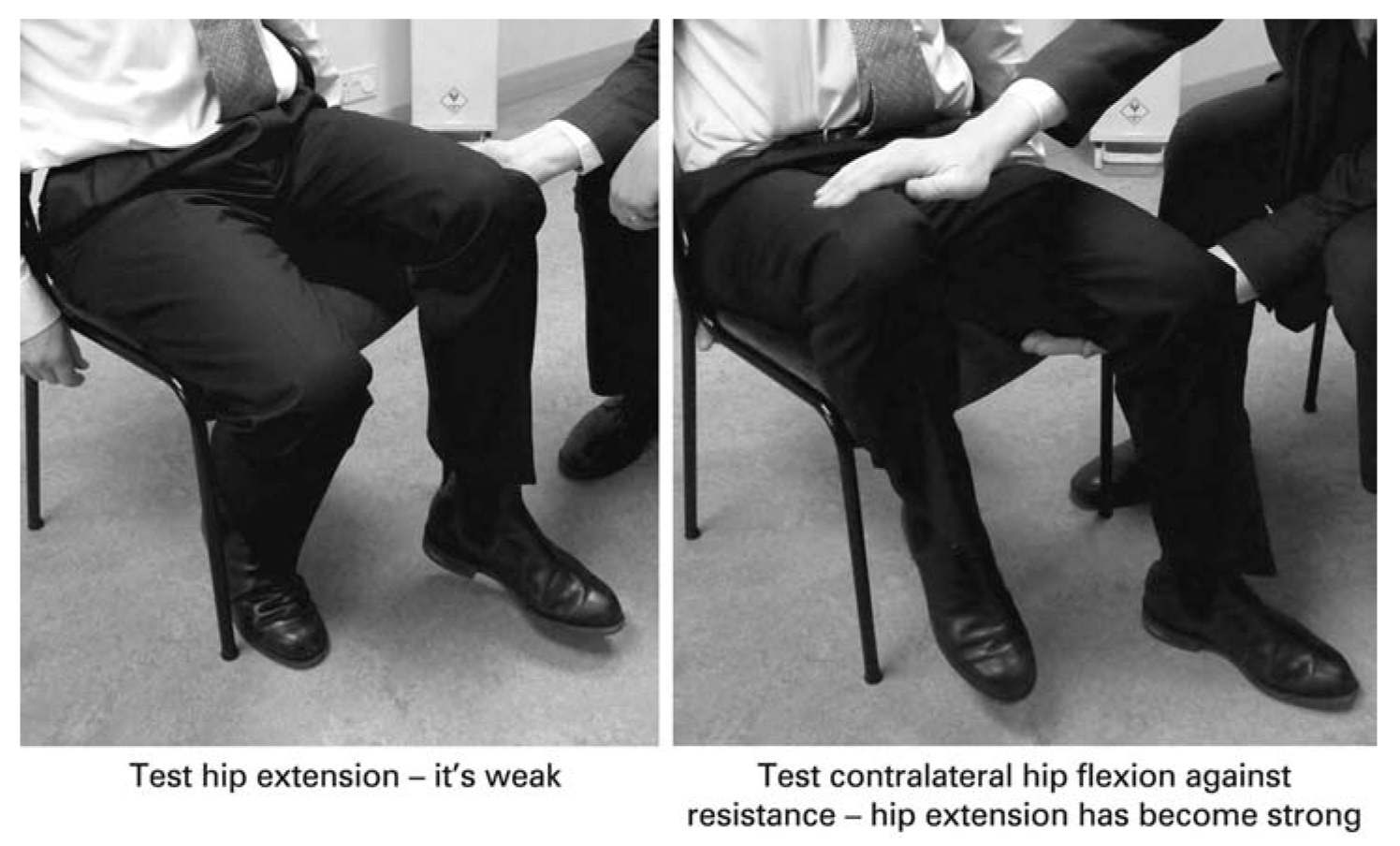

a. Hoover’s sign is positive when there is weakness of hip extension, which improves when the patient flexes their contralateral unaffected hip against resistance (Fig. 33.2). It can be performed with the patient sitting or lying. The patient may need to be asked to focus attention on the unaffected limb.

b. Hip abductor sign is similarly positive when there is weakness of hip abduction, which improves when the patient abducts their contralateral hip against resistance.

FIGURE 33.2 Hoover’s sign for functional weakness. (Adapted and reproduced by permission from Stone J. Bare essentials: functional symptoms in neurology. Pract Neurol. 2009;9:179–189.) (See color plates.)

c. Dragging gait. A typical dragging gait of functional leg weakness involves the forefoot remaining in contact with the ground rather than the circumducting gait of an organic hemiparesis. There may be internal or external hip rotation.

d. Global pattern of weakness involving flexors and extensors equally

e. Give-way weakness describes transiently normal power, which then gives way and is a feature of variable weakness.

f. Discrepancies of movement. For example, inability to plantarflex ankles but able to stand on tip toes and walk from the waiting room or inability to grip examiner’s hand compared to getting an object out of a bag.

g. Drift without pronation. There is some evidence that drift without pronation, the downward drift of an arm without the pronating movement seen in pyramidal lesions, is more common in functional arm weakness than in patients with neurologic disease.

3. Investigations.

No specific positive neurophysiologic findings although “reduced recruitment” may be seen on electromyography. Most patients require other investigations such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain and/or spine to assess for comorbid neurologic disease.

B. Functional movement disorders.

1. Symptoms. Functional movement disorders include tremor, myoclonus (jerks), dystonia (abnormal posturing), and parkinsonism.

a. Tremor. Functional tremor is characterized by variable frequency and amplitude, often subsides for certain periods, and may occur at rest, action, or posture. Tremor may be synchronous in body parts. This is in contrast to tremor in Parkinson’s disease (rest tremor), essential tremor (posture and action), or dystonic tremor (posture).

b. Myoclonus. or jerky movements. In functional myoclonus the duration of each jerk is often relatively long. Jerks that occur as a synchronous bilateral movement of both legs or in the abdomen/trunk are very likely to be functional. Jerks that start after the age of 20 and are localized in several body parts (generalized) are also relatively likely to be functional. Some patients report unpleasant prodromal symptoms, which are temporarily relieved by the jerk and/or the ability to suppress or provoke jerks (unlike myoclonus caused by neurologic disease).

c. Dystonia. is abnormal posturing of a body part. The most typical feature of functional dystonia is a fixed posture, usually a flexed arm and clenched fist or an inverted plantar flexed ankle (Fig. 33.3). This in contrast to organic dystonia, where the posturing is mobile and reversible. Pain and abnormal body schema are common in functional dystonia versus organic dystonia. Phenomenology overlaps with complex regional pain syndrome.

d. Facial dystonia. Functional facial dystonia or spasms are usually unilateral and may cause eye closure or pull the mouth or jaw to one side giving a superficial appearance of facial weakness (Fig. 33.4).

e. Parkinsonism. The combination of functional tremor (described above) and general slowness can lead to a Parkinsonian appearance.

2. Physical examination.

a. Tremor.

(1) Variable tremor frequency (variable amplitude or response to stress is not specific)

(2) Entrainment test. Ask the patient to copy, with one hand, a rhythmic movement (e.g., tapping of index finger and thumb), which the examiner varies in frequency. Positive evidence of a functional tremor arises when (a) tremor in the contralateral hand stops; (b) the tremor “entrains” to the same rhythm as the examiner or (c) the patient is unable to copy the movement.

(3) Pause with ballistic movements. For example, asking the patient to touch the tip of your finger as it is moved around in space.

(4) Distraction. Patients may have less or no tremor when they are distracted.

(5) Cocontraction of agonist and antagonist muscles may be seen.

(6) Worsening of tremor with loading or spread of the tremor elsewhere when the limb is immobilized.

b. Myoclonus. The effect of distraction can be observed in some patients (although the intermittent nature is a challenge). Long-duration jerks, especially axial jerks, favor a functional origin. Most patients previously thought to have propriospinal myoclonus probably have a functional movement disorder.

FIGURE 33.3 Functional dystonia typically presents with a clenched fist/flexed fingers (A) or inverted and plantar flexed foot (B). (Reproduced with permission from Stone J. Bare essentials: functional symptoms in neurology. Pract Neurol. 2009:9;179–189; Stone J, Carson A. Functional neurological disorders. Continuum. 2015;21:818–837.) (See color plates.)

c. Dystonia. A fixed acquired dystonia (clenched fist, inverted ankle) is characteristic but is harder to definitively diagnose unless there is resolution.

d. Facial spasms. Characteristic unilateral contraction of platysma often associated with jaw deviation or persistent unilateral contraction of orbicularis oculis (vs. transient contraction seen in hemifacial spasm or bilateral orbicularis contraction seen in blepharospasm). Tongue may deviate to the affected side also.

FIGURE 33.4 Functional facial spasm involves unilateral platysmal or orbicularis oculis contraction typically with jaw deviation and may give the appearance of facial weakness. (Reproduced with permission from Stone J. Functional neurological disorders: the neurological assessment as treatment. Neurophysiol Clin. 2014;44:363–373.) (See color plates.)

e. Parkinsonism. In addition to features of functional tremor there may be slowness without diminishing amplitude while tapping and impaired eye movements in all directions.

3. Investigations.

a. Tremor. Polymyography with tremor registration can be performed to confirm the features above. This is especially useful in long-standing functional tremor where these features may be harder to see at the bedside.

b. Myoclonus. Polymyography with back-averaging should show evidence of Bereitschaftspotential (readiness potential) before the jerk, in functional myoclonus. This may be technically difficult and depends on jerks being frequent, but not too rapidly successive. Variable pattern of recruitment of the muscles in each jerk and burst duration of over 300 also makes functional myoclonus more likely.

c. Dystonia. No additional investigations available

d. Facial spasms. No additional investigations available

e. Parkinsonism. A normal dopamine transporter–single-photon emission computed tomography scan may be useful although does not exclude a wide range of alternative “organic” extrapyramidal disorders (scans without evidence of dopaminergic dysfunction) and reminds us that the diagnosis of a functional disorder must be made on positive grounds, not because tests are normal.

C. Functional gait disorder.

1. Symptoms. Gait disorders can be caused by a movement disorder like tremor, myoclonus, or weakness in functional neurologic disorder. However, some patients do not suffer from any of those symptoms, but still have difficulties walking. Common abnormal walking patterns include ataxia-like problems with instability and/or fear of falling; gait with small steps, which may look Parkinsonian, or as if the person is “walking on ice”; ability to stand without ability to walk (abasia without astasia) or vice versa.

2. Physical examination. If unsteady while standing then the patient may improve when asked to repeat numbers drawn on their back, follow eye movement, or play a game on a smartphone. Tandem gait may appear abnormal, but in fact require good balance control to maintain the adopted posture. Walking may improve with encouragement such as fingertip support from the examiner, or normalize when the patient is asked to walk backwards or adopt a “skating” motion. Caution is warranted in diagnosing gait disorder as functional because it is “bizarre,” as many “organic” movement disorders, for example, chorea or dyskinetic gait in Parkinson’s disease can be “bizarre.”

D. Dissociative/Psychogenic (nonepileptic) attacks/seizures.

1. Symptoms. Dissociative attacks or seizures (terminology from ICD-10) present with episodes with jerking and unresponsiveness or events in which there is motionless unresponsiveness (either falling to the ground lying still or absence-like states). In this context dissociation describes the patients’ experience of losing awareness and having amnesia for an event, regardless of whether they experience dissociative symptoms.

a. Aura or warning symptoms are present in more than 50% of patients, at least some times although patients are often reluctant to describe them. Commonly there is a mixture of symptoms of autonomic arousal (feeling hot, clammy with a tight chest, and altered breathing) combined with dissociative symptoms, the feeling of being detached from yourself (depersonalization) or the world around you (derealization). This may be described as feeling “not there,” “feeling far away,” “disconnected,” or “spaced out.” There may be panic and fear, but particularly in patients with many attacks, no fear, but nonetheless an unpleasant, “horrible” or “unbearable” feeling that precedes the attack. In some patients the attack itself comes as a relief of this distressing feeling. In many patients no warning symptoms are discernible or the warning signs have stopped.

b. Generalized shaking attacks, with hyperkinetic limb movements, typically tremor rather than clonic movements

c. Sudden motionless unresponsiveness episodes resembling syncope.

d. Blank spells resembling absence seizures.

2. Physical examination. As with all attack disorders, the initial diagnosis should be suggested with a witness history, preferably supplemented with a home video, which makes the diagnosis more reliable. A sudden fall to the floor with motionless unresponsiveness and eyes closed for more than 2 minutes is a dissociative attack unless proven otherwise. Specific features of dissociative seizures include long-duration attacks (more than 3 minutes) (compared with tonic-clonic epileptic events that typically last 60 to 90 seconds); closed eyes +/− resistance to eye opening (vs. eyes open in epilepsy); ability to recall generalized shaking; crying directly after the attack; side-to-side head movements; tremor-like asynchronous movements and hyperventilation (vs. clonic movements and apnea in epilepsy). Features that do NOT distinguish dissociative and epileptic seizures well include falls and injury, urine incontinence, breath-holding spells leading to desaturation, tongue biting, and seizures that arise from sleep.

3. Investigations. Video electroencephalography (EEG) during an attack is the gold standard. There should be typical semiology of a dissociative attack recorded during the EEG. In epilepsy there will be typical clinical features of epilepsy accompanied by epileptiform abnormalities on EEG. The semiology is crucial though, for example, surface EEG can be normal in frontal lobe epilepsy or epilepsy with a deep focus.

E. Functional sensory symptoms.

1. Symptoms. Hypersensitivity, numbness, tingling, and loss or altered proprioception can occur. Patients with limb weakness may report circumferential numbness at the shoulder or top of the leg. Hemisensory disturbance is also a common pattern. Dense sensory loss to all modalities including pain is sometimes striking.

2. Physical examination. Positive sensory signs of a functional disorder on examination (e.g., midline splitting of vibration sense) are not specific, although may be more so if the sensory disturbance is dense. Typically mild functional weakness is also present.

3. Investigations. Somatosensory evoked potentials may be useful in patients with dense sensory loss.

F. Speech symptoms.

1. Symptoms. Functional dysphonia presenting with a whispering speech is the commonest type. Acquired onset of stuttering in adulthood is often functional in nature. Less commonly patients may present with telegrammatic speech omitting conjunctions, prepositions, and definite articles, a foreign accent syndrome or mutism.

2. Physical examination. Variability is the hallmark. Resolution under hypnosis or sedation can also help to positively identify the problem.

3. Investigations. Assessment of variability in speech is best assessed by a speech pathologist who can recognize internal inconsistencies. Foreign accent syndrome can occur from organic brain lesions.

G. Visual symptoms.

1. Signs and symptoms. More commonly seen by ophthalmologists than neurologists. Symptoms include impaired vision, blindness, intermittent blurred vision, and altered visual fields including tunnel vision and diplopia.

2. Physical examination. Patients with functional blindness may have difficulty signing their name or touching their index fingers in front of their face. Unilateral visual loss or impaired vision can be positively diagnosed as functional using tests such as a fogging test in which lenses of progressive opacity are placed in front of the good eye until vision can be demonstrated to occur in the affected eye. A tubular visual field (the same width at 1 and 2 meters) is evidence of a functional visual field deficit (organic visual fields expand conically). Functional diplopia is associated with convergent spasm, which can sometimes look like a sixth nerve palsy.

3. Investigations. Cortical blindness should be considered in someone with limited “blindsight.”

H. Cognitive symptoms.

1. Symptoms. Not strictly part of Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder (DSM-5 ) but common in association with other symptoms. Memory symptoms range from impaired concentration and memory as seen in depression and anxiety to profound retrograde amnesia lasting years. Language problems such as using the wrong word or spoonerisms are often reported by patients. Executive impairments are commonly found on formal testing.

2. Physical examination. Patients may perform poorly on tests of attention and executive function with “blanks” in their performance. Marked retrograde amnesia in the presence of normal anterograde memory or disproportionate loss of memory for personal identity is usually functional/psychogenic. Cognitive “effort” tests can be useful at identifying patients who are performing at or below chance. In a legal setting this should increase suspicion of malingering.

3. Investigations. Functional cognitive symptoms are common but clinicians should be wary of patients presenting in the prodrome of neurodegenerative conditions.

I. Dizziness. Chronic subjective dizziness, also called phobic postural vertigo or persistent perceptual postural dizziness (PPPD), describes a fairly common group of patients who present with disequilibrium and increased focus on bodily movement and sensation without evidence of vestibular or neurologic disease. They have usually experienced vertigo because of migraine, minor head injury, or a transient vestibular pathology, which has become persistent as part of a functional disorder. Additional anxiety and dissociative symptoms are common.

EVALUATION

The neurologic evaluation of patients with a functional neurologic disorder can itself be the beginning of treatment.

A. History.

1. List of all symptoms. It is both informative and potentially therapeutic to make a list of all current physical symptoms including fatigue, sleep, concentration problems, and dizziness.

2. Day-to-day functioning. What does a normal day look like? Patients often focus on what they cannot do, but try to establish what they actually spend time doing. This provides clues about anxiety and mood disorders.

3. Symptom onset. Symptoms or events at onset can be helpful in later explanation of mechanism (e.g., minor injury or a panic attack leading to unilateral attentional focus). We would suggest, however, leaving questions about life events or trauma for later assessments unless volunteered by the patient.

4. Illness beliefs. What does the patient think is wrong? Any particular conditions they were wondering about? Discuss previous medical experiences and their expectations of treatment. Are they motivated to change? This helps tailor your explanation and onward referral to meet the patients’ concerns.

5. Discussing anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric symptoms. Although these are common they are not universal and not necessary in order to make a correct diagnosis. This patient group is typically sensitive to the idea that they are faking the symptoms or that the symptoms might be a result of them having a psychiatric disorder. Physical symptoms and day-to-day activity often strongly suggest psychological comorbidity. If asked directly it is often better to ask “Do your symptoms make you anxious?” rather than “Do you have anxiety?”.

B. Physical examination. The diagnosis of a functional neurologic disorder rests on demonstrating positive physical signs on examination (described above).

C. Investigations. It is not a diagnosis of exclusion or a diagnosis made by performing multiple negative tests. Investigations will usually be necessary, but the purpose is to look for comorbid neurologic disease, not to disprove a clinically definite diagnosis of a functional disorder. Studies show that anticipating negative results, and discussing the potential for incidental abnormalities (such as high-signal T2 lesions on MRI brain) or changes that are simply normal for age (degenerative disease of the spine) are helpful for later understanding.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In principle all neurologic disorders could be listed as a differential diagnosis of functional neurologic disorders. We, therefore, discuss common issues and diagnostic pitfalls. Misdiagnosis occurs in less than 5% of patients in studies, which is the same rate as for other neurologic and psychiatric disorders.

A. Factitious disorder and malingering are defined at the start of this chapter. Clues to either are listed below. Some patients exist on a spectrum between a genuine functional disorder and willful exaggeration.

1. Major discrepancy between reported and observed function (i.e., seen jogging when they had reported requiring a walking aid). Note that a discrepancy between reported symptoms (e.g., telling a doctor they have 10/10 severity pain but relatively normal day-to-day function) is not evidence of willful exaggeration but a common feature of functional disorders.

2. Evidence of previous lying to health professionals.

3. Obvious financial incentive (e.g., a legal case). Most patients in legal cases have genuine disorders but this situation should encourage greater scrutiny of the possibility of willful exaggeration.

4. Failure of cognitive effort testing. Examples of this are scoring a) well below chance or b) lower than someone with severe dementia. Even here it can be argued that patients may subconsciously aim to fail a test in order to demonstrate their complaints to a health professional.

Arguments against willful exaggeration as an explanation for the vast majority of patients include similarity of patient experiences across countries and across time; clustering of typical symptoms including pain, anxiety, cognitive symptoms, and fatigue; strong desire for investigations in many patients; response to treatment when delivered with expertise; persistence of symptoms on long-term follow-up in a high proportion of untreated patients.

B. General diagnostic pitfalls.

1. Assuming that a functional disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion. It is not, it requires positive evidence for a diagnosis and can be diagnosed in a patient with a neurologic disease.

2. Forgetting to look for comorbid neurologic disease. Disease is a strong risk factor for functional disorders. Patients in the early stages of neurodegenerative diseases, especially Parkinson’s disease, may present with functional symptoms that are disproportionate to their developing pathology.

3. Assuming that because something is bizarre it is functional. Many neurologic diseases look bizarre, for example, “sensory tricks” in focal dystonia, bizarre axial posturing in clear consciousness during frontal lobe seizures, or chorea.

4. Placing too much weight on psychiatric comorbidity, abnormal personality traits, stress. All of these are common in neurologic disease and may be absent in neurologic disease.

5. Assuming that a patient who is male, older, or appears to be psychologically “normal” cannot have a functional disorder. They can!

6. Assuming that long-standing diagnoses such as epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, or stroke are correct.

7. La belle indifference. This refers to cheerful indifference to neurologic impairment has often been cited as evidence of a functional disorder. Studies show it has no diagnostic value and is common in patients with frontal lobe disorders. When present in a functional disorder it typically represents a patient “putting on a brave face” to avoid anyone thinking they are distressed or low in mood.

8. Secondary gain. This refers to the benefits of being ill, and occurs in patients with functional disorders (when it is often a focus of attention by the clinician) and disease (where it is often overlooked). It has never been convincingly demonstrated to be a specific feature in this patient group.

9. Attributing symptoms incorrectly to minor radiologic or laboratory test abnormalities in the presence of clear evidence of a functional disorder. For example, degenerative changes are universal in the population over 40 and high-signal lesions become more common as people age.

C. Motor symptoms. Specific pitfalls include the following:

1. Tics. Tourette syndrome normally begins in childhood and can be voluntarily suppressed.

2. Orthostatic tremor. Tremor only when standing often with gait abnormality. Patients feel the tremor, but it does not always present visibly.

3. Axial (propriospinal) myoclonus. Is mostly functional, but can be caused by spinal abnormalities.

4. Higher cortical lesions, for example, parietal stroke. Problems such as inattention or neglect may present with apparent inconsistent symptoms or unusual gait.

5. Stiff person syndrome and autoimmune encephalitis. These are examples of neurological conditions associated with a high rate of psychiatric symptomatology, and variable and sometimes bizarre symptoms, which can obscure the neurologic diagnosis.

6. Urinary retention in a patient with weak legs. This should always be investigated but in many cases appears to relate to a combination of acute pain, opiates, and a functional disorder.

D. Seizure symptoms. Specific pitfalls include the following:

1. Frontal seizures. These often look strange with axial twisting movements, including pelvic thrusting, verbalization, and hard-to-characterize hyperkinetic movements. Surface EEG may be normal. They are, however, typically very brief.

2. Temporal lobe seizures. These can last several minutes and may be associated with ictal fear and dissociation that make them appear clinically similar to panic or dissociative attacks.

3. Self- or stress-induced epilepsy.

4. Atypical features of dissociative nonepileptic seizures. These include olfactory hallucinations, physical injury, tongue biting, incontinence, and desaturation (because of breath holding).

5. Response to anticonvulsants. This does not necessarily indicate a diagnosis of epilepsy and “therapeutic trials” should be avoided for this reason.

TREATMENT BY THE NEUROLOGIST AND ONWARD REFERRAL

The prognosis is often poor when left untreated for functional motor and seizure disorders.

A. The role of the neurologist. The neurologist, as the doctor who usually makes the diagnosis, has a central role in treatment. This includes explaining the nature of the disorder to the patient, providing follow-up and coordinating onward care.

B. Why neurologist attempts at treatment fail. Communication of the diagnosis and treatment of a functional disorder may go wrong in neurologic settings for many reasons including delay in considering the diagnosis failure to name the disorder (either by giving no diagnosis or simply telling the patient the conditions they do not have); failure to explain the rationale for the diagnosis and that it is not a diagnosis of exclusion; jumping too quickly to speculative discussions of etiology, for example psychological factors that are then interpreted by the patient as an accusation of faking the symptoms and failure to offer a rational program of treatment. Failure at this stage normally means that other health professionals will be unlikely to help the patient.

C. Using the normal model of neurologic treatment. Communication of the diagnosis works best when physicians stick to the normal model use in any other consultation. Name the disorder, explain the rationale (in the case of functional disorder, the positive clinical signs), and something about the mechanism (a problem with nervous system functioning or “dissociation”) but leave discussions about etiology for later (as we do for most neurologic disease) and take responsibility for onward treatment—it is unlikely anyone else will if the neurologist does not.

D. Elements of successful diagnostic communication.

1. Name the diagnosis (tell them “You have a Functional Movement Disorder with Dissociative attacks”). Avoid an initial focus on telling the patient what they do not have. Although at some stage this will be helpful this is not what we do for other disorders (e.g., “You have migraine” comes before “You do not have a brain tumor”).

2. Underline that this diagnosis is common.

3. Tell the patient you believe him/her. Patient with a functional neurologic disorder often have the feeling physicians do not believe their symptoms are real. Explicit discussion that the symptoms are genuine can help.

4. Explain the rationale for the diagnosis. Convincing the patient that the diagnosis is correct is not something trivial: patients have often seen many physicians before you and may be skeptical that no scans or blood tests are needed to make this diagnosis. We would strongly suggest sharing the positive clinical signs with the patient. For example, demonstrate Hoover’s sign in limb weakness or entrainment in tremor. This needs to be done supportively to demonstrate unequivocally that this is a clinical diagnosis in which normal functioning is still, transiently, possible and therefore the disorder is potentially reversible.

5. Explain the mechanism. “It is a problem in the functioning of the nervous system. Nothing is damaged, but it is not working properly.” For seizures: “You are having episodes in which you are spontaneously going into a trance like state called dissociation.” You can use metaphors like “It is a software problem, not a hardware problem.”

6. The symptoms are potentially reversible if there is active participation from the patient. Recovery is possible as there is no damage to the nervous system; however, there is no magic quick fix. Patients need to relearn normal functioning. Active involvement of the patient is essential for that. “These attacks have developed as an involuntary habit. You’ll need help to learn how to retrain out of this habit. Treatment can help you retrain the brain to change these habits”.

7. Provide self-help information. For example, www.neurosymptoms.org, http://www.nonepilepticattacks.info

8. Send the patient a copy of your clinic letter. To ensure transparency and to maximize the patient’s understanding

E. Second neurologic consultation. A second visit allows an assessment of the patients’ understanding of a complex diagnosis that they are unlikely to have previously heard of and their motivation to read self-help material. This in turn influences further management. Patients with good understanding and motivation are more likely to benefit from further treatment. Those with little understanding who cannot repeat back any information or who disagree with the diagnosis probably will not benefit. Patients with a positive experience from the first visit will often disclose additional relevant information at a second visit.

F. Triaging and coordinating further treatment.

1. First-line treatment. Explanation and provision of self-help, simple rehabilitation advice, and follow-up by a neurologist

2. Second-line treatment. Should be offered to patients who have engaged with their diagnosis and are motivated for treatment

a. Functional movement disorders including limb weakness. Referral to a physiotherapist with expertise in functional motor disorders. Physiotherapy techniques differ from those used in stroke or multiple sclerosis, are well described, and show benefit in randomized clinical trials. A skilled physiotherapist will use treatment to reinforce the rationale for the diagnosis and incorporate graded exercise and cognitive behavioral techniques for symptoms such as fatigue and pain.

b. Dissociative (nonepileptic) seizures. Referral for education and psychotherapy. The best evidence is for cognitive behavioral therapy.

3. Third-line treatment includes multidisciplinary inpatient treatment, hypnosis, therapeutic sedation (which may be particularly relevant for patients with functional dystonia), and psychodynamic or other types of psychotherapy. There is no evidence for pharmacotherapy although comorbid depression and anxiety or pain can be treated in the usual way.

• Diagnose a functional neurologic disorder primarily on positive examination signs such as Hoover’s sign or the Tremor Entrainment sign, not by exclusion.

• The diagnosis should not be made just because tests are normal, the presentation is bizarre, or there is psychosocial comorbidity.

• The neurologist has a key role in explaining the diagnosis, preferably by sharing positive evidence of the diagnosis and providing written information.

• Further treatment involves both physical and psychological therapy but this is dependent on a successful neurologic consultation.

• Current models encompass both neurologic factors (e.g., abnormally focused attention, amplification of physiologic stimuli) and psychological factors (e.g., “top down” beliefs and emotional dysregulation).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree