22.1).

(3) C7 radiculopathy (C6–C7 disk herniation). This is the most common disk herniation. Pain radiates across the top of the neck, across the triceps, and down the posterolateral forearm to the middle finger. Numbness again is more distal. A weak triceps and reduced triceps reflex are observed.

(4) C8 radiculopathy (C7–T1 disk herniation). This is very uncommon. Pain and numbness radiate across the neck and down the arm to the small finger and ring finger. Wrist flexion and the intrinsic muscles of the hand are weak.

3. Radiographic evaluation.

a. Plain X-rays provide very little help. They may show slight narrowing of the disk space involved and loss of lordosis.

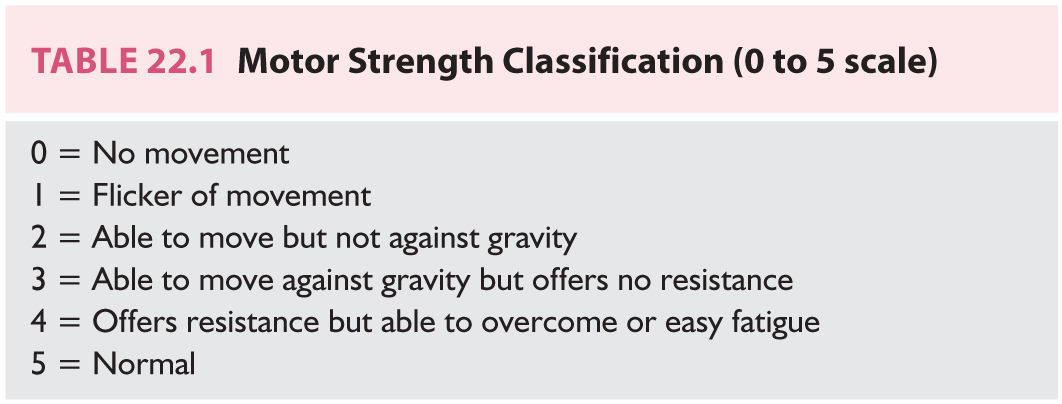

b. MRI scan without contrast is the study of choice for demonstrating a soft cervical disk herniation (Fig. 22.1).

FIGURE 22.1 Sagittal and axial MRI image demonstrating a large eccentric C5–C6 cervical disc herniation causing a left C6 radiculopathy.

4. Electromyogram and nerve conduction studies (EMG/NCS). An EMG for a single-level disk herniation with a radiculopathy is not absolutely necessary. An EMG can help when other disorders, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and brachial plexopathy, need to be ruled out.

D. Referral.

1. Physical therapy. After diagnosis by MRI, a patient with a motor strength rating of 4/5 or more (Table 22.1) can be referred for cervical traction, heat, ultrasound, massage, and a soft collar. Initially, cervical traction should be done by a physical therapist. Inform the therapist that if traction is tolerated; the patient is to be instructed in home cervical traction at 10 lb for ½ hour every night. Approximately 60% to 80% of soft disk herniations improve to the point of resolution of the radiculopathy with traction alone within 4 to 6 weeks. Not every patient can tolerate traction.

2. Medications. A trial of 4 mg self-weaning methylprednisolone (Medrol) dose pack can be used early in the treatment prior to nonsteroidals with some success. Other medicines were previously discussed in the section on traumatic neck pain.

3. Time-off from work. Desk-type workers with mild to moderate neck/arm pain can work, and most ambitious people are able to function. Heavy laborers may benefit from light duty or 1 to 4 weeks off work. Beware of patients who exhibit symptom magnification and functional overlay for purposes of secondary gain (worker’s compensation and litigation). They have the tendency to abuse time off work. In these scenarios, early referral to a PM&R specialist may be helpful.

4. Spine specialist. In any patient with three-fifth strength or worse, immediate referral to a spine surgeon is indicated. The longer a root is compressed with severe weakness, the less likely strength will return to normal. If the strength remains four-fifth or better but pain persists after 3 to 6 weeks of traction, then referral to a spine surgeon is also indicated. A well-trained spine surgeon should achieve improvement of arm pain and weakness in 90% to 95% of soft cervical disk herniations.

NECK PAIN WITH ARM PAIN FROM BONE SPURS (HARD DISC, CERVICAL SPONDYLOSIS)

A. Introduction. The combination of neck pain and arm pain in cervical spondylosis is also of epidemic proportions in the elderly population.

B. Etiology. Disk dehydration and narrowing lead to bone spur formation at the margins of the vertebral body. The spurs can project into the foramen or canal, compressing the nerve root or the spinal cord, or both. In addition, facet arthritis with resultant hypertrophy and ligamentous hypertrophy also narrow the spinal canal and neural foramina. With progressive age, more than one disc space is usually involved. The center of the process usually extends from C4 to C7.

C. Evaluation.

1. History. This condition occurs primarily in patients older than soft cervical disk herniation patients, although the two groups overlap. About 90% of patients have gradual onset of neck pain with progression to neck and arm pain. The pain radiates down the shoulder and into the arm. There are some dermatomal patterns of radiation that can help discern the level of root compression. Various complaints of suboccipital headache, interscapular pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness may also be present. The pain often wakes the patient up from sleep. About 10% of patients have asymptomatic degenerative arthritis, and then symptoms of neck pain/arm pain are often precipitated by hyperextension/flexion injuries from trauma (motor vehicle accidents). A large percentage have multiple disk spaces involved, making it more difficult to determine which level or levels caused the radiculopathy.

2. Physical examination.

a. Neck examination. There is posterior tenderness, especially tenderness at the spinous process near the level of involvement and paracervical tenderness. Painful limitation of motion with extension and lateral gaze to the side of arm pain is classic.

b. Arm examination (see Table 22.1) same as discussed in soft cervical disc section.

c. Leg examination (Table 22.2). Gait is usually normal even in the face of significant radiographic evidence of spinal cord compression. Occasionally, myelopathy is present. Early on, the gait is normal in the face of increased muscle stretch reflexes and a Babinski sign. With more severe and prolonged compression, one can observe spastic gait with bowel and bladder problems. In the most severe cases, the patient requires a cane or a walker. Rarely is it allowed to progress to wheelchair dependency.

3. Radiographs.

a. Plain X-rays show disk space narrowing with osteophyte (bone spur) formation. Oblique films can exhibit neuroforaminal narrowing.

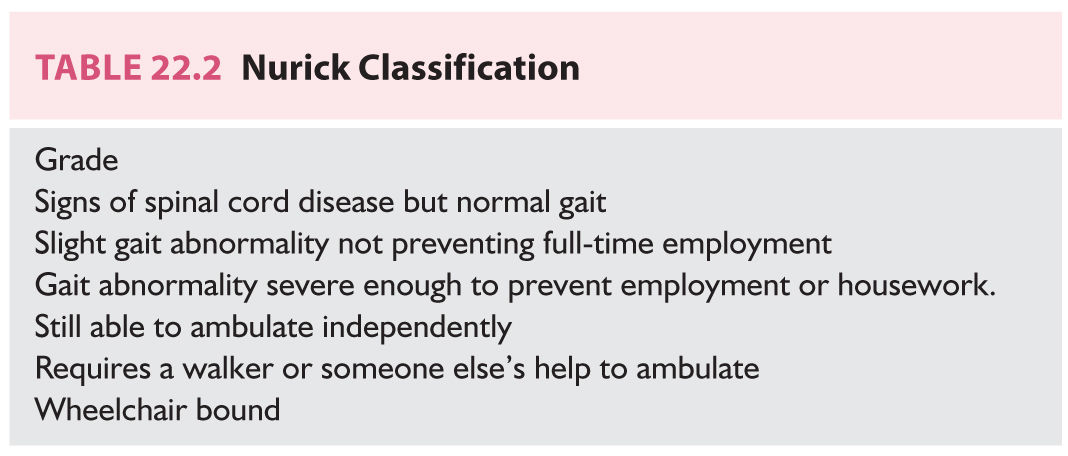

b. MRI scan (Fig. 22.2). MRI is excellent for demonstrating nerve-root compression and spinal cord compression from bone spurs. It does not provide as much detail about bone anatomy as the CT scan.

c. CT scan. CT shows better bone detail than does MRI but is not as good at showing the neural structures. The two studies together are ideal for this group of patients, but this is obviously not cost-effective, so MRI is the first choice.

4. EMG and NCS studies. The EMG can be helpful in discerning which roots are most involved in patients with multilevel spondylosis.

D. Referral.

1. Medication. As discussed in previous medication sections.

2. Soft cervical collar.

3. Physical therapy. Heat, ultrasound, massage, traction, and TENS can reduce the symptoms. Approximately 20% of the radiculopathies (arm pain/strength) can be successfully improved with medicine and therapy alone for many years. The majority of patients have some pain with persistent mild weakness (if any weakness is present). Rarely does myelopathy develop in this group of patients.

FIGURE 22.2 Sagittal MRI of cervical spondylosis demonstrating multiple level involvement.

4. Spine specialist. Surgery for cervical spondylotic radiculopathy is almost always elective. Results of surgery are much better for single-level disease than for multilevel disease—especially for neck pain. Arm strength of 3/5 or worse and any evidence for myelopathy are indications for immediate referral to a spine surgeon. The anterior approach is superior to the posterior approach if bone spurs project under the entire spinal cord. Surgery helps the radiculopathy in 90% to 95% of both single-level and multilevel disease patients, but neck pain improves in only 70% to 75% of multilevel disease patients. Complete relief of radicular pain occurs in approximately 60% to 80%. There is no age cutoff for surgery as long as patient is in reasonable medical condition. The elderly tolerate surgery very well with minimal morbidity. If a myelopathy is present with gait abnormality and an aggressive decompression is performed, an improvement of one grade on the Nurick scale (see Table 22.2) can be expected in 70% to 80% of patients. Duration of symptoms is very important for patients with gait problems. Thus, early referral is indicated.

NECK PAIN WITH/WITHOUT ARM PAIN DUE TO METASTATIC CANCER OF THE CERVICAL SPINE

A. Introduction. As patients live longer with various malignancies, the number of patients who present with spine metastases also increases. The tumors that most commonly involve the spine are lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, lymphomas, and multiple myelomas. As many as 20% of these tumors will develop symptomatic spinal involvement. In approximately 10% of patients, metastatic spinal involvement will be the mode of presentation with no known primary tumor.

B. Evaluation

1. History and physical examination. Both primary and metastatic tumors of the spine initially present with pain that is often worse at night. The pain continues to worsen over a very short period, and then neurologic symptoms such as radiculopathy and myelopathy develop fairly quickly. It is best to make the diagnosis when neurologic symptoms are minimal.

2. Radiographs.

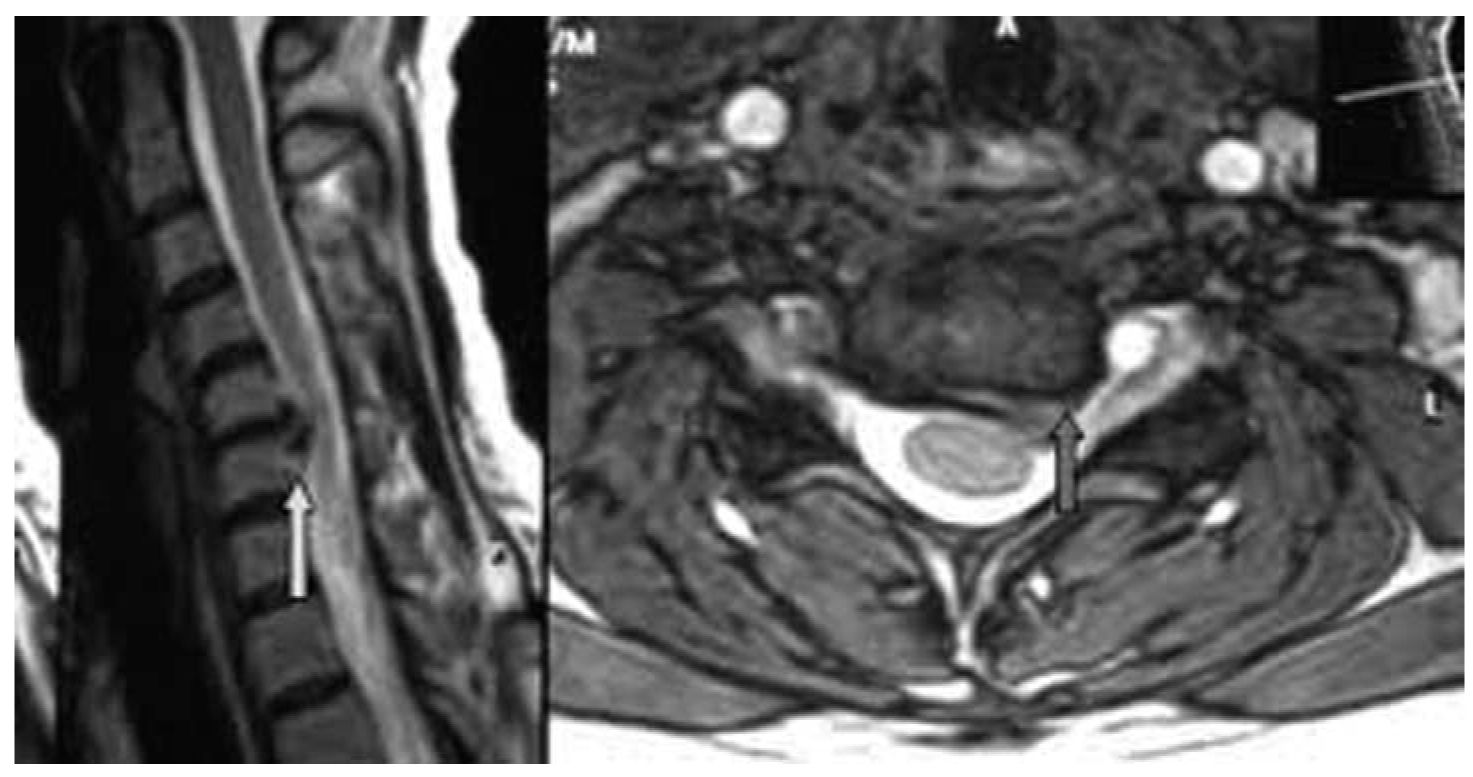

a. Plain X-rays can show destruction of the vertebral bodies and pedicles (Fig. 22.3). Pathologic compression fractures and lytic pedicles are very common. The sensitivity of plain X-rays is approximately 60%.

b. Bone scans are very sensitive—approaching 100%—in showing spine metastases, including asymptomatic areas with no destruction.

c. MRI scans are ideal for delineating canal involvement, cord compression, and surgical feasibility.

C. Referral.

1. Radiation therapy. Diffuse disease involving large amounts of the spine is treated primarily with steroids and radiation therapy. Radiation is usually reserved for the symptomatic areas only. Dexamethasone 2 to 20 mg PO q6h can be quite helpful in improving pain and neurologic symptoms.

2. Surgery. Early referral to a spine surgeon is warranted following diagnosis regardless of the neurologic examination. If surgery is indicated, it is often best to perform it prior to radiation therapy, because this reduces the wound complication rate. In the face of a cervical myelopathy resulting from diffuse canal involvement and cord compression, a laminectomy can be performed. Patients with lung cancer do very poorly, and it is hard to justify surgery scientifically for metastatic lung cancer unless there is no primary disease and the spine disease is the only systemic metastasis. Other tumors do better, but a good rule is 30% to 50% of all tumors are improved by laminectomy with a 10% mortality rate. Isolated vertebral body disease can be resected from an anterior approach—especially in well-controlled breast cancer, prostate cancer, lymphoma, and renal cell cancer with excellent long-term results that are superior to radiation alone.

MISCELLANEOUS NECK PAIN WITH/WITHOUT ARM PAIN

A. Rheumatoid arthritis.

1. Etiology. Rheumatoid arthritis can affect the C1–C2 articulation leading to erosion of the odontoid process and transverse atlantal ligament, which leads to C1–C2 instability, and cord compression from the developing panus.

2. Evaluation

a. History and physical examination. Severe neck pain is usually followed by arm pain and a progressive myelopathy.

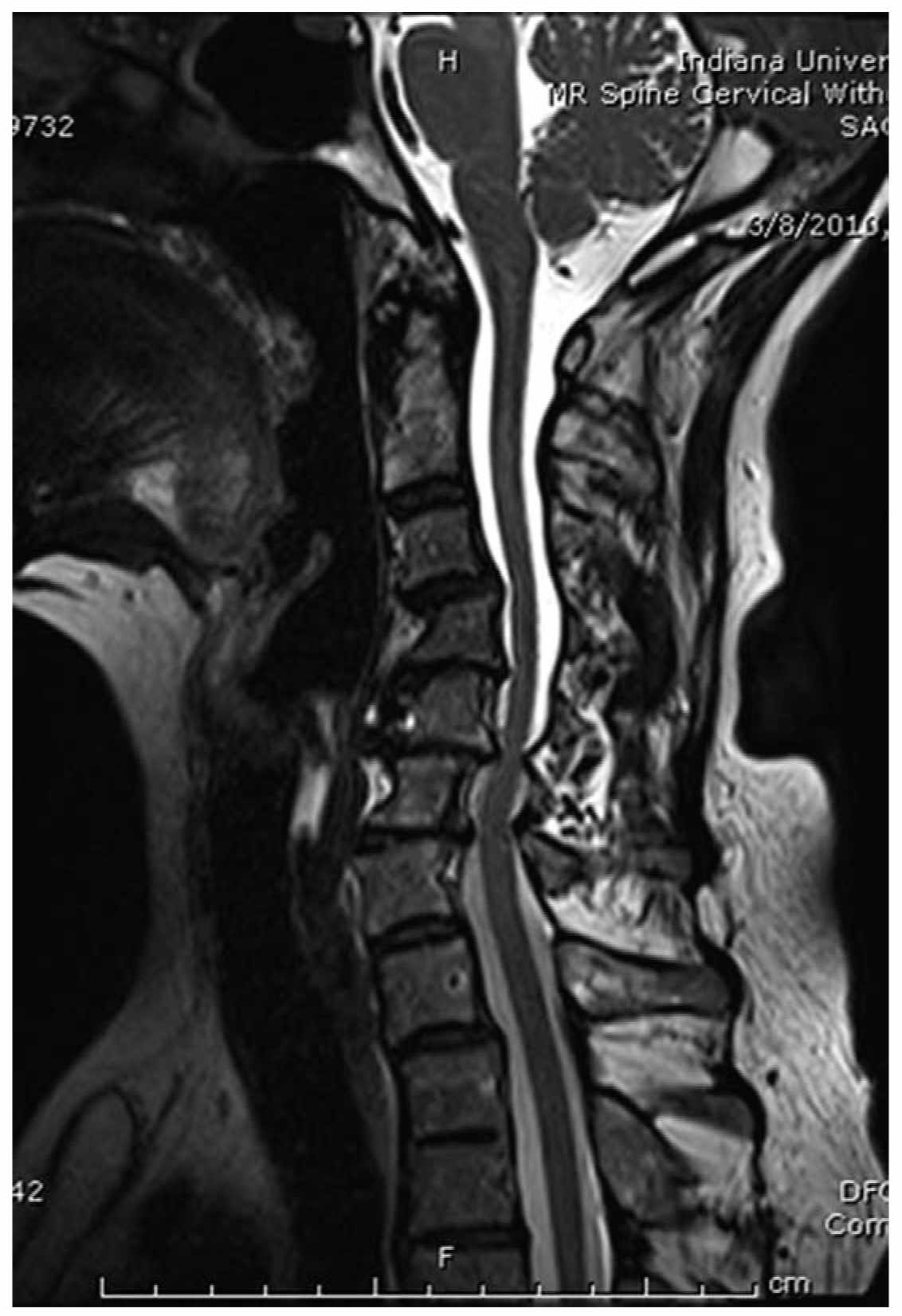

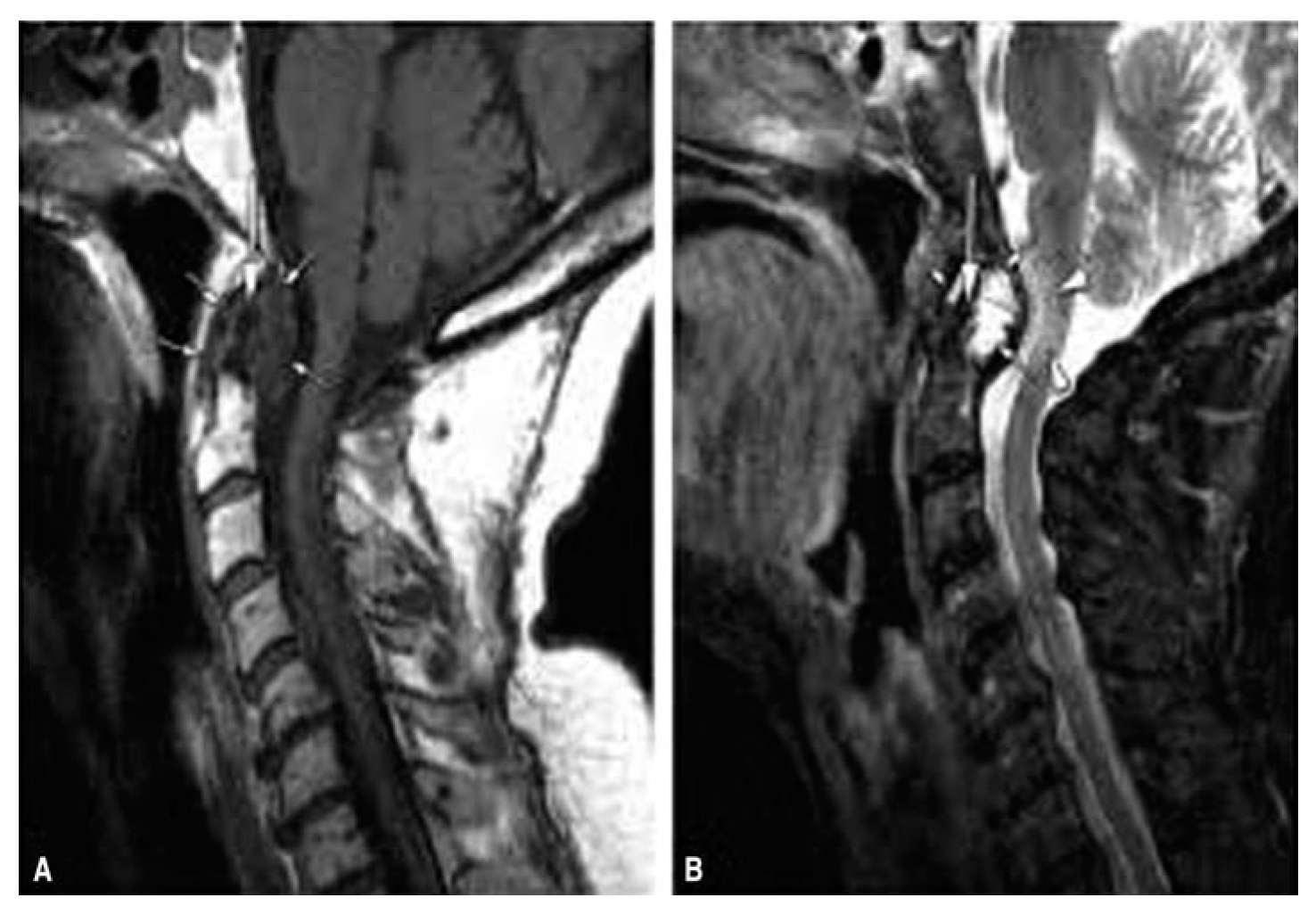

b. Radiographs. Plain X-rays and MRI scans are best for showing erosion of the odontoid process with subsequent instability and spinal cord compression (Fig. 22.4).

3. Referral and therapy. Place a soft collar and refer immediately to a spine surgeon. Posterior C1–C2 fusion with transarticular screws is ideal for the problem; occasionally an anterior transoral odontoidectomy is required. These treatments are not without risk and must be individualized.

B. Discitis/osteomyelitis.

1. Introduction. Bacterial discitis/osteomyelitis is extremely uncommon in the cervical spine and fever may not be present.

FIGURE 22.3 Lateral radiograph demonstrating lytic destruction of cervical vertebral bodies by tumor.

2. Evaluation.

a. History and physical examination. There may be a prior history of skin infection, urinary tract infection, or pulmonary infection. Iatrogenic diskitis/osteomyelitis complicating cervical spine surgery is known to occur. Perhaps the most common cause in urban settings is a history of intravenous (IV) drug abuse. Progressive neck pain with a rapidly progressive myelopathy is the usual presentation.

b. Radiographs. Plain X-rays show disk space collapse with erosion of the bordering vertebral bodies. MRI shows epidural spinal cord compression from kyphosis or epidural abscess.

3. Referral. The patient should be immediately referred to either a spine specialist or an infectious disease specialist. An immediate radiology-directed needle biopsy/culture or open biopsy culture, and administration of IV bactericidal antibiotics for at least 6 weeks, are indicated.

Surgical debridement and decompression are performed for severe kyphosis and neurologic problems.

FIGURE 22.4 A and B: Sagittal MRI scans in rheumatoid arthritis demonstrating destruction of the dens with compression of the medulla and spinal cord at the craniocervical junction.

Key Points

• Nonoperative management of neck pain.

• Neurologic findings of cervical radiculopathy due to cervical disc herniation or cervical spondylosis and treatments.

• Miscellaneous causes of neck pain with/without arm pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree