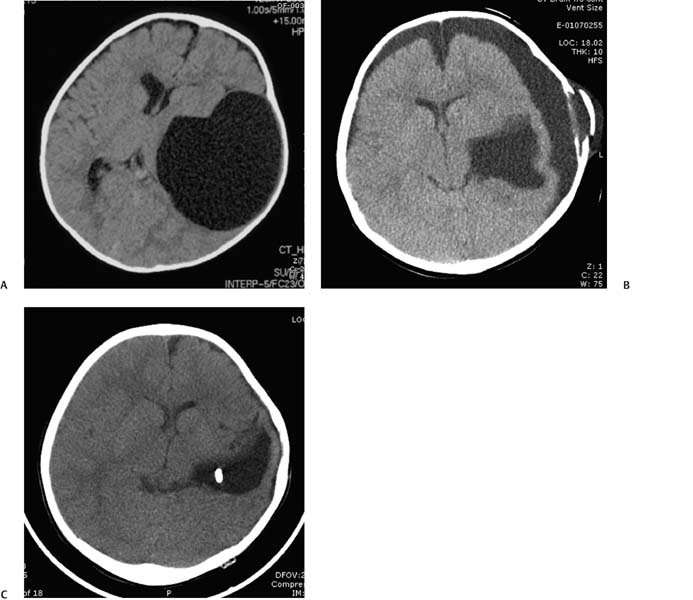

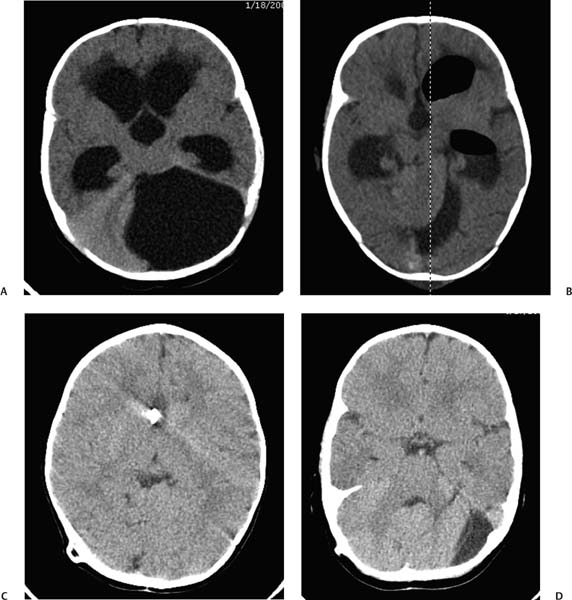

1 Arachnoid Cysts Arachnoid cysts are developmental anomalies occurring between layers of the arachnoid membrane that are frequently encountered in pediatric patients. Often they are discovered incidentally and remain clinically silent. In a minority of cases, however, arachnoid cysts can cause symptoms via mass effect on surrounding structures, spontaneous rupture or hemorrhage, or obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) outflow pathways. They have been associated with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations in pediatric patients, including headaches, macrocephaly, hydrocephalus, seizures, and motor/developmental delays.1–6 Patient evaluation is a key factor in the management of arachnoid cysts, as a majority of these lesions can be managed conservatively with sequential imaging. In the past, the optimal initial management of symptomatic arachnoid cysts requiring surgical intervention has been debated. Although several options for treating arachnoid cysts have been used in the past, by far the two most frequently used modalities have been CSF shunting procedures, such as cystoperitoneal shunting, and craniotomy with fenestration of the cyst membrane.5 Either shunting or fenestration can be employed as a primary procedure, and each approach carries with it its own set of risks and benefits. Both procedures clearly have a useful role in the management of arachnoid cysts, and the optimal management of pediatric patients is likely more contingent on knowing when to use the correct procedure. Fenestration offers the clear benefit of potentially rendering patients shunt independent for life, yet it is unsuccessful in a certain proportion of cases. Cystoperitoneal shunting is usually relied on as a definitive backup measure when fenestration is unsuccessful or as a primary treatment for arachnoid cysts when there is clear evidence of coexisting hydrocephalus. Shunt procedures have been used as a treatment for arachnoid cysts for decades. Although cystoperitoneal shunts remain the most commonly performed diversion procedure for treating arachnoid cysts, other shunt procedures, such as ventriculoperitoneal, cystoventriculoperitoneal, cystocisternal, and cystoventricular shunts, have been used by some surgeons.7–9 CSF fluid shunting procedures offer several advantages over open craniotomy with fenestration for the treatment of arachnoid cysts. Foremost, the overall success rate of cystoperitoneal shunt procedures in decreasing the size of arachnoid cysts and reducing mass effect on surrounding structures is higher than in major reported series of craniotomy and fenestration.1,4,10,11 Nevertheless, fenestration procedures are frequently attempted by many centers because a major emphasis is placed on shunt avoidance, if possible. It has been theorized that cystoperitoneal shunts address the underlying problem relating to arachnoid cysts and a potential underlying mechanism for their expansion, namely impaired CSF flow dynamics. Furthermore, shunt procedures are frequently required following attempted craniotomy with fenestration, whether in the form of a cystoperitoneal shunt, ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or subdural-peritoneal shunt3,12 (Fig. 1.1). The rate of shunt dependence following craniotomy with fenestration has been reported as 43 to 80% in larger series.2,9,10,13 A study by Ciricillo et al reported that 12 of 15 children (80%) treated initially with fenestration were shunt dependent following surgery.10 A previous study from our institution reported an overall postfenestration shunt dependence rate of 55%.9 Fig. 1.1 (A) Preoperative non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating a large left middle fossa arachnoid cyst. (B) Initial follow-up CT scan showing a decrease in the cyst size and the development of subdural hygromas. (C) Follow-up CT scan obtained after placement of a cystoperitoneal shunt revealing improvements in the cyst size and hygromas. The requirement for shunting following fenestration depends significantly on the presence or absence of hydro-cephalus.2,9,13 Most authors are in agreement that patients with hydrocephalus and an arachnoid cyst will require a shunt procedure1,2,9,10,13,14 (Fig. 1.2). Along the same lines, infants with arachnoid cysts presenting with macrocephaly, without underlying hydrocephalus, are also significantly more likely to be shunt dependent following a fenestration procedure.13 A more recent study from our institution assessed the rate of postcraniotomy shunt dependence for patients younger than 2 years of age with arachnoid cysts, when grouped by clinical presentation. The proportion of postfenestration shunt dependency according to patients’ clinical presentation was 83% in patients with hydrocephalus, 57% in patients with macrocephaly, and 7% in patients presenting with all other symptoms (p=.0039, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test).13 These findings suggest that patients presenting with arachnoid cysts and macrocephaly without ventriculomegaly (in addition to patients with hydro-cephalus) have an underlying aberrancy with CSF flow and absorption, perhaps resulting in a forme fruste state of hydrocephalus. Of note, some authors have reported that an even more influential factor than the type of surgical intervention used in determining the success rate of treatment is the location of the cyst.10,15 Some surgeons have indicated that a major goal in the treatment of arachnoid cysts is establishing equilibration of intracystal pressure with intraventricular pressure. For this reason, some reports have stated that cystoperitoneal shunts do not adequately restore physiologic intracranial pressure but instead result in overdrainage of the cyst compartment.16 This dynamic, of course, depends in part on the valve system that is employed in the cystoperitoneal shunt system. One concern that has been raised with the use of shunt systems is rapid overdrainage of arachnoid cysts, potentially resulting in extra-axial hematomas.17,18 Similarly, many authors have reported that complete obliteration of a cyst is not required to achieve improvement in patients’ symptoms, but that a small decrease in cyst size is usually sufficient in doing so.8 In recent years, programmable shunt valves have been increasingly used with excellent surgical results, potentially due to the regulated, gradual reduction offered by these systems.17,19–21 Some authors have advocated cystoventriculoperitoneal diversion procedures in an effort to equilibrate the intracystal and intraventricular pressures.4,14 Others have been less supportive of this technique, given the more complex Y-shaped connection requirement and the need for additional catheter insertion.2,8 In an effort to restore the communication between all intracranial CSF spaces, some surgeons have advocated the use of cystoventricular shunt systems with acceptable surgical results in patients without hydrocephalus.7,8 Fig. 1.2 (A) Initial non-contrast-enhanced CT scan exhibiting a posterior fossa cyst and hydrocephalus. (B) Postoperative CT scan obtained after fenestration showing improvement in the cyst size as well as ventriculomegaly. (C,D) Follow-up CT scans revealing the patient’s status following placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. In addition to often being the more definitive procedure for the management of arachnoid cysts, cystoperitoneal shunt procedures are associated with a relatively low risk profile.4,10,22–24 The risks of cystoperitoneal shunt insertion or revision are generally reported as being lower than for craniotomy with fenestration.4,10,11,25 Shunt insertion for arachnoid cysts is generally a less invasive procedure than craniotomy with fenestration, although endoscopic fenestration and the use of adjunct neuronavigation have certainly provided minimally invasive fenestration of cysts in recent years.15,26,27 Open craniotomy for cyst fenestration has been associated with a higher risk profile and has been reported to cause postoperative complications, including hemiparesis, cranial nerve palsies, hypothalamic injury, increased seizure frequency, and postoperative hematomas.2,3,10,12,28,29 Shunt procedures, however, carry with them the lifelong burden of shunt dependence and associated potential risks, such as infection, malfunction, and overdrainage.1,4,10,23 The rate of subsequent revision for cystoperitoneal or associated shunts has been reported as 10 to 50%.1,2,4,9–11 Undoubtedly, a minority of patients will require multiple shunt revisions. In one large series of 77 patients treated with cystoperitoneal shunts, 8 patients (10%) experienced a total of 12 shunt malfunctions over a mean follow-up time of 7.7 years.1 The mean time to shunt malfunction following shunt operation was 4.8 years. It has been noted that successful cystoperitoneal shunting can lead to opposition and eventual scarring of the arachnoid membranes, resulting in obliteration of the cyst.1,10 In these cases, subsequent shunt malfunction may not result in reexpansion of the cyst or recurrence of symptoms. Arai et al noted that the degree of long-term shunt dependency was related to the size of the cyst, with larger cysts being more likely to present with shunt malfunction and intracranial hypertension.1 Furthermore, they reported successful removal of cystoperitoneal shunts without cyst recurrence in 12 cases, with a mean follow-up time of 3.3 years. In conclusion, patients with symptomatic arachnoid cysts can be treated with a variety of surgical interventions. Each patient must be assessed on an individual basis in regard to the requirement for surgery and the optimal first-line intervention. Key factors in this decision-making process include the location and size of the cyst, the proximity to adjacent cisternal spaces, and the presence or absence of hydro-cephalus. Cystoperitoneal shunting is a relatively low-risk and effective method of treating arachnoid cysts, especially in cases of unsuccessful fenestration and in patients with hydrocephalus. Given the major emphasis placed on shunt avoidance at our institution, fenestration remains a preferred primary treatment in patients with symptomatic cysts, especially in those without hydrocephalus and macro-cephaly. Nevertheless, cystoperitoneal shunting remains a useful, often definitive procedure in the management of pediatric arachnoid cysts. Arachnoid cysts are the most common nontraumatic intracranial lesions, with a reported frequency as high as 1 in 1000. First recognized in 1831, they can present with headaches, seizures, accelerated head growth, or associated hydrocephalus; however, given the relatively higher frequency in autopsy studies, most are asymptomatic.30 As such, the natural history of arachnoid cysts is poorly understood, with reports in the literature of both spontaneous resolution and progressive enlargement.31–33 Furthermore, the pathophysiology of arachnoid cysts is not well understood. Most theories center on a gradual accumulation of CSF into a congenitally abnormal compartment via a “ball-valve” effect. Oftentimes, areas thought to be arachnoid cysts may in actuality be regions of periventricular encephalomalacia following perinatal infarction and may respond to standard CSF diversion (i.e., ventriculoperitoneal shunting or endoscopic third ventriculostomy). Alternatively, loculated fluid collections resulting from intraventricular adhesions, more common in children with hydrocephalus due to intraventricular hemorrhage of prematurity or meningitis, may also occur. This discussion will center on arachnoid cysts believed to be congenital; however, many of the same surgical principles may be extrapolated for secondary pathology.

Cystoperitoneal Shunting

Benefits of Cystoperitoneal Shunt Procedures

Risks of Cystoperitoneal Shunt Procedures

Open or Endoscopic Fenestration

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree