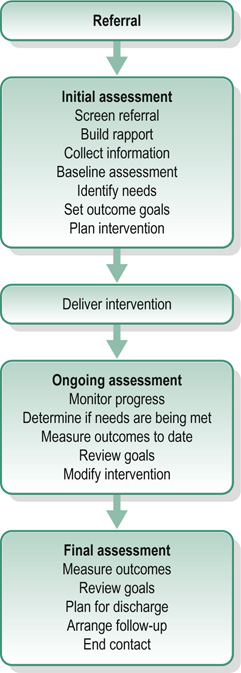

5 CHAPTER CONTENTS ASSESSMENT AND OUTCOME MEASUREMENT PROCESS Stage 2: Ongoing Assessment and Evaluation Stage 3: Final Assessment (and Outcome Review) Abilities, Strengths and Interests Individualized Outcome Measures Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) Patient-Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) Clinician-Reported/Rated Outcome Measures (CLOMs also ClinROs) Assessment and outcome measurement are integral parts of the occupational therapy process and commence at the point of referral. (It may be helpful to read this chapter in tandem with the description of the occupational therapy process in Ch. 4.) The occupational therapy process begins with the end in mind (Covey 1989), by thinking about the outcome at the beginning of the process. This means it is clear from the outset what the end-point of therapy is. It also makes it possible to make a judgement about whether the outcome has been achieved and to identify if there has been a change in the person’s situation. Assessment is measurement of the quality or degree of the various factors in a situation or condition. For occupational therapists in clinical practice, assessment is used to measure the strengths and needs of the person that relate to their referral for occupational therapy. Outcome measurement involves comparing a person’s level of function after intervention with what they were able to do before. Outcomes are the expected or intended results of intervention. The desired outcome is the goal that the individual and therapist want to achieve in their work together. The actual outcome is the measurable result of the intervention. Outcome measurement is the evaluation of the extent to which an outcome goal has been reached (Creek 2003), consequently outcome measures are measures of change over time, therefore before beginning intervention, it is necessary to establish the individual’s current level of functioning. This chapter will discuss the part that assessment and outcome measurement play in the occupational therapy process including the importance of reliability and validity. It will also consider what is assessed, methods of assessment and different approaches to measuring outcomes. The assessment and outcome measurement process, as shown in Figure 5-1, is an integral part of the occupational therapy process. Assessment and outcome measurement is not something that is ‘done to’ a person. Outcomes are identified collaboratively by the individual and the therapist. Together, they are actively involved in providing information and in interpreting it; they are involved in determining the goals to be attained and expressing them in such a way that they are measurable. During the process of assessment, the therapist’s focus of attention shifts between different aspects of the person’s performance; skills, tasks, activities and occupations (Creek 2003). There may be long-term outcomes or shorter term, i.e. specific, measurable and realistically achievable steps towards meeting an agreed longer-term goal. These steps should be in a form that is readily understood by the individual involved, the therapist and any others involved. The emphasis is on strengths, promoting engagement and goal achievement. Assessment and outcome measurement takes place in three stages; initial assessment; ongoing assessment and evaluation; and final assessment FIGURE 5-1 The assessment and outcome measurement process. Initial assessment takes place at the start of the occupational therapy process and can be described as a way of defining the problem to be tackled or identifying the goal to be achieved. It involves collecting and organizing information about the person from a variety of sources in order to identify the challenges they are experiencing, set goals for the outcome and plan interventions effectively. The steps of the initial assessment process described here may not be carried out in the same sequence with every person. The assessment process is shaped by the individual needs and wishes, the context of the intervention, and other constraints. Initial assessments can also be useful for judging whether or not the person will benefit from occupational therapy intervention and rapport building. This is an example of the art and skill of occupational therapy. An occupational therapist may be administering a test but the manner in which they do it will convey their values (respect, empathy, trustworthiness and partnership working) to the person they are working with. This not only supports the assessment process but provides a solid foundation for intervention. No one part of the occupational therapy process is unrelated from the other. Occupational therapy intervention can only begin when assessment clearly indicates the need for it. The outcome of an initial assessment may be a decision not to provide an occupational therapy intervention. An example of this would be a person whose alcohol use is directly affecting their occupational performance who needs to acknowledge the problem to benefit from intervention. Recording the results of investigations is the starting point for interpretation and, as such, is part of intervention planning. The process of organizing information, which should be carried out as far as possible with the active cooperation of the person concerned to produce a list of problems and strengths, agree on goals of intervention and suggest strategies and methods of intervention. These last two aspects of the occupational therapy process are discussed in detail in Ch. 6, which focuses on planning and implementing interventions. To monitor change and progress, assessment and evaluation are ongoing. This enables the therapist, working collaboratively to determine if person’s needs are being met, obtain further specific information, modify interventions or review planned outcomes. The frequency of these assessments will depend on the type of service and expected length of the intervention. Reviews can include: ■ Once an intervention has been implemented, the therapist again assesses an individual’s skills, the effect on tasks and activities and, finally, whether this means that the individual is now better able to perform their usual range of occupations (or desired occupations) ■ Ongoing review, which may involve activities such as: observation and discussion; regular completion of tools such as diaries or Likert scales; and repetition of previous standardized or non-standardized assessments. This takes place at the end of the intervention. It can be used to: ■ provide a picture of residual problems ■ plan for appropriate discharge and follow-up ■ identify reasons why no further progress can be made at this time. It is not possible, or necessary, to learn everything there is to know about a person. An occupational therapist collects and organizes information about the person, working within the context of the referral, the nature of the service offered and the frame of reference being used by the therapist. This section will focus on the occupational therapist’s domains of concern; namely occupations, routines and habits, abilities, strengths and interests, roles, volition and motivation, aspirations and expectations, areas of dysfunction, external factors and risk. It is useful to take an occupational history. This is to assess whether the individual’s roles and occupations have been disrupted or whether they have developed supportive and helpful habits and routines. Occupations are enacted through activities; for example, the occupation of mothering is expressed through such activities as bathing her child, feeding her child, playing with her child, reading to her child and answering her child’s questions. The therapist will seek to discover what activities the individual normally performs and whether or not these activities support a healthy range of occupations, and equally whether they are supportive of roles that enable the person to feel like they fit or belong in the wider context/world around them. Occupations exist in a balance that changes throughout the life cycle. A healthy balance is one that allows most of the individual’s needs to be satisfied in ways that promote social inclusion and integration. This balance can be disrupted by illness or disability but, equally, an inability to participate in a range of chosen occupations can have a negative impact on health (Creek 2003). The therapist assesses how a person uses their time over the course of days and weeks, whether there are empty times or times when there is too much to do. It is also helpful to find out if the person’s time use has changed recently, perhaps with the loss of a major occupation or with the introduction of new demands? Daily activities are organized into routines that support an individual’s sense of self and, if performed regularly, become habitual; for example, driving involves a sequence of actions that becomes habitual so that one does not have to think carefully about every stage of the operation. Routines and habits enable the individual to perform everyday tasks without having to remember consciously how to go about them. They are developed to suit the individual’s needs at any one period of life; new habits are learned and old ones discarded as circumstances change. The therapist assesses how people organize their time; that is, whether they have useful habits or have to expend a lot of time and energy deciding what to do and working out ways of performing. Abilities, strengths and interests also influence the range of occupations a person adopts and the way these occupations are performed. Ability is the measure of the level of competence with which a skill is performed. In order to function effectively in a desired range of actions, a person must have a variety of skills and be able to perform them competently. When assessing individuals, it should be taken into account that competence is not an absolute concept; norms for competence vary with age and are to some extent socially defined (Mocellin 1988). Competence exists on a continuum and when assessing competence in completion of skills, it is important for the therapist to acknowledge their own bias and thresholds for acceptability and to question these in the context of the individual they are working with. Strengths are the personal factors that enable a person to function effectively. They include skills, other personal attributes and social networks. The therapist assesses an individual’s strengths, so that interventions can be designed to support and build on them as an enabler of change. Interest is the expectation of pleasure in an activity which is aroused by a combination of experience and some degree of novelty. Experience tells us that we have enjoyed something similar in the past and novelty arouses in us the urge to try a new experience. It is important to know what an individual’s interests are so that interventions can be designed that are appropriate and support an individual’s sense of self. Gaining understanding of an individual’s occupational choices and whether these are externally or internally influenced helps to ascertain whether interests are genuine or presumed. For example a person may spend a lot of time watching shopping programmes on television, but it would be wrong to presume this is due to interest; it may be due to an inability to sleep. Roles are patterns of activity associated with social position. A role contributes to the individual’s sense of social and personal identity and also influences the way in which occupations are performed. A properly integrated role, supported by the skills and habits necessary for its performance, satisfies both society’s expectations and the individual’s needs. Roles are defined by society and assigned to individuals on the basis of such attributes as age, gender, relationships, possessions, education, job, income and appearance. For example, a person’s roles vary in different places: their role at work; being a consumer when shopping and being a parent at home. Each role carries expectations of occupational performance, which the individual who accepts the role attempts to carry out. Therefore, an occupational therapist should consider roles as part of assessment. The range of roles and occupations the person has engaged in over time should be explored, as well as the level of satisfaction these have provided for them, and what barriers or restrictions to role participation the person has previously experienced. People have a basic urge to be active, known as volition. They test their own potential and seek to have an impact on their surroundings. The extent to which they act on that urge is known as motivation. The actions they choose are influenced by life experiences. Fidler and Fidler (1978) stated that each person learns their own capacities through doing. Assessment should include exploration of an individual’s occupational behaviour and their ability to choose what to do and initiate it. Decisions about what to do may be influenced by the person’s internal beliefs, values and interests, but also by their level of competence and external environments and relationships. Developing an understanding of these during the assessment will help the therapist influence change during the intervention phase. Achievement through participation is influenced by an individual’s aspirations and expectations. A person who has experienced persistent failure, due to a lack of skill or lack of opportunity to do, may feel incompetent, lacking in control and have little expectation of success or hope for the future. This will influence how a person engages and what in. Successful doing leads to a sense of satisfaction and a sense of competence and therefore builds confidence and aspirations. It is important that interventions match the person’s aspirations and expectations, offering a ‘just right challenge’. However, the capacity to make realistic plans for the future can be affected by fear of failure or by illness. The assessment process is designed to elicit both what the person would like to achieve and how realistic those aspirations are. Function and dysfunction are not opposites but exist on a continuum. Spencer (1988, p. 437) pointed out that: Temporary or permanent disability takes on a unique meaning for each individual. Age, developmental stage, previous ability, achievements, life-style, family status, self-concept, interests and general responsibilities affect attitudes such as understanding, acceptance, motivation and emotional response …. An accurate analysis of the bio psychosocial context by the therapist is essential to determine the functional implications of the patient’s condition.

Assessment and Outcome Measurement

INTRODUCTION

ASSESSMENT AND OUTCOME MEASUREMENT PROCESS

Stage 1: Initial Assessment

Stage 2: Ongoing Assessment and Evaluation

Stage 3: Final Assessment (and Outcome Review)

WHAT IS ASSESSED?

Occupations

Routines and Habits

Abilities, Strengths and Interests

Roles

Volition and Motivation

Aspirations and Expectations

Areas of Dysfunction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree