CHAPTER 116 Basic Principles of Skull Base Surgery

Historical Landmarks

Until the beginning of the 20th century, lesions located at the base of the skull were largely inoperable. Pioneers of different surgical areas started to envision and perform many of the significant approaches to the skull at the end of 19th century, and success was achieved in single cases. Classic examples are the suboccipital approach by Krause,1 transsphenoidal approaches to pituitary tumors introduced by Halstead,2 and the translabyrinthine route described by Panse.3 These techniques were then improved and became part of the routine armamentarium of the next generation of surgeons, including Cushing, Dandy, Guiot, Dott, Wüllstein, and Conley, among others.4 However, it was not until the mid-1960s that efforts to overcome interdisciplinary barriers led to further breakthroughs in skull base surgery and close cooperation among neurosurgeons, otorhinolaryngologists, and maxillofacial surgeons. The introduction of microsurgical techniques, advances in neuroanesthesiology, and new diagnostic tools such as high-resolution computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and superselective angiography were also essential.

Overview of Skull Base Surgery

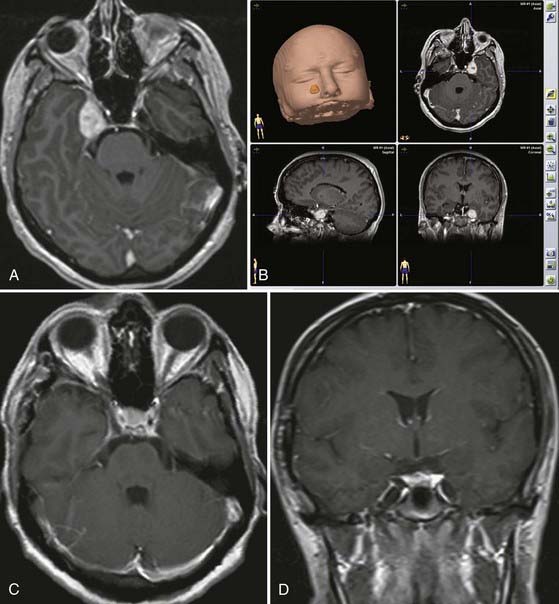

The second goal of skull base surgery involves the principle of drilling the skull base while avoiding major trauma to the brain. Experience with surgery on the skull base has shown the benefits of bone resection in reducing the need for brain retraction. Its indications have been expanded over the years to treat not only skull base–destroying lesions but also all intracranial lesions that can best be reached through the skull base. For example, some aneurysms of the basilar artery, although not true skull base lesions, are better attacked through transzygomatic or transpetrosal approaches, which involve minimal brain retraction and afford an enhanced view. High-speed drill techniques developed rapidly, and the drill has become a precise microsurgical instrument. Based on these principles, several approaches through the skull base were established, such as transfacial approaches, transpetrosal approaches, transcondylar approaches, and many others. The main goal of these techniques is to reduce the amount of brain retraction by means of bone resection, thus avoiding problems related to postoperative brain contusion and edema. Furthermore, the approach in itself should not be associated with significant procedure-related morbidity. Developments in computer technology and navigation devices have allowed online control of bony structures during the drilling procedure and tumor resection.5–9 Moreover, navigation may be used for localizing displaced or encased vessels, as well as for assessing tumor extension and its relationship to main landmarks (Fig. 116-1).

![]() Over the past decade the endoscope has become a widespread supplement to traditional skull base techniques, whether used in addition to the microscope or as the only visualizing tool.10–12 It provides a panoramic multi-angled view of the entire operative field. Freehand use of the endoscope allows a close-up view of the target area, and angled endoscopes enable one to see “around the corner“ (Video 116-1).

Over the past decade the endoscope has become a widespread supplement to traditional skull base techniques, whether used in addition to the microscope or as the only visualizing tool.10–12 It provides a panoramic multi-angled view of the entire operative field. Freehand use of the endoscope allows a close-up view of the target area, and angled endoscopes enable one to see “around the corner“ (Video 116-1).

Trigeminal schwannoma—endoscopically assisted retrosigmoid suprameatal approach.

The retrosigmoid suprameatal approach was selected.

The schwannoma is initially debulked and dissected from the neural branches.

Complete tumor removal is accomplished. The uninvolved trigeminal branches are preserved.

Our years of experience in treating skull base lesions have allowed us to recognize a number of cases in which the use of extensive skull base procedures does not improve the surgical result and may in fact endanger it. In particular cases, extensive skull base approaches may significantly increase the risk for postoperative deficits. We are now past the era of enthusiastic resection of skull base lesions, and simple cranial approaches are again gaining popularity. Thus, some simple approaches, such as the retrosigmoid approach to the cerebellopontine angle, have proved to be most favorable for tumors in that location. In other cases, however, the approach has to be selected individually and always tailored to the characteristics of the particular tumor, its location, and the patient’s expectations.13

Surgery on the Anterior Skull Base

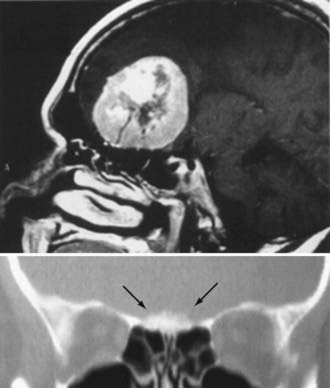

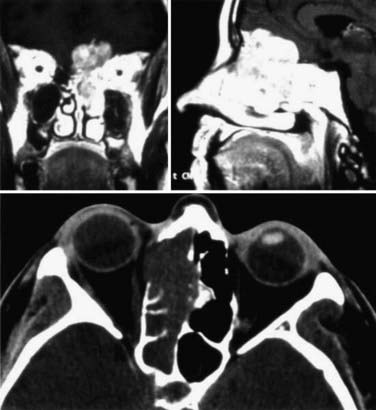

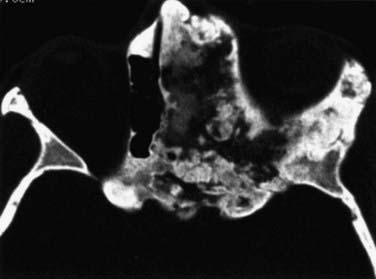

Different lesions may involve the anterior skull base, such as benign or malignant tumors, vascular lesions, maldevelopmental diseases, and trauma. Meningiomas of the olfactory groove and planum sphenoidale are the most frequent benign tumors encountered at the anterior skull base (Fig. 116-2).4,14 Adenocarcinomas and esthesioneuroblastomas are typical examples of malignant tumors that arise from the paranasal sinuses and secondarily involve the anterior skull base (Fig. 116-3). Fibrous dysplasia develops very slowly but may achieve a large size before it becomes symptomatic (Fig. 116-4). Other non-neoplastic lesions of the anterior cranial base include frontal encephaloceles and skull base trauma. Each of these lesions needs a particular treatment strategy. The surgeon must be familiar with the normal surgical anatomy of the skull base to understand the changes caused by these lesions and to manage them properly.

FIGURE 116-4 Fibrous dysplasia with extensive involvement of the anterior skull base on the left side.

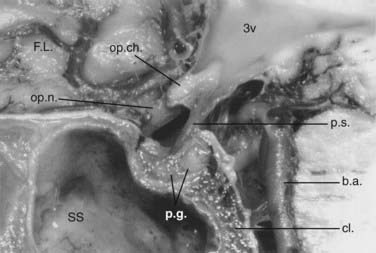

Operative Anatomy of the Anterior Skull Base

From the endocranial view, the anterior cranial base has a flat surface that comprises the anterior border of the sphenoid wings and the roof of the orbita laterally and the planum sphenoidale medially (Fig. 116-5). In the middle, in varying prominence and height are the crista galli and the ethmoid plate. The dura in the medial portion at the area of the cribriform plate is more closely adherent to the skull base than in the lateral position. Depending on the degree of pneumatization of the paranasal sinuses, the size of the contact area between the paranasal sinuses and the anterior skull base may vary.15,16

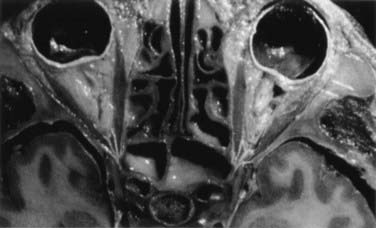

The ethmoid cells form the lateral boundary of the contents of the orbita at the level of the skull base (Fig. 116-6). Medially, the lamina cribrosa constitutes the upper limit of the paranasal sinuses, and it is divided by the nasal septum. Behind are the two portions of the sphenoidal sinus. These portions vary in size, as do the other paranasal sinuses. Figure 116-7 shows the relationship of the sphenoidal sinus to the sella and its contents, along with the surrounding structures.

FIGURE 116-6 Axial section through the anterior skull base at the level of the orbits and ethmoidal sinus.

Extracranial Approach to the Anterior Skull Base

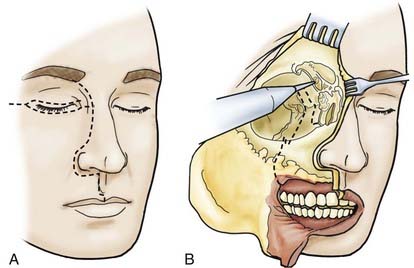

Extracranial Approach with Unilateral Orbital Exenteration

The skin incision is extended, in accordance with extension of the tumor, paranasally toward the upper lip. If necessary, the lip is split (Fig. 116-8). The stepped incision produces a favorable aesthetic result. With ethmoidal tumors, depending on the extent of involvement of the medial edge and orbit, a decision must be made whether the upper and lower lids have to be resected or only the skin near the edge needs to be sacrificed. In the latter case, the upper and lower lids can be used as tissue for epithelialization of the remaining orbita. The extent of freeing the soft cheek tissues is determined by the extension of the tumor.

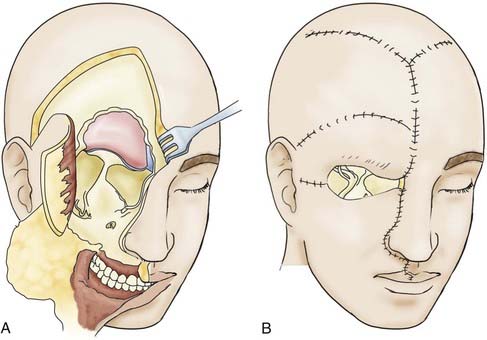

To guard against infection, the remainder of the field should be covered with cotton patties before the dura is incised. If the basal craniectomy extends far anteriorly, the superior sagittal sinus is ligated and cut. To continue, the dura is resected step by step while pulling it caudally to avoid injury to brain structures. The incision is started at the anterior limit of the craniectomy so that resection of the dura on one or both sides can proceed to provide a clear view of the base of the frontal lobe. The resected piece of dura is marked and sent for serial histologic examination. The resulting dural defect is patched with fascia lata tucked between the bone and dural margins. The graft is additionally secured with a few anchoring sutures and fibrin glue. After the graft has been covered with silicone film, epithelialization of the lyophilized dura or the fascia lata occurs relatively quickly from the remaining mucosal rim. In a few weeks, the initially loose or sagging dural transplant changes into a firm, flat sheet of scar tissue. If resection of the anterior skull base extends beyond the fovea ethmoidalis and cribriform plate, a horizontal forehead and scalp flap conforming to the size of the cranial defect should be folded over to provide stable coverage of the duraplasty and epithelialization of the remaining orbital roof and fovea. The donor area of the scalp flap can be covered either with a split-thickness skin graft or by advancing other scalp flaps (Fig. 116-9).

Intracranial Approach to the Anterior Skull Base

Transfrontal Extradural Approach

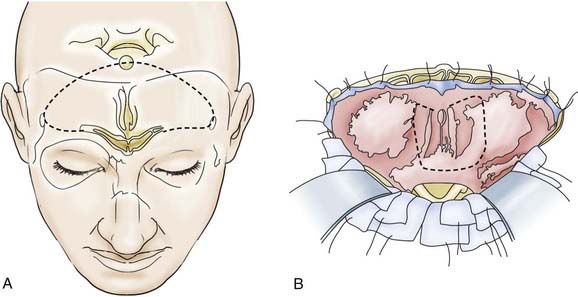

Depending on the extent of the lesion, a bitemporal coronal incision is made, and a unilateral or bifrontal craniotomy is performed. The extent of the latter depends on the site of the tumor. With midline lesions, the dura is mobilized on both sides of the crista galli and in part is sharply elevated from the cribriform plate. If necessary, the dura can be detached bilaterally as far as the lower sphenoid wing and tuberculum sellae (Fig. 116-10). With this maneuver, clear delineation of the anterior skull base is possible. This approach also permits good exposure of the frontal sinus, ethmoid cells, and sphenoidal sinus, supplemented if necessary by removal of the crista galli itself. This method also offers good exposure of the optic canal and the superior aspect of the orbital contents. The optic chiasm with the intradural portion of the optic nerve is not visualized with this approach. Lesions extending to the clivus are accessible by dissecting along the posterior wall of the sphenoidal sinus or the anterior wall of the sella. The endocranium is sealed off from the paranasal sinus system with a dural or fascial transplant—in some cases with a galea-periosteal flap that has a basal pedicle (Fig. 116-11).

Transfrontal Intradural Approach

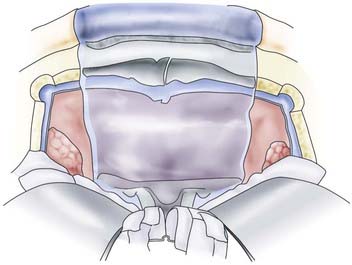

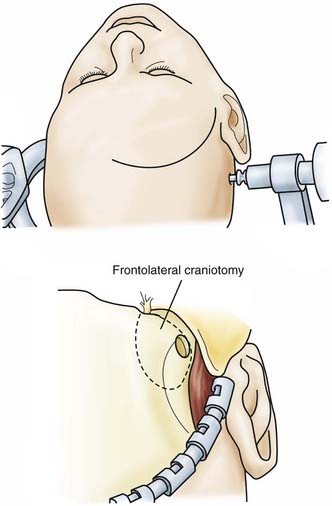

![]() For the frontolateral approach, the patient is positioned supine with the trunk elevated; the head is turned 10 degrees to the contralateral side, extended 15 to 20 degrees, and fixed in a Mayfield head holder. The frontolateral approach starts with a frontotemporal incision (usually on the right side) in front of the tragus, following just behind the hairline up to the midline (Fig. 116-12). A small craniotomy flap is created on one side close to the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. The dura is opened with a frontobasal incision. The arachnoid cisterns are opened progressively as the frontal lobe is gently retracted. Both optic nerves are exposed, along with the internal carotid artery (Fig. 116-13). Indications for the frontolateral approach include olfactory meningiomas, meningiomas of the planum sphenoidale and anterior clinoid, and suprasellar tumors such as meningiomas, craniopharyngiomas, and pituitary adenomas, among others (Video 116-2).

For the frontolateral approach, the patient is positioned supine with the trunk elevated; the head is turned 10 degrees to the contralateral side, extended 15 to 20 degrees, and fixed in a Mayfield head holder. The frontolateral approach starts with a frontotemporal incision (usually on the right side) in front of the tragus, following just behind the hairline up to the midline (Fig. 116-12). A small craniotomy flap is created on one side close to the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. The dura is opened with a frontobasal incision. The arachnoid cisterns are opened progressively as the frontal lobe is gently retracted. Both optic nerves are exposed, along with the internal carotid artery (Fig. 116-13). Indications for the frontolateral approach include olfactory meningiomas, meningiomas of the planum sphenoidale and anterior clinoid, and suprasellar tumors such as meningiomas, craniopharyngiomas, and pituitary adenomas, among others (Video 116-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree