CHAPTER 212 Birth Head Trauma

Incidence and Risk Factors

The incidence of major birth trauma such as fractures, paralysis, and lacerations is between 1 and 11.7 per every 1000 to 2000 live births.1–3 Perinatal death secondary to birth trauma alone is a rare event that occurs in 1 in 1000 to 2000 births.1 Many factors related to the fetus, the mother, and the birthing process have been correlated with an increased incidence of traumatic birth. Such factors include macrosomia, growth retardation, preterm labor, breech presentation, and multiparity.1,2,4–7

The mode of delivery has also been implicated in birth trauma. There is much debate in the obstetric literature regarding the efficacy and safety of assistive devices for vaginal delivery, such as forceps and vacuum extractors.8–11 As with all medical instruments, these instruments are safe when used in the appropriate manner by trained physicians. The indications for assisted vaginal delivery are delay, malrotation, or fetal distress in the second stage of labor. The cervix should be fully dilated, and the fetal head should be at the level of the ischial spines or below. There is, however, an increased risk for certain types of birth trauma associated with their use (discussed later).12–17 Operative vaginal delivery, either by forceps, vacuum, or converted cesarean section performed during labor, was associated with an increased incidence of intracranial hemorrhage when compared when spontaneous vaginal delivery.18 One would assume that having a lower threshold to proceed with cesarean section would lower the rate of birth trauma. An extensive study conducted by Puza and colleagues showed that this assumption was true because of the trend toward delivering neonates by cesarean section.3

Scalp Injury

In a newborn, scalp injury occurs in three distinct areas: the outer layers, the potential subgaleal space, and the subperiosteal plane. The most common scalp injury is caput succedaneum.4 This occurs in virtually all children, normally at the vertex. Rather than being a true injury, it is edema of the outer layers of the scalp, and it usually collects in the portion of the scalp that leads the way down the birth canal. To the obstetrician, it is known as chignon and is commonly associated with the use of vacuum extraction.4 It is generally noted immediately after birth and resolves within 24 hours. Rarely, it may have associated skin ecchymoses, abrasions, or lacerations.19 Soft cups used for vacuum extraction cause scalp injury less frequently than do rigid cups.8

Although rare, the most life-threatening scalp injury is a hematoma in the subgaleal plane.12,16,20 Plauche reported a mortality of 22.8% associated with this neonatal emergency.16 The galea aponeurotica extends from the supraorbital rims to the hairline posteriorly and laterally to the level of the ears. This sizable potential space can easily accommodate the entire blood volume of a neonate.

Three conditions put newborns at risk for the development of subgaleal hematoma.12 A coagulation defect or vitamin K deficiency after a routine or complicated delivery increases the risk for subgaleal hematoma. The third condition—and the most common—is a difficult delivery in which vacuum extraction is used. In Plauche’s review of 123 patients with subgaleal hematomas, vacuum extraction was used in 49% of the cases and forceps in 14%.16

The last type of scalp injury is cephalohematoma, which occurs in 1% to 2% of all births.21,22 It is an accumulation of blood between the periosteum and bone; therefore, the cranial sutures limit its expansion. The hemorrhage is thought to occur when the forces of labor acting on the neonatal head shear the periosteum away from the bone.21 Both the bone and the undersurface of the periosteum bleed, and a collection forms. The most common location is in the parietal region, but cephalohematoma can occur anywhere over the skull.

Usually, cephalohematomas are of no clinical significance and resolve spontaneously within a few weeks to months. Rarely, hyperbilirubinemia, anemia, or hemodynamic instability develops. There are a few reported cases of cephalohematomas that became infected.22–25 Infection may occur spontaneously, as a complication of fetal monitoring, or after sepsis or meningitis. Infection of a cephalohematoma can also lead to osteomyelitis, meningitis, and sepsis in the newborn. The most common infecting organism is Escherichia coli, and the infection usually occurs within 3 weeks. In this situation, a diagnostic tap or open irrigation and drainage are indicated.22 However, drainage of the hematoma is not generally advised because of the risk of introducing bacteria. In less than 5% of patients, the cephalohematoma calcifies. If it is large or cosmetically unpleasant, the parents may opt to have it removed. To do so, one merely burs the calcified lesion down to the outer layer of the skull. All bleeding should be judiciously controlled with bone wax and electrocautery.

Skull Fractures

Three types of skull fractures can occur in newborns: linear, depressed or “ping-pong,” and occipital osteodiastasis. The cause of skull fracture is a narrow pelvic passage or pressure against the promontory of the sacrum by forceps and vacuum extractors. The exact incidence in newborns is difficult to determine. Although skull fractures are demonstrable on plain radiographs and CT bone window scans, linear fractures can be difficult to visualize. It has been reported that linear skull fractures occur in as many as 10% of all births.21 Most linear skull fractures involve the parietal bone, although they can occur in the occipital and frontal bones as well. They usually heal within 2 to 3 months and require only a follow-up skull radiograph to rule out a growing skull fracture.13–15 Growing fractures are associated with underlying dural laceration and brain injury (see Chapter 214). Such fractures associated with birth trauma are rare and have been reported in only a few cases.13 Vacuum extractions can rupture suture lines and result in a growing fracture.26

Anywhere from 5.4% to 25% of linear skull fractures have an associated cephalohematoma.4,27,28 In such patients, CT should be performed to rule out an epidural hematoma, which can occasionally require surgical removal (discussed in the next section).

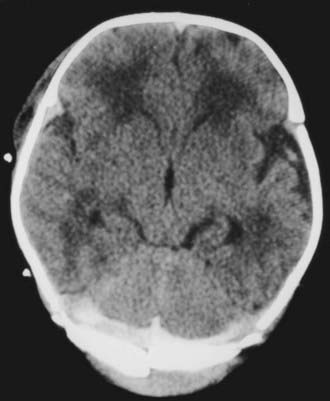

Depressed skull fractures are unique to the newborn period. Because of the thin, pliable nature of a newborn’s skull, the bone cortex indents or buckles inward. True indentation is rare, however, and skull fracture is often observed on CT scans or at surgical repair of a depressed fracture (Fig. 212-1). As with linear fractures, the parietal bone is the most common location.

FIGURE 212-1 Axial computed tomography bone window scan showing a depressed fracture caused by forceps.

For all children with such lesions, CT of the head should be performed to rule out an associated intracranial hemorrhage. There is debate whether these lesions need to be surgically elevated in an otherwise asymptomatic child. There are case reports in the literature of a breast pump, digital pressure, and vacuum extractor being used to elevate these fractures.29–32 However, depressed fractures in newborns often improve and become elevated spontaneously. Loeser and coworkers recommend surgical intervention only for children who have bone fragments in the cerebrum, neurological deficits with or without increased intracranial pressure, or an associated dural tear with leakage of cerebrospinal fluid beneath the galea.33 They would also consider surgical elevation in neonates who failed conservative management, had poor cosmetic results, or had unreliable long-term follow-up.

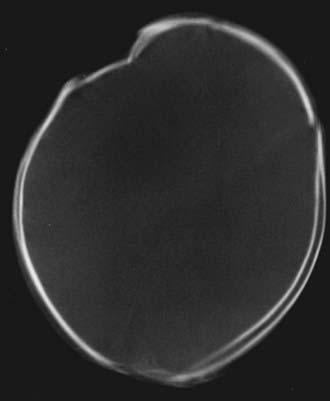

During a difficult delivery, particularly after a forceps breech delivery, it is theorized that the synchondrosis opens between the squamous and condylar portions of the occipital bone.12,34,35 In this manner, the squamous bone is able to slide anteriorly, thereby allowing excessive vertical molding of the skull. This separation of the occipital bones is known as occipital osteodiastasis. Although it allows the fetal head to pass more easily through the birth canal, it is stressful on the intracranial contents and often results in tentorial and falcine tears, with damage to draining venous structures. In some cases, the squamous portion may sustain a vertical fracture resulting from compression at breech delivery (Fig. 212-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree