30 Brachial Plexopathy

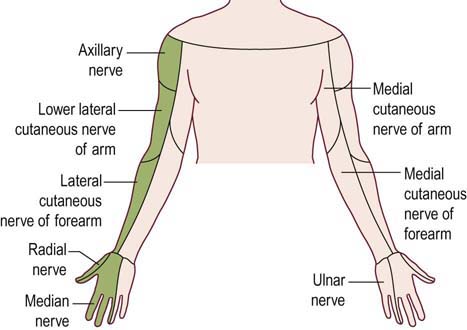

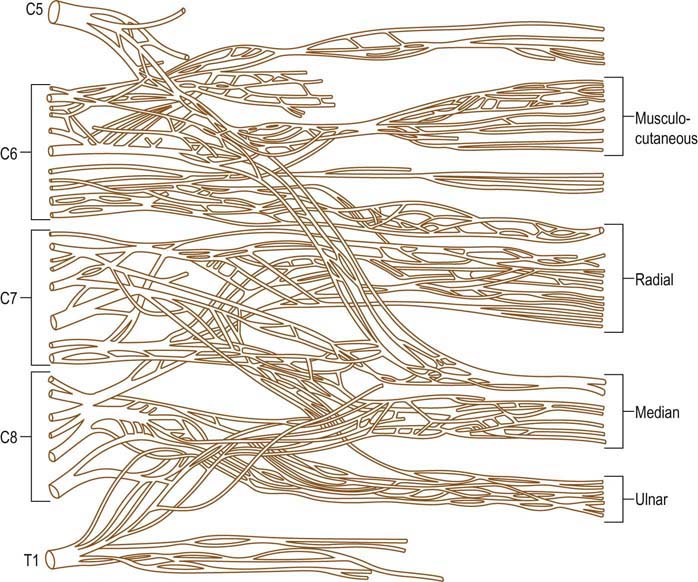

The brachial plexus is a complicated anatomic structure formed by the ventral rami of the lower cervical and upper thoracic nerve roots. Different fascicles from those roots intermix widely within the plexus to ultimately form all the nerves of the upper extremity (Figure 30–1). In cases of suspected brachial plexopathy, nerve conduction studies and electromyography (EMG) often are used to localize the lesion accurately and to assess its severity. Notwithstanding its usefulness, the electrophysiologic evaluation of brachial plexopathy is demanding for the electromyographer. Detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the upper extremity roots, plexus, and peripheral nerves is required. Extensive bilateral studies, with emphasis on the sensory conduction studies and needle EMG, frequently are needed to localize the lesion. Proper localization is key, not only to exclude a disorder of the nerve roots, which may closely resemble brachial plexopathy clinically, but also to suggest possible etiologies, as certain disorders preferentially affect different parts of the brachial plexus. In addition, assessing the severity is important, especially in cases of trauma, where the results often help decide whether surgery should be considered.

FIGURE 30–1 Microdissection of brachial plexus anatomy.

(From Kerr, A.T., 1918. Am J Anat 23, 285, with permission.)

Anatomy

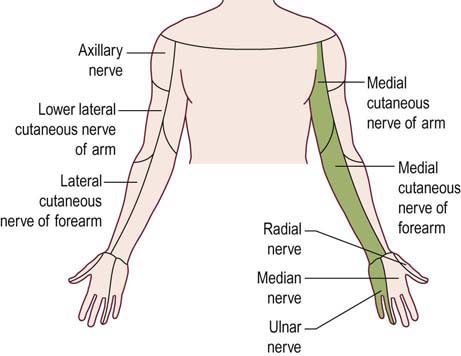

The brachial plexus is located between the lower neck and axilla, running behind the scalene muscles proximally and behind the bony clavicle and the pectoral muscles distally. The plexus is divided anatomically into roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and finally nerves (Figure 30–2), although, strictly speaking, the roots and peripheral nerves are not considered part of the plexus proper. Two important nerves, the long thoracic and dorsal scapular, originate directly from the roots, proximal to the brachial plexus. The long thoracic nerve comes off the C5–C6–C7 roots, innervating only the serratus anterior muscle. The dorsal scapular nerve is formed primarily from the C5 root and less so from the C4 root, innervating the rhomboid muscles. After the take-off of these two nerves, the anterior rami of the C5–T1 nerve roots come together above the level of the clavicle to form the three trunks of the brachial plexus. The upper trunk is formed from the C5–C6 roots. The C7 root continues as the middle trunk, and the lower trunk is formed from the C8–T1 roots.

FIGURE 30–2 Brachial plexus anatomy.

The brachial plexus is divided into roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and finally nerves.

(From Hollinshead, W.H., 1969. Anatomy for surgeons, volume 2: the back and limbs. Harper & Row, New York, with permission.)

All major nerves in the upper extremity originate either from the cords and trunks of the brachial plexus or, less commonly, directly from the roots (Table 30–1). Although the brachial plexus is generally formed from the C5–T1 nerve roots, anomalies are not infrequent. For example, in some individuals the brachial plexus is formed predominantly from the C4–C7 roots and is said to be prefixed. In others the plexus is postfixed, receiving most of its innervation from the C6–T2 roots.

Table 30–1 Innervation of Major Upper Extremity Nerves

| Nerve | Innervation |

|---|---|

| Dorsal scapular | C4–C5 roots directly |

| Long thoracic | C5–C6–C7 roots directly |

| Suprascapular | Upper trunk |

| Radial | Posterior cord |

| Axillary | Posterior cord |

| Thoracodorsal | Posterior cord |

| Musculocutaneous | Lateral cord |

| Median | Lateral and medial cords |

| Ulnar | Medial cord |

| Medial antebrachial cutaneous | Medial cord |

| Medial brachial cutaneous | Medial cord |

Clinical

Upper Trunk Plexopathy

The upper trunk is formed from the C5–C6 roots. Thus, upper trunk lesions result in weakness of nearly all muscles with C5–C6 innervation. Most affected are the deltoid, biceps, brachioradialis, supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. Muscles that receive partial upper trunk innervation, such as the pronator teres (C6–C7) and triceps (C6–C7–C8), may be partially affected. Sensory loss involves the lateral arm, lateral forearm, lateral hand, and thumb. This territory corresponds to the sensory distributions of the axillary and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerves, as well as the median and radial sensory branches to the thumb and index finger (Figure 30–3). The biceps and brachioradialis tendon jerks are depressed or absent, but the triceps reflex is spared.

Lower Trunk Plexopathy

The lower trunk is formed from the C8–T1 roots. The entire ulnar nerve, the medial brachial cutaneous nerve, and the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve are ultimately supplied from fibers passing through the lower trunk. In addition, both the median and radial nerves receive partial motor innervation from the lower trunk. Accordingly, lower trunk lesions involve all ulnar muscles, in addition to median C8–T1-innervated muscles (e.g., abductor pollicis brevis [APB], flexor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum profundus) and radial C8-innervated muscles (e.g., extensor indicis proprius [EIP], extensor pollicis brevis). Sensory loss involves the medial arm, medial forearm, medial hand, and fourth and fifth fingers. This territory corresponds to the distribution of the medial brachial cutaneous, medial antebrachial cutaneous, ulnar sensory, and dorsal ulnar cutaneous sensory nerves (Figure 30–4). In pure lower trunk plexopathies, there are no reflex abnormalities.

Etiology

Traumatic Brachial Plexopathy

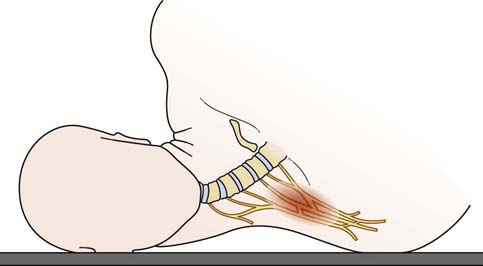

Most traumatic plexopathies are the result of traction and stretch injuries. Injuries in which the head is pushed away from the shoulder (e.g., the head and shoulder striking the pavement when a person is thrown from a moving vehicle) typically result in upper plexopathies, affecting the C5–C6 fibers (Figure 30–5). Such injuries result in characteristic weakness of shoulder abduction, elbow flexion, and arm supination, known as Erb’s palsy. This is also the most common type of brachial plexopathy seen in newborns, presumably as a result of the head being delivered down, away from the shoulder. The most common risk factor for an Erb’s palsy in a newborn is shoulder dystocia in a large infant. In contrast, injuries in which the arm and shoulder are pulled up typically result in lower plexopathies, affecting the C8–T1 fibers. Severe hand weakness, known as Klumpke’s palsy, characteristically occurs in these latter injuries, with preservation of upper arm and shoulder girdle muscles. One of the most common scenarios in which this occurs is when an individual (often unconscious) is dragged by one arm.

Postoperative Brachial Plexopathy

In lesions of the lower trunk, patients note sensory disturbance in the fourth and fifth fingers (ulnar distribution), which may continue up the medial forearm and arm (medial brachial and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves). Weakness involves all C8–T1 muscles, including median and ulnar hand intrinsics, all forearm long finger flexors (Figure 30–6), and, less so, the finger extensors (principally the extensors to the thumb and index finger). In some cases, pain may be a prominent symptom. Because the presumed injury is secondary to stretch and compression, without any tearing or shearing of nerve and basement membrane, most patients make a good recovery over several months. Rarely, patients may not recover completely; occasionally, patients are left with chronic pain that is difficult to treat.

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

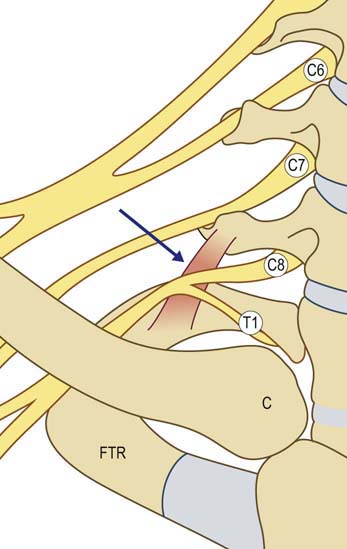

Most cases of true neurogenic TOS are caused by a fibrous band that runs from a rudimentary cervical rib to the first thoracic rib, entrapping the lower trunk of the brachial plexus (Figure 30–7). Accordingly, sensory and motor loss develops in the C8–T1 distribution. Anatomically, the fibrous band most often preferentially affects the T1 fibers. This results in a characteristic pattern of signs and symptoms, including prominent wasting and weakness of the thenar and, less prominently, the hypothenar muscles (Figure 30–8). The explanation for the relative vulnerability of the thenar muscles is not completely clear, but it may be that the thenar muscles are more T1 innervated, whereas the hypothenar muscles receive more C8 innervation.

FIGURE 30–7 Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome anatomy.

(Adapted from Levin, K.H., Wilbourn, A.J., Maggiano, H.J., 1998. Cervical rib and median sternotomy-related brachial plexopathies: a reassessment. Neurology 50, 1407–1413, with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree