CHAPTER 203 Brainstem Glioma

History and Definition

Brainstem gliomas (BSGs) are a histologically heterogeneous group of tumors that are primarily defined by their location. They present unique challenges to the operative neurosurgeon, are some of the most difficult-to-treat pediatric brain tumors, and require a multidisciplinary approach. However, progress has been made since the beginning of the 20th century, when diffuse pontine glioma (DPG), one of the most commonly encountered tumors in this group, was viewed with a sense of hopelessness.1 Contemporary imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has allowed better anatomic localization and classification of these tumors. Although DPG still remains a fatal tumor, multimodality treatment of the other brainstem tumors provides long-term survival in the majority of these patients.

By definition, BSGs are tumors that arise within the anatomic structures that make up the brainstem. Advances in neuroimaging have allowed us to better define these tumors, and a number of different classification schemes that have also incorporated some of their known biologic features have been suggested.2–4 In addition to DPG, definition plus classification into tectal, focal pontine, and midbrain tumors, dorsal exophytic tumors, and tumors of the cervicomedullary junction (CMJ) is practical and most useful.

Epidemiology

BSGs account for 10% to 20% of primary pediatric brain tumors and about 25% of tumors arising in the posterior fossa, with an incidence of 150 to 300 new cases per year in the United States. The mean age at diagnosis in several large series is 6.5 to 9 years (ranging from several months to the late teens), without a predilection for gender or race and without outstanding genetic inheritance.5 DPGs are the most commonly seen BSGs in the pediatric population and represent approximately 60% to 75% of these tumors.

Signs and Symptoms

Diffuse Pontine Glioma

Most children with DPG have evidence of cerebellar dysfunction (87%), multiple lower cranial nerve palsies (77%), and motor paresis and sensory changes secondary to long-tract involvement (53%).5 The presence of this classic triad almost always makes the diagnosis on a clinical basis alone.

The extent and duration of symptoms are usually less than expected given the size of the tumor on imaging studies and the involved brainstem structures. The duration of symptoms is relatively short, and 94% of patients will have had symptoms for less than 6 months at time of initial evaluation. The duration of symptoms is a predictor of outcome, with a better outcome if symptoms were present for 6 months or longer and a significantly worse outcome for tumors with symptoms lasting 1 month or less.5

Tectal Glioma

Tectal gliomas are considered a subgroup of focal BSGs and are most often initially manifested as hydrocephalus secondary to aqueductal stenosis.6–8 Despite involvement of the quadrigeminal plate, the classic Parinaud syndrome is not as commonly seen with these tumors as with pineal tumors causing compression on this structure. Most patients have had a long-standing history of headaches and on occasion “clumsiness” or ataxia, and imaging studies are usually obtained in the course of investigation of the headaches, thus establishing the diagnosis. Tectal lesions may in rare cases be accompanied by oculomotor palsy.6 Many patients will have macrocephaly on examination, in addition to the other neurological findings. Rapidly progressive symptoms should raise concern about the biologic behavior and pathology of these tumors. Atypical or more aggressive tectal gliomas tend to occur in younger patients.9

Focal Tumors

Focal tumors can arise anywhere in the brainstem and cause symptoms that reflect the involved anatomic structures. Midbrain lesions are commonly manifested as hydrocephalus and focal neurological deficits, depending on the location of the tumor. Focal pontine lesions are characterized by isolated facial palsies, long-tract signs, or hearing loss. Lesions in the medulla oblongata involve the lower cranial nerves and can cause respiratory difficulties (including apnea), recurrent upper respiratory tract infections and pneumonia, and swallowing difficulties with aspiration of food and saliva. In infants, failure to thrive may be the initial symptom. The gag reflex may be affected, and tongue asymmetry might be present.10

Exophytic Tumors

These tumors differ from the other subgroups of BSGs in that they are the only BSG originating from the subependymal glia in the floor of the fourth ventricle and growing posteriorly, thereby filling the fourth ventricle.11 Only about 10% of the tumor mass growth occurs in the brainstem, which is spared for a long time and thus results in very gradually progressive symptoms. Careful history taking commonly reveals that the initial symptoms have been present for longer than 1 year.12 Obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways in the fourth ventricle is not uncommon and leads to intractable vomiting and failure to thrive in infants and headaches, vomiting, and ataxia in older children. Papilledema and torticollis are frequently present on examination and indicate increased intracranial pressure and chronic tonsillar herniation.12

Diagnosis

Computed Tomography

CT can show the rare presence of calcifications in brainstem tumors better than MRI can. If present, this usually implies an atypical BSG rather than a DPG.15

Single-photon emission CT using thallium 201 shows accumulation of the radioactive tracer in the tumor, which is 90% specific for a BSG but is not correlated with tumor grade, enhancement patterns of other contrast media, or necrosis.16

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

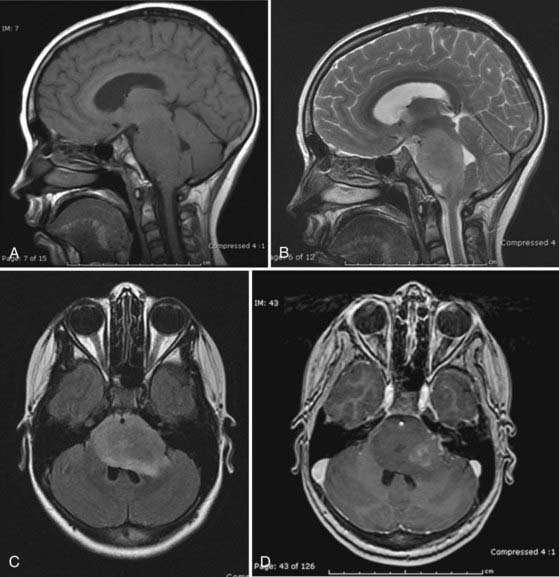

MRI is the preferred method for imaging brainstem tumors. DPGs are generally hypointense on T1-weighted sequences with diffuse enlargement of the pons and indistinct margins. T1-weighted images tend to underestimate the true extent of the tumor, which is best appreciated on T2-weighted images and is hyperintense on these sequences. The tumors characteristically engulf the basilar artery ventrally. Contrast enhancement is variable and may be nonhomogeneous inside or around the tumor or may be absent altogether in about a third of patients,15 so it is of limited prognostic value (Fig. 203-1).17 Dissemination along the CSF pathways is rare, although it can be seen at diagnosis in about 15% of cases, and therefore it is imperative that the entire CNS axis be imaged at time of initial diagnosis.

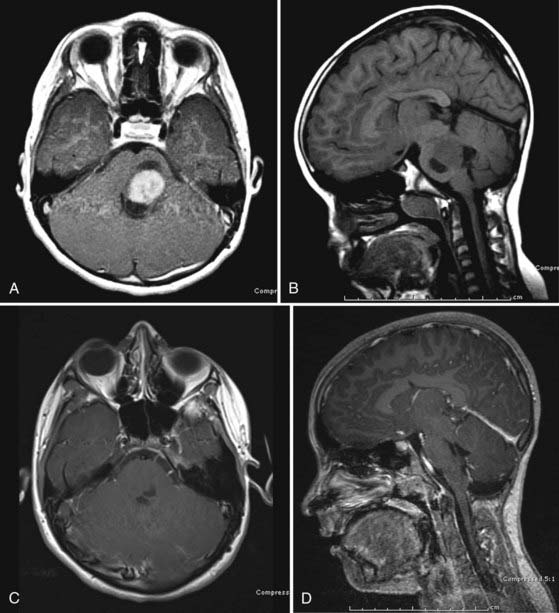

Focal lesions appear to be better circumscribed and are generally isointense on T1-weighted sequences and brightly enhancing. They occupy less than 50% of a brainstem region, thus leading to the designation “focal.” Focal tumors are more common in the midbrain and medulla and least common in the pons; they are usually well delineated without a large amount of edema or evidence of focal infiltration (Fig. 203-2).2,17

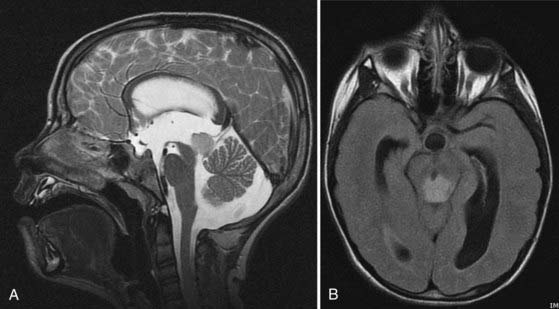

Tectal tumors are infiltrating lesions in the tectal plate that are poorly delineated and rarely enhance. They are usually hypointense on T1-weighted images and bright on T2-weighted sequences (Fig. 203-3). Size larger than 2 cm and enhancement are features associated with a worse outcome and suggest an atypical tectal tumor.18

CMJ tumors are similar in appearance to infiltrating gliomas, with evidence of growth in the medulla and cervical spinal cord. The epicenter is usually at the foramen magnum area, and there is frequently a large exophytic component that is either obstructing the outlet of the fourth ventricle or located in the cerebellopontine angle and causing compression and distortion of the lower medulla (Fig. 203-4).

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients with BSG has shown lower N-acetylaspartate levels than in normal controls, which may be helpful in distinguishing them from the benign diffuse pontine enlargements seen in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis.19,20 Lesions associated with NF1 tend to be multifocal, frequently also extend into the cerebellar peduncles, and may show contrast enhancement.21

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography has been used to differentiate between low-grade and high-grade lesions and also to evaluate response to treatment. Diffusion tensor imaging has recently been introduced in an attempt to identify involvement of white matter tracts by the tumor and potentially aid in the surgical management of these tumors.22

Differential Diagnosis

Most diffuse lesions in the pediatric population are fibrillary infiltrating gliomas, but the histologic grade can vary considerably between low grade (37%), anaplastic (56%), and glioblastoma (5%).5 The true incidences are not known because of the low biopsy and resection rate of these tumors. Other pathologies include pilocytic astrocytoma, infantile ganglioglioma, ganglioglioma and gangliocytoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, and atypical teratoid-rhabdoid tumor.

Pathobiology

Patients with NF1 may have intrinsic lesions in the brainstem that at least radiographically resemble diffuse BSGs but appear to follow a more benign course. Focal lesions in this context may be indolent.23 In a series of 21 patients with brainstem masses and NF1, only 9 had radiographic and 3 had clinical disease progression with a follow-up period of 3.75 years.24–26

Fibrillary Astrocytoma

Most BSGs are diffuse fibrillary astrocytomas. However, grading is difficult because of the issue of sampling and the relative rarity of specimens available for pathologic examination. They are predominantly composed of fibrillary neoplastic astrocytes with nuclear atypia. Mitotic activity (Ki-67/MIB-1 labeling index) is usually less than 4%, and necrosis and microvascular proliferation can be present. Molecular characterization commonly shows TP53 mutations (>60%), although they are not a predictor of outcome, loss of heterozygosity of 22q (in about a third), and less often a number of other chromosomal abnormalities.27

The cytogenetic abnormalities of diffuse BSGs resemble those of adult malignant gliomas, including TP53 mutations and mutated epidermal growth factor receptor genes. In a study of six patients, 50% had multiple abnormalities and progressed rapidly.28 ERBB1 was found to be overexpressed in some DPGs, and the grade of amplification correlated with the grade of the tumor.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree