A. Therapeutic approach.

1. Dexamethasone therapy. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends consideration of dexamethasone in the treatment of infants and children 2 months of age and older with proven or suspected bacterial meningitis on the basis of findings on CSF examination. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Practice Guidelines for the Management of Bacterial Meningitis and the European Federation of Neurological Societies Guideline on the Management of Community-Acquired Bacterial Meningitis recommend the use of dexamethasone in adults with suspected or proven pneumococcal meningitis (based on CSF gram-positive diplococci or blood or CSF cultures that are positive for Streptococcus pneumoniae). The IDSA Practice Guidelines also acknowledge that some authorities would initiate dexamethasone in all adults with suspected bacterial meningitis because the etiologic organism is not known at initial evaluation. Recent studies have demonstrated a favorable trend toward reduced rates of death and hearing loss and no evidence that dexamethasone was harmful in meningococcal meningitis. In clinical trials, dexamethasone improves the outcome of meningitis. In experimental models of bacterial meningitis, dexamethasone inhibits synthesis of the inflammatory cytokines, decreases leakage of serum proteins into the CSF, minimizes damage to the blood–brain barrier (BBB), and decreases CSF outflow resistance. Dexamethasone also decreases brain edema and intracranial pressure (ICP).

The recommended dosage of dexamethasone is 0.15 mg/kg intravenous (IV) every 6 hours for the first 4 days of therapy. The initial dose of dexamethasone should be given before or at least with the initial dose of antimicrobial therapy for maximum benefit. Dexamethasone is not likely to be of much benefit if started >24 hours or more after antimicrobial therapy has been initiated. The concomitant use of a histamine-2 receptor antagonist is recommended with dexamethasone to avoid gastrointestinal bleeding.

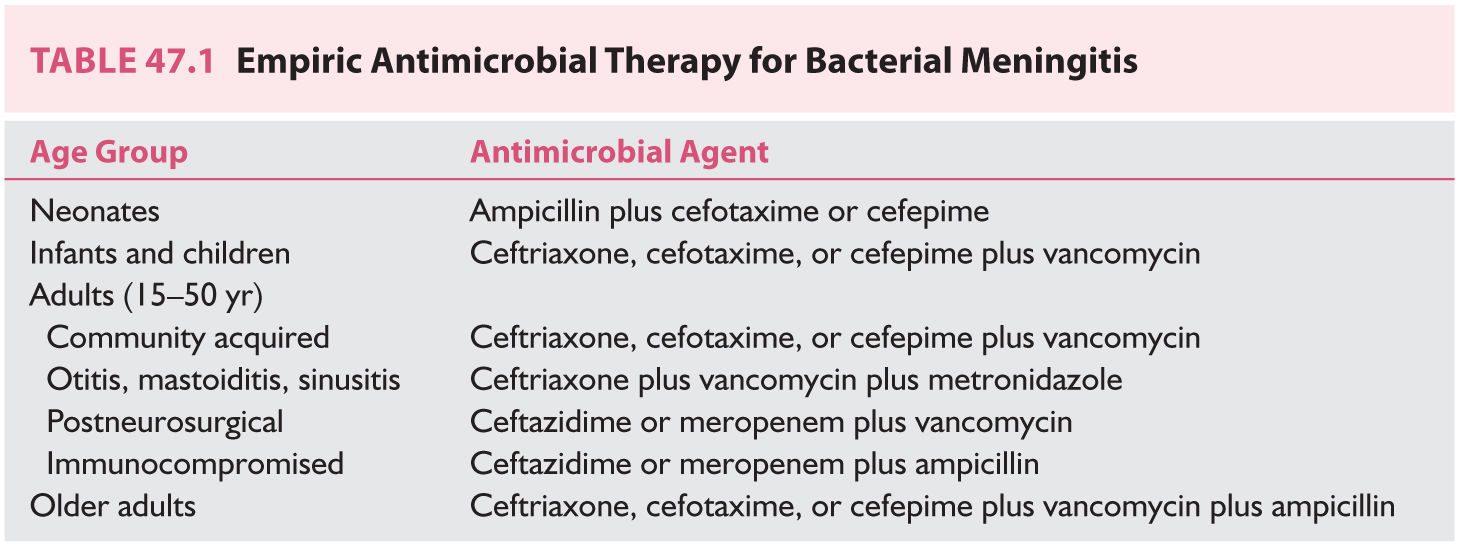

2. Antimicrobial therapy. If bacterial meningitis is suspected, antimicrobial therapy must be initiated immediately. This should be done before the performance of computed tomography (CT) or lumbar puncture. Initial antimicrobial therapy is empiric and is determined by the most likely meningeal pathogen according to the patient’s age and underlying condition or predisposing factors.

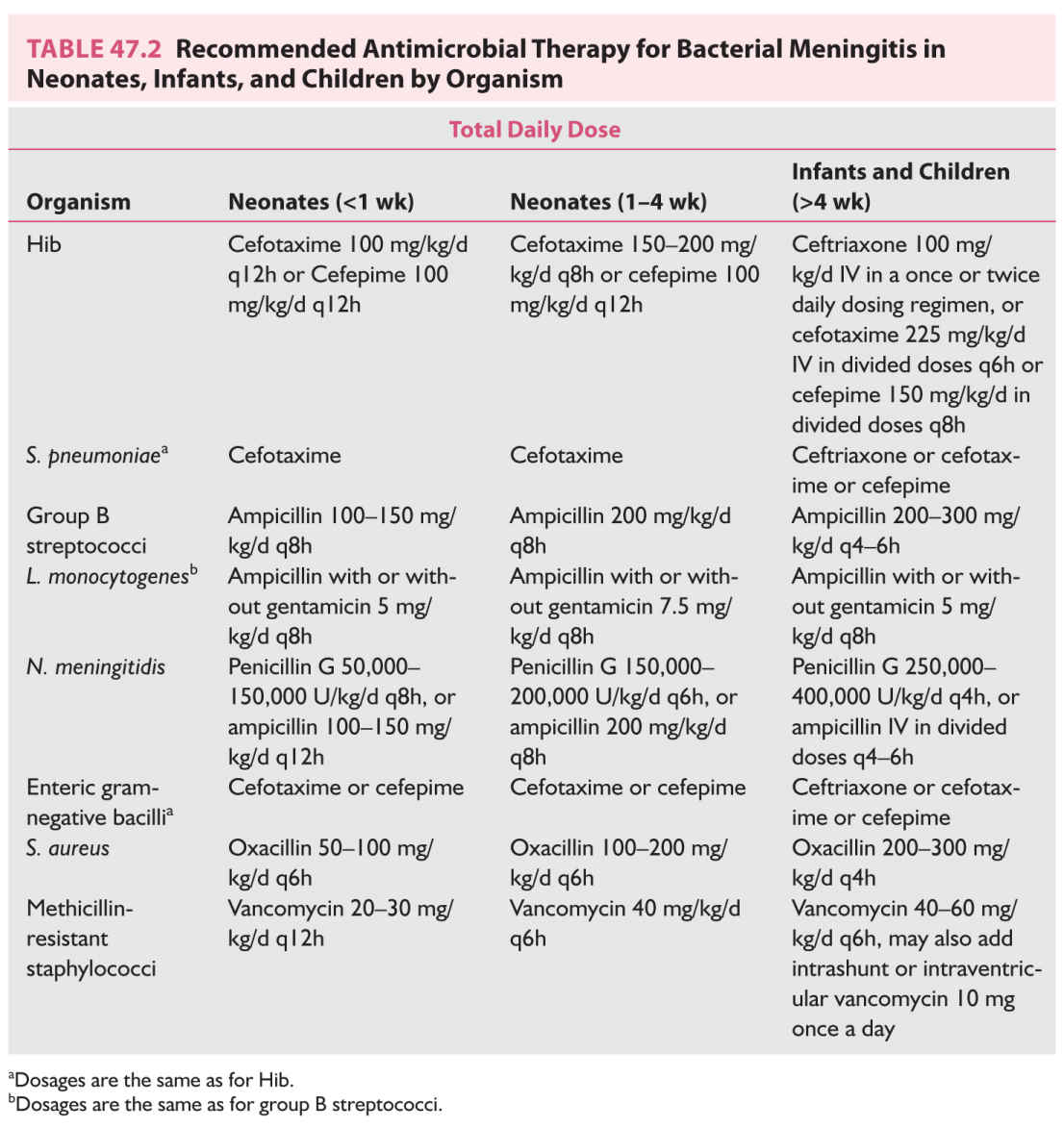

a. The most likely etiologic organisms of bacterial meningitis in neonates are group B streptococci, enteric gram-negative bacilli (Escherichia coli), and Listeria monocytogenes. Empiric therapy for bacterial meningitis in a neonate should include a combination of ampicillin and either a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime or cefepime).

b. Empiric therapy for community-acquired bacterial meningitis in infants and children should include coverage for S.pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis. A third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin (ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, or cefepime) and vancomycin are recommended as initial therapy for bacterial meningitis in children in whom the etiologic agent has not been identified. Cefuroxime, also a third-generation cephalosporin, is not recommended for therapy for bacterial meningitis in children because of reports of delayed sterilization of CSF cultures associated with hearing loss in children treated with cefuroxime.

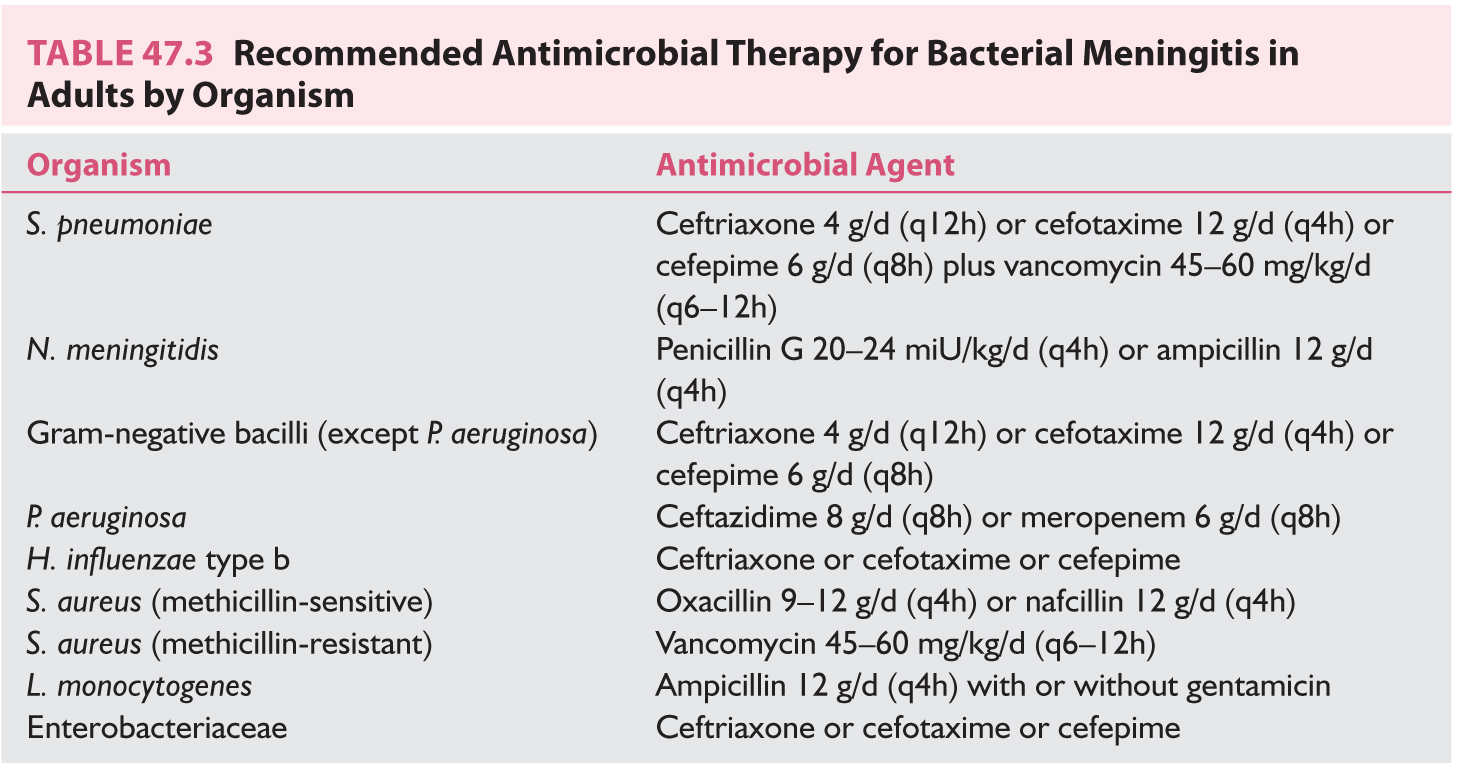

c. Empiric therapy for community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults (15 to 50 years of age) should include coverage for S. pneumoniae and N. meningitidis. A third-generation cephalosporin (ceftriaxone or cefotaxime) or a fourth-generation cephalosporin (cefepime) plus vancomycin is recommended for empiric therapy. All CSF isolates of pneumococci and meningococci should be tested for antimicrobial susceptibility. Cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, or cefepime is recommended for relatively resistant strains of pneumococci (penicillin minimal inhibitory concentrations [MIC], 0.1 to 1.0 mg/mL and MICs of cefotaxime or cefepime ≤0.5 mg/mL). For highly penicillin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis (MIC >1.0 mg/mL), a combination of vancomycin and a third-generation or fourth-generation cephalosporin is recommended. Penicillin G or ampicillin can be used for meningococcal meningitis.

d. Initial therapy for meningitis in postneurosurgical patients should be directed against gram-negative bacilli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus. Ceftazidime or meropenem is recommended for management of gram-negative bacillary meningitis in neurosurgical patients. Ceftazidime is the only cephalosporin with sufficient activity against P. aeruginosa in the central nervous system (CNS). Vancomycin should be added until infection with staphylococci is excluded.

e. In infants, children, and adults with CSF ventriculoperitoneal shunt infections, initial therapy for meningitis should include coverage for coagulase-negative staphylococci and S. aureus. The assumption can be made that the organism will be resistant to methicillin; therefore, initial therapy for a shunt infection should include IV vancomycin. Intrashunt or intraventricular vancomycin may also be needed to eradicate the infection.

f. In immunocompromised patients, the infecting organism can be predicted on the basis of the type of immune abnormality. In patients with neutropenia, initial therapy for bacterial meningitis should include coverage for L. monocytogenes, staphylococci, and enteric gram-negative bacilli. Patients with defective humoral immunity and those who have undergone splenectomy are unable to mount an antibody response to a bacterial infection or to control an infection caused by encapsulated bacteria. These patients are at particular risk of meningitis caused by S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), and N. meningitidis.

g. The most common organisms causing meningitis in the older adult (50 years or older) are S. pneumoniae and enteric gram-negative bacilli; however, meningitis caused by Listeria organisms and Hib are increasingly recognized. The recommended initial therapy for meningitis in the older adult is either ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, or cefepime in combination with vancomycin and ampicillin. Table 47.1 lists empiric antimicrobial therapy for bacterial meningitis by age group. Tables 47.2 and 47.3 list the recommended antimicrobial therapy for bacterial meningitis in neonates, infants and children, and adults by meningeal pathogen.

3. Management of increased ICP. Increased ICP is an expected complication of bacterial meningitis and should be anticipated.

a. Elevation of the head of the bed 30 degrees.

b. Hyperventilation to maintain Paco2 between 30 and 35 mm Hg.

c. Mannitol.

(1) Children. 0.5 to 2.0 g/kg infused over 30 minutes and repeated as necessary.

(2) Adults. 1.0 g/kg bolus injection and then 0.25 g/kg every 2 to 3 hours. A dose of 0.25 g/kg appears as effective as a dose of 1.0 g/kg in lowering ICP. The main exception is that the higher dose has a longer duration of action. Serum osmolarity should not be allowed to rise above 320 mOsm/kg.

d. Pentobarbital.

(1) Loading dose. 10 mg/kg over 30 minutes.

(2) 5 mg/kg/hour for 3 hours, supplemented with 200-mg IV boluses until a burst-suppression pattern is obtained on an EEG.

(3) Maintenance dosage. 1 mg/kg/hour by constant IV infusion.

4. Seizure activity is such a common complication of bacterial meningitis in adults, especially pneumococcal meningitis, for which prophylactic anticonvulsant therapy is not unreasonable.

a. Prophylactic therapy. Phenytoin is administered at a dosage of 18 to 20 mg/kg at a rate no faster than 50 mg/minute. Propylene glycol, the diluent of IV phenytoin, can cause bradycardia, hypotension, and cardiac dysrhythmias. IV phenytoin should be administered via central access while the ECG and BP are monitored. If these side effects are observed, the rate of administration should be decreased. It is recommended that phenytoin be administered no faster than 25 mg/minute in the elderly.

Fosphenytoin, the prodrug to phenytoin, is administered at a dosage of 18 to 20 mg (phenytoin equivalents) PE per kg at a rate no faster than 150 mg/minute. IV fosphenytoin does not contain propylene glycol and thus can be administered at a faster rate than phenytoin. A standard maintenance dosage is 100 mg of phenytoin or 100 mg PE of fosphenytoin every 8 hours. A serum concentration of 10 to 20 mg/mL should be maintained.

Levetiracetam is an alternative option for parenteral seizure prophylaxis therapy. The loading dose is 1,000 to 1,500 mg intravenously, followed by a maintenance dose of 500 mg every 12 hours. Levetiracetam dosing should be adjusted for creatinine clearance.

b. Status epilepticus.

(1) Lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg for adults; 0.05 mg/kg/dose for children) or diazepam (5 to 10 mg for adults; 0.2 to 0.3 mg/kg/dose for children) is administered IV.

(2) Phenytoin is administered in a dose of 18 to 20 mg/kg as described in Section A.4.a under Bacterial Meningitis. Fosphenytoin is administered in a dose of 20 mg PE/kg as described in Section A.4.a under Bacterial Meningitis. If seizures are not controlled, a repeat bolus of 10 mg PE/kg fosphenytoin or 500 mg phenytoin can be given.

(3) If phenytoin fails to control seizure activity, phenobarbital is administered intravenously at a rate of 100 mg/minute to a loading dose of 20 mg/kg. The loading dose of phenobarbital for children is also 20 mg/kg. The most common adverse effects of phenobarbital loading are hypotension and respiratory depression. Before phenobarbital loading, ensure that an endotracheal tube has been placed and mechanical ventilation begun. The primary reason for failure to control seizure activity is either that anticonvulsants are administered in subtherapeutic dosages or, as is the case for phenobarbital, the rate of administration is too slow.

(4) For more information on the management of refractory status epilepticus, see Chapters 42, 43, and 63.

5. Fluid management. Most children with bacterial meningitis have hyponatremia (serum sodium concentration <135 mEq/L) at the time of admission. For this reason, fluid restriction to correct the serum sodium level is important, but this must be done taking into consideration the adverse effects of hypovolemia on cerebral perfusion pressure. The recommended initial rate of IV fluid administration is approximately three-fourths normal maintenance requirements, or approximately 1,000 to 2,000 mL/m2/day. A 5% dextrose solution with one-fourth to one-half normal saline solution and 20 to 40 mEq/L potassium is recommended. The volume of fluids administered can be gradually increased when serum sodium concentration increases to >135 mEq/L.

B. Expected outcome. Despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy, patients with bacterial meningitis are very sick. Prognosis depends on age, underlying or associated conditions, time from onset of illness to institution of appropriate antimicrobial therapy, the infecting organism, and the development of brain edema, coma, arterial and venous cerebrovascular complications, hydrocephalus, or seizures. Pneumococcal meningitis has the worst prognosis, and a poor prognosis is associated with the extremes of age.

C. Prevention.

1. Rifampin is recommended for all close contacts with a patient who has meningococcal meningitis. Rifampin is given in divided doses at 12-hour intervals for 2 days as follows: adults, 600 mg; children, 10 mg/kg; neonates (younger than 1 month), 5 mg/kg. It should not be given during pregnancy. Pregnant and lactating women may be given intravenous or IV ceftriaxone (a single injection of 250 mg).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that adolescents and college freshmen be vaccinated against meningococcal meningitis with the tetravalent (Men A, C, W135, Y) meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine. This vaccine does not include serotype B.

2. The vaccination of infants with the Hib conjugate vaccine has greatly decreased the incidence of Hib. Rifampin prophylaxis should be given to children younger than 4 years of age who have not been fully vaccinated against Hib disease and who come in contact with a patient with Hib meningitis. It is recommended for all adults who have close contact with the patient and for the patient, because the organism usually is not eradicated from the nasopharynx with systemic antimicrobial therapy. Rifampin in the following dosages is recommended: adults, 20 mg/kg/day orally for 4 days; children, 20 mg/kg/day orally (maximum 600 mg/day) for 4 days; and neonates (younger than 1 month), 10 mg/kg/day for 4 days. Rifampin is not recommended for pregnant women.

HERPES ENCEPHALITIS

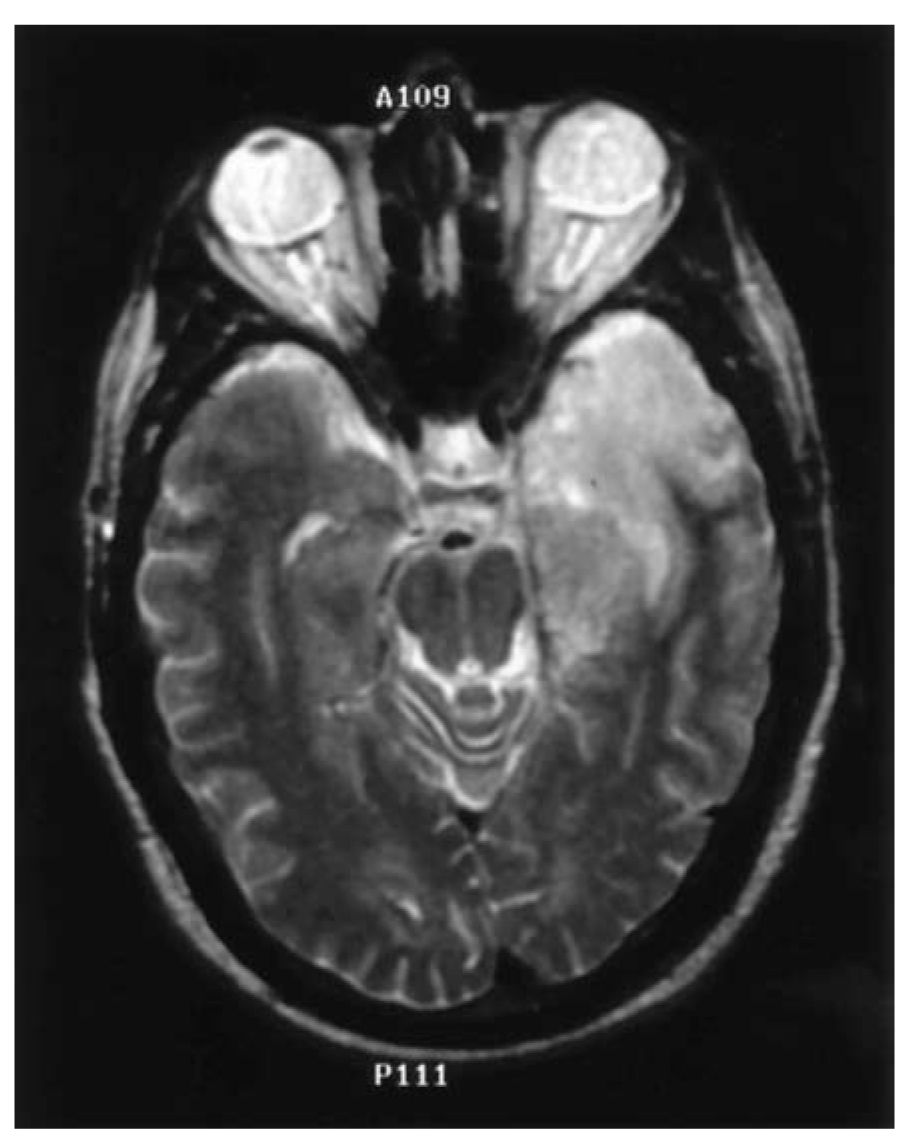

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain parenchyma. Herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) is the principal cause of herpes encephalitis. Initial infection occurs either after exposure to infected saliva or respiratory secretions, the virus gaining access to the CNS along the olfactory nerve and tract into the limbic lobe, or as a result of reactivation of latent virus from the trigeminal ganglion. Virus is transmitted from infected persons to other persons only through close personal contact. The typical clinical presentation is a several-day history of fever and headache followed by memory loss, confusion, olfactory hallucinations, and seizures. The hallmark sign is a focal neurologic deficit suggestive of a structural lesion in the frontotemporal area. On CT scans, there is a low-density lesion within the temporal lobe with mass effect. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the infection appears as an area of high signal intensity on T2-weighted (Fig. 47.1), diffusion-weighted, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images. Examination of the CSF shows a lymphocytic pleocytosis (with an average WBC count of 50 to 500 cells per mm3), elevation in protein concentration, and normal or mildly decreased glucose concentration. CSF should be sent for the PCR assay to detect nucleic acid of HSV-1 and it should be examined for HSV-1 antibodies. Antibodies to HSV-1 do not appear in the CSF until approximately 8 to 12 days after symptom onset, and increase significantly during the first 2 to 4 weeks of infection. In order to determine if there is an intrathecal synthesis of antibodies against HSV-1, send CSF and serum samples. A serum:CSF ratio of <20:1 is considered diagnostic of HSV-1 infection. Because this infection produces areas of hemorrhagic necrosis, the CSF may contain RBC or xanthochromia. RBC in the CSF may inhibit the PCR, giving a false-negative result.

FIGURE 47.1 T2-weighted MRI shows classical high signal intensity lesion in left temporal lobe in herpes encephalitis. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The EEG often is abnormal, demonstrating periodic sharp-wave complexes from one or both temporal regions. The abnormalities on the EEG arise from one temporal lobe initially but typically spread to the contralateral temporal lobe over a period of 6 to 10 days.

A. Therapeutic approach.

1. Antiviral activity. Acyclovir is the antiviral drug of choice for HSV-1 encephalitis. It is given at a dosage of 10 mg/kg every 8 hours (30 mg/kg/day) IV, each infusion lasting >1 hour, for a period of 3 weeks. IV acyclovir can cause transient renal insufficiency secondary to crystallization of the drug in renal epithelial cells. For this reason, it is recommended that acyclovir be infused slowly over a period of 1 hour and that attention be paid to adequate IV hydration of the patient.

2. Anticonvulsant therapy. Seizure activity, either focal or focal with secondary generalization, occurs in two-thirds of patients with HSV-1 encephalitis. Anticonvulsant therapy is indicated if seizure activity develops, and the following drugs are recommended.

a. Lorazepam at dosages of 0.1 mg/kg for adults and 0.05 mg/kg for children, or diazepam at 5 to 10 mg for adults and 0.2 to 0.3 mg/kg/dose for children.

b. Fosphenytoin at a dose of 18 to 20 mg PE/kg no faster than 150 mg/minute. The daily maintenance dosage of fosphenytoin should be determined by serum levels.

c. Levetiracetam or valproic acid or lacosamide can also be used. All three can be given intravenously.

Therapy for increased ICP. Increased ICP is a common complication of herpes encephalitis and is associated with a poor outcome. Increased ICP should be aggressively managed as outlined in Section A.3 under Bacterial Meningitis.

B. Expected outcome. Among untreated patients with HSV-1 encephalitis, the mortality is higher than 70%, and only 2.5% of patients return to normal function after recovery. Patients treated with acyclovir have a significantly lower mortality of 19%, and 38% of these patients return to normal function.

C. Referrals. Because the clinical diagnosis of herpes encephalitis typically requires interpretation of the neurologic presentation, the EEG, neuroimaging studies, and CSF, the diagnosis of this severe and devastating neurologic illness should be made in consultation with a neurologist.

HERPES ZOSTER (SHINGLES)

A. Therapeutic approach. Oral valacyclovir 1,000 mg three times a day has been found superior to acyclovir in reducing zoster-associated pain. Oral acyclovir 800 mg five times a day and valacyclovir accelerate the rate of cutaneous healing and reduce the severity of acute neuritis and are most beneficial if treatment is initiated within 48 hours. Neither valacyclovir nor acyclovir reduces the incidence or severity of postherpetic neuralgia. For immunosuppressed patients, and for those with zoster ophthalmicus, many experts recommend the use of IV acyclovir. Ganciclovir can be considered an alternative agent for treatment. Corticosteroids have been proposed as adjunctive therapy in immunocompetent patients with varicella-zoster virus encephalitis.

B. Side effects. Oral acyclovir therapy has not been associated with renal dysfunction, but IV acyclovir can cause renal insufficiency. The risk of this complication is decreased by a slow rate of infusion.

C. Prevention. A varicella-zoster vaccine is available to decrease the risk of herpes zoster. Individuals with primary or acquired immunosuppression should not receive the vaccine.

LYME DISEASE

Lyme disease is caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted by the bite of an infected tick. It is endemic in the coastal northeast from Massachusetts to Maryland (particularly in New York), in the upper Midwest in Minnesota and Wisconsin, and on the Pacific coast in California and southern Oregon.

In the majority of patients, initial infection is manifested by the appearance of an annular erythematous cutaneous lesion with central clearing of at least 5 cm in diameter, called erythema migrans. This lesion appears within 3 days to 1 month after a tick bite. Early disseminated Lyme disease is characterized by cardiac conduction abnormalities, arthritis, myalgia, fatigue, fever, meningitis, and cranial and peripheral neuropathy and radiculopathy. The most common neurologic abnormality during early disseminated Lyme disease is meningitis. The clinical features are typical of viral meningitis with symptoms of headache, mild neck stiffness, nausea, vomiting, low-grade fever, and photophobia. These symptoms may be associated with unilateral or bilateral facial nerve palsy or with symptoms of radiculitis (paresthesia and hyperesthesia) with or without focal weakness, transverse myelitis, or mononeuritis multiplex.

The majority of patients with Lyme disease have or have had an erythema migrans lesion. The diagnosis of Lyme disease begins with a serologic test for antibodies against B. burgdorferi. Most laboratories use an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique. False-positive serologic results are a problem with this test for two reasons:

1. Tests can be performed on identical sera in different laboratories with different results. Because these tests are not well standardized, it is important to use a laboratory that is reliable in performing this test. A positive test result may indicate only exposure to B. burgdorferi rather than active infection. Persons who live in high-risk areas may have measurable antibodies without having Lyme disease.

2. False-positive serologic results can occur with rheumatoid arthritis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, infectious mononucleosis, syphilis, tuberculous meningitis, and leptospirosis. When the ELISA is positive, then a Western blot should be obtained. The CSF is generally abnormal in neurologic Lyme disease. The typical spinal fluid abnormalities include lymphocytic pleocytosis (100 to 200 cells per mm3), an elevated protein concentration, and a normal glucose concentration. The CSF should be examined for intrathecal production of anti-B. burgdorferi antibodies, and an antibody index should be calculated. The antibody index is determined as the ratio of (anti-Borrelia IgG in CSF/anti-Borrelia IgG in serum) to (total IgG in CSF/total IgG in serum) and is defined as positive when the result is >1.3 to 1.5. The use of the antibody index to determine that there is an intrathecal production of antibodies is important as antibodies can be passively transferred from serum to CSF giving a false-positive result, and Lyme antibodies may persist in CSF for years.

A. Therapeutic approach.

1. Patients with facial nerve palsy without other neurologic manifestations can be treated with doxycycline 100 mg by mouth twice a day for 14 days. Doxycycline should not be given to pregnant women.

2. Parenteral ceftriaxone is recommended for patients with neurologic complications of Lyme disease, although oral doxycycline may be equally effective in the absence of brain or spinal cord involvement. The adult dosage of ceftriaxone is 2 g/day, which may be given in a single daily dose, and the dosage for children is 75 to 100 mg/kg/day (up to 2 g/day). Treatment is given for at least 2 weeks and should be continued for an additional 2 weeks if the response to treatment is slow or there is severe infection.

3. Alternatives to ceftriaxone are penicillin G and cefotaxime. Penicillin G is administered at an adult dosage of 3 to 4 million units (miU) every 4 hours for 10 to 14 days or at a child dosage of 250,000 U/kg/day in divided doses. The major side effect of penicillin G is hypersensitivity reaction. Cefotaxime is given at dosages of 2 g three times a day for adults and 150 to 200 mg/kg/day (every 6 hours) for children.

B. Expected outcome. The condition of patients with neurologic complications of early disseminated Lyme disease (meningitis, cranial neuropathy, and peripheral neuropathy) should improve clinically within days, although improvement of facial weakness and radicular symptoms can take weeks. Prolonged antimicrobial therapy does not improve symptoms of post-Lyme syndrome and is not recommended.

C. Prevention. The deer tick is the usual vector of Lyme disease in the northeastern and the midwestern United States. Wearing protective clothing can help decrease the risk of infection. Transmission of infection is unlikely if the tick has been attached for <24 hours.

CRYPTOCOCCAL MENINGITIS

The diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis is made when examination of the CSF shows lymphocytic pleocytosis, a decreased glucose concentration, and a positive result of a CSF cryptococcal antigen assay, fungal smear, or culture.

A. Therapeutic approach. The management of cryptococcal meningitis is divided into induction, consolidation, and maintenance (suppressive therapy). Induction therapy includes amphotericin B 0.7 to 1 mg/kg/day in combination with flucytosine 100 mg/kg/day divided into four daily doses for at least 4 weeks. Treatment then is switched to consolidation therapy with fluconazole 400 mg/day for a minimum of 8 weeks. Present guidelines recommend slight modifications for induction and consolidation therapy in HIV-infected patients and in organ transplant recipients. In the treatment of patients with HIV infection, fluconazole 200 mg/day is continued for lifelong suppressive therapy.

B. Side effects. The most important adverse effect of amphotericin B is renal dysfunction, which occurs in 80% of patients. Renal function, hemoglobin concentration, and electrolytes should be monitored closely. Renal toxicity appears to be reduced or prevented by means of careful attention to serum sodium concentration at the time of administration of amphotericin B. If renal insufficiency develops, AmBisome (Fujisawa, Deerfield, IL, USA) 5 mg/kg/day or amphotericin B lipid complex 5 mg/kg/day can be substituted for amphotericin B. Flucytosine is generally well-tolerated; however, bone marrow suppression with anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia can develop. These hematologic abnormalities occur more often when serum concentrations of the drug exceed 100 mgmL; therefore, serum concentrations of flucytosine should be monitored and the peak serum concentration kept well below 100 mg/mL.

NEUROSYPHILIS IN IMMUNOCOMPETENT PATIENTS

In immunocompetent patients, the clinical presentation of neurosyphilis falls into one or more of the following categories: (1) asymptomatic neurosyphilis, (2) meningitis, (3) meningovascular syphilis, (4) dementia paralytica, and (5) tabes dorsalis. The diagnosis of neurosyphilis is based on a reactive serum treponemal test and CSF abnormalities. In neurosyphilis, there is often a mild CSF mononuclear pleocytosis with a mild elevation in the CSF protein concentration or a reactive CSF venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. A positive CSF VDRL test establishes the diagnosis of neurosyphilis. A nonreactive CSF VDRL result does not exclude neurosyphilis. The CSF VDRL test is nonreactive in 30% to 57% of patients with neurosyphilis. A nonreactive CSF fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS) excludes the diagnosis of neurosyphilis in all cases except early syphilis. A reactive CSF FTA-ABS is nonspecific and cannot be used to make a diagnosis of neurosyphilis.

A. Therapeutic approach. The regimen recommended by the CDC for management of neurosyphilis is IV aqueous penicillin G at 18 to 24 miU/day (3 to 4 miU every 4 hours) for 10 to 14 days. An alternative regimen is intramuscular procaine penicillin at 2.4 miU/day and oral probenecid at 500 mg four times a day, both for 10 to 14 days.

B. Expected outcome. The serum VDRL titer should decrease after successful therapy for neurosyphilis. The serum fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test and the microhemagglutination—Treponema pallidum test remains reactive for life. The CSF WBC count should be normal 6 months after therapy is completed. If on reexamination of the CSF, the WBC count remains elevated, repetition of treatment is indicated.

TUBERCULOUS MENINGITIS

A. Clinical presentation. Tuberculous meningitis manifests as either subacute or chronic meningitis, as a slowly progressive dementing illness, or as fulminant meningoencephalitis. The intradermal tuberculin skin test is helpful when the result is positive. Radiographic evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis is found more often in children with tuberculous meningitis than in adults with tuberculous meningitis. The classical abnormalities at CSF examination are decreased glucose concentration, elevated protein concentration, and polymorphonuclear or lymphocytic pleocytosis. The CSF pleocytosis is typically neutrophilic initially, but then becomes mononuclear or lymphocytic within several weeks. Acid-fast bacilli are difficult to find in smears of CSF. Culture of CSF is the standard for diagnosis but is insensitive. Cultures are reported to be positive in 25% to 75% of cases of tuberculous meningitis, requiring 3 to 6 weeks for growth to be detectable. PCR assays that detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis rRNA in CSF have shown good results in clinical trials.

B. Therapeutic approach. Current recommendations for the management of tuberculous meningitis in children and adults include a combination of isoniazid (5 to 10 mg/kg/day up to 300 mg/day), rifampin (10 to 20 mg/kg/day up to 600 mg/day), and pyrazinamide (25 to 35 mg/kg/day up to 2 g/day). If the clinical response is good, pyrazinamide is discontinued after 8 weeks, and isoniazid and rifampin are continued for an additional 10 months. Ethambutol is added, and the course of treatment is extended to 1 to 2 years for immunocompromised patients. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends addition of streptomycin at 20 to 40 mg/kg/day to the foregoing regimen for the first 2 months. Pyridoxine may be administered at a dosage of 25 to 50 mg/day to prevent the peripheral neuropathy that can result from use of isoniazid. Corticosteroid therapy is recommended when clinical deterioration occurs after treatment has begun. Dexamethasone can be administered at a dosage of 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg/day for the 1st week of treatment and followed by oral prednisone.

A diagnosis of neurocysticercosis should be considered when a patient has seizures and neuroimaging evidence of cystic brain lesions. Cysticercosis is acquired by ingesting the eggs of the Taenia solium tapeworm shed in human feces.

A. Principal forms. The lesions of neurocysticercosis can be found in the brain parenchyma, the ventricles, the subarachnoid space, or in the basilar cisterns (racemose forms). In the parenchymal form, single or multiple cysts are found in the gray matter in the cerebrum and cerebellum. Cysticercal intraparenchymal cysts evolve through four stages with different appearances on neuroimaging. In the vesicular stage, the cyst contains a living larva. The scolex is often seen on CT and MRI. In the colloidal stage, the larva degenerates and on neuroimaging, the lesion is surrounded by edema. In the granulo-nodular stage, the membrane of the cyst thickens. In the final stage, the lesion is a calcified lesion. The most common clinical manifestation of parenchymal neurocysticercosis is new-onset seizure activity. In the ventricular form, single or multiple cysts are adherent to the ventricular wall or free in the CSF. Cysts are most common in the area of the fourth ventricle. In subarachnoid neurocysticercosis, cysts are found in the subarachnoid space or fixed under the pia and burrowed into the cortex. In the racemose form, cysts grow, often in clusters, in the basilar cisterns and obstruct the flow of CSF. Hydrocephalus and cysticercotic encephalitis, a severe form of neurocysticercosis due to intense inflammation around cysticerci and cerebral edema, are the most common cause of increased ICP.

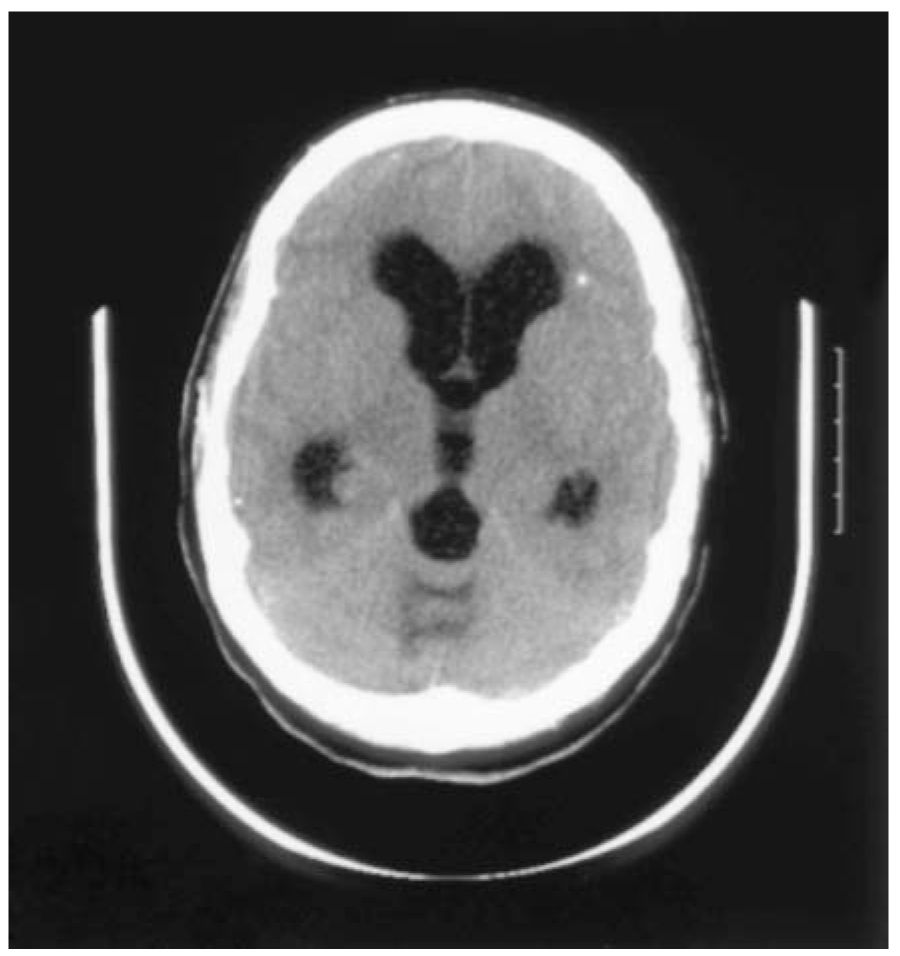

B. Diagnosis. The diagnosis of neurocysticercosis depends on clinical features and evidence of cystic lesions demonstrating the scolex at CT or MRI, or other neuroimaging abnormalities (ring enhancing cystic lesions and intraparenchymal calcifications) (Fig. 47.2) suggestive of neurocysticercosis. Serum may be sent for enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot assay. Biopsy for histologic demonstration of the parasite is rarely done.

FIGURE 47.2 CT scan shows parenchymal brain calcification and hydrocephalus due to neurocysticercosis. CT, computed tomography.

C. Therapeutic approach.

1. Cysticidal therapy consists of praziquantel at a dose of 50 mg/kg/day for 15 days, or praziquantel 100 mg/kg in three divided doses at 2-hour intervals (single day course) or albendazole at a dosage of 15 mg/kg/day for 8 days.

2. Corticosteroids. Cysticidal therapy frequently causes an inflammatory response with an increase in CSF protein concentration and CSF pleocytosis. This may result in an exacerbation of signs and symptoms. The incidence of an inflammatory response is reduced by the concomitant use of corticosteroids, and their use is recommended both before and during treatment with anticysticidal therapy. Plasma levels of albendazole are increased by dexamethasone; plasma levels of praziquantel are decreased by dexamethasone therapy. This should be taken into consideration when corticosteroid therapy is used to decrease the headaches and vomiting induced by the destruction of parasites in cysticidal therapy. Dexamethasone 24 to 32 mg/day is recommended for patients with subarachnoid cysts, encephalitis, angiitis, or arachnoiditis.

3. Side effects. Phenytoin and carbamazepine decrease serum praziquantel levels due to their induction of the cytochrome P-450 liver enzyme system. If one of these anticonvulsants is used with praziquantel, it is recommended that oral cimetidine be added at a dosage of 800 mg twice a day. Cimetidine inhibits the cytochrome P-450 enzyme system, and in this way increases serum levels of praziquantel.

4. Surgical therapy. Intraventricular cysts necessitate surgical therapy, and when they obstruct the flow of CSF with resulting hydrocephalus, an intraventricular shunting device is indicated.

D. Expected outcome. The prognosis of patients with parenchymal neurocysticercosis is very good with cysticidal therapy. Cystic lesions should disappear within 3 months of treatment. The mortality is higher among patients with increased ICP, hydrocephalus, or the racemose form of the disease.

E. Prevention. Humans can acquire cysticercosis by eating food handled and contaminated by T. solium tapeworm carriers. Persons at high risk of tapeworm infestation who are employed as food handlers should be screened for intestinal parasites. Improved sanitation can decrease the incidence of cysticercosis from contaminated food or drinking water.

Key Points

• Bacterial meningitis is a neurologic emergency, and initial treatment is empiric until a specific organism is identified. Obtain blood cultures and begin antimicrobial therapy prior to neuroimaging or CSF analysis.

• Empiric therapy for community-acquired meningitis in infants, children, and adults (15 to 50 years of age) is the combination of a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin plus vancomycin.

• Add ampicillin to empiric antimicrobial therapy (a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin and vancomycin) in adults 50 years of age or older.

• Every patient with fever and headache, in whom herpes simplex virus-1 encephalitis is a possibility, should be treated with acyclovir 10 mg/kg/every 8 hours as soon as possible to decrease mortality and morbidity.

• The CSF HSV-1 PCR may be negative in the first 72 hours of symptoms of HSV encephalitis.

• Magnetic resonance fluid-attenuated inverse recovery (FLAIR) and diffusion-weighted sequences demonstrate an abnormal lesion of increased signal intensity in the temporal lobe in 90% of adult patients with herpes simplex virus encephalitis 48 hours after symptom onset.

• Neurologic Lyme disease may manifest as a seventh nerve or bilateral seventh nerve palsies (cranial nerves III, IV, and VI may also be involved), a radiculitis, a mononeuritis multiplex, and/or a lymphocytic meningitis.

• A positive CSF VDRL—treat for neurosyphilis.

• Negative CSF FTA-ABS, negative CSF VDRL, no CSF pleocytosis, normal protein concentration—no treatment for neurosyphilis is required.

• Negative CSF VDRL, increased white blood cell count, and/or protein concentration—treat for neurosyphilis.

• In neurocysticercosis, only cysts in the vesicular and colloidal stages contain live larva and are amendable to anticysticercal treatment. On neuroimaging, the scolex can often be seen in a cyst in the vesicular stage. As the larva degenerates, the cyst enters the colloidal stage and on neuroimaging, edema surrounds the lesion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree