16 Child and adolescent psychiatry

Child psychiatric disorder

Definition and classification

The ICD-10 classification of ‘Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence’ (F90–98) is shown in Table 16.1. In general, if the criteria for one of the other ‘adult’ disorders (such as depression) are met, then such a diagnosis should be made rather than a ‘childhood-onset’ diagnosis. Recognition of different dimensions of childhood functioning has led the WHO to develop a multiaxial framework for the diagnosis of child psychiatric disorder (Table 16.2). DSM-IV-TR disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood or adolescence are outlined in Table 16.3.

Table 16.1 ICD-10 classification: F90–F98 Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence

| F90 | Hyperkinetic disorders |

| F90.0 Disturbance of activity and attention | |

| F90.1 Hyperkinetic conduct disorder | |

| F90.8 Other hyperkinetic disorders | |

| F90.9 Hyperkinetic disorder, unspecified | |

| F91 | Conduct disorders |

| F91.0 Conduct disorder confined to the family context | |

| F91.1 Unsocialized conduct disorder | |

| F91.2 Socialized conduct disorder | |

| F91.3 Oppositional defiant disorder | |

| F91.8 Other conduct disorders | |

| F91.9 Conduct disorder, unspecified | |

| F92 | Mixed disorders of conduct and emotions |

| F92.0 Depressive conduct disorder | |

| F92.8 Other mixed disorders of conduct and emotions | |

| F92.9 Mixed disorder of conduct and emotions, unspecified | |

| F93 | Emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood |

| F93.0 Separation anxiety disorder of childhood | |

| F93.1 Phobic anxiety disorder of childhood | |

| F93.2 Social anxiety disorder of childhood | |

| F93.3 Sibling rivalry disorder | |

| F93.8 Other childhood emotional disorders | |

| F93.9 Childhood emotional disorder, unspecified | |

| F94 | Disorders of social functioning with onset specific to childhood and adolescence |

| F94.0 Elective mutism | |

| F94.1 Reactive attachment disorder of childhood | |

| F94.2 Disinhibited attachment disorder of childhood | |

| F94.8 Other childhood disorders of social functioning | |

| F94.9 Childhood disorders of social functioning, unspecified | |

| F95 | Tic disorders |

| F95.0 Transient tic disorder | |

| F95.1 Chronic motor or vocal tic disorder | |

| F95.2 Combined vocal and multiple motor tic disorder (Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome) | |

| F95.8 Other tic disorders | |

| F95.9 Tic disorder, unspecified | |

| F98 | Other behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence |

| F98.0 Non-organic enuresis | |

| F98.1 Non-organic encopresis | |

| F98.2 Feeding disorder of infancy and childhood | |

| F98.3 Pica of infancy and childhood | |

| F98.4 Stereotyped movement disorders | |

| F98.5 Stuttering (stammering) | |

| F98.6 Cluttering | |

| F98.8 Other specified behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | |

| F98.9 Unspecified behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence |

Table 16.2 ICD-10 Multiaxial framework

| Axis One | Clinical psychiatric syndromes |

| Axis Two | Specific disorders of psychological development |

| Axis Three | Intellectual level |

| Axis Four | Medical conditions |

| Axis Five | Associated abnormal psychosocial situation |

Table 16.3 DSM-IV-TR disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood or adolescence

| Learning disorders | |

| 315.0 | Reading disorder |

| 315.1 | Mathematics disorder |

| 315.2 | Disorder of written expression |

| 315.9 | Learning disorder NOS |

| Motor skills disorder | |

| 315.4 | Developmental coordination disorder |

| Communication disorders | |

| 315.31 | Expressive language disorder |

| 315.32 | Mixed receptive–expressive language disorder |

| 315.39 | Phonological disorder |

| 307.0 | Stuttering |

| 307.9 | Communication disorder NOS |

| Pervasive developmental disorders | |

| 299.00 | Autistic disorder |

| 299.80 | Rett’s disorder |

| 299.10 | Childhood disintegrative disorder |

| 299.80 | Asperger’s disorder |

| 299.80 | Pervasive developmental disorder NOS |

| Attention-deficit and disruptive behavioural disorders | |

| 314.xx | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| .01 | Combined type |

| .00 | Predominantly inattentive type |

| .01 | Predominantly hyperactive–impulsive type |

| 314.9 | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder NOS |

| 312.xx | Conduct disorder |

| .81 | Childhood-onset type |

| .82 | Adolescent-onset type |

| .89 | Unspecified onset |

| 313.81 | Oppositional defiant disorder |

| 312.9 | Disruptive behaviour disorder NOS |

| Feeding and eating disorders of infancy or early childhood | |

| 307.52 | Pica |

| 307.53 | Rumination disorder |

| 307.59 | Feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood |

| Tic disorders | |

| 307.23 | Tourette’s disorder |

| 307.22 | Chronic motor or vocal tic disorder |

| 307.21 | Transient tic disorder (115) (Specify if Single episode/recurrent) |

| 307.20 | Tic disorder NOS (116) |

| Elimination disorders | |

| —.— | Encopresis |

| 787.6 | With constipation and overflow incontinence |

| 307.7 | Without constipation and overflow incontinence |

| 307.6 | Enuresis (not due to a general medical condition) (Specify type: Noctumal only/diurnal only/nocturnal and diurnal) |

| Other disorders of infancy, childhood, or adolescence | |

| 309.21 | Separation anxiety disorder (Specify if Early onset) |

| 313.23 | Selective mutism |

| 313.89 | Reactive attachment disorder of infancy or early childhood (Specify type: Inhibited type/disinhibited type) |

| 307.3 | Stereotypic movement disorder (Specify if With self-injurious behaviour) |

| 313.9 | Disorder of infancy, childhood, or adolescence NOS (134) |

NOS, not otherwise specified

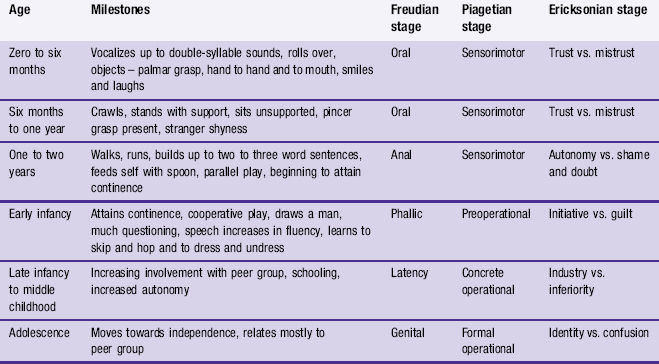

In child and adolescent psychiatry it is essential to have a clear knowledge of the normal development of all aspects of behavioural and psychological functioning. Detailed accounts of childhood development may be found in paediatric texts and developmental psychology books. Table 16.4 shows an outline of various developmental milestones, and includes references to various different theories of psychological development. It must be noted that these theories are ways of conceptualizing development, each designed to explain and predict, with implications for management and treatment. They are not the literal truth and are by no means mutually exclusive. Only brief outlines of the theories can be given here.

Some aspects of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory are described in Chapter 4. Erikson saw development as a series of stages or psychosocial crises that must be overcome to make proper relationships at each stage in life. The stages relate to a widening and narrowing social world (see Chapter 2).

Aetiology

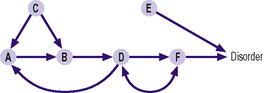

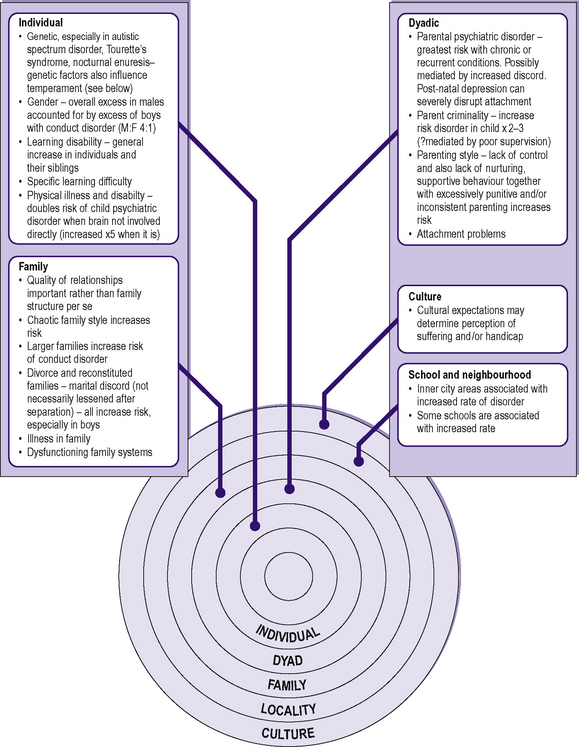

In child and adolescent psychiatry multifactorial aetiology is the rule. This is not simply in the sense of many factors contributing to a given predicament, but in the interaction of such factors at all levels of a child’s or adolescent’s functioning, either adding to or subtracting from the risk (Figure 16.1). Such interactions may be circular rather than simply linear. There is also a variation in effect, according to the development level of the child, the family’s stage in the life cycle and the particular resilience and vulnerability factors operating in an individual situation. Aetiological factors according to biopsychosocial level are summarized in Figure 16.2.

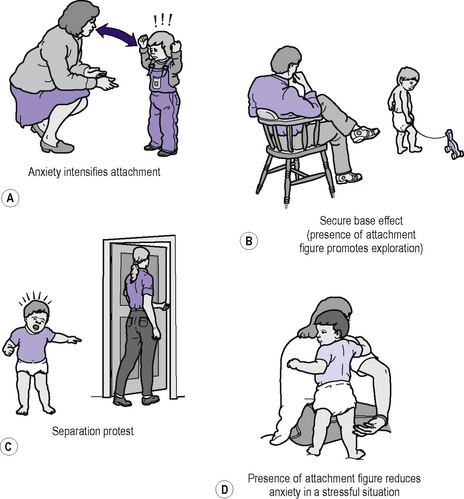

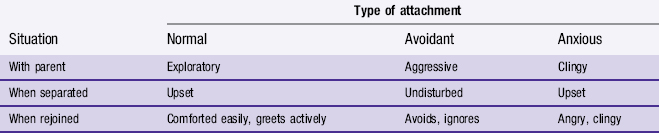

‘Attachment’ is an important concept in psychiatry as it encompasses both early social relationships and subsequent patterns of interaction with others. It must be emphasized that attachment is a relationship variable, not a personal characteristic. Quality of attachment to one carer does not predict type of attachment to another. The cardinal features of attachment are shown in Figure 16.3. The quality of attachments has been explored, most notably by Ainsworth, who devised an experimental procedure (the strange situation procedure) in which a child goes through a series of short separations and reunions with both carer and a stranger in an unfamiliar room. Responses were classified to produce three ‘types’ of attachment (Table 16.5).

Table 16.5 Attachment: Ainsworth’s strange situation procedure (showing child’s behaviour seen in different situations)

All behaviour arises in the context of relationships. Taking a family perspective raises interactional issues that may be aetiologically important in a given case. Minuchin and others have described particular features of families with a child with a ‘psychosomatic’ complaint (enmeshment, rigidity, inappropriate parent–child alliances). Most papers have been descriptive of the therapeutic approaches of a particular ‘school of family therapy’, although there is considerable overlap between these. A linear view of causality is generally not helpful in considering families and the wider system: a circular model is preferable. Changes in one part of the system will require other parts to adjust to take account of this, or alternatively act in such a way to maintain the status quo. An example would be where a particular child is taking all its parent’s attention by naughty behaviour: this relieves the pressure on the siblings, who may act to ‘wind up’ the identified child if their naughtiness then appears to be reduced. There are many similar features of family systems that may trigger, maintain or predetermine a presenting complex of symptoms. Table 16.6 summarizes the areas that must be considered, though research is difficult and scanty in determining the relative importance of these different variables.

Table 16.6 Elements of family functioning

| Interactional patterns | Who is in the family? |

| Biological and marital relationships | |

| Communication patterns | |

| Hierarchical structure | |

| Pattern of alliances | |

| Clarity or otherwise of intergenerational boundary | |

| Control or authority systems | |

| Relationship with the outside world | |

| Sociocultural context | Economic status |

| Social mobility | |

| Migration status | |

| Location of the family on the life cycle | Number of transitions |

| Requirements for adaptation | |

| Intergenerational structure | Experiences of parents as children |

| Influences of grandparents and extended family | |

| Significance of symptom for the family | Symbolic meaning? |

| Implications? | |

| Factors rewarding or inhibiting symptom | |

| Family problem-solving skills | Family style |

| Previous experience |

(Derived from Dare C 1985 Family therapy. In: Rutter M, Hersov L (eds) Child and adolescent psychiatry: modern approaches. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford.)

Some characteristics of schools, regardless of catchment area, influence the level of child psychiatric disorder (Table 16.7). Epidemiological studies have further emphasized that there is a discontinuity between a child’s presentation in school and at home. Children spend a large part of their formative years in school. Poor relationships between home and school can be significant in maintaining an undesirable symptom complex.

Table 16.7 Features of a school associated with a lower level of child psychiatric disorder (independent of catchment population)

Management

Assessment

At the first assessment appointment a considerable amount of information is required to obtain a sufficiently wide view of the presenting problem (Table 16.8). Studies suggest that an active probing style produces more detailed information than does a ‘free-form’ dialogue, but it is important to start with open questioning before proceeding to more specific queries.

Table 16.8 Information to be amassed in a child psychiatric interview

| Source and nature of referral |

| Description of presenting complaints |

| Description of child’s current general functioning |

| Personal/developmental history |

| Family history |

• Personal and social histories of both parents especially:

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|