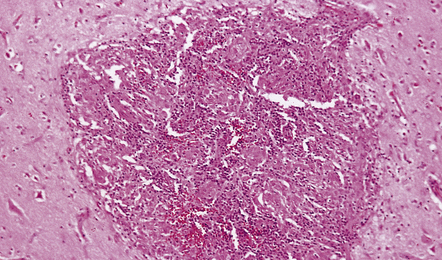

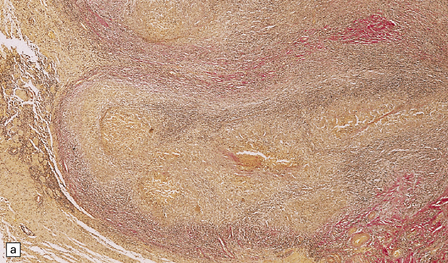

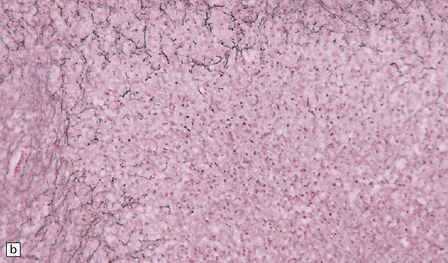

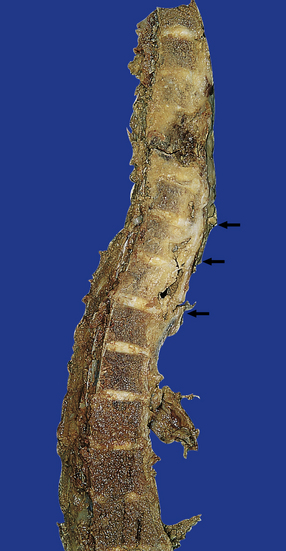

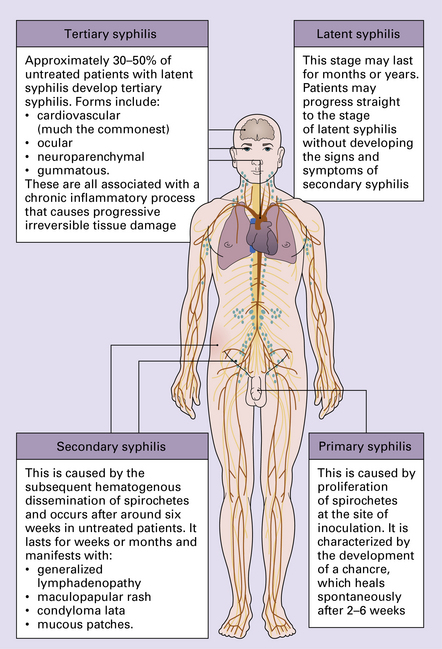

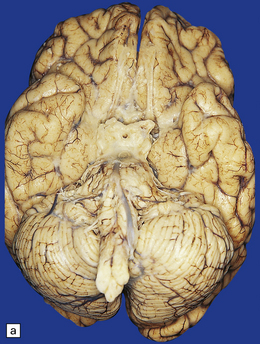

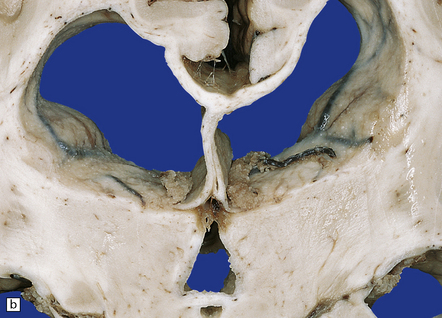

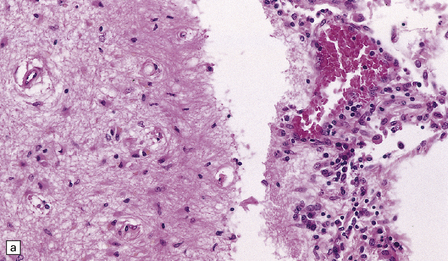

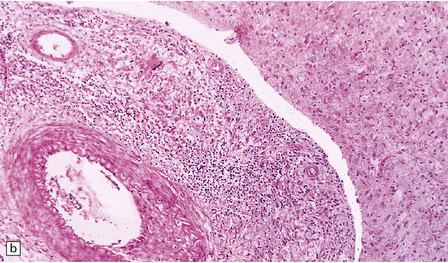

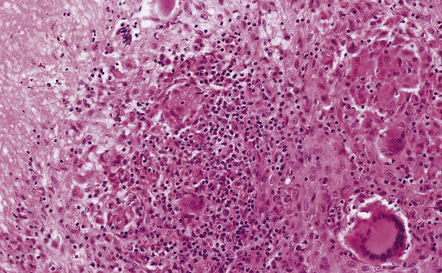

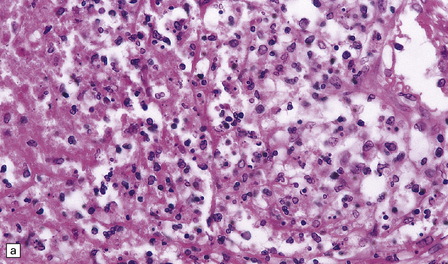

16 Tuberculous meningitis is characterized by a gelatinous subarachnoid exudate. This may appear slightly nodular and is usually thickest in the sylvian fissures, over the base of the brain (Fig. 16.1a), and around the spinal cord. Sectioning of the brain usually reveals a similar exudate within the choroid plexus and lining the ventricles. Tubercles may be visible in the meninges, usually adjacent to sulcal veins, and in the ventricular lining (Fig. 16.1b). Small superficial tuberculomas are quite common (Fig. 16.2) and may be associated with an overlying meningeal exudate. Large tuberculomas occasionally occur, but are rare in patients with meningitis. 16.1 Tuberculous meningitis. The meningeal and ventricular exudate contains lymphocytes, macrophages, and sparse plasma cells, admixed with necrotic material and fibrin (Fig. 16.3a). There may be accumulations of epithelioid cells and fibroblasts, multinucleated giant cells, and well-defined tuberculous granulomas (Figs 16.2, 16.3, 16.4) with central caseous necrosis. 16.3 Histology of tuberculous meningitis. 16.4 Part of a caseating meningeal granuloma in tuberculous meningitis. 16.5 Tuberculous meningitis in an immunosuppressed patient. The inflammation extends into the subpial and periventricular brain tissue, which shows reactive astrocytosis (Fig. 16.3a) and microglial proliferation. This may be associated with degeneration of white matter adjacent to the ventricles and in the spinal cord. The inflammatory cells tend to infiltrate through the adventitia, into the media and even the intima, of blood vessels within the exudate (Figs 16.3b, 16.6). Thrombosis occurs in some blood vessels. In others, the inflammation provokes a subintimal intimal fibroblastic reaction that narrows and can occlude the lumen (Figs 16.3b, 16.7). Infarcts are therefore common (Fig. 16.8), particularly in the superficial cortex and, due to the involvement of perforating branches of the middle cerebral artery, in the basal ganglia. 16.6 Mild tuberculous endarteritis. 16.7 Tuberculous endarteritis. 16.8 Acute infarction of superficial brain parenchyma in tuberculous meningitis. Histology reveals solitary or confluent tuberculous granulomas with central caseous necrosis surrounded by lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, Langhans’-type multinucleated giant cells, and an outer zone of collagen, fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and macrophages (Fig. 16.9). Older lesions may calcify. The adjacent parenchyma is usually markedly gliotic. There is usually extensive destruction, which may be associated with collapse of the affected vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs. This is associated with variable protrusion of gray multinodular granulomatous tissue into the epidural space (Fig. 16.10). The epidural mass shows typical granulomatous tuberculous inflammation with caseation. Changes in the spinal cord reflect a combination of focal compression by epidural inflammatory tissue or vertebral kyphosis, ischemia (see Chapter 9), and secondary long tract degeneration. Compression of the anterior spinal artery may produce a typical ‘watershed’ infarct (see Chapter 9) involving the upper and middle parts of the thoracic cord. The different types of CNS involvement in syphilis have been classified as:

Chronic bacterial infections and neurosarcoidosis

TUBERCULOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

(a) Thick pale yellow exudate over base of brain, particularly around the optic chiasm. (b) Nodular thickening of the lining of the lateral ventricles.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

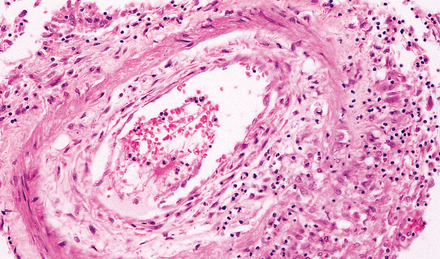

(a) There is a meningeal exudate of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibrin. The superficial cortex (at left) is densely gliotic. (b) Meningeal artery surrounded by lymphocytes, macrophages, and an occasional multinucleated giant cell. There is mild endarteritis, with proliferation of subintimal fibroblasts.

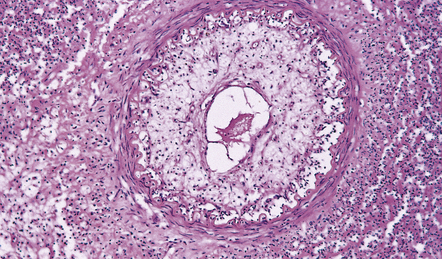

There is a characteristic infiltrate of lymphocytes, epithelioid macrophages, and Langhans’-type multinucleated giant cells.

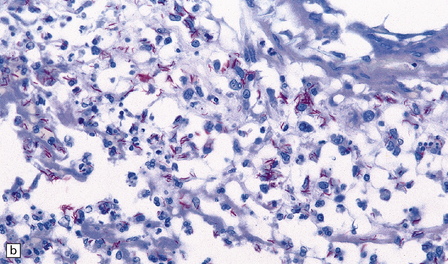

Mycobacteria may be readily demonstrable or very sparse. Silver impregnation reveals a loss of reticulin in the caseous material (see Fig. 16.9 b). In immunosuppressed patients the mycobacteria are usually numerous and the inflammation less granulomatous and usually lacking multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 16.5). Parenchymal arteritis and infarcts have been reported as frequent findings in patients with AIDS.

(a) Inflammation in the leptomeninges of a patient with AIDS. Note the absence of a typical granulomatous tissue reaction. (b) Numerous acid-fast bacilli in AIDS-associated tuberculous meningitis.

Extension of granulomatous inflammation through the adventitia and media of a meningeal artery.

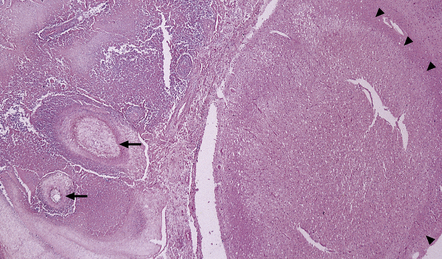

Narrowing of the lumen of an inflamed meningeal artery by accumulation of chronic inflammatory cells and proliferation of intimal connective tissue.

Several arteries in the overlying leptomeninges are occluded or severely stenosed by intimal fibroplasias (arrows). The zone of acute infarction is delineated by arrowheads.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

SPINAL EPIDURAL TUBERCULOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

SYPHILIS

Asymptomatic CNS involvement, associated with CSF pleocytosis and increased immunoglobulin concentration, and positive CSF syphilis serology.

Asymptomatic CNS involvement, associated with CSF pleocytosis and increased immunoglobulin concentration, and positive CSF syphilis serology.

Parenchymatous neurosyphilis (general paresis and tabes dorsalis).

Parenchymatous neurosyphilis (general paresis and tabes dorsalis).

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chronic bacterial infections and neurosarcoidosis