Fig. 7.1

Developmental framework and validation of the C-EOS: validation model. Phases 1A, 1B, and 1C are completed. *The remaining phases will be described in future studies (Reprinted from Vitale [18]. With permission from Rockwater, Inc.)

7.2.1 Phase 1A: Content Library

A thorough literature review of existing scoliosis classifications identified nine unique systems [15–17, 19–23]. From them, a list of factors important to the management of spinal deformity was compiled and narrowed by the panel through structured discussions and qualitative interviews. A final library of 13 potential EOS variables was assembled (Table 7.1) for evaluation during Phase 1B.

Table 7.1

Variable content validity rankings: participant ratings of the 13 proposed variables included on the primary survey on a 3-point Likert scale used to assess content validity as proposed by Lawshe [24]

Variable | Not useful | Useful | Essential | CVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cobb angle | 0 | 1 | 13 | 0.86 |

Etiology | 0 | 3 | 11 | 0.57 |

Kyphosis | 0 | 3 | 11 | 0.57 |

Age | 5 | 0 | 9 | 0.29 |

Progression | 3 | 5 | 6 | −0.14 |

Curve flexibility | 3 | 6 | 5 | −0.29 |

Chest wall abnormalities | 2 | 8 | 4 | −0.43 |

Other co-morbidities | 3 | 8 | 3 | −0.57 |

Pulmonary function | 3 | 8 | 3 | −0.57 |

Nutritional status | 5 | 7 | 2 | −0.71 |

Ambulatory ability | 2 | 11 | 1 | −0.86 |

Mental function | 9 | 5 | 0 | −1.00 |

Bone quality | 10 | 4 | 0 | −1.00 |

7.2.2 Phase 1B: Nominal Group Technique

The nominal group technique is a well-established method of building consensus among professionals in a given area of study. Consisting of iterative rounds of item-rating and group discussion, it has been successfully implemented in multiple medical fields to establish treatment indications and guidelines [24–29]. Using the library generated in Phase 1A, participants rated variables on a 3-point Likert scale: not useful, useful, and essential. These results were used to calculate the content validity ratio (CVR), a well-described measure of how essential an item is to the topic under study [30], for each variable to determine group-wide importance.

Using a minimum CVR of 0.51 to satisfy the 5 % level (i.e., exceed chance expectation) [30], the variables with significant CVRs on the primary survey were major curve angle (0.86), etiology (0.57), and kyphosis (0.57) (see Table 7.1). Although age had the fourth highest-ranking CVR (0.29), it did not meet the CVR significance threshold. Further discussions determined that because age carries import implications regarding patient management and outcomes, it would still be included as a continuous classification prefix. Curve progression and flexibility also did not meet the content validity cut-off point but were later deemed important to decision-making nonetheless. They were instead considered as optional modifiers to be included at a provider’s discretion. Curve flexibility was later discarded.

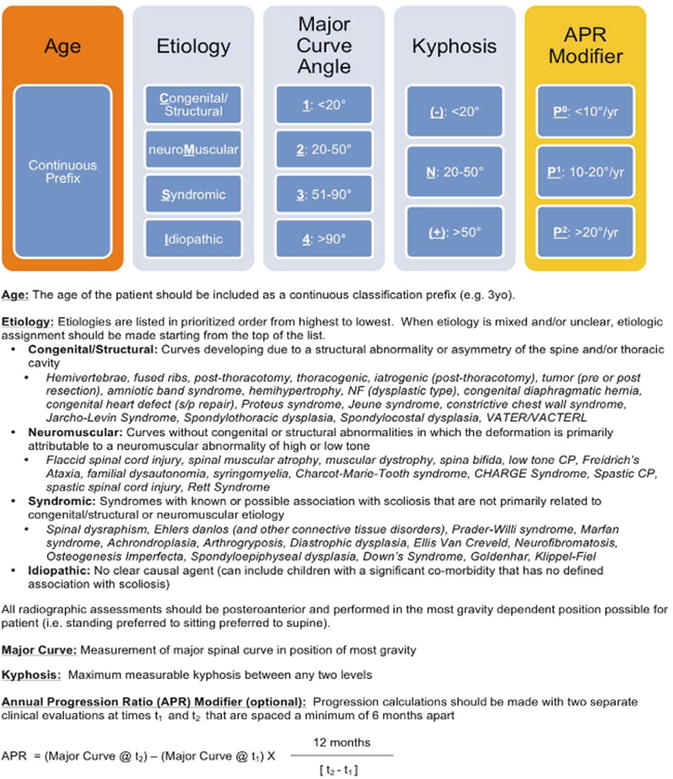

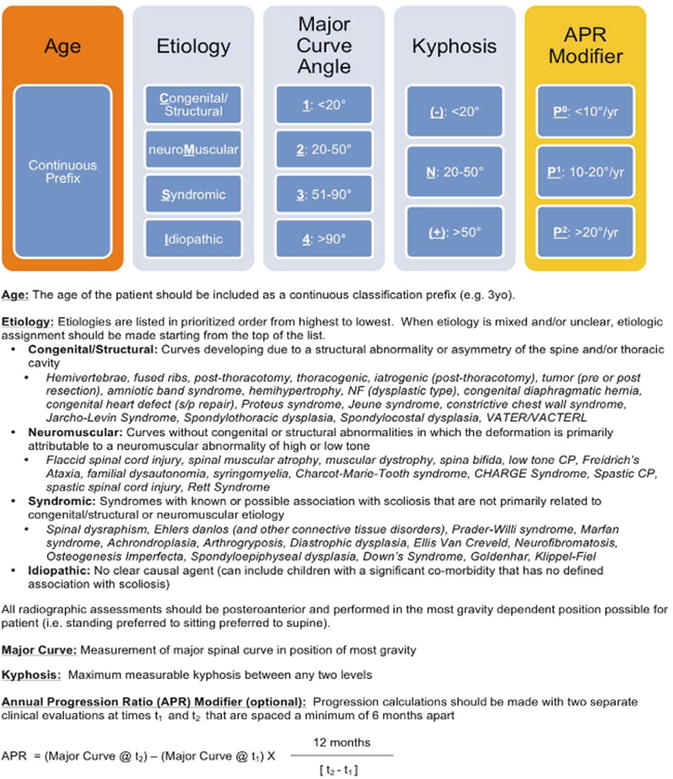

The preliminary classification underwent multiple rounds of modifications based on e-mail discussions, in-person meetings, and a secondary survey. Participants reconvened and reached consensus regarding final modifications, variable subgroups, and cut-points. The Classification of Early-Onset Scoliosis (C-EOS), consisting of a continuous prefix (age), three core variables (etiology, major curve angle, and kyphosis), and an optional modifier (curve progression), is illustrated in Fig. 7.2. A case example of the C-EOS in practice is shown in Fig. 7.3.

Fig. 7.2

The Classification of Early-Onset Scoliosis (C-EOS) (Reprinted from Vitale [18]. With permission from Rockwater, Inc.)

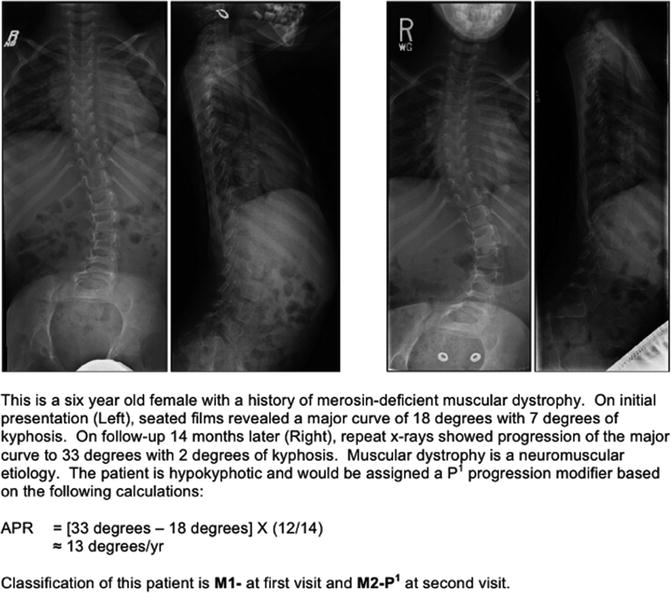

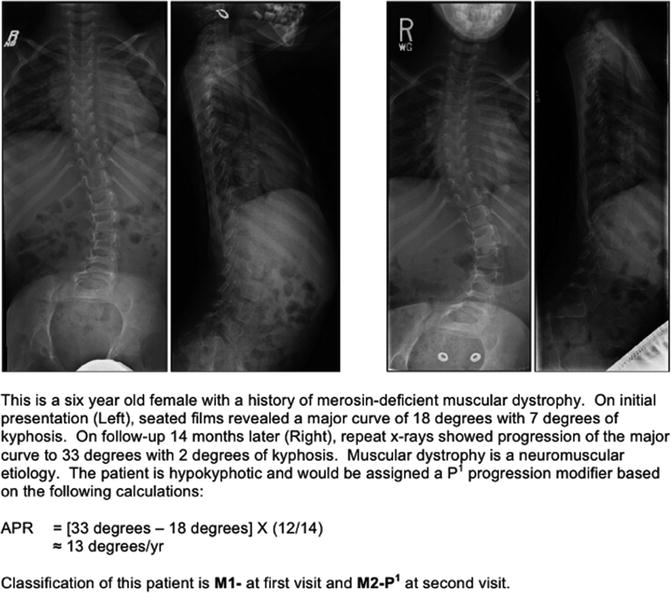

Fig. 7.3

Sample case: use of the C-EOS in a sample case presentation (Reprinted from Vitale [18]. With permission from Rockwater, Inc.)

7.2.2.1 Age

There is no question that patient age at the time of evaluation carries important implications regarding treatment decision-making and prognosis. Several different age-based groupings were proposed during the iterative consensus-based process; however, agreement for any single system was lacking. It was clear that the perceived importance of where to draw the “line in the sand” varied greatly among participants. Because of this, the group decided to include age in the C-EOS as a continuous prefix. Future efforts to provide meaningful subgroup structuring for the age prefix are still encouraged.

7.2.2.2 Etiology

The impact of etiology on the natural history and management of EOS cannot be understated. The severity of scoliosis and response to treatment is often determined by factors very specific to a particular diagnosis [6, 31–34]. For example, multiple studies have shown derotational casting to be a potentially curative intervention for infantile idiopathic scoliosis, while its utility for non-idiopaths remains in question [35–38].

When finalizing etiologic subgroups, priority was given to pairing those etiologies which are managed most similarly. To improve clarity in cases of unclear or mixed etiology, three final modifications were made. First, neuromuscular patients with abnormally high or low tone were collapsed into a single group to remove any ambiguity. Second, a number of commonly encountered conditions were assigned and catalogued as belonging to a particular etiology (see Fig. 7.2). Third, in cases of mixed etiology, an order of priority was assigned which, from highest to lowest, is congenital/structural (C), neuromuscular (M), syndromic (S), and idiopathic (I). Patients with multiple disease states are then assigned to the subgroup of highest priority.

7.2.2.3 Major Curve Angle

Subgroup cut-points were initially based on previously described ranges of major curve angles for guiding the management of scoliosis [12]. Modifications were made after group discussion during the nominal group technique. Consensus was reached for the following major curve subgroupings: Group 1 as <20°, Group 2 ranging from 20° to 50°, Group 3 from 51° to 90°, and Group 4 as >90°. Future studies utilizing the C-EOS will test the hypothesis that these subgroups will correlate with outcomes of various treatment strategies.

7.2.2.4 Kyphosis

The C-EOS defines kyphosis as the highest measurable sagittal Cobb angle between any two levels. This is in contrast to the classification system for AIS developed by Lenke et al. [16] and reflects the observation that kyphosis often extends into the lumbar spine in patients with EOS. Normative data from the available literature suggest that the pediatric measures of kyphosis are different from adults’ and generally increase with age [39]. With this in mind, the normokyphotic (N) range was selected to be 20–50° [40], with hypokyphosis (−) and hyperkyphosis (+) falling on either side. Of note, hyperkyphosis has recently been studied as a metric of operative importance in EOS patients undergoing growing-rod surgery [41]. Ongoing validation studies will investigate the impact of kyphosis as it fits in the C-EOS schema and the effect on treatment outcomes.

Curve Flexibility

Despite the importance of curve flexibility in clinical decision-making, there remains considerable variation in the flexibility imaging techniques between institutions. At many centers, flexibility imaging is not routinely performed throughout the course of care in children with EOS. In addition, most imaging is both effort and gravity-dependent, and depending on the child’s physical and cognitive involvement, he or she may be unable to achieve a proper flexibility assessment. For these reasons and other barriers to widespread and reliable calculation, curve flexibility was ultimately excluded from the C-EOS.

7.2.2.5 Curve Progression

The clinical significance of the velocity of curve progression is well documented in the literature [3, 6, 35, 42]. Among patients with congenital EOS, McMaster et al. [31] determined that the rate of curve progression depends on anomaly type and location and that the highest risk occurs during periods of rapid growth (e.g., the first 2–3 years of life, puberty). Rodillo et al. [33] showed that rates of progression in children with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) ranged from 5° to 15°/year, depending on disease type, relation to puberty, and ambulatory status (e.g., increased rate after loss of ambulation). In young children with idiopathic scoliosis, Scott et al. demonstrated that although a curve can be stable for years, when it starts to progress, it will do so in a fairly constant fashion. They believed that the end result depends primarily on the ages at which progression begins and growth finishes and that any variation from a steady rate of 5°/year was likely due to flexibility or measurement error [43].

Unfortunately, the extensive variability among providers in the reporting of curve progression presents an obstacle to reliable assessment. That is, the meaning of “the curve has progressed 15° since the last visit” cannot be scaled unless the duration of time between the visits is duly reported. To control for any potential inconsistency, a simplified annual progression ratio was developed to standardize the calculation of curve progression (see Fig. 7.2). A minimum of 6 months of follow-up between points is required for inclusion. Future efforts will aim to characterize definable patterns in the rates and timing of change in the annual progression ratio, utilize the C-EOS to identify children with inherently higher risk of accelerated decompensation, and examine the rate of progression as it contributes to the C-EOS in predicting treatment outcomes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree