40 Combined Cranioendoscopic Approach

Piero Nicolai, Arkadi Yakirevitch, Andrea Bolzoni Villaret, Paolo Battaglia, Davide Locatelli, and Paolo Castelnuovo

Introduction

Introduction

During the past 40 years, anterior craniofacial resection followed by radiotherapy has been considered the gold standard in the treatment of malignancies of the sinonasal tract encroaching upon the anterior skull base. In 1997, Yuen et al1 pioneered the so-called cranionasal resection for treatment of malignant sinonasal tumors involving the anterior skull base, combining traditional frontal craniotomy with a transnasal endoscopic approach. Our group began to use this technique, called the cranioendoscopic approach (CEA), in 1996, and our preliminary results have been published.2,3 The main advantage offered by this combined surgical technique over standard craniofacial resection is the multiperspective visualization afforded by straight and angled rigid telescopes. Tumor margins can be determined with greater confidence and magnification at the level of the sphenoid sinus, the medial maxillary wall, the pterygopalatine fossa, and especially at the sinonasal–orbital interface when orbital clearance is not needed. The technique also avoids facial incisions with additional pain, swelling, scar, and deformity.

Indications

Indications

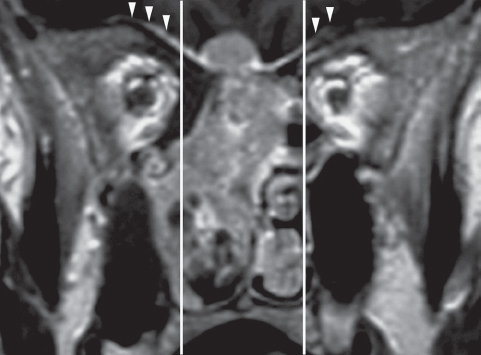

The CEA is recommended for removal of sinonasal lesions with endonasal and endocranial extension requiring a dural resection extending over the orbital roof(s) (Fig. 40.1) or with extensive brain contact/involvement (Fig. 40.2).

Contraindications

Contraindications

The contraindications for CEA are summarized in Table 40.1. It is noteworthy that Batra et al4 consider the need for orbital clearance, lateral tumor extension with invasion of the pterygopalatine space, and infratemporal fossa to be relative contraindications. In our experience, these situations cannot be safely managed with a purely endoscopic approach.

Fig. 40.1 Enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), coronal section demonstrates a right nasoethmoidal lesion (adenocarcinoma) with an “hourglass” intradural extension through the ethmoidal roof. Diffuse enhancement of the dural layer (arrowheads) over the orbital roof is suspicious for neoplastic spread. The vertical lines limit the area of the dura safely resectable by a pure endoscopic approach.

Fig. 40.2 Enhanced T1-weighted MRI, sagittal section demonstrates an ethmoidal squamous cell carcinoma with significant intracranial extension involving the brain parenchyma (arrowheads).

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnostic Workup

The preoperative diagnostic workup includes physical examination with a special focus on neurologic and ophthalmologic assessment; endoscopic examination with preoperative biopsies is always performed after the imaging studies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium enhancement is preferred to computed tomography (CT) for its better definition in evaluating tumor spread in soft tissues, particularly at the interface of the orbital content and the brain. When required (in the presence of nodal disease or in a case of aggressive lesions such as malignant melanoma and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma), distant metastatic dissemination of the disease is excluded by total-body positron emission tomography (PET)-CT. Moreover, a 6-foot anterior-posterior x-ray of the skull is performed to obtain a template reproducing the projection of the frontal sinus on the anterior cranial wall. All patients should be informed that it might be necessary to switch intraoperatively to a transfacial approach in case any unexpected contraindication is found during the surgery.

Lacrimal sac involvement Involvement of the orbital content Involvement of the bony walls of the maxillary sinus (except of the medial wall) Extension into the pterygopalatine or infratemporal fossa Posterior wall of the sphenoid sinus Extension to the hard palate Nasal pyramid involvement |

Operative Setup

Operative Setup

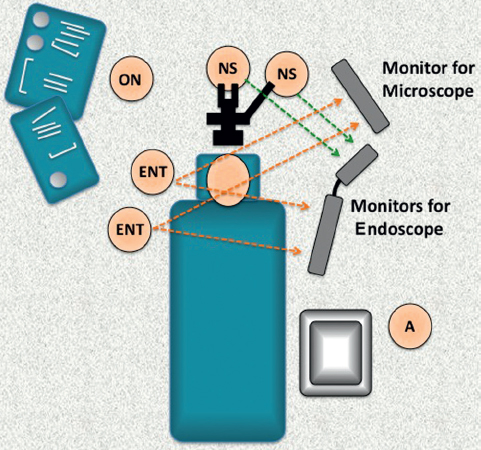

The surgery requires a double surgical team (neurosurgical and ear, nose, and throat [ENT]), an operating room nurse, and an anesthesiologist. The staff and equipment layout in the operating room is illustrated in Fig. 40.3. The presence of multiple screens (for the microscope and the endoscope) enables a panoramic view of the specimen, provides more accurate control of the resection margins, and facilitates interaction between the two surgical teams.

Endoscopic Phase

Endoscopic Phase

This phase requires the use of straight and angled rigid telescopes and dedicated instruments. If the neoplasm significantly obstructs the nasal fossa, it is necessary to perform tumor central debulking, usually with powered instruments, to allow centripetal collapse of the specimen walls and to facilitate identification of the lesion origin. The sphenopalatine artery is isolated and coagulated bilaterally, thus reducing bleeding during the entire procedure. The nasal septum is cut on its base parallel to the nasal floor, and then frontally with a vertical incision that reaches the nasal vault at the height of the frontal beak. Posterior mobilization of the nasal septum is obtained by performing wide bilateral sinusotomy and resecting the sphenoid rostrum to better define the posterior margin of resection.

Fig. 40.3 Layout of the surgical teams and instrumentation during a combined cranioendoscopic resection. All the surgeons are able to control both the transnasal and transcranial aspects of the approach with multiple monitors. A: anesthesiologist; ENT: otorhinolaryngologist; NS: neurosurgeon; ON: operating nurse.