11 Communication disorders

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• demonstrate an appreciation of the importance of good communication in clinical practice

• demonstrate an understanding of the importance of having a sound working knowledge of common speech and language problems in neurological rehabilitation

• compare and contrast ‘aphasia’ with ‘dysarthria’

• describe, compare and contrast Broca’s, Wernicke’s and conduction aphasia

• identify the key brain areas involved in each of these three types of aphasias

• demonstrate an understanding of the integration between various cortical areas in speech and language. Explain why categorising aphasia as ‘expressive’ or ‘receptive’ is too simplistic. Explain the strengths and limitations of categorising aphasia as ‘Broca’s’ or ‘Wernicke’s’

• demonstrate a basic awareness of how communication may be facilitated in people with speech and language impairment.

An overview of speech and language processes

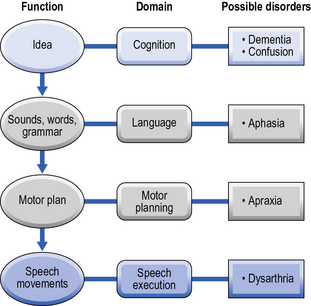

Before we examine impairments in speech and language, it may be useful to consider what is involved in normal communication. Think for a moment about a situation where you wish to express yourself, e.g. you have a question about what you have just read. Firstly, you need to formulate an idea in your mind, using knowledge and understanding you have stored already. People with cognitive impairments may have difficulty at this stage. Next, you need to formulate your question, and find the right words with the right meanings and place these in the appropriate logical order using the correct grammatical coding (e.g. correct tense). Aphasia is the collection of impairments at this level of communication. You must then select the correct motor program in order to articulate your actual question and use your articulatory muscles (for example your tongue and lips) to speak. Problems at these final levels are known as apraxia of speech and dysarthria respectively. Figure 11.1 gives an overview of the various functions required for communicating an idea, and examples of common disorders where these functions may be found to be impaired.

Aphasia: brain–behaviour relationship

Broca’s area

As mentioned earlier, the French neuroanatomist/anthropologist Paul Broca is often credited with the localisation of language function, specifically the motor aspects of speech production, in the left hemisphere of the brain. This is despite the fact that Marc Dax had published a paper on left hemispheric dominance for language some 25 years before Broca. There is actually little doubt that Broca was aware of the work of Dax, but he steadfastly refused to acknowledge the original theoretical contribution – ‘I do not like dealing with the questions of priority concerning myself. That is the reason why I did not mention the name of Dax in my paper’. Not only did he fail to acknowledge Dax, he actually claimed to be the first to discuss the theory of left hemispheric dominance! An interesting article was written by the authors Cubelli and Montagna (1994) who state that ‘the weight of evidence reported … . suggests that the theory of the left hemisphere dominance for speech must be attributed equally to Dax and Broca, and henceforth should be called the theory of Dax-Broca’. Let us leave this debate behind and examine the work of Broca a little more closely.

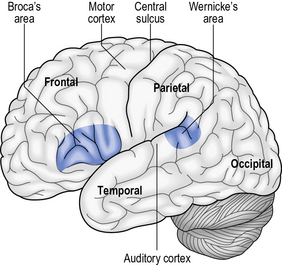

Broca (1861) examined a man, who was able to understand what was said to him but was unable to pronounce any words other than ‘tan’ over and over again. Although he was referred to as ‘Tan’, the unfortunate individual was a M. Leborgne who died a mere 6 days after examination. His death gave Broca the chance to examine the brain which revealed that the area damaged was a small region towards the front left hand side of brain – a region that became known as Broca’s area (Fig. 11.2).

Broca’s area is often referred to as the motor-speech area and it is located adjacent to the precentral gyrus of the motor cortex in the frontal lobes (see Fig. 11.2). This area controls the movements required for articulation, facial expression and phonation. Broca’s patients generally had good overall comprehension but their speech was often limited in their vocabulary and grammar which contained inaccurate pronunciation of words or parts of words which often made their speech unintelligible. More about the clinical presentation of people with Broca’s aphasia can be found below.

Wernicke’s area

Wernicke’s area, which includes the auditory comprehension centre, lies in the posterior superior temporal lobe near the primary auditory cortex at the junction of the parietal, temporal and occipital lobes (see Fig 11.2). Wernicke’s area plays a critical role in understanding both spoken and written messages (See Clinical application box 11.1), as well as being responsible for formulating coherent speech patterns. These ‘commands’ formulated in Wernicke’s area are transferred via a fibre tract, the arcuate fasciculus, to Broca’s area. Wernicke’s receives input from both the visual cortex in occipital lobe (an important pathway in reading, comprehension and describing objects seen) and the auditory cortex (essential for understanding spoken words).

Aphasia: clinical presentation

Expressive versus receptive aphasia

The division of patients into ‘expressive’ or ‘receptive’ aphasia is a very broad classification which was proposed by Weisenberg and McBride (1935).

Patients with expressive aphasia (also called motor aphasia) have difficulty translating their ideas into meaningful sounds resulting in non-fluent speech with pauses between words and or phrases. Expressive aphasia is associated with damage involving the anterior language centre of the dominant hemisphere, i.e. Broca’s area (see Fig. 11.2). It must be noted that people with expressive aphasia may also present with mild comprehension difficulties.

Receptive aphasia (also called sensory aphasia) is associated with damage to the posterior language area of the dominant hemisphere, i.e. Wernicke’s area (see Fig. 11.2). Patients with receptive aphasia present with difficulty in the comprehension of language. While their speech is normally fluent it is full of errors. For example, it may contain jargon (made-up words) or substitutions of words (paraphasias) amongst others.