43 Craniocervical Junction: Endoscopic Endonasal Approach

Paul A. Gardner, Daniel M. Prevedello, Amin B. Kassam, Carl H. Snyderman, and Ricardo L. Carrau

Introduction

Introduction

The craniocervical junction presents a surgical challenge because of the complexity of its anatomy and the difficulty accessing it. This region contains critical mobile joints that enable the majority of movement of the head relative to the neck and body in all directions. It also integrates the vertebral arteries, lower cranial nerves, and upper spinal nerves. The parapharyngeal internal carotid arteries (ICAs) limit access depending on the corridor of approach chosen. Anterior approaches for ventral pathology of the craniocervical junction present difficulties due to the craniofacial structures that must be transgressed. Traditional strategies for addressing this include facial, sublabial, or oropharyngeal incisions, which can require palatal or mandibular splitting. All of these strategies introduce morbidity related to the structures that are affected. The endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) provides an anterior corridor that avoids many of these morbidities.

Advantages and Limitations

Advantages and Limitations

The main advantages of the EEA to the craniocervical junction result from the angle of approach and the fact that it is the nasopharynx and not the oropharynx that is transgressed. The nose and paranasal sinuses provide rostral access and a rostral-to-caudal angle that provides excellent access to the majority of pathologies at the craniocervical junction. This is especially true in cases with any degree of basilar invagination.

The foramen magnum and upper cervical spine are located immediately behind the nasopharynx, which can be easily and directly accessed transnasally. The nasopharynx has significantly fewer and less virulent bacterial flora than the oropharynx.1 The palate is never affected by the approach, as the rostral-to-caudal angle of approach is parallel to the angle of the soft palate, thereby never transgressing it.

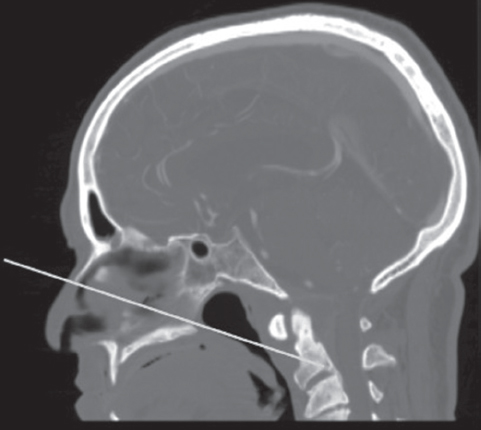

The angle of approach and the caudal limit of access for EEA to the upper cervical spine is determined by the nasopalatine (Kassam) line. This line is drawn on a midsagittal image (typically computed tomography [CT]) from the bony nasal bridge to the bony hard palate and extended into the depth (Fig. 43.1). Where this line crosses the second cervical vertebrae predicts the caudal limit of access. In our early clinical series, the actual point reached was an average of 12.7 mm rostral to the point predicted by the nasopalatine line.2 The difference is likely due to soft tissues, which are accounted for by the bony landmarks, variability in midsagittal imaging, and the fact that most cases do not require that the lowest possible point be decompressed.

Fig. 43.1 Midsagittal computed tomography (CT) reconstruction showing the nasopalatine line, drawn from the bony nasal bridge to the hard palate and extended into the depth. This approximates the caudal extent of access via an endonasal approach.

With the above caudal access as the main limitation, we have never encountered a case of degenerative pannus or os odontoideum compression that could not be accessed transnasally. Caudal access does become an issue when addressing tumors. Foramen magnum meningiomas may have disease that extends below the endonasal reach. In addition, bony tumors such as chordomas or sarcomas often are encountered below that level, and the approach must not limit the degree of resection. Often, the entire C2 body is involved, and this cannot be completely resected via an EEA. Disease into and below the body of C2 in the absence of basilar invagination requires either a transoral or transcervical approach.

Laterally, access is limited by the parapharyngeal ICAs and jugular foramen. Especially when dealing with disease in and around the ICAs, proximal vascular control becomes difficult or impossible. It is often necessary to add a cervical approach for both lower pole tumor dissection and proper ICA control in the event of an injury.

Indications and Preoperative Evaluation

Indications and Preoperative Evaluation

The common disease processes treated at the cervicomedullary junction are degenerative (rheumatoid and osteoarthritis) or posttraumatic atlantoaxial disease, meningiomas, and chordomas and other rare bony tumors. In the case of degenerative disease or benign tumors, the indications for EEA are no different from those for traditional anterior approaches. For example, if there is an arthritic pannus with minimal or no neural compression, a posterior fusion is adequate for treatment. However, if there is significant neural compression, especially if caused by bone rather than soft pannus, resection of the odontoid usually provides the quickest and most effective decompression.

With malignancy, accurate tissue diagnosis and, depending upon the tumor type, complete resection are usually the goals. If biopsy or palliation is the only goal, an EEA can provide a low morbidity corridor. However, all approaches must be considered when attempting gross total resection to ensure that the EEA is not being used by default. The limitations discussed above must be carefully evaluated prior to choosing an endonasal route.

Radiographic evaluation usually consists of both CT angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CTA shows the bony disease and involvement while evaluating limitations that may exist due to vascular involvement or anomalies (e.g., ectatic parapharyngeal ICA). MRI may better determine the extent of tumor involvement, soft tissue disease, and neural compression.

Other than radiographic and comorbidity evaluations to determine the goals of surgery and best approach, there are specific clinical symptoms that require careful preoperative evaluation when addressing disease of the craniocervical junction. Patients should be questioned closely for symptoms of dysphagia, aspiration, or voice changes. If these symptoms are present, they should undergo evaluation by an otolaryngologist to determine vocal cord function. If there is vocal fold paresis or paralysis, regardless of the approach being used, prophylactic tracheostomy should be strongly considered. This can greatly ease perioperative care and avoid further worsening caused by oral intubation.

Finally, range of motion should be evaluated preoperatively. This is helpful both for determining safe movement of the patient once under anesthesia as well as to guide clinical decision making related to the reducibility of compression and fixation options and consequences.

Surgical Technique

Surgical Technique

Perhaps the most critical part of a successful endonasal surgery is the development of a team of surgeons who can work together. We perform all surgeries with a team consisting of an otolaryngologist trained in open skull base surgery and endoscopic sinus surgery, and a neurosurgeon trained in open skull base surgery and comfortable with endoscopy. This team approach is not the usual skull base team approach where one surgeon performs one portion and then leaves, and the other surgeon then performs the other part. Rather, the two surgeons operate in parallel, with dynamic endoscopy and team problem solving. Dynamic endoscope movement takes full advantage of the endoscope by providing both close views when needed, mixed rapidly with panoramic views for orientation and instrument introduction. The team also learns to operate seamlessly, knowing what steps the other will take next and anticipating them. Finally, two surgeons working together are much more likely to avoid complications as a result of a single surgeon’s error.

Operating Room Setup

Patients with cervicomedullary compression have somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) monitoring before, during, and after positioning. This may detect a meaningful increase in compression related to positioning. In addition, patients undergoing EEAs for craniocervical junction disease may benefit from electromyographic (EMG) monitoring of the hypoglossal nerves. If relevant, in cases with lateral extension of pathology, EMG monitoring of all lower cranial nerves is useful.

When learning new techniques, especially involving the addition of an endoscope and the complex anatomy of the skull base, neuronavigation is critical. Although MRI can be very helpful with preoperative evaluation and operative planning, CTA guides much of the surgery. Avoiding vascular injury and identifying critical bony landmarks are foremost. This is especially true with the anteromedial corridor provided by an endonasal approach, which is chosen to avoid crossing critical neural structures.

We operate with both members of the team on the patient’s right side. We find this to be the easiest for right-handed surgeons, allowing their dominant hand the greatest freedom of movement. We prepare the midface and abdomen (in case of fat graft) with a Betadine solution, taking care to avoid the eyes. All patients are given a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin or equivalent with good cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) penetration and broad-spectrum coverage.

Odontoid Approach

Accessing the foramen magnum, ring of the atlas, and odontoid process is relatively simple. It is important to identify the middle and inferior turbinates and eustachian tubes. To widen the corridor, the inferior turbinates can be lateralized. As long as there are not anomalous ICAs, there are only mucosa, longus capitis muscle, and ligamentous attachments to address. Monopolar electrocautery can be used very effectively to remove these attachments between the eustachian tubes, which are typically medial to the parapharyngeal ICAs. We do not attempt a mucosal or muscle flap, as this is not necessary in the nasopharynx, which is not exposed to the forces of swallowing. In addition, preserving a flap limits the exposure either laterally or inferiorly.

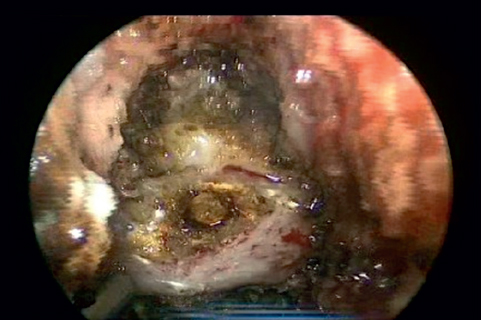

The width of exposure should be maximized prior to bony resection. There is a tendency with endoscopic approaches to funnel the exposure. The superficial exposure determines deep access. The ring of C1 is typically at the most caudal extent of reach via an EEA (Fig. 43.2). This can be confirmed with image guidance prior to soft tissue removal. The caudal reach can be improved slightly by drilling the maxillary crest flush with the hard palate. The hard palate itself can even be drilled posteriorly, but care must be taken to preserve the oral mucosa or many of the advantages of the endonasal approach are obviated. Curved drills or instruments may also improve caudal access. In general, angled endoscopes are not used, as it is instrumentation that is the limitation, not the view.

Fig. 43.2 Endoscopic view of the exposure of the ring of C1 at the caudal extent of endonasal access.