CHAPTER 180 Craniopagus Twins

Historical Perspective

The first documented illustration of craniopagus twins dates from the 15th century, describing a set born in Bavaria, Germany, in 1491 as a “warning from God” (Fig. 180-1). A famous case of craniopagus parasiticus was reported by Sir Everard Home1 (1756-1832) in his collected works as the “Boys of Bengal,” a set of twins born in India in the 1770s (Fig. 180-2). In the early 19th century it became quite popular to exhibit conjoined twins in traveling road shows and circuses as “freaks” of nature and even to distribute postcards and autographed pictures of them (Fig. 180-3).

Classification and Demographics

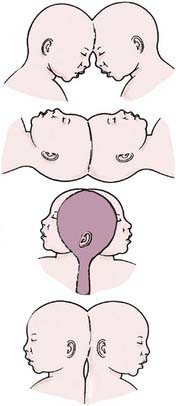

In his fundamental work on teratology, Forster2 introduced the term craniopagus to describe twins joined at the head. Craniopagus twins are defined by a union of the calvaria only; unions involving the foramen magnum, skull base, vertebrae, or face are classified separately (e.g., cephalopagus, parapagus, rachipagus, diprosopus) (Fig. 180-4).3 In craniopagus twinning, the union is rarely symmetrical and may involve any portion of the head. An infinite number of configurations can occur, based on the attachment location and the degree of individual rotation of one head on the other. Variations in the degree of conjoining or sharing of underlying structures such as the meninges, venous sinuses, and cortex add to the individual nature of each case.

FIGURE 180-4 Variations of the union in craniopagus twins.

(Redrawn from Spencer R. Conjoined Twins: Developmental Malformations and Clinical Implications. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2003).

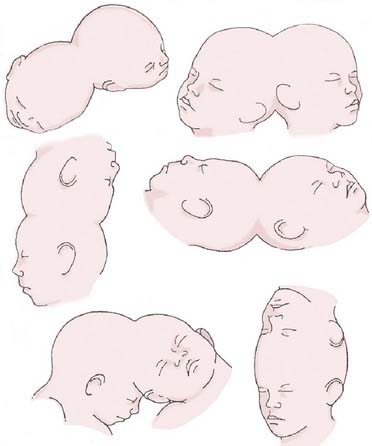

Several authors, beginning with O’Connell,4 have attempted to classify the numerous phenotypic variations seen in craniopagus twins. According to O’Connell’s classification schema, partial craniopagus twins have limited surface area affected, with intact crania or minimal cranial defects. Total craniopagus twins share an extensive surface area with widely connected cranial cavities. O’Connell4 subclassified “vertical” craniopagus twins—”parietal craniopagus,” according to the classification of Bucholz and associates5 (Fig. 180-5)—into types I through III, based on the degree of rotation of one on the other. Stone and Goodrich,6 in an effort to evaluate outcomes among different types of twins, used the partial and total divisions described by O’Connell and also defined two main subtypes: angular and vertical. Angular craniopagus twins have an intertwin longitudinal angle less than 140 degrees, regardless of axial rotation. Vertical craniopagus twins display a continuous longitudinal cranium and are further subdivided based on the degree of intertwin axial facial rotation: type I, rotation less than 40 degrees (formerly O’Connell type I); type II, rotation between 140 and 180 degrees (O’Connell type II); and type III (“intermediate”), rotation between 40 and less than 140 degrees (O’Connell type III).6

Craniopagus twins are extremely uncommon, occurring once in every 0.6 to 2.5 million live births (Table 180-1).6,7 The cause of the conjoining of twins is unclear; both “incomplete fission” and “fusion” hypotheses have been proposed by embryologists.3,8 There are no known environmental or genetic factors. Interestingly, the female-to-male ratio is nearly 4 : 1, although this has not been correlated with any cause of the condition.

TABLE 180-1 Demographic and Embryologic Characteristics of Craniopagus Twins

| INCIDENCE |

| GENETICS |

| CAUSE |

| MORTALITY |

| Conjoined twins: 40% stillborn; 33% die in perinatal period |

An extensive review of the literature from 1919 through 2006 notes 64 well-documented cases of craniopagus with 41 separation attempts—29 performed as single-stage separations and 12 as multistaged separations.9

Surgical Separation

Risk Stratification

The decision to separate craniopagus twins is obviously fraught with serious considerations. Stone and Goodrich6 proposed their classification system in part to better understand the outcomes after surgical separation. It is now recognized that shared dural venous sinuses present significant difficulties when proceeding with separation, but numerous other risk factors must be assessed when evaluating craniopagus twins for separation. Critical to the surgical decision-making process is an understanding of the degree of shared scalp, calvaria, and dura (independent dural envelopes or incomplete dural separation); the amount of separation, interdigitation, or fusion of cortex or deeper structures; the extent of shared arterial connections and cross-flow; the extent of shared or common venous sinuses and drainage; the presence of paired or separate venous outflow; the presence or absence of independent deep venous drainage; and the presence of common or separate ventricular systems and hydrocephalus.10 Because each of these factors has serious implications for the surgical strategy, we proposed a scheme by which individual cases can be evaluated to determine the surgical risk (Table 180-2).10 Although each case involves many unique considerations, this scheme, which assigns point values based on the aforementioned criteria, can be used to gain a preliminary understanding of the degree of risk associated with a separation attempt; a higher score is indicative of a more difficult separation.

TABLE 180-2 Surgical Risk Stratification

| CHARACTERISTIC | SCORE* |

|---|---|

| Scalp | |

| Minor surface area shared (<10 cm2) | 1 |

| Major surface area shared (>10 cm2) | 2 |

| Calvaria | |

| Minor surface area shared (<10 cm2) | 1 |

| Major surface area shared (>10 cm2) | 2 |

| Dura Mater | |

| Independent dural envelope surrounds cortex | 1 |

| Dura shared along one or more planes | 2 |

| Neural Tissue | |

| Completely separate | 1 |

| Interdigitated but not fused | 2 |

| Minor areas of fusion (<5 cm2 total surface area) | 3 |

| Major areas of fusion or involvement of eloquent cortex (>5 cm2 total surface area) | 4 |

| Arterial Connections | |

| None | 1 |

| Minor feeding branches (M4, A4, P4) | 2 |

| Distal branches (M3, A3, P3) | 3 |

| Proximal branches (M2, A2, P2) | 4 |

| Major vascular trunks (M1, A1, P1, ICA) | 5 |

| Venous Connections | |

| None | 1 |

| Separation of major sinuses with minor shared draining veins | 2 |

Shared along anterior  of superior sagittal sinus and/or shared distal (transverse/sigmoid) of superior sagittal sinus and/or shared distal (transverse/sigmoid) | 3 |

Shared along posterior  of superior sagittal sinus without involvement of the torcula of superior sagittal sinus without involvement of the torcula | 4 |

Shared along posterior  of superior sagittal sinus with involvement of the torcula of superior sagittal sinus with involvement of the torcula | 5 |

| Deep Venous Drainage | |

| Present | 1 |

| Absent | 2 |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (Ventricular Anatomy) | |

| Separate ventricular systems | 1 |

| Shared ventricular system | 2 |

| Venous Outflow | |

| Ipsilateral | 1 |

| Contralateral (crossed) | 2 |

| Arterial Flow | |

| Ipsilateral | 1 |

| Contralateral (crossed) | 2 |

A, anterior cerebral arteryica; ICA, internal cerebral artery; M, middle cerebral artery; P, posterior cerebral artery.

* Higher score equates with more difficult separation. Minimum score = 10; maximum score = 28.

From Browd SR, Goodrich JT, Walker ML. Craniopagus twins. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:1-20.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree