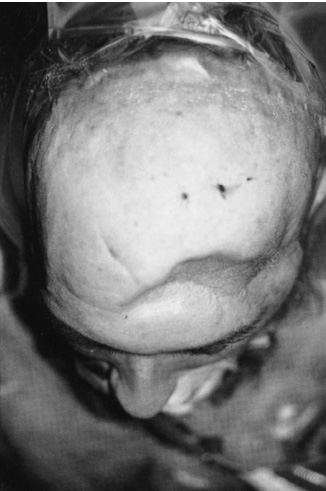

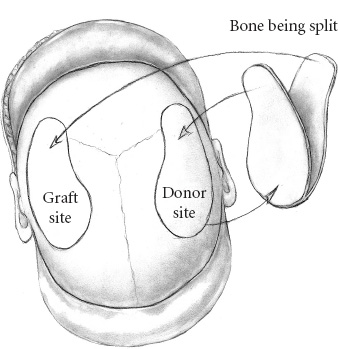

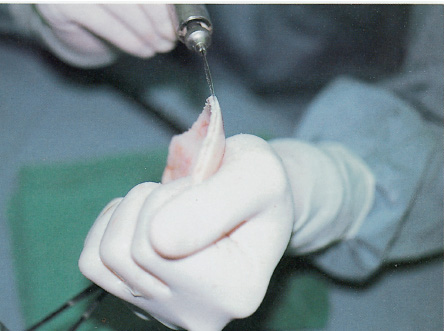

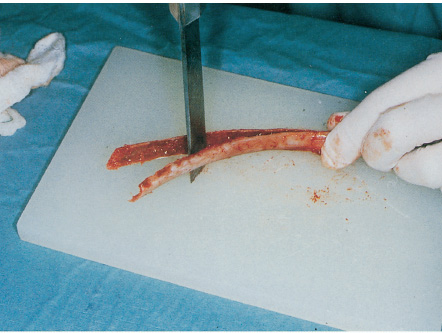

A cranioplasty is a procedure for repairing a defect of the calvarium. A successful cranioplasty is one in which the cranial defect is repaired and then heals and grows with the child in the anatomically and aesthetically appropriate fashion. The location of the defect is extremely important. Defects in the frontoglabellar region require much more attention to detail than a defect behind the hairline. Contours, healing scars, alignment of eyebrows, orbital dystopia, and the like are all important factors. In the pediatric population (and often in the adult population), the indications for a cranioplasty are repair of a skull defect; these defects are most commonly a result of trauma or tumors of the skull and brain (Fig. 18–1). Children are active, and, lacking the “normal” senses of the adult, rarely appreciate a defect in the skull. A simple writing instrument, such as a pen or pencil, can become a lethal weapon in the hands of a playful child with a skull defect. A simple fall on the jungle gymn can lead to extraordinary damage to the brain in a child without adequate skull coverage and protection. The surgical indications for repair of a skull defect are straightforward: repair of any significant open bone defect where there is a risk of potential penetration of the brain. The preoperative evaluation of a child with a skull defect is also straightforward. A plain skull series is done to outline the defect and to allow calculations of the area that needs to be repaired. If available, three-dimensional (3-D) computed tomography (CT) is extremely useful in outlining the defect and helpful to the family in the pre-operative evaluation. A routine axial CT is important in outlining any underlying brain injury, the presence of encephalomalacia, and to rule out any sequestered debris or potential infectious material. An axial CT also can provide additional information about bone thickness and the availability of material for split-thickness calvarial grafts. Most cranioplasties are done in elective situations and typically are delayed until 4 to 6 months after the original injury. Any evidence of infection at the injury site should be ruled out. Routine preoperative blood screening also should eliminate any potential of blood infection or sepsis. Any evidence of infection or sepsis is a definite contraindication to surgery. In cases where the child will require a helmet, we have our child-life specialist meet with the family to discuss the helmet requirements, such as when it must be worn and its purpose. Not uncommonly, we have the child wear the helmet for a couple of weeks preoperatively to become accustomed to it. In the younger child, it is important to appreciate the social stigma associated with wearing a helmet, especially in school, and these psychosocial problems should be addressed early. Cranioplasties often are done in association with plastic surgery colleagues. The input of the plastic surgeon can be extremely useful, particularly for defects that involve the orbit and forehead regions. As part of the operative planning, we often include conferences with the radiologist, plastic surgeon, anesthesiologist, and child-life specialist to provide input on what each team can contribute to the case. In cases with extensive postoperative rehabilitation and physical therapy planned, we also ask the physical therapy and rehabilitation team to join the conference. Often, many questions are asked about the length and intensity of therapy and the restrictions implied by a cranioplasty; these issues are best addressed in the conference. General anesthesia with an endotracheal tube is almost always used in cranioplasty repairs. Occasionally, a laryngeal mask is used in cases of short duration (i.e., less than 2–3 hours). In patients with large bone defects (i.e., greater than 8 cm), the potential need for a blood transfusion must be considered and blood made available for these cases. In cases that involve the face and orbit, the endotracheal tube must be well secured because there is often a good deal of movement of the head during the surgery to evaluate for aesthetic contours during reconstruction. We routinely give antibiotics (oxacillin 25 mg/kg of body weight) as soon as anesthetic is induced and well before the skin incision is made. The positioning of the patient should be such that access to the repair site is generous. In cases where bone is to be harvested, both sites need to be in the prepared field. We have found the horseshoe head rest the most reliable in frontoorbital and vertex approaches. For defects of the lateral regions, the head is turned to the appropriate side and then rested on a soft donut cushion. Most cranioplasties are done in areas of previous injury or surgery. Therefore, a skin incision from the previous surgery is present. In the operative planning, the original scar can be incorporated in the incision and extended as necessary. All incisions should be planned in such a fashion that no vascular pedicle is comprised; close (<3 cm) parallel incisions always should be avoided. The vascular supply to the scalp arises from the base of the skull and ascends the scalp in a palisade fashion; therefore, knowledge of this anatomy and the various vascular anastomoses always should evaluated in the surgical planning. A common error is made when the skin incision is too close to the forehead hair line. A forehead incision should be placed either in a natural skin crease or at least 2.5 cm behind the hairline, even more if possible. We prefer to make wavy-type incisions, if possible, to prevent later hair parting over the incision when the hair is wet. Curvilinear incisions over the temporalis region also seem to reduce the incidence of hypertrophic scar formation that often occurs in this area. The preparation of a cranial defect for repair remains the same in all cases no matter what the source of the defect. The surgical bed must be clean and free of debris of any kind. Both the surgical bed and the overlying surgical flap must be well vascularized. If these conditions are not present, neither the flap nor the implant will heal. In the case of repairs in the vicinity of the frontal sinuses, it is extremely important to cranialize the sinus or obliterate it with a pericranium flap. In elevating the skin flap, the pericranium is brought up as a second layer with its pedicle kept intact, thereby developing a vascularized pedicle flap that can be easily rotated into a number of different positions. Bone edges to be incorporated in the repair have to be “freshened,” that is, cleaned and debrided of any scar tissue or debris. The bone edges should be burred to provide a fresh bleeding edge. The use of bone wax along the freshened bone margins is discouraged because this material retards bone bridging and can provide a nidus for later infection. We use thrombin-soaked Gelfoam with pressure to stop the bleeding. Only in cases of large emissary veins where bleeding is difficult to control do we use bone wax, and then as little as is necessary. Meticulous hemostasis and gentle handling of soft tissues are always obligatory. Autologous bone always should be considered first as the primary repair material in cranial defects, particularly in a growing child. Autologous bone heals most naturally, will grow with the child, and has the lowest incidence of infection. The surgeon has three types of autologous bone available for reconstruction: (1) calvarium, (2) costochrondral rib grafts, and (3) iliac crest. Each has advantages and disadvantages. In cases in which a bone graft is needed to close a bone defect, the best source of autologous bone remains the calvarium. The skull has a natural mirror image that allows the surgeon to harvest contralateral bone and that often possesses a contour that closely matches the defect (Fig. 18–2). Because the skull is bilamellar, it can be split along the diploë, generating two pieces of bone, one to be placed in the defect and the other back at the donor site (Fig. 18–3 through 18–8). Using a soft malleable piece of metal, a template of the defect is designed and applied to the contralateral skull in various positions until an area is located that closely matches the defect to be repaired. The donor graft is always made 4 to 5 mm larger than the defect to allow for the bite of the craniotomy drill and gives additional trimming room for positioning the graft. The flap is elevated using standard craniotomy techniques with copious irrigation so that the heat generated by the craniotome does not burn the bone. As discussed already, the use of wax on bleeding bone edges is discouraged. FIGURE 18–2. An artistic reconstruction on obtaining a split calvarial bone graft. In this case (see Fig. 18–1), the defect is over the right parietal temporal region. A mirror image bone is harvested from the contralateral side and elevated. Once the bone is split, the inner table will go back to the donor site, and the outer table is placed in the defect. Once the bone flap has been harvested, it can be split in any of a number of ways. In the young child (i.e., younger than 2 years), a freshly sharpened osteotome handled much like a knife allows one to slice the bone apart (Fig. 18–5). In the child older than 2 years of age, the bone usually has become thick enough to split with fine, thin, high-speed bits, such as the C-1 attachment for the Midas Rex drill. Depending on the width of the flap, curved osteotomes and reciprocating saws with flexible blades are also helpful in splitting the bone (see Figs. 18–3 and 4). The thickest bone for harvesting is over the frontal and parietal boss regions. The thinnest bone (and hence least useful) is over the temporal regions—considerations to be kept in mind when harvesting bone. It is always desirable to create large bicoronal exposures when the need for large grafts is expected. Fixation of bone plates in the pediatric population has been a recent focus of discussion. We try not to use fixation miniplates in children younger than 3 years of age; despite being “mini,” they can be felt easily through the skin, which is disconcerting to the child and parents. We also have had personal experience of unacceptable plate migrations such that at later reoperation, we found that the plates had migrated intracranially and in two cases were actually within the dura or brain parenchyma. With rare exception, we now use only sutures (e.g., Vicryl or Neurolon) to stabilize the flaps. The only exception is the occasional instance in which exceptional stability of the repositioned flap is required, as in repairs around the orbits. If the flap repair is being done well behind the hairline and the child is older than 3 years of age, the use of miniplates is acceptable. Once the bone flap has been replaced, the edges are contoured using a high-speed burr so that they are not palpable through the skin. In the infant, the bone can be contoured easily using a Tessier rib bender. Radial (fanlike) osteotomies also can be used to provide additional contouring. In the older child with a thicker, less malleable skull, the pericranium is left attached to the bone when the craniotomy is done. A series of radiating osteotomies is created on the inner surface of the bone that incorporate the inner table and extend well into the diploë without cutting through the outer table. The bone then is fractured using the pericranium as a hinge. This is a useful way to tailor the contours of hard bone.

SURGICAL INDICATIONS AND PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

PREOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

OPERATIVE PLANNING

INTRAOPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

Anesthetic Techniques and Positioning

Skin Incision

Preparation of the Cranial Defect

Techniques for Cranioplastic Reconstructions

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree