In children, tumors of the spinal canal constitute a smaller proportion (5 to 10%) of tumors of the central nervous system than in adults. The various types of tumors that occur in children also differ from those seen in adults. Intradural extramedullary tumors, such as meningiomas, schwannomas, and neurofibromas, the most common tumors in adults, are rarely found in children. The most common acquired, nontraumatic cause of paraparesis in children is compression of the spinal cord by malignant epidural tumor deposits. These deposits differ from those found in adults in the histologic and biologic features of the tumors involved, the location and direction of compression, the degree of bone involved, and the general medical condition of the patient. Table 15–1 summarizes the various types of neoplasms, both intramedullary and extramedullary, found in the spinal canals of 635 pediatric patients in 10 large series published between 1953 and 1990 (see Yamamoto and Raffel, 1999, for references). Myxopapillary ependymoma of the filum terminale and cauda equina, a rare neoplasm that appears in children as a extramedullary lesion, is underrepresented in these previous series. Thirty-five percent of neoplasms in the spinal canals of children are located extradurally. Table 15–2 summarizes the tumor pathologies that caused epidural compression of the spinal cord in children in four series (see Yamamoto and Raffel, 1999 for references). It has been suggested that 3 to 5% of children with a systemic malignant tumor have a compressed spinal cord sometime during their illness. In many of these children, compression of the spinal cord is the first sign of malignancy. The rarest spinal lesions in children are diffuse sub-arachnoid, or leptomeningeal, tumors, which usually stem from the dissemination of a posterior fossa tumor, such as a primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Tumors of the posterior fossa rarely present with spinal symptoms; nonetheless, about 20% of primitive neuroectodermal tumors in the posterior fossa have already disseminated in the cerebrospinal fluid at presentation. Leptomeningeal tumors cannot be treated surgically. A surgical approach is indicated only if the patient’s diagnosis is unknown. In patients with extramedullary spinal tumors, weakness and pain are the most common symptoms. The weakness is usually of the upper motor neuron type and is associated with increased tone and hyperactive deep-tendon reflexes. If the conus medullaris or cauda equina is involved, the weakness may be flaccid. In infants and toddlers, the weakness may be subtle and therefore difficult to detect. Pain is an important early symptom in children with spinal tumors. Pain occurs most commonly in the back and is reported by 28 to 59% of patients. Depending on the level of the lesion, some children have radicular pain radiating into the arm or leg or around the chest wall. Radicular pain is reported most often by patients with intradural extramedullary and extradural lesions. In a child with known malignant disease, back or radicular pain requires immediate evaluation to determine whether the spinal cord is compressed. Similar pain in a child with no known malignancy also indicates a careful evaluation to determine the cause. TABLE 15–1. Tumor Type in 635 Pediatric Patients in 10 Large Seriesa

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION AND SURGICAL INDICATIONS

Signs and Symptoms

| Location/Tumor Type | No. of patients (percent) |

| Intramedullary | 189 (29.7) |

| Astrocytoma Ependymoma Lipoma | 114 50 25 |

| Intradural extramedullary | 156 (24.6) |

| Dermoid Neurofibroma Schwannoma Meningioma Epidermoid PNETb Hemangioepithelioma | 39 28 20 17 14 30 8 |

| Extradural | 219 (34.5) |

| Sarcoma Neuroblastoma Teratoma Metastasis Ganglioneuroma Lymphoma | 67 64 35 29 19 5 |

| Other | 71 (11.2) |

aFor references, see Principles and Practice of Pediatric Neurosurgery.

Table 15–2. Epidural Tumor Type in 246 Pediatric Patients in Four Large Seriesa

| Tumor Type | No. of Patients (Percent) |

| Neuroblastoma | 64 (26.0) |

| Ewing’s sarcoma | 52 (21.1) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 31 (12.6) |

| Osteogenic sarcoma | 29 (11.8) |

| Lymphomab | 19 (7.7) |

| Undifferentiated sarcoma | 12 (4.9) |

| Germ cell tumorsc | 12 (4.9) |

| Leukemia | 7 (2.8) |

| Wilms’ tumor | 4 (1.6) |

| Other | 16 (6.5) |

aFor references, see Principles and Practice of Pediatric Neurosurgery.

cEmbryonal cell carcinoma, endodermal sinus tumor, and teratoma.

Sensory disturbances are also common in patients with spinal tumors but are difficult parameters to determine in the young patient.

Bladder or bowel dysfunction is also common, occurring in about half of patients with severe compression of the spinal cord. A loss of bladder control in a toilettrained child should raise the suspicion of a spinal lesion.

An abnormal curvature of the spine occurs in about one fourth of children with spinal tumors and may be the initial sign that indicates a lesion. In any child with a progressive abnormality of spinal curvature, the diagnosis of intraspinal neoplasia should be considered.

Radiological Studies

Because of the increased anatomic detail gained without the need of a lumbar puncture, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging with and without intravenous contrast is preferred over computed tomography (CT) myelography to identify spinal cord neoplasms. Avoiding a lumbar puncture eliminates two important risks: (1) bleeding from thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy associated with some malignant diseases, and (2) accelerating the rate of neurologic deficit through the loss of cerebrospinal fluid. In our experience, MR imaging is at least as sensitive as myelography combined with CT, and it provides superior anatomic details of tumors both inside and outside the spinal canal. Administration of Gd-DTPA aids in the identification of intradural—extramedullary nodules as small as 2 to 3 mm and easily depicts the leptomeningeal spread of tumor.

Plain radiographs may help to define the region of the spine to be scanned because they reveal abnormalities in half of patients with spinal cord tumors. Intradural extramedullary tumors can thin or cause sclerosis of the pedicles. A tumor that extends through a neural foramen enlarges that foramen, which is best visualized on oblique films. An enlarged foramen indicates a tumor of the nerve sheath or a paraspinous tumor that enters the canal at that level. Malignant tumors of the bone and epidural metastases erode bone and may cause a vertebral body to collapse. Paraspinous masses may be seen on plain radiographs in association with an enlarged foramen or bony destruction. Although MR imaging is usually the initial imaging study done, plain radiographs may be helpful in defining bony anatomy and alignment and also can serve as a baseline for comparison if the patient develops scoliotic changes after treatment.

Previously, myelography with watersoluble contrast material was used extensively in the evaluation of suspected intraspinal lesions in children; however, sudden deterioration after a lumbar puncture has been reported in patients with intraspinal neoplasms. Therefore, myelography should be reserved only for patients who require an emergent study when MR imaging is not immediately available. Other occasions include a patient with severe scoliosis, which makes it difficult to interpret MR findings.

In such cases, CT scanning after intrathecal watersoluble contrast administration is an important adjunct to myelography for imaging spinal tumors. Because a small amount of contrast medium may pass around a high-grade block seen on a myelogram, a CT scan can often define the upper extent of the lesion without the need for a second injection of contrast material above it. CT scanning with intrathecal contrast is more sensitive than myelography alone in detecting small drop metastases and lesions in the epidural space. CT scans delineate the bony anatomy especially well; thus, they are the best choice for determining the degree of bone destroyed by an invasive tumor.

Surgical Indications

Surgical decompression is indicated for patients with severe compression of the spinal cord, regardless of the type of tumor; for symptomatic patients newly diagnosed with sarcomas; for patients with symptomatic compression who have no diagnosis; and for patients whose neurologic function deteriorates during nonsurgical therapy.

The treatment of intradural extramedullary tumors is primarily surgical. These tumors are usually nerve sheath tumors or meningiomas, which are separated from the surrounding tissue by a distinct margin. This margin allows total excision in almost all patients. Some nervesheath tumors extend into the extradural space, through the neural foramen, and into the paravertebral soft tissue. In these cases, the surgeon may need to carry out a second extraspinal resection to remove the remaining tumor.

Extradural spinal neoplasms causing spinal cord compression, mostly “small cell blue” tumors, such as neuroblastoma and lymphoma, can be treated successfully with chemotherapy or radiation therapy. On the other hand, most sarcomas require operative decompression. The goal of decompression is not to remove all tumor, but to decompress the cord. Adjuvant therapy is indicated in almost all instances.

PREOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Each patient must be evaluated carefully for possible instability of the spine caused by destruction of the spinal column and paraspinal structures. This evaluation should be done both clinically and radiologically. If the patient has a known primary malignancy, preoperative staging with radiological studies is required to assess possible metastatic lesions in other organs. Bleeding tendencies associated with malignant disease should be carefully corrected before surgery.

OPERATIVE PLANNING

For a patient with significant spinal cord compression, perioperative use of methylprednisolone can be considered, although there are no scientific data to support this to date. Intraoperative monitoring of somatosensory-evoked potentials (SSEP) is used by some surgeons, but there is controversy about whether the monitoring can give up-to-the-moment feedback and whether the surgeon must modify the procedure according to changes in the SSEP. We do not usually use SSEP at our institute. If the lesion is expected to be extremely vascular, blood for a transfusion should be prearranged according to the patient’s body weight. We often use intraoperative ultrasound to localize intradural extramedullary lesions as well as intraoperative radiography to confirm the level of bone work.

INTRAOPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

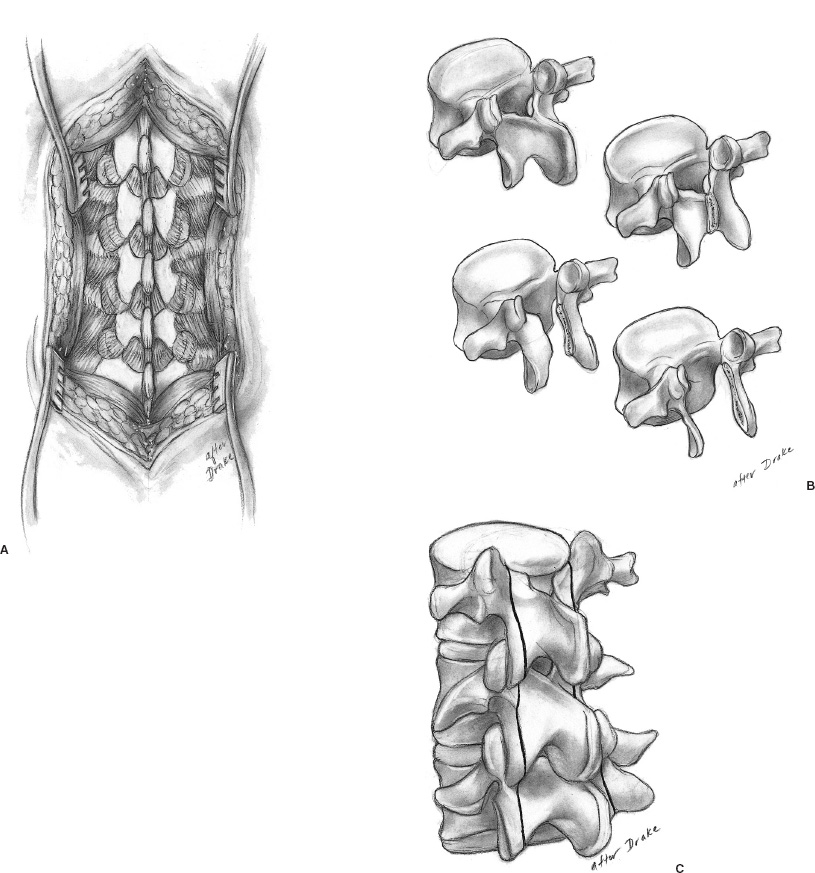

For small children, minimizing blood loss during any surgery is crucial. We always use a hot knife (Shaw Scalpel, Oximetrix, Mountain View, CA) and a bipolar coagulator of an appropriate size. Respecting anatomic dissection planes is helpful in preserving normal vasculature as well as minimizing blood loss. Laminectomy is usually carried out using different shapes of rongeurs, kerrison punches, or a high-speed drill with diamond bits (Figs. 15–1A and B). Care must be taken to avoid compressing the spinal cord further. Laminotomy can be done using the Midas Rex (Medtronic Midas Rex, Fort Worth, TX) with the footed attachment (Fig. 15–1C). This must be done carefully so as not to compromise the already restricted spinal canal.

Intradural Extramedullary Tumors

The surgical approach for intradural extramedullary tumors in children does not differ from that used in adults. Most meningiomas, neurinomas, myxopapillary ependymomas, and dermoids are operated on through a laminectomy either with or without laminoplasty (see section on surgical complications). Intraoperative ultrasound can be useful in localizing the extension of the tumor and minimizing the levels of the laminectomy. The microscope and microdissection tools are indispensable for preserving normal neural structures. In some instances, electrophysi ologic monitors, such as SSEP to monitor dorsal column function during dissection or electromyography to identify nerve roots, offer important information. Myxopapillary ependymomas of the filum terminale and conus medullaris also can be removed surgically. Meticulous attention should be paid to preserving the tumor capsule because any spillage of tumor cells into the subarachnoid space can be a source of recurrent tumor or spinal dissemination. Radiation therapy of disseminated myxopapillary ependymomas has been unsatisfactory.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree