(1)

Hand Surgery Department of Clinical Sciences, Malmö Lund University Skäne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden

Abstract

Creative hands can be traced back to cave art, decorations and various types of artistically designed objects created over the last 100,000 years, primarily in South Africa and Europe. As a symbol of creativity, the hand plays a key role in our culture, particularly in art and music. However, many of the most well-known artists and musicians suffered from various types of hand problems but were still able to perform their art, thanks to well-preserved brain function – their creative capacity. Musicians lacking one arm have been able to perform music at very high artistic levels. The brains of experienced musicians may be somewhat different from the brains of nonmusicians, with well-developed white matter and an enlarged corpus callosum connecting the two brain hemispheres, and in violin players the cortical representation of the left hand may be enlarged. Experienced musicians may view their instrument as an integral part of their bodies.

When did the ability for creative thinking and the desire to decorate and beautify items and tools of everyday life emerge among our ancestors? And when did the desire arise to shape and design items for self-decoration? Creative hands can be traced back to the development of man. Some of the oldest known artistically designed items are a couple of carefully polished pieces of ochre with engraved geometric patterns characterised by regular engraved crossed lines that were found in the Blombos cave in South Africa. It has been proposed that these nearly 77,000-year-old items bear witness to artistic thinking and an early symbolic tradition [1]. Thirteen 100,000-year-old engraved ochre pieces were recently discovered in the same cave together with a processing workshop where a liquefied ochre-rich mixture was produced and stored in abalone shells [2]. In the Blombos cave, scientists also discovered the oldest known jewellery made of shells with drilled holes to wear as a necklace [3]. The findings from the Blombos cave indicate that a symbolic tradition existed among our ancestors 100,000 years ago or even earlier. Paul Mellars at the University of Cambridge argues that the ability for aesthetic and symbolic thinking might have existed since the emergence of our species Homo sapiens 170,000–200,000 years ago. But no one can understand and interpret the meaning and symbolism of these items for certain.

An interesting example of the use of a type of very early graphic art for communication purposes is symmetric engravings on 60,000-year-old ostrich eggs. For 10 years, Pierre-Jean Texier at Bordeaux University and his associates collected 270 such ostrich eggs at the Diepkloof Rock Shelter, a cave in west South Africa. Various engravings were repeated several times on the egg shells over long time periods. Scientists interpreted this as an indication of symbolic communication among individuals, a ‘modern’ human behaviour. The eggs were most likely used as containers, and the signs might have symbolised either the content of the container or the name of its owner [4].

It was long believed that the most evident proof of high-level aesthetic thinking by our ancestors is the pictures and paintings that were discovered in the caves of southern Europe and at many other locations worldwide. Compared to the findings from the Blombos cave, the European cave paintings are considerably younger – they have been dated at 10,000 to 40,000 years old. These paintings were made using red and yellow ochre, hematite, magnesium oxide and charcoal. Among the oldest paintings are those in the Chauvet cave in southern France, made 32,000 years ago. This cave contains a rich gallery of animal images. In some locations the silhouettes of animals were etched in the cliff wall before they were coloured. The most common motifs are large wild animals like aurochses, bison, lions, bears and rhinoceroses, but there also are pictures of wild horses, reindeer and stags [5]. In the Chauvet cave there are spectacular images of lions that were painted in harmony with protruding irregularities from the wall so that the animals almost seem to emerge from the cliff wall [6]. Images of animals also dominate the cave at Niaux in the French Pyrenees [7].

The animal images can be interpreted as a type of hunting magic. The images most often depict the animals that they hunted, but sometimes they represent animals that competed with the hunter and predators that were very dangerous to the hunters. The animal pictures are not static icons but represent animals running, swimming, hunting, fighting, copulating and giving birth.

Prominent among several other caves with paintings showing a high level of artistry is the Lascaux cave in Dordogne in southern France (Fig. 12.1). It was accidentally discovered by some 13-year-old boys in September 1940. This cave, containing thousands of old paintings and engravings about 17,000 years old, has been called ‘the Sistine Chapel of prehistory’ and is on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. But the images have been severely damaged, possibly due to climate changes or all the carbon dioxide exhaled by many visitors over the years. Massive attacks of algae caused the paintings to suffer from fungus that spread dark patches over the cave walls. For many years intensive efforts have been made to reverse this development, and 30 years ago the cave was closed in order to return it to its original condition [8].

Fig. 12.1

Works by early creative hands. A cave painting from the Lascaux cave, about 20,000 years old, representing a bellowing deer with enormous antlers. The meaning of the dots and rectangle below the painting is not known (From National Geographic Oct 1988. Photo: Sisse Brimberg/National Geographics)

The hand is a symbol of creativity and spiritual power. For many people the most creative and powerful hand is the hand of God, which in the religious perspective created and modelled the earth, heaven and man. On the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, God’s finger, as painted by Michelangelo, symbolises the basis for the creation of man – God’s right index finger transfers the spark of life to Adam by touching his left hand (Fig. 12.2).

Fig. 12.2

God transmits the spark of life to Adam. Michelangelo, painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

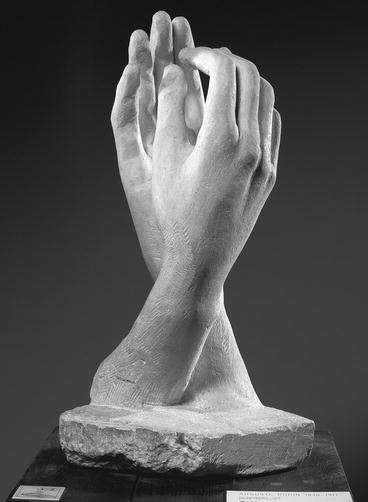

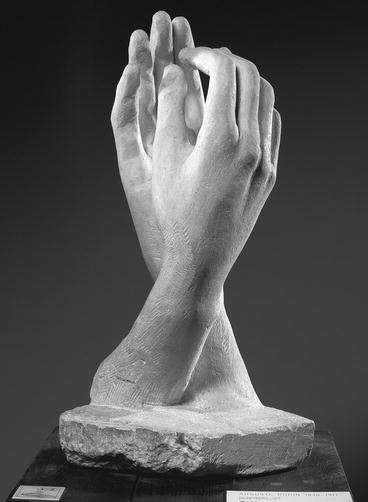

Hands often have a prominent and important role in paintings and sculptures by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin (Fig. 12.3), and in many of Swedish sculptor Carl Milles’ works the shape and posture of the hands contribute to the figures’ vitality and expressions.

Fig. 12.3

The Cathedral, Auguste Rodin 1908. Two hands in prayer form the peaked arch. No 1001, stone, 64 × 29.5 × 31.8 cm (Photo: Christian Baraja. Musée Rodin, Paris)

Carl Milles visited Rodin’s studio in Paris in 1902 and was deeply touched by a marble sculpture representing God’s hand creating man (Fig. 12.4). Milles was inspired to create a sculpture on the same theme, however, symbolising man’s existence in God’s hand with man balancing on the thumb and index finger (Fig. 12.5).

Fig. 12.4

The Hand of God. Auguste Rodin 1908. No 988, marble 95.5 × 75 × 56.5 cm. God’s hand modelling man (Photo: Christian Baraja. Musée Rodin, Paris)

Fig. 12.5

Man balancing on God’s hand. The Hand of God, 1949–1953, by Carl Milles (Courtesy of Millesgården, Stockholm. Photo: Lars Ekdahl © Millesgården, Stockholm)

Every day we see creative hands all around us. It is easy to be impressed by the creative power and skill of hands in many activities and occupations where handwork has not yet been replaced by automatic and computerised processes. The silent knowledge, possibilities and improvisation capacity of hands are still the basis for several occupations, even if many handicraft traditions and inherited knowledge are at risk of disappearing. We can still be aware of the impressive handicraft skills exhibited by carpenters, blacksmiths, shipbuilders and metalworkers as well as bakers, hairdressers, instrument makers, cooks and florists. The hand plays a very special role in handicrafts, art and music, constituting a prerequisite for the artistic creation processes. The hand’s relation to light and shadow create special possibilities (Fig. 12.6).

Fig. 12.6

Creative hands of a child making shadow images (From Claude Verdan, La main, cet univers. Fondation du Musée de la Main, Lausanne, 1994. © Monique Jacot)

Does creativity reside in the hand or in the brain? Musicians may feel that their hand has learned how to create the music, that it ‘knows what to do’ and that the creative process is actually located in the fingers. One of my patients, a piano teacher, expressed it like this: ‘Doctor, it feels as if my brain is located in my fingers.’ She had been wondering how she could sometimes be thinking of something completely different while her hand, by itself, was playing etudes and waltzes by Chopin.

The Hand, the Brain and the Creative Mind

Creativity is located in the brain, and the hand can ‘play by itself’ because experience and training have shaped motor programmes that remember and control the hand’s movements. We know that an artist’s creativity can still be there even if the hand’s function is severely impaired. One example is Pierre-Auguste Renoir who suffered from a rheumatic disease that severely impeded his gripping function and hand precision. Renoir had to tie the paintbrush to his hand to be able to paint, yet even during periods of severe illness he produced several of his most magnificent paintings. The hand overcame its difficulties despite its very bad condition. Henri Matisse was very impressed by this when he wrote the following about Renoir:

A long lasting suffering – his finger joints were all swollen and severely malformed. – and still he painted his best masterpieces! While his body was fading away his soul seemed to grow stronger and he expressed himself more and more easily [9]

The painter Raoul Dufy was also afflicted with rheumatoid arthritis, but in his case it negatively affected his painting. His capacity to draw and paint gradually became worse as his hand stiffened [9]. But, interestingly enough, medical advances caught up with the disease – effective treatments were developed, and he could again create his art as a direct effect of improved hand function. At age 73, Dufy was severely limited by his illness, but he was one of the first patients to test treatment with cortisone. The result was dramatic; after only a few days of treatment, the mobility and power of his fingers improved. For the first time in several years, he could squeeze out paint from the tubes without help. Once again he could master his tools and create high-quality paintings.

Without treatment, gradual impairment of hand function can negatively affect art. Paul Klee was one of our time’s most talented and special artists who enjoyed constantly creating new pictures in new colours and new constellations. At the age of 40, Klee was affected by a serious connective tissue disease, scleroderma, leading to contractures in the hand and stiffness of the finger joints. As a result his art lost its joyful character, and there was often a shift towards simple pencil drawings [9].

However, there are examples of how a disease affecting the hands can be an advantage and facilitate artistic expression. The legendary violinist Paganini was technically brilliant and was unsurpassed in playing extremely difficult solo pieces and passages. His way of playing had an almost magical power that had an immense impact on his audiences. It was said that Paganini was closely associated with the devil, and for this reason he was not allowed to be buried on holy ground.

Paganini suffered from a very uncommon connective tissue disease, Ehler-Danlos syndrome, characterised by extreme elasticity and increased mobility of the wrist and finger joints. It has been suggested that this contributed to his exceptional technical skills, making it possible for him to play extremely advanced double grips, which astonished listeners and made him famous. The hand’s range was greatly increased. With his left thumb on the middle of the violin’s neck, he could play in the first three positions without changing his grip. Thus, he was able to play very rapid passages with exceptional precision. Paganini played fervently, violently drawing the bow across the strings and playing up and down the scale with admirable speed, the cadenzas flying from his fingers.

As a hand surgeon I have seen many examples of how hand problems critically influence hand creativity. Most cases concerned music students or professional musicians playing both classical music and jazz. Most often their problems were ergonomic and could be resolved by changing body posture and playing technique. However, sometimes it was a disease where anatomical anomalies in the hand made it impossible to reach all of the instrument’s valves and controls. Often the problem can be solved by a slight modification of the instrument’s construction, compensating for limitations in hand function, but many times this is impossible. Dupuytren’s contracture is a pathological condition in the hand characterised by contractures of one or several fingers that cannot be straightened. Most often the contracture appears in the little and ring fingers. One of my patients, a professional flutist, had severe symptoms from his Dupuytren’s disease. He was the principal in a symphony orchestra and had great difficulty managing his work since his little finger didn’t reach out to the most distant key on the flute. His hand function was fairly good, thanks to several surgical procedures over several years, but eventually his hand could not tolerate any more surgery – luckily this coincided with his retirement. Another patient, a young woman, was taking classes to become an alto-violin player but unfortunately developed a moderate form of psoriasis that affected her distal finger joints. She became a physiotherapist, thus becoming doubly skilled as an alto-violin player and physiotherapist.

A hand problem of special interest that I have encountered, especially among flute players, is poor precision and mobility of the right little finger. These patients were unable to individually flex the middle joint of the little finger without simultaneously also flexing the distal joint of the finger. This inability to individually move the little finger’s joints caused major problems in their playing and sometimes forced them to discontinue their ongoing training or switch to another instrument. Intensive exercises were not helpful; the pupil was not able to ‘find the little finger’. The condition resulted in anxiety and self-reproach since the pupil believed that he was not training properly. The phenomenon, sometimes called ‘lazy little finger’, is well known among hand surgeons. It is a matter of a slight anatomical anomaly in the little finger with a lack of one of the two flexor tendons that are present in most of us. In the little finger there are usually two flexor tendons, one ‘deep flexor tendon’, which gives active flexion to the distal joint, and one ‘superficial flexor tendon’, which gives active flexion to the middle joint. Sometimes, as with the ‘lazy little finger’, the superficial flexor tendon is absent, making it impossible to flex the middle joint without also flexing the distal joint. This makes handling the flute’s complicated system of keys difficult, sometimes making a career as a solo player impossible. Many with this problem have been very relieved to learn that it is not a question of poor training but an anatomical anomaly we can do nothing about.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree