21 Degenerative Lumbar Spine Disease

I. Key Points

– Degenerative disease of the spine is a ubiquitous problem and part of the natural aging process. Treatment, surgical or otherwise, is directed at specific symptoms, pathologies, and syndromes.

– Skeletoligamentous disorders are typically the result of intervertebral disc disease, facet disease, or both. Sacroiliac and hip joint pain can also be contributors to back pain.

– Determining the “pain generator” is not always straightforward and requires a synthesis of data from the medical history, physical exam, provocative testing, and imaging.

II. Background

– Degeneration of the lumbar spine is the result of natural aging, environmental insults, and genetic predisposition.

– Degenerative changes may be asymptomatic.3

– Specific disease states, such as rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, can accelerate or alter the pathology and clinical presentations.

– Changes that develop over time include loss of water volume within the nucleus pulposus with loss of disc height, disc bulging, facet joint degeneration, and osteophyte formation across the joints (both the intervertebral discs and facet joints). Eventual loss of motion occurs.

III. Specific Conditions

Radicular Pain

– Signs, symptoms and physical exam

• Diagnosis requires a correlation between the pain distribution and the compressed nerve root identified on imaging.

• Sharp, shooting pain in a given dermatome, but it may be dull or aching as well

• Pain, paresthesias, weakness, and diminished reflexes can be found on exam.

– Workup and neuroimaging

• Diagnostic testing includes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scan (if the offending pathology is suspected to be osseous), or in some cases CT myelogram.

• If there is doubt as to the level or location of the pathology, a test nerve root injection with anesthetic may be diagnostically helpful.

• Classic pathology is a paracentral disc herniation; other possibilities include compression due to foraminal collapse, facet joint overgrowth, or a far lateral disc herniation.

– Treatment

• Treatment of radiculopathy is directed at nerve decompression. This can be done with a laminectomy, laminoforaminotomy, or microdiscetomy.

• In cases where compression is from foraminal collapse due to loss of spinal alignment (e.g., spondylolisthesis or degenerative scoliosis) a fusion with intervertebral height restoration may be indicated.

– Surgical pearls

• During a laminectomy, laminoforaminotomy, or microdiscectomy, care must be taken to avoid excessive facet joint removal. These joints are critical to the stability of the spine, and no more than half of a joint should be removed in a unilateral approach.

• Following surgical decompression scar formation can result in radiculitis or, rarely, arachnoiditis. Minimizing manipulation and nerve root retraction may be helpful.

Neurogenic Claudication

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• Diagnosis is highly dependent on the history. Patients typically complain of unilateral or bilateral leg pain, numbness, and weakness that can be precipitated by standing or walking.

• The ability to walk farther when bending forward (as when pushing a shopping cart) is classic.

• Vascular claudication is suggested when relief occurs with rest without the need to flex at the waist, and must be ruled out by evaluating peripheral pulses (for suspected cases an ankle-brachial index [ABI] may be useful).

– Workup

• Diagnostic testing includes an MRI or CT myelogram to evaluate the size of the lumbar spinal canal and neuroforamina.

– Neuroimaging

• Compression may be due to congenital stenosis, disc bulging, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, facet joint overgrowth, spondylolisthesis, or any combination.

– Treatment

• Surgical intervention is directed at patients who have failed conservative measures, such as epidural injections, and includes decompression with the possibility of an adjunct fusion.

• Standard treatment involves the use of a midline laminectomy with foraminotomies.

• Indirect decompression can be achieved with an interspinous spacer device, which causes focal flexion and stretching of the ligamentum flavum and facet joints.

• Unilateral hemilaminotomy for bilateral decompression is another, less invasive option that preserves more of the skeletoligamentous structures.

– Surgical pearls

• Curved Kerrison rongeurs can be useful to reach out to the distal foramina and should be placed on the caudal and dorsal aspect of the foramen, as this is the least likely location for the exiting nerve root.

• In performing a hemilaminotomy for bilateral decompression, care should be taken to preserve the ipsilateral ligamentum flavum, which will displace the dura ventrally. This reduces the risk of dural injury while work is being performed on the contralateral nerve roots. Ipsilateral decompression can be performed after the opposite side has been decompressed.

Axial Back Pain from Intervertebral Disc Disease (without Deformity)

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• The most classic disc-related mechanical pain syndromes present as pain that worsens with activity and lessens with rest.

• Anterior thigh pain can also be associated with low back pain, as the symptoms may follow a somatotopic pattern.

• Physical examination may reveal pain relief with extension maneuvers and provocation with flexion, although these findings are not universal.

• It is important to eliminate other insidious causes of axial pain, such as infection or malignancies.

– Workup

• MRI to examine the disc and neighboring structures

• CT myelogram when MRI is contraindicated

• Flexion-extension films to rule out spondylolisthesis

– Neuroimaging

• The disc nucleus progressively loses the high signal on T2 (socalled “black disc”) and loss of disc height will also occur.

• Adjacent bony end plates may exhibit high T2 signal, classified as Modic changes.

• Plain x-rays may also reveal degeneration, but dynamic flexion and extension views may be more effective in revealing any instability.

• CT scans may demonstrate osteophytes and are less useful. In marginal cases a provocative discogram can be used to assess the disc’s internal morphology, ability to tolerate the injectate’s pressure, and any symptoms associated with injection.1

– Treatment

• Treatment of disc-related pain remains controversial and requires that patients have failed conservative treatment measures.

• For patients who have intractable symptoms and demonstrable pathology, treatment may be directed at disc removal or the elimination of motion.

• This can be performed with a posterolateral instrumented fusion; anterior, posterior, or transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF, PLIF, TLIF); lateral interbody fusion; extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF), or total disc arthroplasty.

– Surgical pearls

• It is generally believed that if surgical treatment of disc-related pain is warranted, then an interbody fusion is preferable to posterolateral fusion.

• For patients who will undergo disc arthroplasty, care must be taken to exclude those with facet disease, as the posterior joints must continue to function after the operation.

Axial Back Pain from Facet Joint Disease

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• The zygapophyseal joint (facet joint) is a synovial joint that is prone to arthritic changes and is a possible pain generator.

• Pain that worsens with provocative maneuvers such as back extension may be a simple diagnostic clue.

• Facet pain can radiate into the lower extremity, mimicking a painful radiculopathy.

– Workup

• MRI, flexion-extension films, and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) bone scan helpful

• The definitive diagnostic test is an anesthetic or steroid injection (controversy surrounds the relative efficacy of intraarticular versus periarticular joint injections).

• Hip or sacroiliac joint pathology must also be considered as a possible source of “back pain.”

– Neuroimaging

• High T2 signal in the joint as well as increased focal uptake on SPECT bone scans can be valuable predictors.4

– Treatment

• Interventional treatment of isolated facet joint disease is with anesthetic/steroid injections or dorsal ramus rhizolysis.

• In addition, physical therapy and antiinflammatory medications are often helpful.

– Surgical pearls

• Obtain dynamic films to rule out spondylolisthesis.

• Fusion/fixation of the facet joint remains controversial.

Spondylolisthesis

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• Spondylolisthesis may be the result of congenital, traumatic, degenerative, or iatrogenic etiologies.

• A degenerative spondylolisthesis typically affects the L4/L5 level, although any level may become involved.

• A fatigue fracture of the pars followed by progression of slippage may also be classified as a form of degeneration due to chronic mechanical load.

• The clinical syndrome may cause leg pain, back pain, or both.

– Workup

• MRI and flexion-extension films are mandatory.

– Neuroimaging

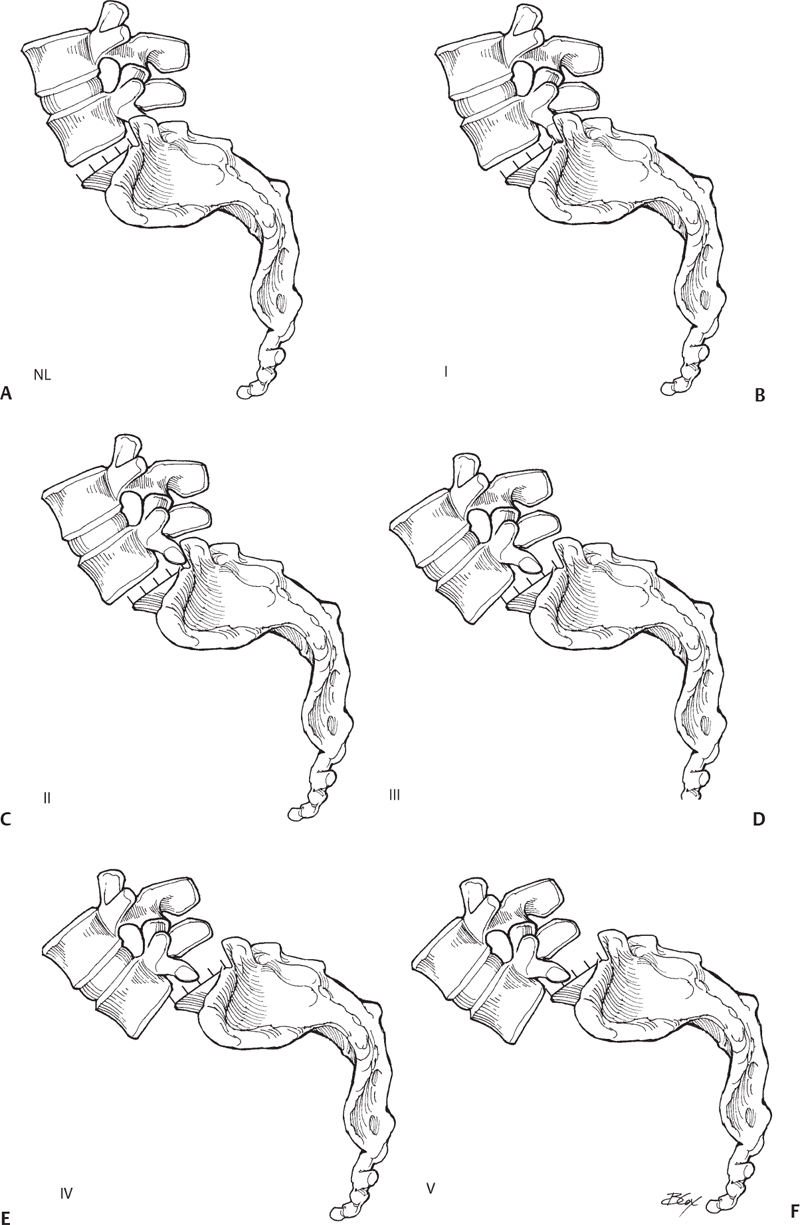

• Diagnostic testing can include MRI imaging to evaluate neural entrapment. Flexion-extension x-rays are mandatory to assess the gross stability of the level, which affects treatment decisions (Fig. 21.1).

– Treatment

• Typically involves decompression and fusion. A common approach is laminectomy for decompression followed by instrumented fusion.

• Controversy exists over the utility of correcting the slippage.

• The use of interbody fusion increases the rate of arthrodesis but poses the threat of higher complication rates.

– Surgical pearls

• High-grade slips where realignment is desired can often be treated more effectively by instrumenting the level above (L4-S1 in a L5/S1 slip) to bring the middle intermediary screw up to a rod connecting the two end screws.

• The exiting nerve root at the slip level is displaced ventrally. Aggressive correction of a high-grade slip can result in foot drop. Close electromyographic (EMG) monitoring for nerve root irritation may allow assessment of the stretch/tension on this structure.

Fig. 21.1 (A–F) Meyerding classification of spondylolisthesis: Normal, Grade I, 0 to 25%; Grade II, 26 to 50%; Grade III, 51 to 75%; Grade IV, 76 to 100%; Grade V, >100% (spondyloptosis).

Degenerative Scoliosis and Kyphosis

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• Evaluation of patients with spinal deformity requires not only a standard physical examination but also an assessment of the patient’s standing and lying postures.

• Any progression of deformity should also be evaluated with serial imaging. The frequent coincidence of hip and sacroiliac joint arthritis and leg length discrepancies needs to be assessed.

• Because this disease entity typically affects older females, an evaluation of bone density may be warranted and the appropriate measures to augment bone density undertaken.

• In addition, assessment of any contributing hip flexion contractures may be necessary.

– Workup

• Diagnostic imaging requires an assessment of neural element integrity (MRI or myelography), disc and facet joint disease, as well as local and global spinal alignment.

– Neuroimaging

• MRI, dynamic x-rays, and CT scanning are essential for preoperative planning.

• Thirty-six inch standing x-rays are mandatory to determine coronal alignment (Cobb angle) and loss of sagittal balance.

– Treatment

• The treatment of this patient population is complicated, requiring significant investment in preoperative planning, surgical intervention, and postoperative care. Critical decision-making factors include:

Source and nature of complaints (pain, reduced activities of daily living (ADLs), neurologic symptoms, abnormal postures, cosmetic concerns)

Source and nature of complaints (pain, reduced activities of daily living (ADLs), neurologic symptoms, abnormal postures, cosmetic concerns)

The degree of deformity and its relative contribution to the patient’s symptoms

The degree of deformity and its relative contribution to the patient’s symptoms

The extent (levels and amount of correction) of the deformity that needs to be treated

The extent (levels and amount of correction) of the deformity that needs to be treated

The amount (quality and number of levels) of fixation needed

The amount (quality and number of levels) of fixation needed

The surgical technique necessary to achieve correction

The surgical technique necessary to achieve correction

Need for fusion adjuncts (osteobiologics, bracing, and bone stimulation)

Need for fusion adjuncts (osteobiologics, bracing, and bone stimulation)

Anesthetic considerations and risks

Anesthetic considerations and risks

Nutrition and metabolic concerns

Nutrition and metabolic concerns

The extent to which rehabilitation will be necessary after surgery

The extent to which rehabilitation will be necessary after surgery

– Surgical pearls

• Careful preoperative planning, including measurements of preop sagittal/coronal imbalance, is essential to achieving good clinical and surgical outcomes.

Common Clinical Questions

1. Lumbar facet joint pain is best treated with:

A. Massage therapy

B. Electrostimulation

C. Joint injections

D. Surgical fusion

2. Causes of spondylolisthesis include all of the following except:

A. Neoplastic

B. Degenerative

C. Traumatic

D. Iatrogenic

3. Studies critical to the evaluation of a spinal deformity include:

A. Blood tests for rheumatoid arthritis

B. Genetic assessment of predilections for deformity

C. SPECT nuclear medicine bone scan

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree