a. One approach has been the development of monoclonal antibodies targeted at various forms of the β-amyloid peptide in an effort to remove these from the brain. This has been shown to cause cognitive improvement in mouse models of AD. Solanezumab is one such antibody targeted at a monomeric (not plaque) form of the β-amyloid peptide with the assumption that the monomeric form is the toxic species. Phase III trials showed that it reduced cognitive decline in mild AD though this trend was not statistically significant. It is, however, thought to be disease modifying. Crenezumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds all forms of β-amyloid. Higher doses showed some slowing of cognitive decline though this did not reach statistical significance. This effect was especially pronounced in those with mild disease. Gantenerumab is a monoclonal antibody designed to bind fibrillar β-amyloid acting to disassemble and degrade amyloid plaques by recruiting microglia and activating phagocytosis. The investigation progressed to phase III but was halted due to a lack of efficacy.

b. MK-8931 is an inhibitor of the β-secretase cleaving enzyme (BACE) 1 and 2. This enzyme acts to prevent the production of β-amyloid which is done through the cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP). This has advanced to phase II/III trials after promising phase I trials showed significantly reduced β-amyloid levels in CSF.

c. Another approach is the development of vaccines in an effort to induce antibody formation against β-amyloid proteins. ACC-001 is a vaccine intended to induce antibodies to beta-sheet conformation regions of β-amyloid. It is currently in phase II trials. CAD106 is another vaccine made up of multiple β-amyloid proteins in an effort to produce a strong antibody response without producing inflammatory T-cell activation. This did well in phase I trials.

d. β-amyloid oligomers are the most toxic forms of amyloid-b and they bind to the cellular prion receptor. This receptor activates an intracellular Fyn kinase which leads to synaptotoxicity. AZD0530 (saracatinib) is an inhibitor of Fyn kinase that has done well in Phase Ib trials.

B. Cognitive remediation. This can be either by pharmacotherapy or with behavioral interventions.

1. Cholinesterase inhibitors. Cholinesterase inhibitors are the mainstay of dementia treatment. The most commonly used and studied is donepezil, but rivastigmine and galantamine are also US FDA approved. These medications work by blocking the metabolism of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft. Acetylcholine is important for attention, memory and neuronal plasticity and there is a decrease in this neurotransmitter in AD. Data have shown that these medications provide small but statistically significant improvements in cognition, behavior, and function. As a class, data support their use in Parkinson’s disease dementia, Lewy body disease (LBD) and vascular dementia. They may worsen symptoms in frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). Side effects include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea and these are the primary reasons cited for stopping these medications. Additional side effects include syncope, bradycardia, and falls.

2. Memantine. The NMDA receptor antagonist memantine is approved for moderate-to-severe dementia. It is thought to be neuroprotective by preventing the pathologic over-activation of the NMDA receptor. It has not been shown to be of benefit in mild AD. There is some evidence that it may be effective in vascular dementia, but there is inconsistent evidence in Parkinson’s, LBD, and FTLD. Our practice is to combine memantine and a cholinesterase inhibitor in moderate-to-severe AD, although there is no good evidence to demonstrate an added benefit.

3. Cognitive intervention. The advantage of cognitive intervention is that it has little side effect compared to pharmacotherapy. However, presently, cognitive interventions are not reimbursed by most insurance companies. Traditionally, cognitive interventions have been divided into:

a. Cognitive enrichment. Which is creating an intellectually stimulating environment for the cognitively at-risk patient. Its main benefits may be related to improved mood and sense of self-worth.

b. Cognitive neurorehabilitation. This involves the use of compensatory mechanism to overcome deficits. The exercises are geared to particular tasks with which the patient may have problems. Both internal and external aids such as diaries and alarm clocks may be used. There is no expectation of improvement in cognition but rather use of compensatory strategies to use the limited cognitive resources available optimally. For these strategies to be useful executive function needs to be relatively intact. As such, cognitive neurorehabilitation appears to work better in AD patients than frontotemporal dementia in which the executive dysfunction is an earlier sign. Various guidelines are available including from American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine.

c. Brain training uses high repetition of a skilled purposeful task to improve cognition via neuroplasticity. Brain training is likely to be useful only at high intensities and with high numbers of repetitions, for this reason batteries of entertaining games used casually at home is unlikely to create the desired effect. The dual n-back training exercise has the greatest weight of evidence behind its efficacy especially for executive function and attention. It is particularly useful in patients with impairment in complex and simple attention, as is the case in traumatic brain injury for example. The exercise should be given daily for a period of weeks for the effects to be useful. No data exist regarding “refreshers” after this initial training period.

C. Treatment of neuropsychiatric comorbidities. These include

1. Depression. The importance of depression and treatment in dementia are several folds:

a. Lifelong depression is a risk factor for the development of dementia. Treatment of depression may reduce the rate of decline in patients with neurodegenerative pathologies. There is some evidence, for example, that the presence of depression predicts conversion from MCI to dementia.

b. Rates of depression are higher in patients with dementia. Approximately 50% of patients with AD have co-occurring depression.

c. Depression in dementia is caused by a combination of physiologic changes in the brain as a result of neurodegeneration but also due to reaction to cognitive decline and loss of independence.

d. Depression can affect attention, memory, motivation, processing speed, and organization. These manifest as real cognitive and executive deficits on neuropsychiatric testing.

e. Pseudo-dementia is a term used to describe a depression that presents with primarily cognitive deficits. It is now thought to be associated with an underlying dementia, and though treatable, it is likely a prodromal phenomenon.

f. Treatment options.

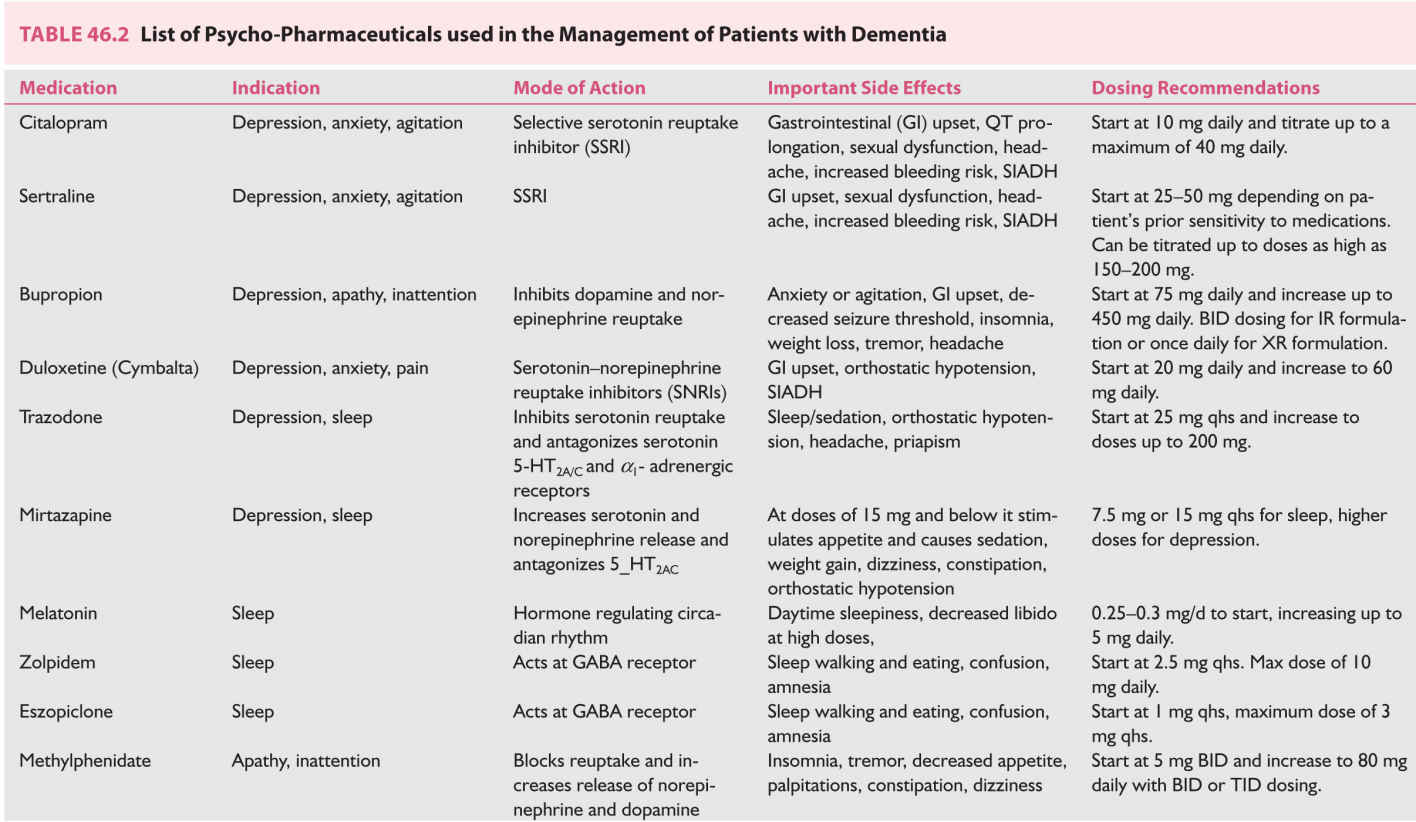

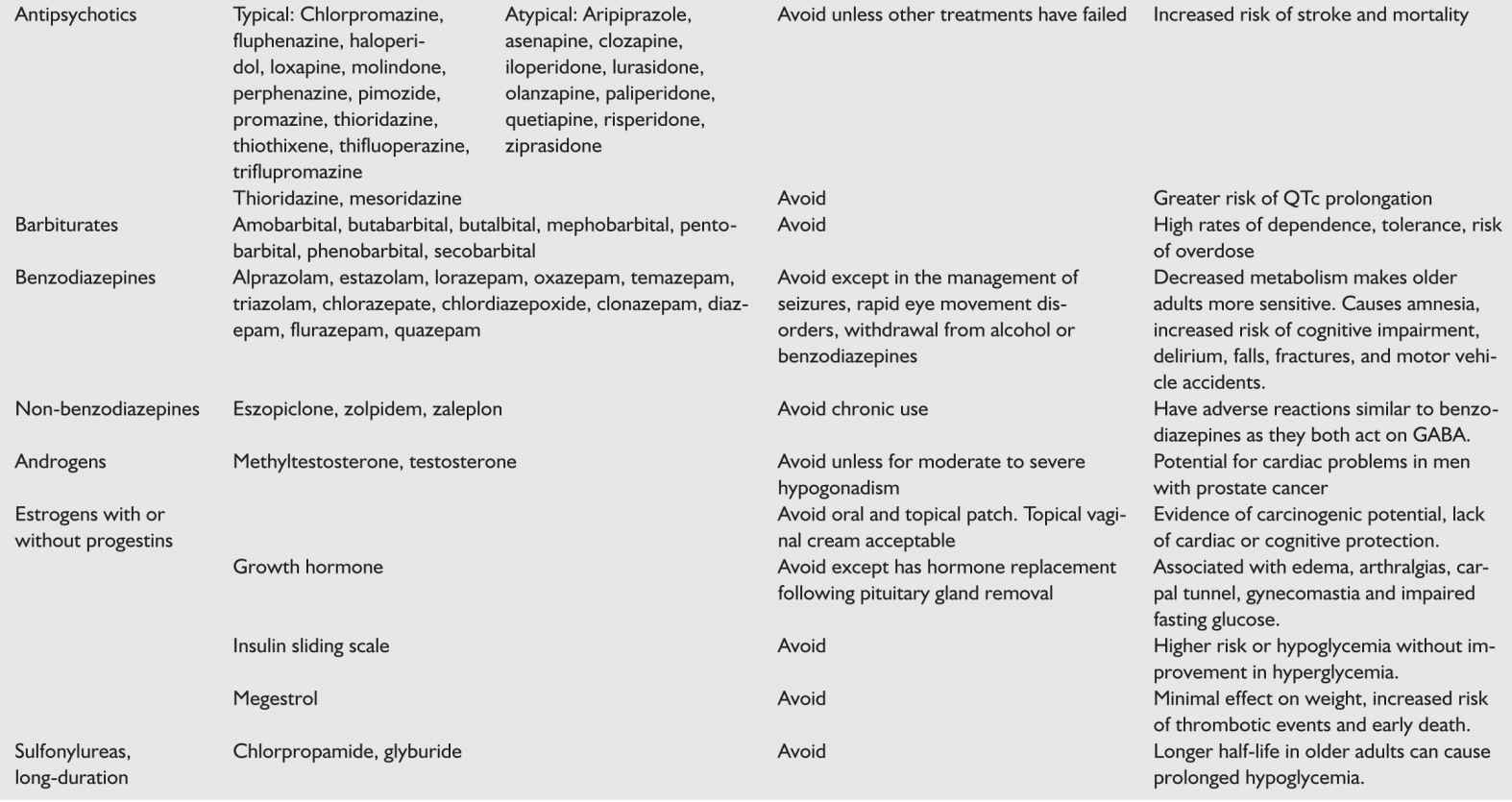

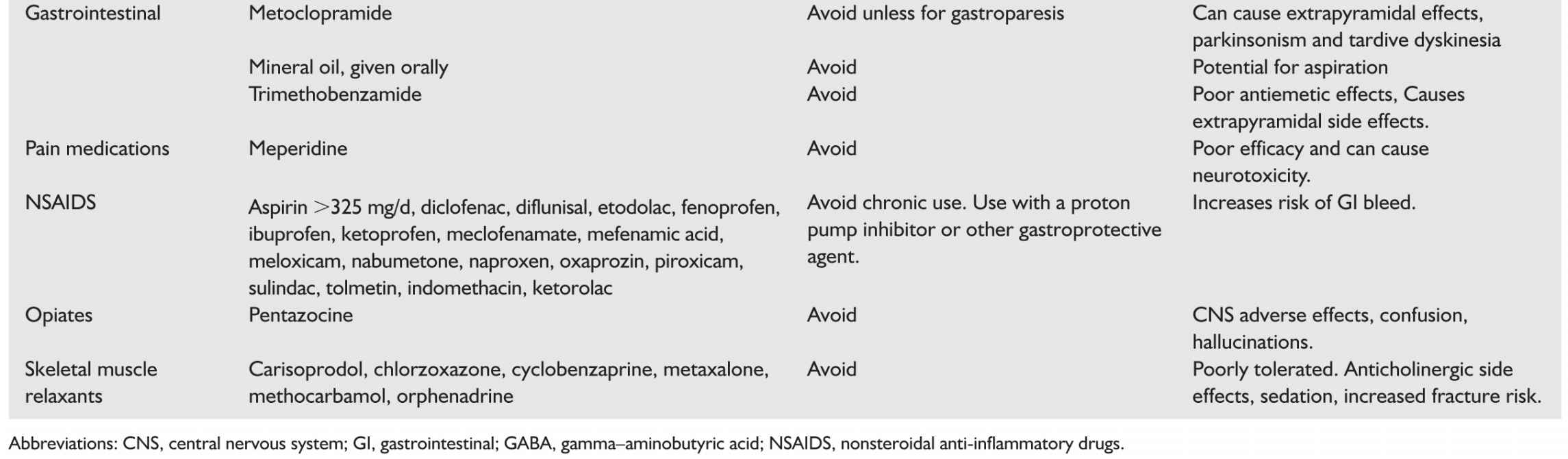

(1) Medications. The choice of treatment will depend on the comorbidities present in the patient. Table 46.2 shows medication options, important side effects, and dosing guidelines.

For patient with comorbid anxiety, the use of nonactivating selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be the initial treatment. Citalopram has a good side-effect profile and is often not activating. Citalopram can increase QT interval. Sertraline is a similarly low-activating antidepressant that is well tolerated. Both Sertraline and Citalopram have been studied in this population to good effect.

Patients with comorbid apathy or loss of motivation may benefit from bupropion, which increases dopamine transmission in the brain. This medication can reduce seizures threshold and is contraindicated in patients with comorbid seizures. This medication has not been specifically studied in this population.

Patient with fatigue or chronic pain and depression may prefer serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as duloxetine. Again, there are no studies specifically in patients with dementia or MCI.

Trazadone can be used as a sleep aid and antidepressant. Its sedating effects last through the night so it is helpful for people that wake frequently. Conversely, patients complain of residual grogginess upon waking. Mirtazepine at a dose of 15 mg PO nightly improves sleep but may increase appetite. This latter side effect may be useful in end stage dementia when anorexia is a major problem. The drawback of both of these medications is that they are weaker antidepressants and have not been studied in patients with dementia.

Avoid tricyclic antidepressants because of potential anticholinergic effects that adversely influence memory.

(2) Meditation. There is some evidence that meditation reduces the activation in the brain and helps with depression.

(3) Talking therapy. Ultimately this is one of the most useful tools in the arsenal of the physician, whether this is done formally (psychiatrist) or informally in the neurologist’s office. There are many therapeutic approaches that have been shown to have efficacy in the treatment of depression including psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and mindfulness-based therapy. Finding the appropriate therapeutic treatment for a particular patient is best done via a referral to a psychiatrist who can assess the psychological, social, and biological factors influencing a patient’s depressive illness along with their goals and preferences to connect them to an appropriate therapist. At a minimum psychoeducation and supportive therapy should be a part of the clinical approach to these patients as they grapple with their limitations and diagnosis.

(4) Transcranial magnetic stimulation. Although data for the use of this modality in dementias is as yet lacking, there are good theoretical reasons to think that the method may hold promise for resistant cases of depression in dementia populations.

2. Anxiety.

a. Anxiety is more common amongst patients with neurodegenerative dementias.

b. Anxiety is caused by both physiologic changes in the brain especially with systems involved in emotional regulation; as well as in reaction to circumstances. The risk of social embarrassment appears to be a strong provoker of anxiety in patients with cognitive problems. Anxiety in neurodegenerative dementias may be physiological, for example due to the loss inhibition of ventromedial frontal lobe or in response to perceived social stigma and feeling of reduced self-efficacy.

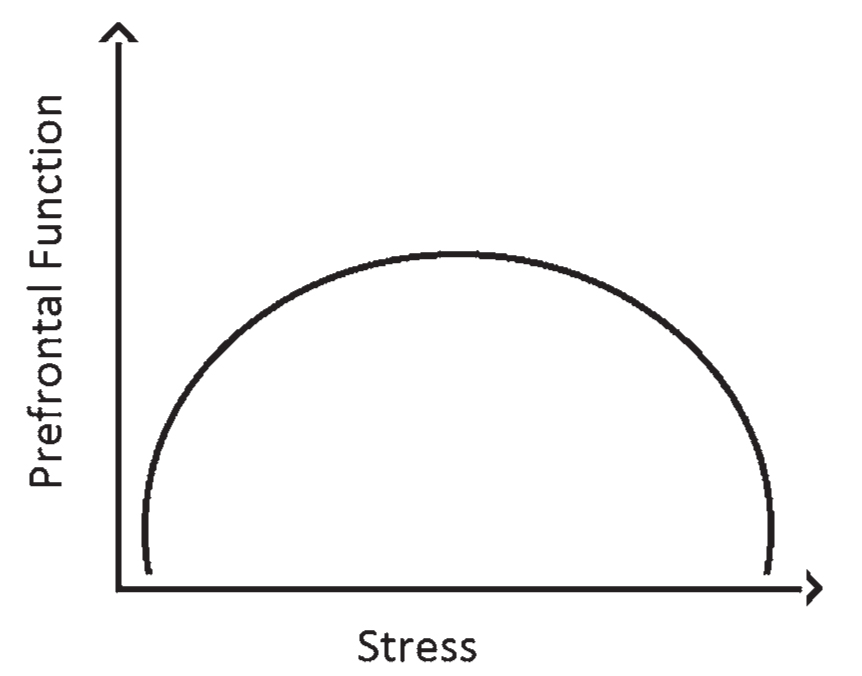

c. High levels of anxiety interfere with prefrontal function: Prefrontal function has an “inverted U curve” relationship with anxiety. In other words at very low and very high levels of anxiety, executive function suffers. Different patients have different needs in terms of how best to maximize their cognition along this curve (Fig. 46.1).

d. Taking a careful history is important in the assessment of anxiety as patients mean different things when they use this term. Often patients will not endorse anxiety if they feel their symptoms are in proportion to, or appropriate for, their situation.

e. Treatment options include.

(1) Medication.

Use of nonactivating SSRIs, primarily Citalopram and Sertraline.

Avoid use of benzodiazepines except for short period of time. Benzodiazepines have immediate amnestic affects, increase risk of delirium, and long-term use increases risk of dementia and MCI converting to dementia.

We have tried Buspirone in the clinic and anecdotally we have not had as much success with this as with SSRIs.

FIGURE 46.1 The inverted U curve relationship between stress/arousal and prefrontal function. At low levels of arousal such as fatigue or ADHD the prefrontal function is poor. In very high levels of stress/anxiety the prefrontal function also suffers. ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

(2) Psychotherapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy may be particularly useful for anxiety in early dementias. The patient’s thought patterns related to reduced self-worth due to reduced cognitive abilities needs to be addressed. It is helpful for patients suffering from social withdrawal and isolation to be encouraged to speak about their predicament and be taught strategies to mitigate social embarrassment.

(3) Other. Adjunctive therapies may include massages, meditation (both directive and mindfulness), and exercise. Exercise has the added benefit that it may slow dementia progression as previously mentioned.

3. Sleep disturbance.

a. Sleep deprivation is a risk factor for dementia especially AD.

b. Sleep deprivation is a risk factor for delirium in neurodegenerative dementias.

c. Loss of sleep architecture may be caused by neurodegenerative changes in the brain.

d. Sleep deprivation worsens cognition.

e. Sleep disorders including nocturnal parasomnias, rapid eye movement (REM) behavior disorder, and daytime hypersomnolence are prodromal features of Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease dementia.

f. Treatment options. Treatments are generally similar to treatments for elderly patients without dementia.

(1) Sleep hygiene. Strict day–night precautions should be observed: during the day, the patient should be exposed to natural light and encouraged to sit out of bed or to be active. Naps should be discouraged. During the night, the room should be darkened, television and other source of artificial light should be turned off, and patient be encouraged to sleep. Avoid caffeine in the afternoon and avoid strenuous exercise or meals right before bed. A bedtime routine and set times may help with better sleep.

(2) Addressing sleep disorders. Untreated obstructive sleep apnea should be addressed. A sleep study may be indicated if the patient appears to dose off during the day, to rule out and treat periodic leg movement or hypnic jerks. REM behavior disorder, often more of a nuisance to the spouse than the patient, is common in Parkinson’s dementia and LBD and may be treated with clonazepam.

(3) Addressing comorbidities. Pain and discomfort can be reasons for lack of sleep and in late dementia may be unexpressed by the patient. Especially in patients with advanced dementia, regular use of acetaminophen for pain should be encouraged if there are no contraindications. When in doubt, the trial of a small dose of an opiate may be indicated.

(4) Medications. Trazadone or mirtazapine are both antidepressants that are frequently and effectively used off label for sleep.

Melatonin: Regular use of melatonin has been shown to reduce delirium risk in patients with dementia. It is not effective as a one-time or as needed sleep aid but rather it has a beneficial effect on circadian rhythm if used nightly for at least 2 weeks. Its potential as a disease modifying agent in AD is under investigation.

Non-benzodiazepines such as zolpidem or eszopiclone can be tried at low doses. Both these medications act on the GABA receptor in a similar fashion to benzodiazepines (BZD). In contrast to BZD these drugs have less anxiolytic properties and are less likely to cause dependence or be abused. They are however associated with amnestic and cognitive side effects.

Avoid benzodiazepines for all the reasons previously discussed. TCA such as doxepin are often used off label for sleep but this should be avoided in patients with dementia due to anticholinergic effects. Diphenhydramine should be avoided for the same reason and patients should be cautioned about its presence in most over-the-counter sleep aids.

4. Fatigue. Fatigue may be related to sleep disturbance or be independent of it. If sleep related then the treatment is often addressing the underlying cause. The use of amantadine is anecdotally helpful but there is no evidence behind its use for this indication. The use of stimulants both amphetamines and modafinil (Table 46.2) is usually not indicated.

5. Apathy. The term apathy refers to a lack of interest or concern as well as a lack of emotional feeling. Apathetic patients initiate very few activities and often ignore personal hygiene and show decreased social engagement. An apathy syndrome occurs when there is damage to the medial prefrontal cortex including the anterior cingulate cortex which is necessary for motor and emotional motivation. This leads to less goal-directed behavior and psychomotor slowing.

This area of the brain is often damaged early in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). AD and other dementia will often affect these brain regions later in the course of the disease as damage progresses to affect more cortical regions.

It is important to note that this is a distinct condition from depression which is also quite commonly co-occurring in dementias. Apathetic patients do not endorse sadness, do not cry, and are not easily upset by people or things in their environment. Clinically differentiating between these two conditions can be challenging.

Estimates of prevalence in AD range from 25% to 90% of individuals. In Parkinson’s disease, dementia estimates are from 20% to 70%. The presence of apathy is associated with poorer cognitive and executive function.

Apathy has been shown to respond to treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and dopaminergic medications such as methylphenidate. However, a 2009 systematic review found insufficient evidence that dementia-related apathy improves with pharmacologic treatment and no subsequent studies have shown otherwise. Nevertheless, we use dopaminergic medications such as bupropion and methylphenidate in our patients and have had some success with these medications. Buproprion has the added benefit of an antidepressant effect if the clinician is also treating depression or is unsure which of these they are treating.

6. Inattention. During delirium, cognitive impersistence may improve with a neuroleptic/antipsychotic. Although the better option in that case is to remove the underlying cause of the delirium. If there are reasons to treat delirium, we prefer to use risperidone due to its relatively high affinity for dopamine receptors and its low affinity for histaminergic or cholinergic receptors which can cause the opposite of the intended treatment effect. It is usually effective at low doses when there is less risk for extrapyramidal or parkinsonian side effects. If delirium has been ruled out as the cause of inattention then dopaminergic medications such as bupropion or stimulants such as methylphenidate can be effective. Often inattention is associated with anxiety and depression and will improve with treatment of these conditions so these should be screened for first.

7. Agitation and aggression. These are the two most problematic and intractable problems in late stage dementias. There is no FDA approved medications for agitation and aggression so all medications discussed below are used off label and a number of them are controversial. There are a number of steps which may be used to improve these symptoms:

a. The first step is to make sure that the aggression is not due to an unmet need. Pain in particular can cause agitation. Scheduled acetaminophen can be tried and when uncertain, a small dose of an opiate may be tried.

b. The triggers for agitation should be addressed. A lack of understanding is often frightening for these patients and can lead to symptoms of paranoia. A common trigger for agitation is suspicion by the patient that something sinister might be going on. To minimize this, the patient should be included in conversation even if they do not understand. Kind prosody should be used when talking to them, and eye contact is important. Minimizing discussions about patients in front of them and working with consistent caregivers as much as possible can also help.

c. Agitation and aggression with a sudden onset or exacerbation can often be the first symptom of a hyperactive delirium. Rule out a urinary tract infection or other metabolic disturbances.

d. If the patient is not on a cholinesterase inhibitor and memantine, then these may be started. The exception is for frontotemporal dementia which may worsen with the introduction of these medications.

e. If the patient is not on an SSRI, then this should also be tried. Note that the effect is going to take weeks to reach an optimum level. Non-activating SSRIs such as citalopram or sertraline might be the medication of choice in this setting. Our clinical experience suggests that often these medications are under dosed in elderly patients perhaps due to tolerability concerns. Starting at a low dose always makes sense but they should be titrated upwards before they are considered to have failed.

f. Mood stabilizers, especially Depakote, may be tried in some cases but often the results are disappointing and there is no evidence that these medications are effective for behavioral symptoms of dementia.

g. Benzodiazepines should only be used as “rescue” medication if the patient’s agitation is severe enough that they are at acute risk of harming themselves or others. Benzodiazepines increase the risk of confusion, falls, and delirium. Benzodiazepine gel formulations are poorly absorbed and are essentially placebos.

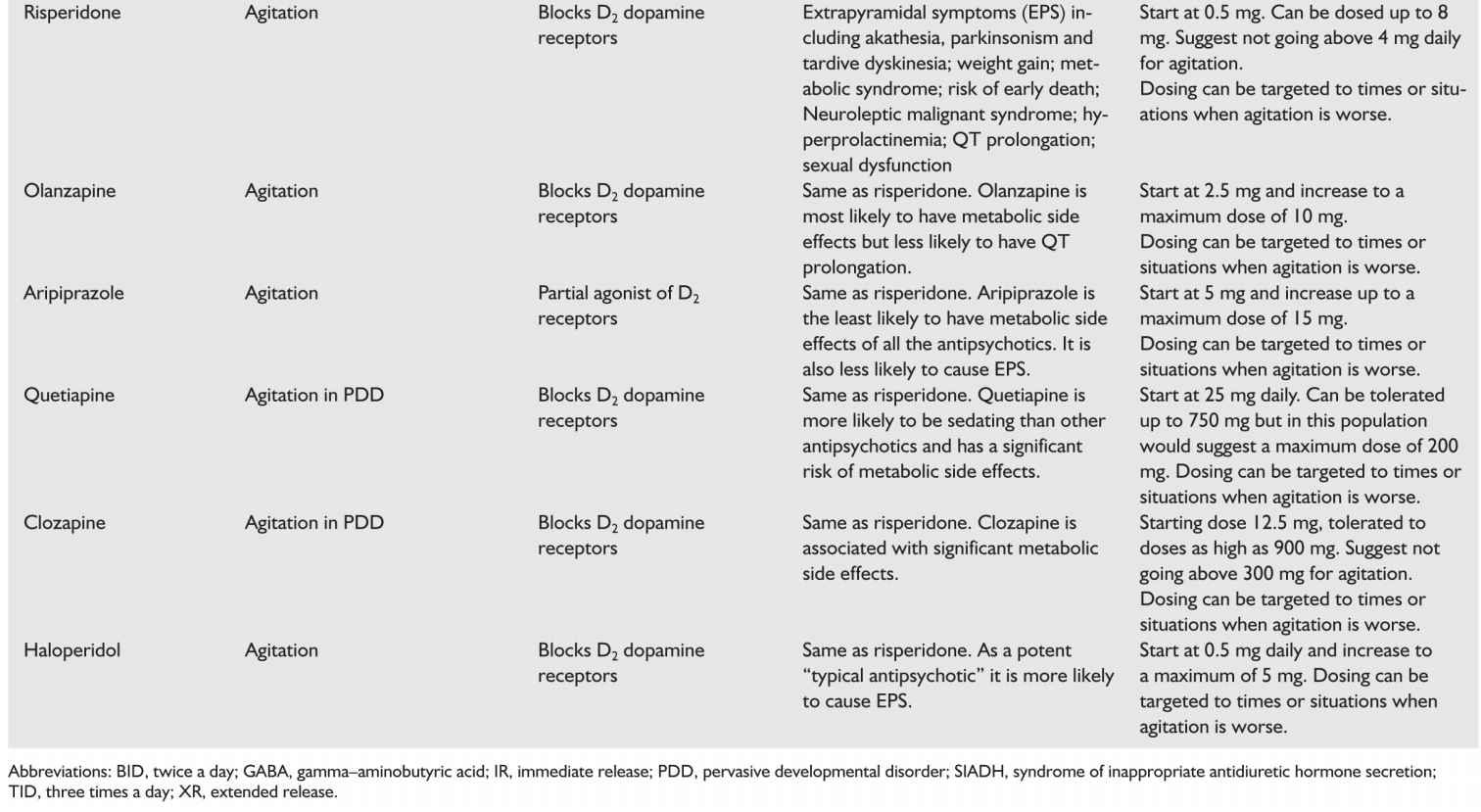

h. Antipsychotics are used off label in as many as 20% to 30% of patients with dementia though their use is controversial. There is no evidence supporting the use of typical antipsychotics in this group with the exception of haloperidol used at low doses for aggression (1.2 to 3.5 mg/day). Meta-analyses of 15 randomized controlled trials of atypical antipsychotics showed efficacy of risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine (in that order). There is insufficient evidence regarding the use of quetiapine though it is often used due to a more favorable side-effect profile. Side effects of antipsychotics are of significant concern and include anticholinergic effects, hyperprolactinemia, prolonged QT interval, orthostatic hypotension, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), weight gain, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, somnolence, sexual dysfunction, seizures, cognitive decline, and increased risk of stroke. Risperidone is the most likely atypical antipsychotic to cause EPS and hyperprolactinemia. Olanzapine is the most likely to cause weight gain, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, orthostatic hypotension, and somnolence. Aripiprazole has a more tolerable side-effect profile. Additionally, both typical and atypical antipsychotics are associated with an increased risk of death which has led the USFDA to give both classes black box warnings regarding their use in patients with dementia. Recent data show that this risk is worse with haloperidol followed by risperidone, then olanzapine, and finally quetiapine. Patients with Lewy body dementia are especially likely to have adverse effects with antipsychotics.

Therefore, antipsychotics should be used sparingly in dementias and a careful risk–benefit analysis should be made and discussed with the patient’s medical decision maker. When patients are severely agitated, we believe the humane thing to do is to treat that agitation, trying more conservative approaches first. Ultimately, despite the risks, there are instances when antipsychotic use is important and can prevent hospitalization and dramatically improve quality of life. When used in Parkinson’s disease dementia and in LBD, only quetiapine and clozapine should be trialed. Quetiapine is preferred as it has the least potential to exacerbate the symptoms of Parkinson’s. If there is evidence of EPS with the start of neuroleptics then they need to be stopped. We recommend only using antipsychotics for which there is evidence of efficacy: risperidone, olanzepine, haloperidol, and aripiprazole.

(1) Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an additional option with significant literature supporting its safety and effectiveness for the treatment of the most agitated and aggressive patients as well as patients with pathologic yelling. It has several obvious benefits: it can be effective quickly and can permit minimal use of potentially harmful medications. Clinicians are often reluctant to consider ECT in this population as it is known to have cognitive side effects. Usually this manifests as amnesia surrounding the procedure. More lasting effects on short- and long-term memory are rare. Studies have failed to show that ECT worsens cognition in patients with dementia. Often, any amnestic effects are far outweighed by an improvement in a patient’s ability to attend to, focus on, and interact with their environment leading to a net positive cognitive effect.

D. Harm minimization.

1. Caregiver training. Caregiver training is an approach that involves problem solving with a family to identify precipitating and modifiable causes of symptoms and working with them to create a specific tailored approach. Several models for this have been studied to good effect for both the patient’s symptoms and for caregiver well-being.

Training may include setting realistic expectation and goals. Also equally as important is to avoid attributing all symptoms to dementia. Intervention is taught to caregivers including reduction of triggers for wandering and aggression. Prompted bladder evacuation can reduce risk of incontinence.

2. Environmental modification. Home safety checks should be done where available to address hazards such as carpets, stairs, and bathrooms. Modifications should be made to reduce fall risk. Adequate lighting may help with orientation and navigation. In facilities clear signs, clocks, and calendars can help to orient a person to the new environment. A consistent daily routine can reduce anxiety.

3. Caregiver support. Over 75% of people with dementia are cared for by family or friends at home. Support includes caregiver respite, day programs, financial and legal advice, and home help. These supportive services may increase the ability of the patient to stay independent for longer.

4. Dementia groups. These provide participants with practical advice, ability to network and mutual support. They are highly recommended.

COUNSELING AND EDUCATION

A. Prognostication. This is one of the most important tasks for the neurologist, as it allows the patient and her family to plan for the future and allows the patient to complete “unfinished business.” By the same token the ability to prognosticate is severely impeded by a lack of reliable data. Most of the data which does exist pertains to AD and VD. There are higher rates of mortality amongst patients with dementia, at least in part due to concomitantly higher vascular risk factors. Aspiration pneumonia is one of the most common causes of death in late stage disease. Life expectancy is often reported to be of the order of 5 years or less from the time of diagnosis. But given the average age of diagnosis in AD is around 75 years, it is likely that the major cause of death in this population is cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease. Improved survival reported in more recent literature is likely related to earlier diagnosis and better cardiovascular risk factor management. The best guide to prognosis is the patient’s progression in the last few years: if decline has been rapid then it is likely to remain so and vice versa. Symptoms begin with impairment in just a couple domains and broaden overtime as the disease progresses.

B. Hereditary risk. The family often likes to know whether they are at increased risk of developing dementias. Family history of late onset dementias in particular late onset AD (>65 years) only confers slightly increased risk of developing the disease. Early-onset dementias however are much more likely to be due to autosomal dominant genetic mutations. In such cases the patient may require genetic testing and counseling. Although no disease modifying medication exists as yet, it is likely that regardless of the mechanism of future treatments, disease modification will be effective only in the earliest stage of the disease. Knowing the genetic status of pre-symptomatic patient might allow them to position themselves better with regards to future clinical trials.

SPECIAL GROUPS

A. Early-onset dementia. Early-onset dementia is dementia that presents before the age of 65. AD is the most common cause of dementia and it is similarly the most common cause of dementia in younger patients followed by vascular disease and FTLD. In patients younger than 35 years of age, most dementias are caused by metabolic disturbances. A large proportion of early-onset AD are caused by autosomal dominant mutations in either the amyloid precursor protein, presenilin-1 or presenilin-2 genes. The presentation is usually similar to later-onset sporadic disease, i.e., patients present with amnesia plus visuospatial problems. However, the incidence of less common neuropsychological types of AD, such as posterior cortical atrophy and executive variant of AD, is relatively higher in the young-onset group compared to the late onset presentation. These rarer neuropsychological presentations are likely to be more rapidly progressive compared to the more common amnesia plus visuospatial subtype (Videos 46.1![]() and 46.2).

and 46.2).

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration refers to a group of degenerative dementias where the neuronal damage is preferentially in the frontal and temporal lobes. The presenting syndromes reflect the functions of the cortical regions within these lobes that are affected first. Two main categories include primary progressive aphasias where damage is primarily in the left hemisphere’s language regions and behavioral variant where damage is primarily in the non-language of the frontal lobes. These illnesses are all likely to have an earlier onset and therefore comprise a larger proportion of early-onset dementias. They are also more highly heritable, about 20% to 40%.

People with Down’s syndrome have a special vulnerability to early-onset AD. This is due to the fact that the gene for amyloid precursor protein is found on chromosome 21 leading to over production of this protein in these individuals and a corresponding increase in accumulation of β-amyloid.

The diagnosis of AD is always difficult but it is especially devastating in younger patients. Because of the increased incidence of hereditary disease it is important to make the correct diagnosis and to refer patient’s to genetic counseling to know if other family members are at risk. Additionally it is often important to refer patients and their families to counselors and psychiatry to process their grief surrounding the diagnosis. Community support groups can also be very helpful for patients and families.

B. Asymptomatic patients with strong genetic risk. This special group of patients have unique needs. They should be referred to genetic counseling and to psychiatry. Many will ask about prevention and ways to delay presentation of the disease. While it is not clear to what extent this can be done the psychological benefits to patients of feeling like they can be proactive is significant so education about risk factor minimization should be offered. But they should also be cautioned about the limited benefits of many of the products marketed with high promise. These patients are also often highly motivated to participate in clinical trials if they are available in your region.

C. Anosognosia. Anosognosia is an unawareness of a neurological deficit. It is a problem in dementia patients because their compliance with safety measures and treatments will be affected. There are three reasons why a dementia patient may not accept her diagnosis:

1. Denial. The main reason people deny having cognitive problems is that their self-worth is in some ways tied in with their mental capacity. Counseling that addresses feeling of self-worth will help with denial.

2. Loss of self-monitoring mechanism. Self-monitoring is a cortical function. Often this skill can become impaired or lost. The patient may be helped by education about the high prevalence of anosognosia in dementia populations. It is also useful to go through the cognitive test results to convince the patient of the fact of their cognitive decline. Working with care givers to understand and accommodate for this is also important.

3. The patient does not have the intellectual capacity to understand the disease. This is usually in end stage disease and the patient should be approached with kindness and understanding.

D. Difficult diagnosis. Some people may not be diagnosed even after genetic testing, lumbar puncture (LP) and positron emission tomography (PET) scanning. The strategy may be to repeat neuropsychological testing in 6 months or a year. If rapidly progressive and no diagnosis then brain biopsy may be considered.

Key Points

• Management of vascular risk factors, especially hypertension currently shows the most promise for disease modification in AD and vascular cognitive impairment (VCI).

• The main treatments are currently cholinesterase inhibitors, which have been shown to be of modest benefit in most dementia’s with the exception of FTLD, and memantine, which has been shown to be beneficial in moderate-to-severe AD or VCI.

• Screen for and treat comorbid depression and anxiety. Depression often presents similar to dementia and both conditions worsen cognitive function.

• Harm reduction is key: treat and take measures to avoid delirium, address polypharmacy and minimize use of medications such as benzodiazepines medications with anticholinergic effects as they worsen cognition.

• In advanced dementia behavioral symptoms can be a challenge for clinicians and we recommend an approach focused on quality of life and risk benefit analysis.

• Early-onset dementias, presenting prior to age 65, are more likely to be heritable so correct diagnosis and genetic testing and counseling are important for these patients and their families.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree