Chapter 1 Diagnosis and Treatment of Spinal Pain

Classifications of spinal pain

Low back pain (LBP) is defined as pain and discomfort that are localized below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds with or without leg pain. LBP is further defined according to the duration of an episode: acute, less than 6 weeks; subacute, between 6 and 12 weeks; chronic, 12 weeks or more (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Classification of Low Back Pain According to Duration of Episode

| Duration (Weeks) | Classification and Comments |

|---|---|

| <6 | |

| 6-12 | Subacute |

| >12 |

Nonspecific low back pain is defined as low back pain that is not attributed to recognizable, known, specific pathology (e.g., infection, tumor, osteoporosis, ankylosing spondylitis, fracture, inflammatory process, radicular syndrome, or cauda equina syndrome) (Box 1.1).

BOX 1.1 Three Categories (Or Diagnostic Triage) of Acute Low Back Pain

Chronic pain is defined as pain that:

The four diagnostic categories of LBP according to ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th revision) [1] in the absence of symptoms that suggest serious underlying disease (e.g., cancer, cauda equina syndrome, significant or progressive neurologic deficit, or other systemic illness) are as follows:

Table 1.2 Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain

| Diagnosis | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Recommended | Not Recommended | |

| D1: Undertake diagnostic triage (serious spinal pathology, nerve root pain/radicular pain, or nonspecific low back pain), consisting of appropriate history and physical examination, at the first assessment. | T1: Give adequate information and reassure the patient. | T2: Prescription of bed rest as a treatment. |

| D2: Assess for psychosocial risk factors (yellow flags; see Table 1.3) and review them in detail if there is no improvement. | T3: Advise the patient to stay active and to continue normal daily activities, including work if possible. | T4: Specific exercises for acute low back pain. |

| D3: Diagnostic imaging tests (including radiographs, CT, and MRI) are not routinely indicated for acute low back pain. | T5: Prescribe medication, if necessary, for pain relief. | T6: Epidural corticosteroid injections for acute nonspecific low back pain. |

| D4: Reassess the patient whose symptoms fail to resolve. | T7: Consider spinal manipulation for patients who are failing to return to normal activities.T13: Consider multidisciplinary treatment programs in occupational settings for workers on sick leave for more than 4-8 weeks. | T8: “Back schools” for treatment of acute low back pain.T9: Behavioral therapy for treatment of acute low back pain.T10: Traction.T11: Massage as a treatment for acute nonspecific low back pain.T12: Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) as a treatment for acute nonspecific low back pain. |

Diagnostic triage of acute LBP consists of the following conditions (see Box 1.1):

Red flags in the diagnosis of LBP are signs that a serious spinal pathology may be the cause of the LBP; they are listed in Table 1.3:

Table 1.3 Red and Yellow Flags in Diagnosis of Low Back Pain

| Red flags (signs of serious pathology) | |

| Yellow flags (psychosocial risk factors) | Inappropriate attitudes and benefits about back pain (e.g., belief that back pain is potentially harmful or severely disabling, high expectations of passive treatments rather than belief that active participation will help) |

Psychosocial yellow flags are patient factors that increase the risk for development or perpetuation of chronic pain and long-term disability (including work loss associated with LBP); examples are listed in Table 1.3. Identification of yellow flags should lead to appropriate cognitive and behavioral management.

Considerations for diagnosis

Advanced imaging studies should be performed only for the patient with the following findings:

Epidemiology of low back pain

Risk factors for LBP are poorly understood. The most frequently reported are as follows:

Outcomes

The aims of treatment for acute LBP are as follows:

Relevant outcomes for acute LBP are as follows:

Intervention-specific outcomes may also be relevant; examples are as follows:

Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain in Primary Care

The aims of treatment for acute LBP in primary care are to:

A General Assessment of Patients Reporting Low Back Pain

Psychosocial Factors to consider include the following:

Relevant Medical History

Key elements of the patient’s medical history when symptoms of spinal pain are present (Boxes 1.2 to 1.4 and Table 1.4) are as follows:

BOX 1.2 Waddell Embellishment Tests That Indicate Nonorganic Pathology For Low Back Pain

Modified from Waddell G: 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences: A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine 1987;12:632-644.

Tests

BOX 1.4 Preoperative Psychological Screening Risk Factors For Poor Surgical Outcome

MMPI, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory.

Table 1.4 History Taking for Spinal Pain

| Question/Subject | Answer | Diagnostic Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Young | Disc injuries, spondylolisthesis |

| Middle age | Sprain/strain, herniated disc, degenerative disc disease | |

| Elderly | Spinal stenosis, herniated disc, degenerative disc disease, arthritis | |

| Pain: | ||

| Character | Radiating (shooting) | Radiculopathy (herniated disc, spondylosis) |

| Diffuse, dull, nonradiating | Cervical or lumbar strain (soft tissue injury) | |

| Location | Unilateral vs. bilateral | |

| Neck | Cervical spondylosis, neck sprain, muscle strain | |

| Arm (± radiation) | Cervical spondylosis (± myelopathy), neck sprain, muscle strain | |

| Lower back | Degenerative disc disease, back sprain, muscle strain | |

| Legs (± radiation) | Herniated disc, spinal stenosis | |

| Occurrence | Night pain | Tumor |

| With activity | Usually mechanical etiology | |

| Alleviated by | Arm elevation | Herniated cervical disc |

| Sitting down | Spinal stenosis (stenosis relieved) | |

| Exacerbated by | Back extension | Spinal stenosis (e.g., going down stairs) |

| Trauma | Motor vehicle accident (seatbelt?) | Cervical strain (whiplash), cervical fractures, ligamentous injury |

| Activity | Sports (stretching injury) | “Burners/stingers” (especially in football) |

| Neurologic symptoms | Pain, numbness, tingling | Radiculopathy, neuropathy |

| Spasticity, clumsiness | Myelopathy | |

| Bowel or bladder symptoms | Cauda equina syndrome | |

| Systemic complaints | Fever, weight loss | Infection, tumor |

Physical Examination

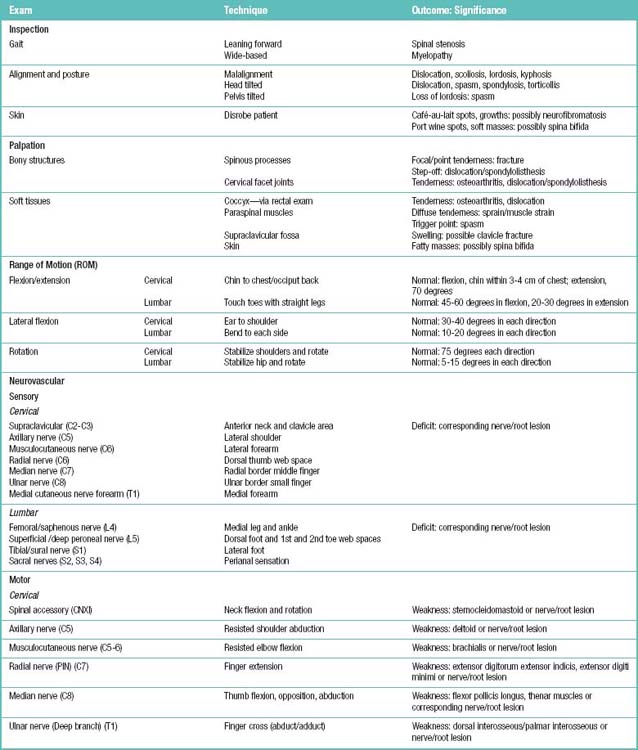

A physical examination for patients with symptoms of spinal pain would include palpation for spinal tenderness, neuromuscular testing, and the straight-leg raise (SLR) test. Table 1.5 summarizes the examination, techniques, and their clinical application in the patient with a complaint of low back pain.

Neuromuscular testing should be performed to evaluate the following aspects:

Significant or progressive neuromotor deficit requires surgical consultation.

Related anatomy and physiology

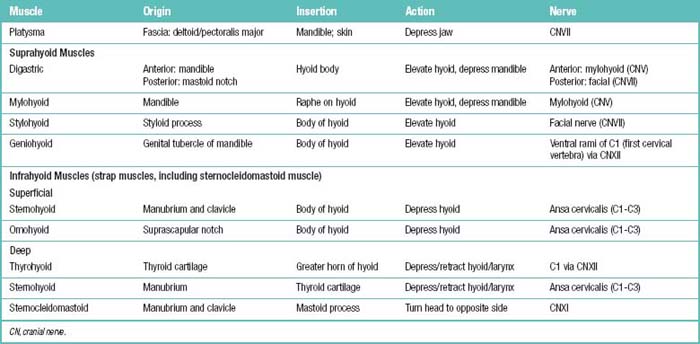

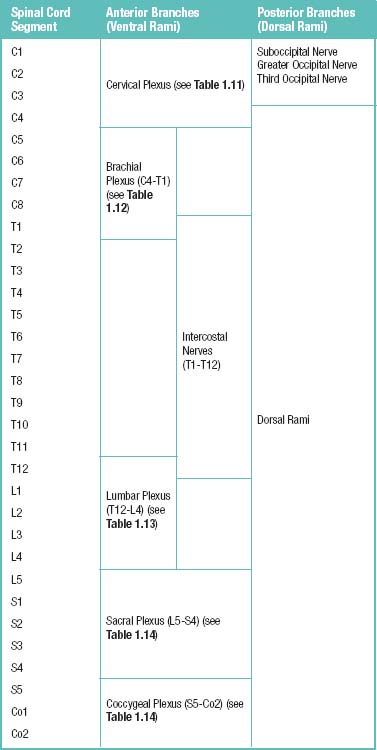

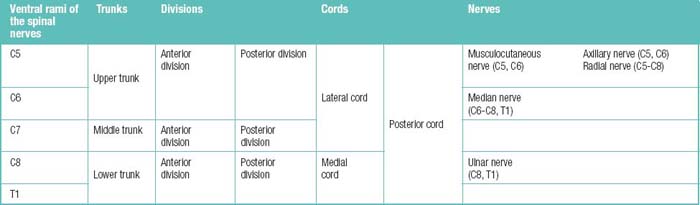

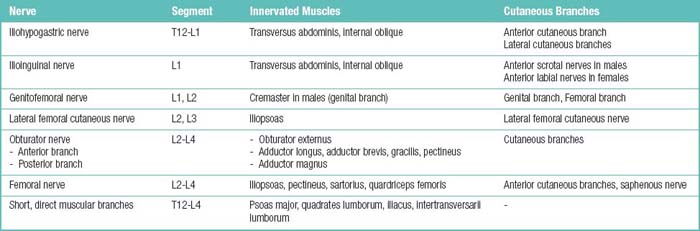

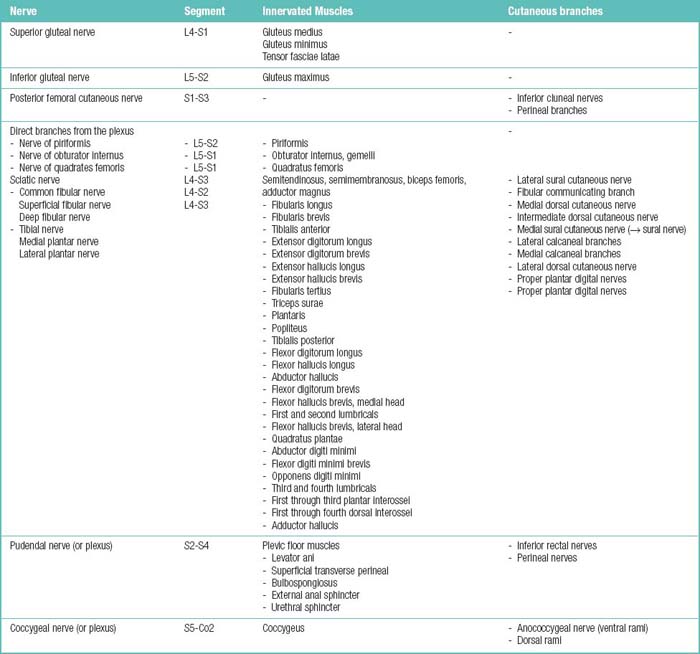

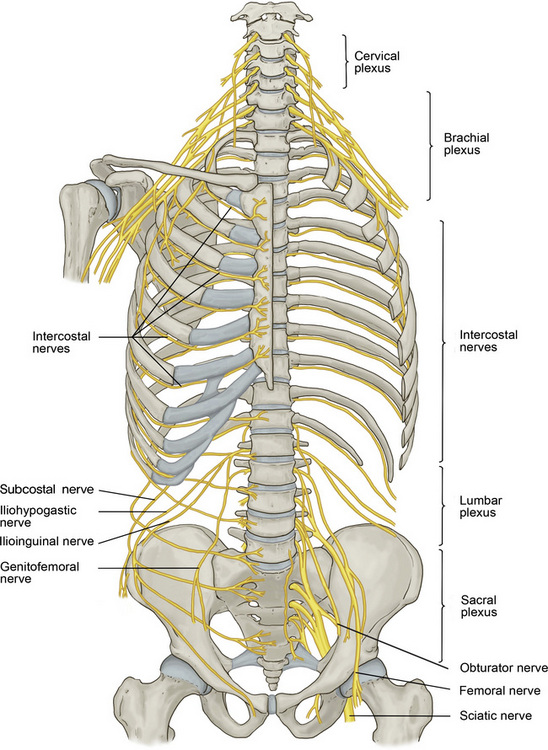

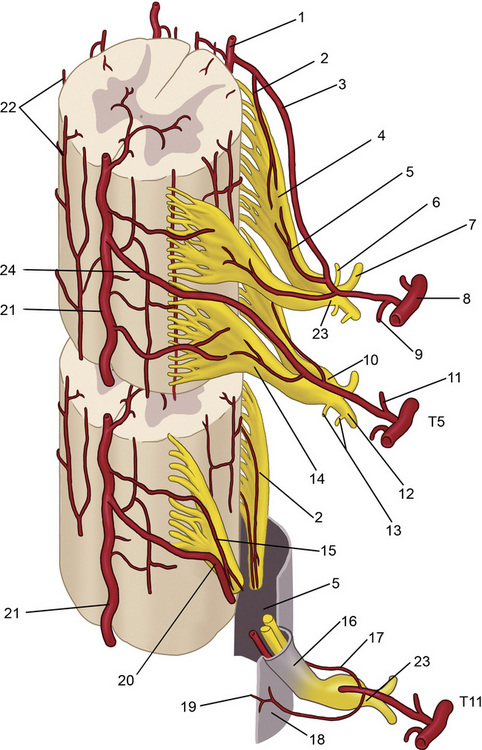

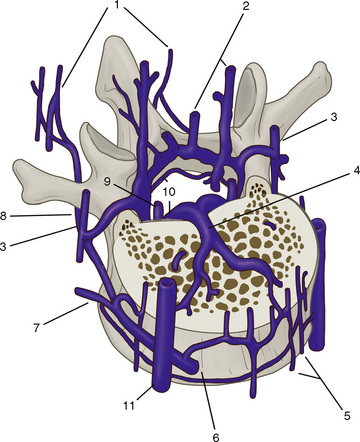

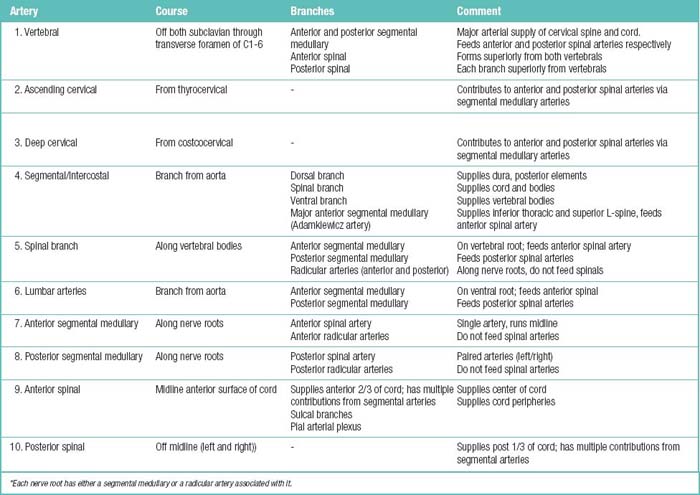

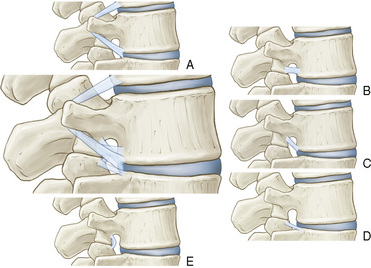

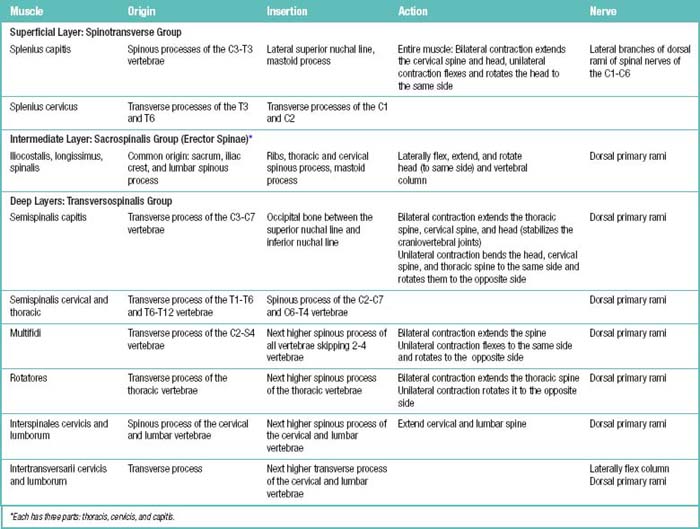

The spinal muscles on the neck and back are described in Tables 1.6 through 1.9. The spinal nerves are described in Tables 1.10 through 1.15 and shown in Figures 1-1 and 1-2. The spinal blood supply is shown in Figures 1-3 and 1-4 and described in Table 1.16. The intervertebral foraminal ligaments of the lumbar spine are shown in Figure 1-5.

Table 1.7 Posterior Neck Muscles (Suboccipital Triangle): Origins, Insertions, Actions, and Related Innervations

Table 1.8 Superficial (Extrinsic) Posterior Neck and Back Neck Muscles: Origins, Insertions, Actions, and Related Innervations

Table 1.9 Deep (Intrinsic) Posterior Neck and Back Neck Muscles: Origins, Insertions, Actions, and Related Innervations

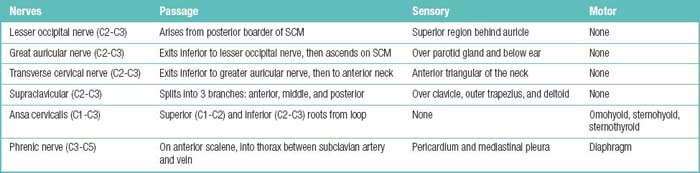

Table 1.11 Cervical Plexus (C1-C4 Ventral Rami) behind Internal Jugular Vein and Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) Muscles

Table 1.15 Spinal Nerve Branches and the Territories They Supply

| Spinal nerve branch | Motor visceromotor territory | Sensory territory |

|---|---|---|

| Ventral ramus | All somatic muscles except for the intrinsic back muscles | Skin of the lateral and naterior trunk wall and of the upper and lower limbs |

| Dorsal ramus | Intrinsic back muscles | Posterior skin of the head and neck, skin of the back and buttock |

| Menigeal ramus | – | Spinal meniges, ligaments of the spinal column, capsules of the facet joints |

| White ramus communicans | Carries preganglionic fibers from the spinal nerve to the sympathetic trunk (‘White’ because the preganglionic fibers are myelinated) | – |

| Gray ramus communicans* | Carrries postganglionic fibers from the sympahetic trunk back to the spinal nerve (‘Gray’ because the fibers are unmyelinated) | – |

* Strictly speaking, the gray ramus communicans is not a spinal nerve branch but a branch passing from the sympathetic trunk to the spinal nerve.

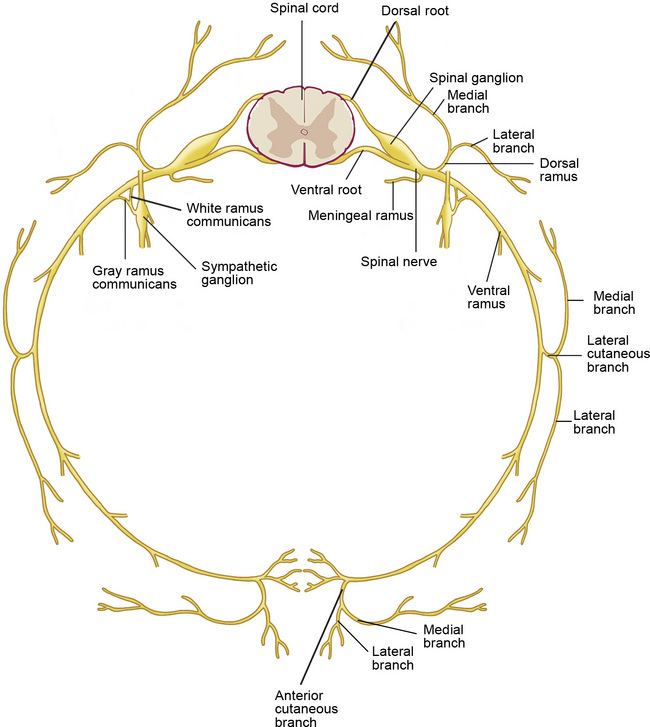

Figure 1–2 Branches of the spinal nerves. Formed by the union of the dorsal (sensory) and ventral (motor) roots, the approximately 1 cm–long spinal nerve courses through the intervertebral foramen and divides into five branches after exiting the vertebral canal (see Table 1.15).

Imaging studies

The indications for and advantages of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) in the evaluation of low back pain are summarized in Table 1.17.

Table 1.17 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT): Indications and Advantages in the Evaluation of Low Back Pain

| MRI | CT | |

|---|---|---|

| Indications | ||

| Major or progressive neurologic deficit (e.g., foot drop or functionally limiting weakness such as hip flexion or knee extension) | Yes | Yes |

| Cauda equina syndrome (loss of bowel or bladder control or saddle anesthesia) | Yes | Yes |

| Progressively severe pain and debility despite conservative therapy | Yes | Yes |

| Severe or incapacitating back or leg pain (e.g., requiring hospitalization, precluding walking, or significantly limiting the activities of daily living) | Yes | Yes |

| Clinical or radiologic suspicion of neoplasm (e.g., lytic or sclerotic lesion on plain radiographs, history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, or systemic symptoms) | Yes | Yes |

| Clinical or radiologic suspicion of infection (e.g., end plate destruction on plain radiographs, history of drug or alcohol abuse, or systemic symptoms) | Yes | No |

| Severe low back pain or radicular pain that is unresponsive to conservative therapy and with indications for surgical intervention | Yes | No |

| Bone tumors (to detect or characterize) | No | Yes |

| Advantages | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|