30 Direct Fixation of Odontoid Fractures

I. Key Points

– Odontoid screw fixation is suitable for acute type II odontoid fractures, which represent 60% of all dens fractures.1

– Rigid immobilization alone has been associated with nonunion in over 50% of cases in many series. Risk factors for nonunion include age greater than 50, displacement more than 6 mm, angulation, and smoking history.1

– Odontoid screws allow for direct fixation of the fracture fragments and have been reported to result in successful stabilization in 80 to 90% of cases.2

II. Indications

– Type II or shallow type III fractures that are acute or subacute

– Contraindications include pathologic fracture, injuries with associated rupture of the transverse atlantal ligament, chronic nonunion of odontoid (fractures present for more than 3 to 6 months), and comminuted fractures.

– Contraindications include severe osteoporosis, irreducible fractures, barrel chest, and thoracic kyphosis where the trajectory for a screw is not possible.

III. Technique

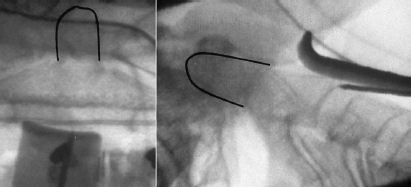

– Intraoperative fluoroscopy is essential to these procedures and should be performed in the anteroposterior (AP) and lateral planes (i.e., use two C-arms, Fig. 30.1).

– Place patient supine in halter traction or Gardner-Wells tongs.

– A bite block (cork) is useful for obtaining the AP image.

– Proper patient positioning with fracture reduction and extension of the neck to allow for proper screw trajectory is the most important aspect of the procedure.

– A transverse incision at C5-C6 provides the proper trajectory.

– Dissection is carried down to precervical fascia exactly as in approach for anterior cervical decompression.

– Medial-lateral retractors are placed under longus at C5 and blunt dissection is carried up to C2-C3 disc space.

– A cephalad retractor is used to protect the esophagus.

– Two general techniques may be used to place the screw: a cannulated screw system that allows the screw to be placed over a K-wire, or a non-cannulated screw that is placed directly down the path of the drill.

– The author prefers to use a non-cannulated system with specialized retractors and drill guides that allow for optimal position of the screw in the dens (Fig. 30.1).

– The trajectory is chosen so that the screw enters the C2 body in the anterior portion of the C2-C3 disc and not along the anterior border of the body of C2.

– Once the entry point is chosen, three steps remain: drill, tap, screw.

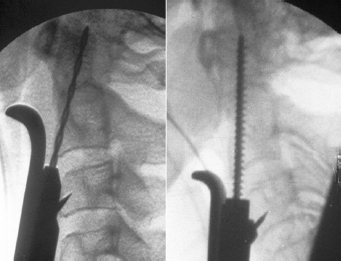

– Drilling is performed with fluoroscopic imaging to ensure that the path of the screw is acceptable and that the distal fracture fragment is not displaced cephalad during the drilling.

– The drill should engage the cortex at the distal tip of the dens to allow the screw to penetrate and lag the two fragments of the dens together (Fig. 30.2). It is this distal cortex that provides the strength for the fixation. If not engaged, the screw can back out and fixation will fail.

– The entire length of the screw trajectory is tapped, including the distal cortex.

– Either one or two screws can be used. The first screw should be a partially threaded or lag screw that will draw the fragments together once the distal cortex is engaged. The second screw is fully threaded.

– Once the screws are placed, the retractors are carefully removed, the wound irrigated, and the incision closed like that for an anterior cervical decompression and fusion. Meticulous hemostasis is performed prior to closure to prevent a retropharyngeal hematoma.

Fig. 30.1 Simultaneous AP and lateral fluoroscopy with retractors in place and K-wire pointing to the entry point for the screw. (Reproduced with permission of Springer from Dailey et al 2010.)1

Fig. 30.2 Lateral fluoroscopy showing the correct position of the tip of the drill (left) and tap (right) so that the screw will engage the distal cortex of the dens. (Reproduced with permission of Springer from Dailey et al 2010.)1

IV. Complications

– Nonunion. This can be treated with a posterior C1-C2 arthrodesis.

– Screw back-out

– Screw breakage. Rare with non-cannulated 3.5 mm screws.

– Dysphagia and hoarseness. In the elderly population, patients may temporarily need a feeding tube due to dysphagia up to 25% of the time.3

– Aspiration pneumonia

– Retropharyngeal hematoma

V. Postoperative Care

– Mobilize patients immediately, particularly elderly patients.

– Observe for signs of dysphagia and aspiration, particularly in older patients. Advance diet with caution.

– A collar may provide some additional support, particularly in osteopenic patients. Biomechanical studies show that the odontoid is restored to half its intact strength with fixation using either one or two screws.

– Patients should be followed with serial x-rays for at least one year, including flexion and extension films at 3, 6, and 12 months.

VI. Outcomes

– The largest series in the literature report fusion rates of around 90% in all patients regardless of age (Fig. 30.3).2 Other studies have reported similar rates of fusion.4

– There has generally been no reported difference in fusion rates if one versus two screws are used.1,2

– Two screws may lead to a better stabilization rate in patients over 70, as a recent series reports a 96% stability rate with two screws, but only a 56% rate with the use of one screw.3

VII. Surgical Pearls

– Preoperative planning and careful patient selection are key to obtaining success with an odontoid screw.

– Proper positioning is crucial to successful screw placement.

– Always make sure that the screw tip engages the distal cortex of the dens.

– Counsel patients and their families that if the procedure cannot be completed, a posterior C1-C2 fusion will provide a suitable alternative or “salvage” procedure.

– So-called anterior oblique dens fractures where the fracture line runs posterior-superior to anterior-inferior are difficult to realign with an odontoid screw, and higher failure rates have been reported with this procedure.

Fig. 30.3 Sagittal computed tomography with odontoid screw in position, demonstrating healing of fracture at 1 year after surgery. (Reproduced with permission of Springer from Dailey et al 2010.)1

Common Clinical Questions

1. Contraindications to odontoid screw placement include all of the following except:

A. Pathologic fracture

B. Chronic nonunion

C. Type II fracture with associated stable C1 fracture

D. Type I fracture with associated atlantooccipital dislocation

2. The most common cervical spine fracture in the population over age 65 is:

A. Hangman’s fracture

B. Type II odontoid fracture

C. Type III odontoid fracture

D. Type I odontoid fracture

3. What is the most common immediate postoperative complication following odontoid screw fixation in patients over age 65?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree