Diseases of Myelin

Juan C. Troncoso

White matter owes its color to the abundance of myelin, a complex lipoprotein that covers and insulates axons. Myelin is produced by oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system and by Schwann cells in peripheral nerves. Myelin is incorporated onto the cell membrane of oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells, which then wrap around the axons, forming multiple concentric layers. In this way, each oligodendrocyte or Schwann cell sustains the myelin sheath of an axonal internode. Whereas oligodendrocytes provide myelin for several axons, the Schwann cell covers a single internode in a single axon.

Demyelinating disorders occur when the central or peripheral myelin and their respective sustaining cells become targets of immune-mediated processes, metabolic derangements, infections, or toxins. In this chapter, we focus on diseases of the central white matter, and in particular, multiple sclerosis, which is the most common of the demyelinating diseases examined at forensic institutions.

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

Clinical Presentation

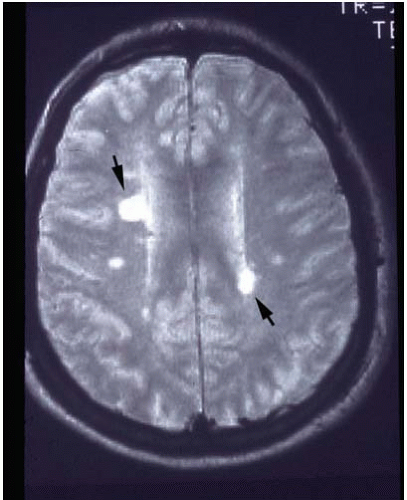

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a multifocal, inflammatory, demyelinating, and axonal disease of the central nervous system with variable clinical presentation.1 The majority of patients with MS (85%) have a chronic relapsing and remitting course, characterized by well-defined attacks of neurologic dysfunction followed by recovery. After a number of years, however, many of these patients experience a steadier decline in neurologic function. A small proportion (10%) of patients with MS experience steady decline from the onset of the disease, without remissions.2 The onset of the disease is usually in young adults, and the clinical manifestations may include any sign or symptom arising from lesions of the spinal cord, brain, or optic nerves. The optic nerve is an extension of the brain, thus its myelin is produced by oligodendrocytes and is vulnerable in MS. Paralysis, sensory abnormalities, lack of coordination, and visual deficits are common initial manifestations. As the disease progresses, behavioral and cognitive deficits may develop. Not uncommonly, the first manifestation of MS is total or partial loss of vision in one eye, which is the clinical expression of inflammation and demyelination of an optic nerve, a pathologic process known as optic neuritis. Neuroimaging, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in particular, has become a useful tool for making the diagnosis of MS and tracking its progression (Fig. 19.1). Imaging can show the existence of multiple white matter lesions even when clinical assessment points to a single one. Furthermore, imaging teaches us that many of the lesions of multiple sclerosis could be silent.

Pathologic Features

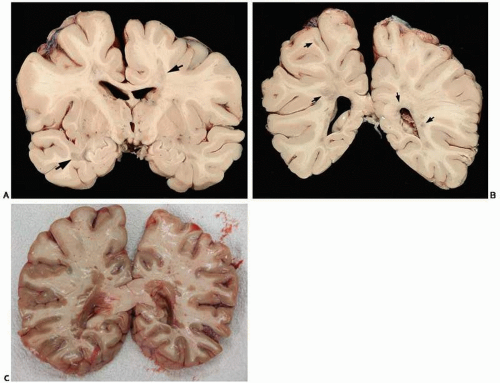

For proper assessment of the lesions of MS, it is important to examine both the brain and spinal cord. External examination of the brain should include a thorough inspection of optic nerves, chiasm, and tracts for atrophy or discoloration. To facilitate this inspection, it is advisable to compare, side by side, the optic structures of the brain from a person with expected MS with a control brain matched by age and weight. On coronal sections, foci of gray discoloration are present throughout the cerebral, brainstem, and cerebellar white matter (Fig. 19.2). These lesions are foci of demyelination, also known as plaques, and are typically seen around the ventricular system. However, the plaques of demyelination are not necessarily confined to the white matter

and may also involve cortical gray matter, the thalamus, or the basal ganglia. Usually when there is a history of MS, the plaques of demyelination are evident on gross examination; however, there are exceptions in which the identification of the lesions requires microscopic examination.3

and may also involve cortical gray matter, the thalamus, or the basal ganglia. Usually when there is a history of MS, the plaques of demyelination are evident on gross examination; however, there are exceptions in which the identification of the lesions requires microscopic examination.3

FIG. 19.1. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain of a patient with multiple sclerosis. Two prominent foci of demyelination are present in the periventricular white matter (arrows). |

Microscopically, the lesions of multiple sclerosis can be examined with hematoxylin and eosin stains, but are best seen on stains for myelin such as Luxol fast blue (LFB) (Fig. 19.3). The hallmarks of MS lesions are inflammation, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, demyelination, loss of oligodendrocytes, and degeneration of axons.4, 5, 6, 7 The plaque of demyelination may be active or inactive.8 The latter appears pale, with fewer oligodendrocytes than the adjacent normal white matter, and shows intense proliferation of reactive astrocytes. In the active lesions, there are venules displaying perivascular cuffing with mononuclear cells and occasionally edema and myelin-laden macrophages.9, 10, 11 With the aid of double stains for axons and myelin (i.e., Bodian silver for axons and LFB for myelin), it is possible to observe that in the demyelinating lesions, axons are spared, yet are without myelin. This selective vulnerability of oligodendrocytes and myelin is relative, however, because axons are also eventually damaged as bystanders by the recurrent bouts of inflammation and demyelination. Indeed, loss of nerve fibers and neurons can contribute significantly to the cerebral atrophy and neurologic dysfunction in multiple sclerosis.12 Importantly, lesions of MS are not confined to the white matter and can also involve the cerebral cortex.13, 14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree