DISH and Related Disorders

Theodore A. Belanger

Dale E. Rowe

BACKGROUND

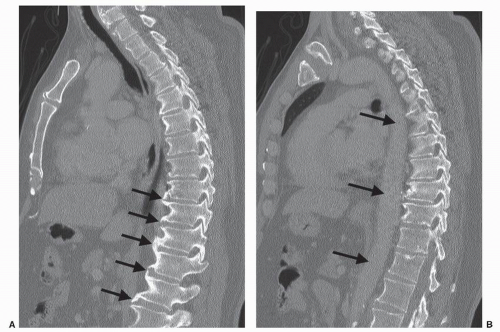

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), also known as Forestier’s disease, is a bone-forming diathesis characterized by stiffness, osteophytosis, and several specific radiographic findings (1, 2 and 3). The differential diagnosis includes several other disorders characterized by neck stiffness and spondylophyte formation (Table 64.1). The presence of “flowing” ossification along the ventrolateral margins of at least four contiguous vertebrae in the absence of spondyloarthropathy or degenerative spondylosis substantiates the diagnosis of DISH radiographically. These findings are nearly universally noted on the right side of the thoracic spine, with the left side usually spared (Fig. 64.1). This is felt to be secondary to a protective effect of the pulsatile aorta, as it occurs on the opposite side in those with situs inversus. When found in the cervical or lumbar region, the process is usually symmetric. Though association with other disorders such as increased body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, glucose intolerance, hyperuricemia, and dyslipidemia has been proposed, no convincing evidence linking DISH to other systemic disorders exists, and the etiology remains unclear (1,4,5).

DISH is relatively common in the general population. The prevalence of radiographic and pathologic findings increases with advancing age. An autopsy series by Boachie-Adjei and Bullough reported a 28% prevalence of findings consistent with DISH in subjects with an average age of 65 (6). Others have estimated the prevalence to be between 15% and 25% for those over 50 and 25% to 30% for those over 80 years of age, with a slight male predominance (7, 8 and 9). There does not seem to be a significant difference in prevalence of the disease among racial subsets.

The clinical presentation of DISH is typically in a middle-aged or older patient with chronic mild pain in the mid- and/or lower back, spinal stiffness (either the neck or lower back), and the characteristic radiographic findings. These radiographic findings are often noted incidentally when no significant complaints related to the spine exist. It is quite common to note radiographic changes in the thoracic spine on a chest radiograph as an incidental experience. Rarely, a patient may experience tendinitis where extraspinal enthesopathy exists, most commonly in the Achilles tendon.

The radiographic hallmark of DISH is the presence of nonmarginal syndesmophytes that appear as “flowing” ossification along the ventrolateral margins of the spine spanning the disk spaces. Since they are ventrolateral, they are usually visible on both ventrodorsal and lateral radiographic views. Strictly speaking, the presence of degenerative changes such as severe disk narrowing, marginal sclerosis along the disk spaces, or vacuum disk phenomenon should preclude the diagnosis of DISH. Similarly, findings of ankylosing spondylitis must also be excluded, such as facet ankylosis, sacroiliac erosions or sclerosis, or marginal syndesmophytes. The syndesmophytes of DISH tend to project away from the vertebral end plate horizontally with a flowing appearance that goes outside the margin of the annulus (i.e., nonmarginal syndesmophytes), while the marginal syndesmophytes typical of ankylosing spondylitis project more vertically from the end plate and are typically more thin and frail in appearance, present along the margin of the annulus. Osteopenia, typical of ankylosing spondylitis, is not characteristic of DISH.

Involvement of the cervical spine is less frequently recognized than the thoracic or lumbar spine (7). Pain and stiffness of the neck may be prominent or absent and are rarely presenting complaints. Radiographic findings are more common in the caudal segments, becoming less common in the more cephalad levels (Fig. 64.2). Ankylosis can occur through the uncovertebral joints, distinguishing DISH further from ankylosing spondylitis where ankylosis typically occurs through the facetjoints and ultimately across the disks. Mild cervical kyphosis, stenosis, radiculopathy, and/or myelopathy can occur in the setting of cervical DISH. Dysphagia, hoarseness, sleep apnea, and difficulty with endotracheal intubation have all been reported secondary to protrusion of large syndesmophytes into surrounding soft tissue structures (10, 11 and 12).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR SURGICAL TREATMENT

Surgery is seldom necessary for DISH in the absence of an associated disorder such as stenosis, trauma, or severe dysphagia. Symptoms of DISH are generally mild, and most of

the sequelae are not strong indications for surgery. When surgery is indicated, it is usually for the typical degenerative or traumatic conditions that spine surgeons treat in the non-DISH population. Occasionally, however, the surgical plan may require modification.

the sequelae are not strong indications for surgery. When surgery is indicated, it is usually for the typical degenerative or traumatic conditions that spine surgeons treat in the non-DISH population. Occasionally, however, the surgical plan may require modification.

TABLE 64.1 Differential Diagnosis for Cervical Stiffness and Spondylophytosis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Like other ankylosing conditions of the spine, patients with cervical DISH can sustain highly unstable injuries to the cervicothoracic junction from low-energy trauma. They are also more prone to sustaining displaced odontoid fractures due to the stress concentration that occurs in the upper neck when their cervical spine is ankylosed. Given the additional stiffness adjacent to these fractures, nonoperative treatment may be more likely to fail, and surgical treatment may need to be more aggressive (13,14).

Of rare but major concern in treating patients with ankylosing conditions who sustain fractures of the cervical spine is the heightened risk of epidural hematoma. This is classically an issue for patients with ankylosing spondylitis who sustain fractures in the setting of a rigid spine with kyphotic deformity and osteoporotic bone (15). The spine surgeon must be aware that these conditions can occasionally be simulated in patients with extensive DISH or other ankylosing disorders, and when it occurs, surgery may be indicated to preserve neurologic function.

Another rare but disabling situation that can arise in the setting of severe cervical spine ankylosis is the development of a “pseudotumor” in the upper cervical region (16, 17, 18 and 19). This presents as upper-level myelopathy or brainstem compression from development of a mass at the C1/C2 level, presumably from hypertrophic pannus

formation at the isolated motion segment above a rigid, ankylosed subaxial spine. When identified, patients often have severe neurologic complaints and findings, necessitating surgical treatment.

formation at the isolated motion segment above a rigid, ankylosed subaxial spine. When identified, patients often have severe neurologic complaints and findings, necessitating surgical treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree