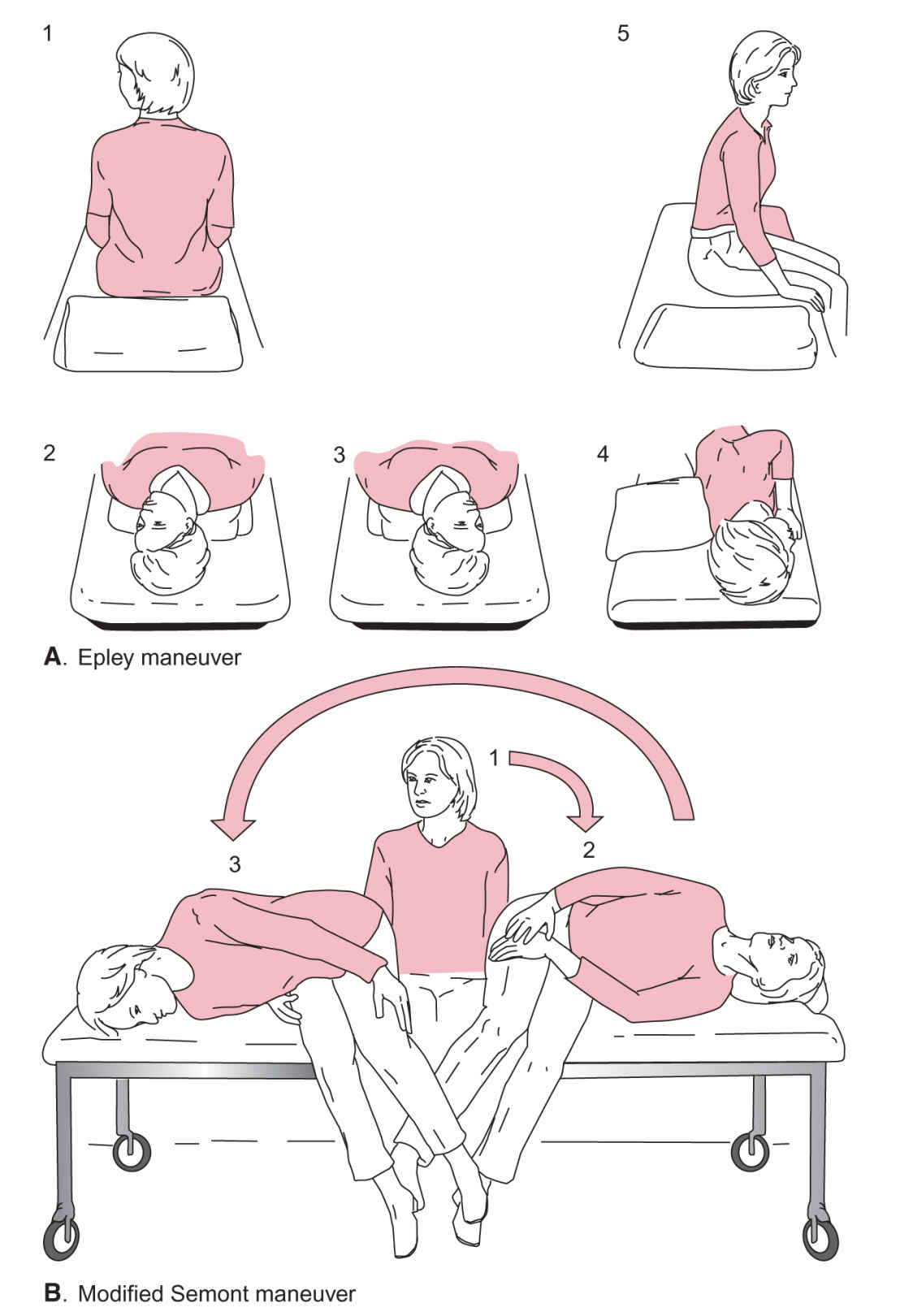

(Video 61.1) is a common technique used for canalith repositioning. It is most effectively used when the affected semicircular canal has been identified and can therefore be targeted for repositioning.

(1) Technique (Fig. 61.1).

(a) With the patient sitting upright, the head is turned 45 degrees to the offending side.

(b) From this upright position with the head turned, the patient is reclined supine with slight neck extension; this position is held for at least 15 to 20 seconds while observing for nystagmus and/or inquiring about patient subjective dizziness.

FIGURE 61.1 Self-treatment of BPPV. A: Epley maneuver. B: Modified Semont maneuver. (From Radtke A, von Brevern M, Tiel-Wilck K, et al. Self-treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: semont maneuver vs Epley procedure. Neurology. 2004;63:150–152, with permission.).

(c) After nystagmus abates, the head is then slowly rotated away from the offending side, through midline, 90 degrees to the opposite side pausing again to monitor for generated nystagmus and to allow abatement.

(d) Keeping the head and neck in a fixed position relative to the body, the individual rolls onto their side, effectively rotating the head another 90 degrees away from the affected ear, completing a 180-degree rotation and pausing to allow nystagmus to abate.

(e) After resolution of nystagmus and vertigo, the patient is returned to a seated position.

b. Liberatory or Semont maneuver.

(1) Technique (described for left-sided BPPV):

(a) The patient sits upright on the edge of the bed with the head turned 45 degrees to the right.

(b) The patient drops his/her head quickly to touch the left postauricular region to the bed while lying on the left trunk side and maintains this position for at least 30 seconds.

(c) Keeping the head and neck in a fixed position relative to the body, the patient then swiftly rolls onto the right trunk side to touch the right side of the forehead down and maintains this position for at least 30 seconds.

(d) The patient sits up again.

These maneuvers should be performed multiple times per day as tolerated until symptoms abate.

c. Surgery. Very rarely, repositioning techniques are ineffective, and in severe cases of refractory BPPV, surgery may be offered. Surgical options include semicircular canal plugging and vestibular neurectomy.

3. Results. When applied to patients with BPPV, canalith repositioning is successful in relieving symptoms in up to 90% of patients. The techniques can be performed and taught by a wide range of clinicians. In those patients with recurrent symptoms, teaching the patient repositioning techniques will allow for self-treatment.

4. Special circumstances. When BPPV is bilateral, treatment begins with the side that has a more robust nystagmus on Dix–Hallpike testing. Patients with severe disease may need pretreatment with 5 to 10 mg of diazepam 30 minutes before respositioning.

B. Vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis.

1. Clinical features. Vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis are often discussed together because of their similar presenting feature of vertigo lasting for days to weeks, although labyrinthitis is associated with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), whereas vestibular neuritis is not. These conditions are typically self-limited and are generally attributed to a viral infection. During the acute phase of vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis (acute vestibular syndrome), many patients present to the emergency department or urgent care concerned by the duration and intensity of their symptoms. Thorough assessment and, sometimes, imaging are necessary to rule out more serious cause of vertigo including vertebrobasilar stroke. After the acute phase, vestibular equilibrium gradually returns over the course of several weeks in most patients.

2. Treatment. Using a combination of vestibular suppression, anti-inflammatory agents, antiemetics and vestibular rehabilitation, treatment aims to reduce the severity and duration of acute symptomatology while allowing for vestibular recovery.

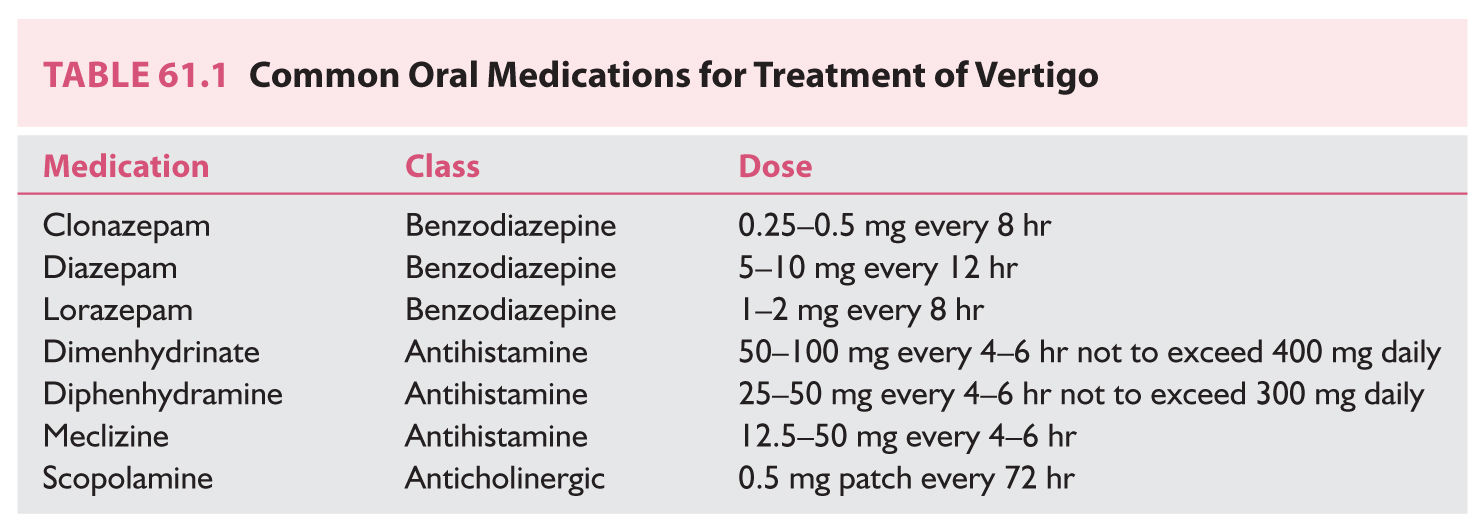

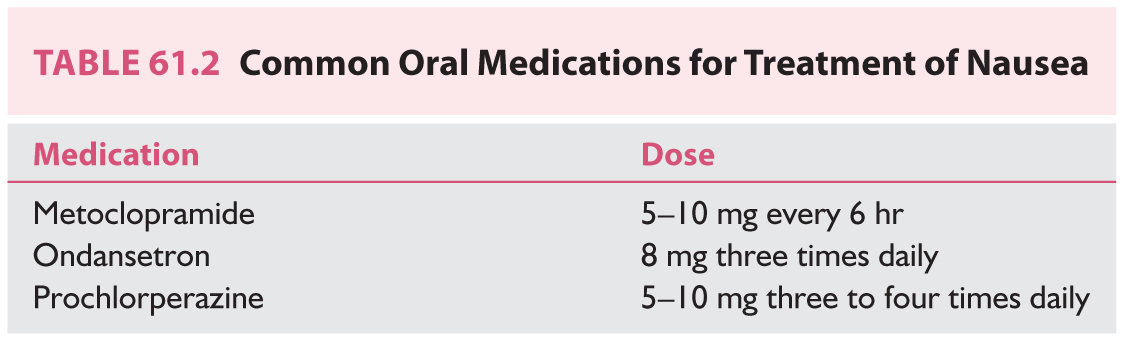

a. Vestibular suppression. Vestibular suppressants are generally grouped into three categories: benzodiazepines, antihistamines, and anticholinergics (Table 61.1). Benzodiazepines work through γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) potentiation and subsequent inhibition of vestibular stimulation. Anticholinergics and antihistamines work to suppress vestibular input. These medications are generally well tolerated in low doses. However, it is important to realize that a high level of vestibular suppression may reduce central compensation and ultimately hinder recovery—“the brain can’t fix what it can’t see.” Thus, it is wise to use vestibular suppressants in a limited fashion. Antiemetics are a fourth category of pharmacotherapy often used concurrently with vestibulosuppressants to target frequently associated nausea.

(1) Antihistamines. Antihistamines, notably those of the histamine-1 antagonist group, are commonly used in the management of peripheral vertigo. They are believed to exert a vestibulosuppressant effect via a central anticholinergic mechanism. Meclizine is most commonly used, starting at small doses (12.5 to 25 mg two to three times daily) and titrating to effect. Its effect is limited, with adequate suppression typically lasting only 1 to 2 months. Promethazine is another antihistamine that also has antiemetic properties.

(2) Anticholinergics. Scopolamine is an anticholinergic medication commonly used in the prevention of motion sickness. It is not as valuable in the management of acquired vestibulopathy, but may be effective in the prophylaxis of motion sickness.

(3) Benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines are a class of psychoactive drugs that work through central inhibitory GABA potentiation resulting in anxiolysis, sedation, and, in some cases, amnestic, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxation effects. Lorazepam and diazepam are frequently used for their ability to prevent and mitigate attacks of dizziness and vertigo from a variety of etiologies. Diazepam at a low dose (5 to 10 mg) acts as a vestibulosuppressant and can be used for acute or chronic otologic dizziness. Care must be taken when utilizing benzodiazepines because of their increased potential for dependence and subsequent withdrawal symptoms on cessation of therapy.

(4) Antiemetics (Table 61.2). Antiemetics are used to relieve nausea and vomiting associated with vertigo. Prochlorperazine is a phenothiazine that exerts a strong antiemetic effect but also carries the risk of extrapyramidal side effects. Metoclopramide is a dopamine receptor antagonist and serotonin receptor antagonist/agonist with antiemetic and prokinetic properties. Ondansetron provides antiemesis via serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonism.

b. Corticosteroids/antivirals/antibiotics. High-dose oral corticosteroids or intratympanic corticosteroids administered by an otolaryngologist may be effective in treating labyrinthitis-associated hearing loss. Prompt audiological evaluation and ENT referral are paramount because early initiation of corticosteroid therapy may improve hearing outcomes. Although most cases of labyrinthitis are believed to arise from viral infection, the addition of antiviral therapy to corticosteroids has not been shown to offer additional benefit. Antibiotics are of value in cases of bacterial or suppurative labyrinthitis; however, the decision to use antibiotics should be dictated by objective signs of infection.

c. Vestibular rehabilitation. Vestibular rehabilitation refers to physical therapy aimed at enhancing recovery from peripheral vestibulopathy. The exercises range from simple head-turning to increasingly more complex postural and ambulation challenges with and without head movement. Simple walking is a form of vestibular rehabilitation that can be recommended to patients with limited disequilibrium. The earlier vestibular rehabilitation takes place, the better the outcome, and patients should be titrated off vestibular suppressants to optimize vestibular challenge and recovery.

3. Results. Although there is some support for steroid use and vestibular rehabilitation enhancing vestibular recovery, randomized control trials are lacking. Fortunately, over 90% of patients with vestibular neuronitis or labyrinthitis will return to their presymptomatic baseline.

C. Ménière’s disease.

1. Clinical features. Ménière’s disease is characterized by the constellation of fluctuating SNHL, tinnitus, and vertigo. It is often associated with “aural fullness.” Episodes are recurrent and typically last 20 minutes or longer. Over time, the involved peripheral vestibular system experiences a reduction in responsiveness or “burns out.” It is a disease primarily of Caucasians, with a slight female bias and onset between 40 and 60 years of age. The histopathologic correlate is endolymphatic hydrops, the result of an overaccumulation of endolymph. One proposed pathophysiologic mechanism involves membranous labyrinth microruptures, allowing potassium-rich endolymph to mix with potassium-poor perilymph, thus disrupting biochemical gradients and neuronal conductivity.

2. Treatments. Treatment of Méniere’s disease is focused on vertiginous symptom control, as tinnitus and hearing loss are less amenable to intervention. Medical therapy is used at the outset of treatment, with more invasive options reserved for symptoms refractory to conservative management.

a. Nonablative.

(1) Acute. As in labyrinthitis, antihistamines, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, and antiemetics may be used to mitigate acute attacks of vertigo and nausea.

(2) Chronic. Salt-restricted diet and diuretics are the mainstays of medical treatment. Their efficacy is believed to result from a reduction in endolymph. A combination of hydrochlorothiazide and triamterene is a commonly used regimen and can be titrated to effect. Also limiting alcohol, caffeine, and stress may be beneficial. Those patients with poor symptom control despite these measures may then be offered nonablative options such as intratympanic steroid injection or endolymphatic sac surgery (ESS). ESS is a hearing-preserving, nonvestibular-ablative endolymphatic sac decompressive procedure. The mechanisms by which it reduces vertigo are controversial.

b. Ablative. For patients in whom conservative measures have failed, vestibular ablative options may be offered. Intratympanic gentamicin injection offers somewhat selective vestibular toxicity through a less invasive approach, but carries a significant risk of SNHL. Vestibular nerve section offers a high rate of vertigo control with minimal risk to hearing. Labyrinthectomy is a complete vestibular-ablative procedure well suited to patients with nonserviceable hearing.

3. Results. Diuretics have been shown to control vertigo and stabilize hearing in 50% to 70% of patients. In addition, the natural history of Meniere’s disease allows for spontaneous remission of episodic vertigo in 60% to 80% of patients. For those few with refractory vertigo, intratympanic steroid and endolymphatic sac decompression are effective at controlling vertigo in approximately 80% of patients, while ablative procedures such as intratympanic gentamicin, vestibular neuronectomy, and labyrinthectomy can control vestibular symptoms in greater than 90% of patients.

D. Perilymphatic fistula.

1. Clinical features. Perilymphatic fistula is a controversial clinical entity. Theoretically it is characterized by the abnormal communication of perilymph between the labyrinth and the middle ear via the oval window, round window, or an aberrant pathway. It may result from barotrauma, penetrating middle-ear trauma, or stapedectomy or may occur spontaneously. The controversy in its diagnosis centers on the difficulty in identifying a microfistula intraoperatively and the lack of clear clinical criteria. It is described most often as vertigo with extreme pressure sensitivity that may be exacerbated by Valsalva maneuver and pneumatic otoscopy. It may also be associated with sudden or gradual hearing loss, thus mimicking Ménière’s disease.

2. Treatments. Small fistulas may heal spontaneously with a short course of bed rest. In situations with stable hearing or when the clinical diagnosis is questioned, a trial of vestibular rehabilitation may be attempted. When there is a clear temporal relationship between a predisposing insult (e.g., scuba diving, ear surgery, or penetrating middle ear trauma), surgery in the form of an exploratory tympanotomy may be undertaken to localize and patch the fistula with autogenous connective tissue. Postoperatively, a course of bed rest is undertaken to allow healing of the graft and efforts are made to minimize Valsalva coughing and straining.

3. Results. Bed rest is successful in many patients, and in cases where the fistula is evident, surgery can be very effective. Consideration of an alternate diagnosis such as superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome may be necessary in patients who undergo negative exploration.

E. Superior canal dehiscence syndrome.

1. Clinical features. Superior canal dehiscence syndrome (SCDS) is a sound- and pressure-induced vertigo caused by bony dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. The characteristic torsional vertical nystagmus occurs in the plane of the affected canal with administration of sound and pressure changes. Patient complaints are variable and include autophony, sound-induced (Tullio’s phenomenon) or pressure-induced vertigo, conductive hearing loss, and/or pulsatile tinnitus. Clinically, SCDS symptomatology overlaps with perilymphatic fistula and acquired horizontal canal dehiscence from cholesteatoma or chronic otitis media. However, history and physical examination direct clinical suspicion, and high-resolution computed tomography demonstrating superior canal dehiscence is diagnostic.

2. Treatments. Surgical plugging of the affected superior canal can be beneficial in patients with debilitating symptoms because of this disorder.

3. Results. Success rates of surgical plugging of superior canal dehiscence are reported to range from 50% to 90%.

F. Ototoxicity.

1. Clinical features. Ototoxicity may be associated with a number of medications and manifests as hearing loss, tinnitus and/or dizziness, and vertigo. Clinically significant ototoxicity is commonly associated with aminoglycosides and other antibiotics, platinum-based antineoplastic agents, salicylates, quinine, and loop diuretics. The aminoglycoside gentamicin is notably vestibulotoxic, and this property is selectively utilized when intratympanic injections are administered for vestibular ablation as previously mentioned. Cessation of ototoxic agent exposure will halt the continued insult, but recovery is variable and may be incomplete.

2. Treatments. Paramount to treatment is the avoidance of ototoxic medications whenever possible. Active treatment options are limited to vestibular rehabilitation and symptomatic supportive measures while central compensation and adaptation of the vestibulospinal and vestibulocervical reflexes occur.

3. Results. Although these compensatory mechanisms are of value, they are not typically sufficient in restoring complete function. Certainly prevention, if possible, is more effective than treatment in this condition.

G. Tumors involving the vestibulocochlear nerve.

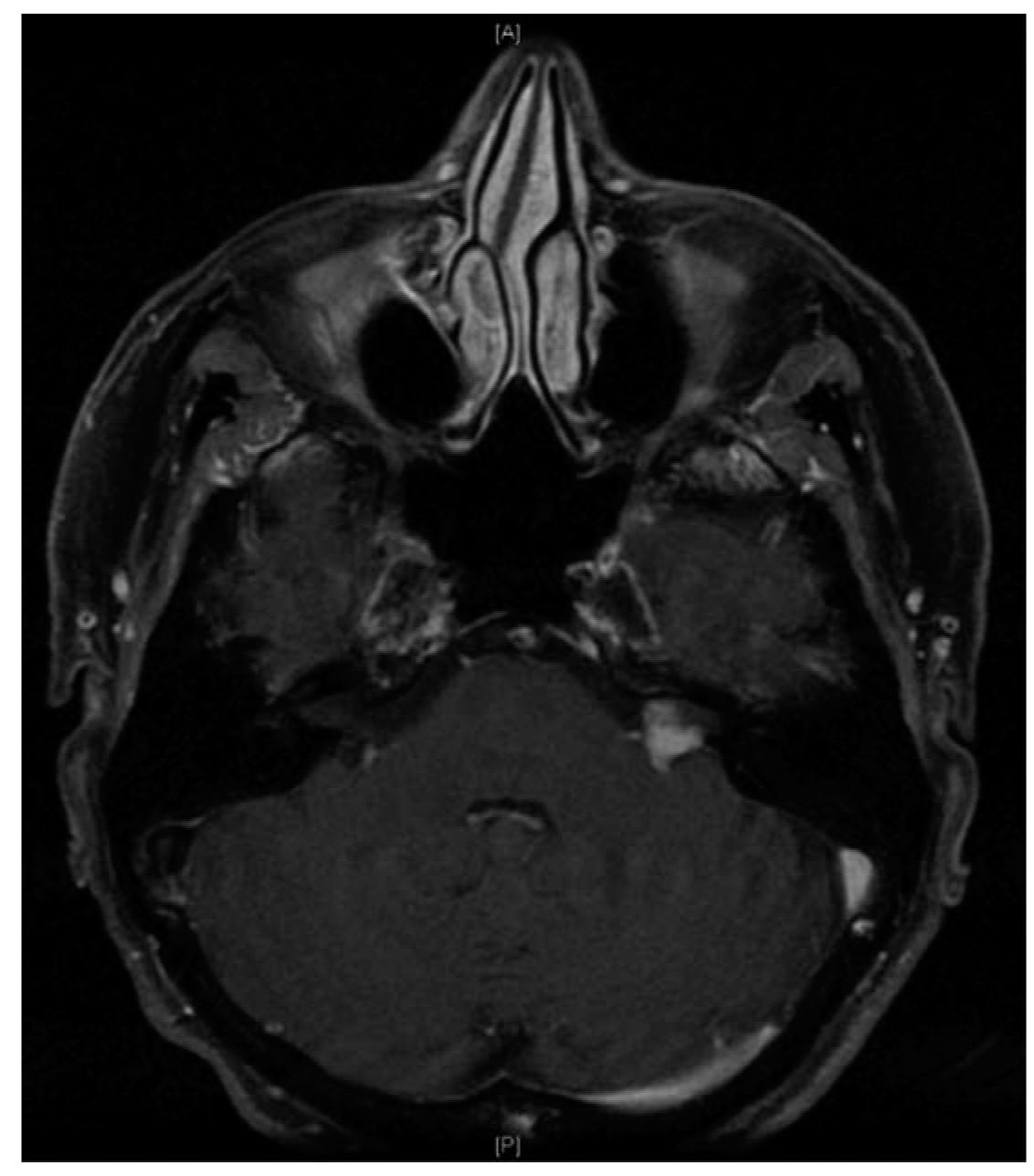

1. Clinical features. Vestibular schwannoma is the most common lesion of the cerebellopontine angle (Fig. 61.2). These benign, slow-growing tumors can occupy the vestibular division of the eighth cranial nerve from the internal auditory canal to the cerebellopontine cistern. As the tumor enlarges, it can cause vestibulocochlear nerve dysfunction both from local compression as well as disruption of blood supply. Tumor progression is typically slow, allowing for contralateral vestibular and central compensation to mask vestibular loss. More commonly, unilateral hearing loss and tinnitus prompt patients to seek care. Advanced tumors may show signs of vestibulopathy and result in life-threatening hydrocephalus and brainstem compression.

2. Treatments. The slow-growing nature of vestibular schwannoma combined with varied clinical presentation requires that treatment options be tailored to each patient. Large tumors require surgical resection. Smaller tumors may be observed, because a certain percentage of tumors are quiescent. Growing tumors less than 2.5 cm may be considered for radiation treatment, which functions to arrest tumor growth in a large portion of patients. Microsurgical resection offers a chance for complete tumor resection with a low rate of recurrence. Patient age, comorbidity, hearing status, and documentation of tumor growth must be considered in treatment planning.

FIGURE 61.2 Left cerebellopontine angle vestibular schwannoma on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted axial MRI.

3. Results. Success rates in the treatment of vestibular schwannoma must be weighed against the quiescent natural history of some tumors. Radiation therapy tumor control rates are reported to be greater than 95% in some series, although it is unknown what percentage of these tumors were growing. Outcomes for microsurgical control of vestibular schwannomas are comparable to radiotherapy. Hearing preservation is not always possible with surgery and is dependent on tumor size and location. However, hearing tends to decline in all vestibular schwannomas and it tends to decline in observed and radiated tumors at a similar rate, with hearing declining more rapidly in faster-growing tumors.

CENTRAL NEUROLOGIC CAUSES OF VERTIGO

A. Ischemia or infarction.

1. Clinical features. Disruption of vertebrobasilar circulation to the brainstem, cerebellum, and peripheral vestibular system can cause dizziness and vertigo. The hallmark of this ischemia is the association of vertigo with other focal neurologic findings, particularly in a predictable anatomic distribution. Weakness, facial paresthesia, dysarthria, ataxia, diplopia, and visual disturbances are examples of symptoms that may also be present with transient ischemia or infarction of the brainstem. Because transient ischemia may be responsible for episodic vertigo, it is important to recognize it as such to prevent potential stroke.

2. Treatments. General supportive measures and the use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications remain the cornerstones of medical therapy for the management of acute ischemic stroke. More importantly for the clinician evaluating episodic dizziness in the outpatient center is the recognition of signs of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs). Preceding TIAs are a risk factor for atherothrombotic brain infarction and should prompt evaluation of other vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, dyslipidemia, and smoking. Additionally, cardiac evaluation may be warranted in search of possible cardioembolic sources depending on presenting signs. Further discussion on the treatment and prevention of ischemic cerebrovascular disease is discussed elsewhere in Chapter 40.

3. Results. Appropriate lifestyle modifications and the addition of antithrombotic (antiplatelets or oral anticoagulants when indicated) therapy are effective in reducing the incidence of stroke and permanent deficit after stroke in at-risk individuals. No therapy is 100% effective.

B. Basilar migraine and migrainous vertigo.

1. Clinical features. Classically described as a condition of adolescent females, basilar migraine (see ICHD-II) can affect males and females of any age though it does have a female preponderance. It is characterized by an aura causing hemianopic visual changes, vertigo, ataxia, numbness, or dysarthria followed by a throbbing occipital headache often associated with nausea. Symptoms are self-limited, with the aura lasting from a few minutes to an hour and a headache of variable duration. Basilar migraine is considered a distinct clinical entity from migrainous vertigo, which is characterized by episodic vertigo, but without related neurologic symptoms and in some cases, even without headache. Because it is more difficult to diagnose without the associated symptoms, some question migrainous vertigo as a clinical entity. Diagnosis of migrainous vertigo relies on indirect evidence in the form of relationship of symptoms to migrainous triggers and response to antimigraine medications. In both cases, and particularly with vertibrobasilar migraine, there is overlap between migrainous symptoms and those of more serious cerebrovascular derangement, and a thorough evaluation should rule out other causes of vertigo before the diagnosis of migraine is applied.

2. Treatments. Multiple treatment regimens exist for migraine. Abortive medical therapy is directed at resolving the symptoms shortly after onset. Medications such as ergotamine and the triptans fall into this category. Patients whose symptoms are more frequent may be candidates for preventive medical therapy in the form of beta-blocking agents, tricyclic antidepressants, antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), and calcium-channel blockers. The treatment of migraine is discussed elsewhere in this text.

3. Results. With proper selection of medical therapy, the majority of migraine patients can achieve the goal of symptom prevention.

C. Multiple sclerosis (MS).

1. Clinical features. MS is often diagnosed in young adults. Vertigo can be an associated symptom of CNS dysfunction and may be followed some time later with isolated weakness or visual disturbance. Clinical diagnosis is confirmed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

2. Treatments. There are a number of immunomodulating agents used in the treatment of MS. These and other treatments are discussed in more detail elsewhere in Chapter 40.

3. Results. MS is a highly variable disease, and its effects on patients are myriad. Treatments are also varied with inconsistent results. The goal of appropriate therapy is to mitigate the severity of attacks while reducing their frequency.

D. Chiari malformations.

1. Clinical features. Symptoms suggestive of Chiari include headache, vertigo, ataxia, tinnitus, hearing loss, weakness, and numbness. Chiari malformations are often associated with downbeat nystagmus in the primary position.

2. Treatments. Conservative measures consisting of symptomatic control may be appropriate in certain patients. Those with progressive disease may require surgical decompression of the posterior fossa.

3. Results. Surgical decompression often relieves or at least halts the progression of brainstem compressive symptoms.

A. Postural hypotension.

1. Clinical features. Postural hypotension is a classic finding in elderly patients and may result from any number of causes. Symptomatically it is described as lightheaded or presyncopal feeling when standing from sitting or lying. It can result from diminished cardiac output, antihypertensive medication with associated vasodilation or beta-blockade, dehydration, or autonomic insufficiency from underlying diabetic neuropathy, for example.

2. Treatments. Most important in the treatment of postural hypotension is to recognize it as such. With this in mind, a systematic hemodynamic review must be undertaken. Modification of a current medication regimen is straightforward. Exercise and improved hydration can improve underlying cardiac decompensation, and elastic stockings may be of benefit in optimizing cardiac return.

3. Results. Proper identification of hemodynamic insufficiency allows treatment modifications where able and is often successful at reducing the severity and frequency of postural hypotension.

B. Arrhythmia.

1. Clinical features. Symptoms of cardiac arrhythmia frequently include palpitations with or without chest pain. They may be associated with presyncope or even loss of consciousness but are not typically associated with true vertigo. Diagnostic workup includes cardiac monitoring, particularly during an episode, to secure the diagnosis.

2. Treatments. Cardiology referral is undertaken for evaluation and management of cardiac arrhythmia. Antiarrhythmic medications, pacemakers, and radiofrequency ablation of aberrant pathways of conduction may all be considered in treatment.

3. Results. Appropriate treatment can be very effective in managing most cardiac arrhythmias.

C. Hypoglycemia.

1. Clinical features. Metabolic derangements such as insulin-dependent diabetic hypoglycemia may be responsible for dysequilibrium but rarely true vertigo. Episodes of hypoglycemia and dysequilibrium may present acutely in patients who have used insulin for years.

2. Treatments. Treatment of hypoglycemia is acutely directed at increasing the serum blood glucose level and may require tailoring the diabetic regimen to prevent future episodes.

3. Results. Targeted treatment along with patient education is usually successful at resolving or decreasing the frequency of symptoms.

D. Medication-associated.

1. Clinical features. Medications that mediate CNS effects, such as AEDs, benzodiazepines, and psychogenics, may cause primary effects and side effects that create a sensation of dysequilibrium. This dysequilibrium is distinct from postural hypotension that may arise from antihypertensive medications as described above.

2. Treatments. Treatment is aimed at identifying, limiting, and/or removing the offending medication. Ideally, an alternative medication is found that offers a similar therapeutic profile.

3. Results. Removing the offending medication will remove the associated symptoms, but as with most medications, treatment effect must be weighed against side-effect profile.

E. Infection.

1. Clinical features. Infectious labyrinthitis occurring because of a number of viral, bacterial, and fungal agents may cause vertigo. Patient exposures, vaccination history, and associated signs and symptoms help to narrow the differential diagnosis.

2. Treatments. Identification of the causative infectious agent allows effective treatment with antibiotics, antivirals, or other supportive measures. Administration of mumps, rubella, rubeola, and varicella-zoster vaccines is the best method to prevent viral inner ear infections. Hearing aid and cochlear implantation are audiologic rehabilitation options as well.

3. Results. Results of treatment largely depend on the infectious etiology.

UNLOCALIZED VERTIGO

A. Psychogenic. Anxiety, depression, and personality disorder are common codiagnoses in patients complaining of dizziness. It is a bidirectional relationship in that severe organic vertigo can cause symptoms of depression and anxiety given the potential unpredictability of attacks. In addition, patients with primary psychiatric diagnoses may also identify dizziness as a complaint, described as an out-of-body experience, a sense of floating, or a racing sensation. It is important not to label a patient with a psychiatric diagnosis as having psychogenic dizziness until organic causes have been ruled out. Treatment should be directed at managing both organic and psychogenic factors simultaneously. SSRI medications and other antidepressants may be valuable in that role.

B. Malingering. Unfortunately, there are patients who misrepresent their symptoms for secondary gain. Objective testing, such as posturography, can be used to identify patients who may be falsely complaining of symptoms of dizziness.

C. Postconcussive. Concussions may be the result of mild to moderate traumatic brain injury (TBI) resulting in transient neurologic deficit with normal computed tomography imaging of the brain. Nausea, vomiting, headache, and dizziness may present acutely. Focal neurologic deficits typically resolve over weeks to months following mild to moderate TBI, but cognitive, psychological, and emotional dysfunction may persist in more severe injuries. Supportive measures and vestibular rehabilitation are utilized to speed vestibular recovery.

D. Multifactorial. Because balance is a multifactorial process maintained through visual, proprioceptive, and vestibular input, decline in one component may be masked through central compensation mechanisms. In some patients, however, particularly the elderly multiply comorbid patient, a decline in balance input may not be met with adequate central compensation and equilibrium will be difficult to reestablish. Peripheral neuropathy, poor vision, and multiple vestibulosuppressant medications are examples of factors contributing to dysequilibrium that should be addressed. Continued walking, with assistance if necessary, is often recommended in an effort to prevent further decompensation.

E. Unknown. Although thorough history, physical examination, and judicious ancillary testing are effective in identifying the cause of dizziness in most patients, there remain those few whose symptoms arise from an unidentifiable source. This can be frustrating for both clinician and patient, and requires the clinician to counsel the patient regarding reasonable expectations in achieving a mutually acceptable outcome.

Key Points

• Vertigo is a symptom for which numerous differential diagnoses must be examined. Peripheral vestibular, otologic, and central neurologic disorders as well as medical causes should be considered.

• True vertigo, particularly rotatory vertigo, is often because of a peripheral vestibular (inner ear) disorder.

• BPPV is the most common cause of peripheral vertigo. Repositioning exercises effectively treat the disorder by moving debris from the affected semicircular canal.

• Labyrinthitis and vestibular neuritis cause vertigo that lasts days to weeks. Both disorders are generally attributed to a viral infection.

• Ménière’s disease is characterized by the constellation of fluctuating SNHL, tinnitus, and vertigo.

• When prescribing benzodiazepines, antihistamines, and anticholinergics, it is important to remember that a high level of vestibular suppression may reduce central compensation and ultimately hinder recovery.

• Peripheral neuropathy, poor vision, and multiple vestibulosuppressant medications should not be overlooked as factors contributing to disequilibrium.

• Diagnosis of migrainous vertigo is often made when there is a relationship between symptoms and exposure to migraine triggers. Many patients improve with diet changes and/or migraine medications.

• Vertigo associated with focal neurologic findings such as weakness, facial paresthesia, dysarthria, ataxia, diplopia, and/or visual disturbances suggests ischemia and potential for stroke.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree