4 Doctor–patient communication

Introduction

This chapter considers the general issue of doctor–patient communication for medicine in general and specifically for psychiatry. Various theoretical aspects of the workings of the mind are described that provide a basis for understanding patient and doctor functioning (‘dynamic psychopathology’). Chapter 5 describes the content of the psychiatric interview and assessment.

First contact

A distinction has been made between disease, the pathological abnormality occurring as a result of some specific noxious insult, and illness, the subjective interpretation of problems that are perceived as related to health. These are related to each other but can occur independently. Illness without disease can, for example, be malingering, hypochondriasis or somatization (the distinctions are covered in Chapter 11). In other ‘non-psychiatric’ disorders there may be a strong psychological contribution with varying levels of pathological or physiological change (e.g. tension headache, irritable bowel syndrome). A similar distinction has been made between:

Setting

The layout of all settings should try to ensure that patient and doctor are at a similar height, that there is no barrier to communication (e.g. a desk) and that eye contact is possible but not forced. Placing similar chairs at an angle of 90° to each other usually achieves this, possibly with a low table to one side. If the doctor requires a writing surface, the doctor sitting to one side of the desk (Figure 4.1) can achieve a similar effect. Lighting should be adequate but not too bright, and should not shine in the patient’s eyes.

Behaviour

Looking interested also facilitates disclosure. It is important for the doctor to examine personal attitudes at the outset of the interview, as a jaded or bored state of mind will be picked up by the patient and will interfere with the quantity and quality of the information derived by the doctor. (Non-verbal communication is continuous and on the edge of consciousness. Where there is an inconsistency between verbal and non-verbal communication the latter takes precedence.) Leaning forward, nodding and slightly inclining the head tend to encourage further disclosure. Looking at the patient also gives the impression of listening. In normal circumstances, while patients are talking, they will not maintain eye contact all the time but will keep checking that the listener is paying attention, and may fix their gaze at important junctures (Figure 4.2). If the doctor is looking at the notes while the patient is talking, the quality of the communication deteriorates significantly.

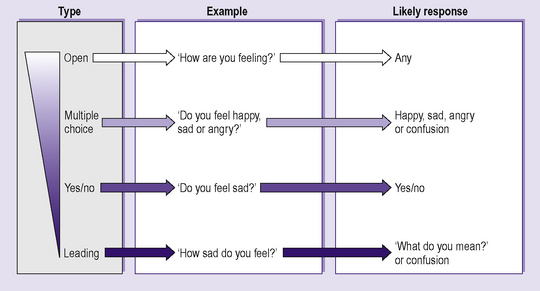

Questioning should progress from open (‘Can you tell me of your concerns?’ … ‘Tell me more about that’ …) to more specific closed questions (‘When did your father die?’). Different types of question will tend to produce different responses (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 • Type of question (in order of decreasing openness and increasing chance of limited response).

All the doctor’s senses will be necessary for an accurate and effective diagnosis and treatment:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree