14 Sleep disorders

Normal sleep

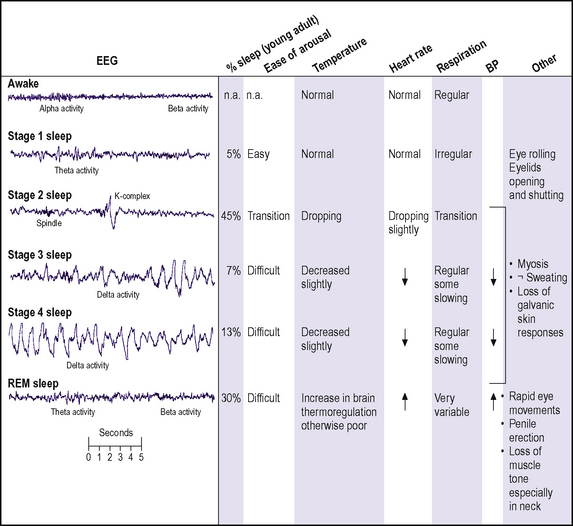

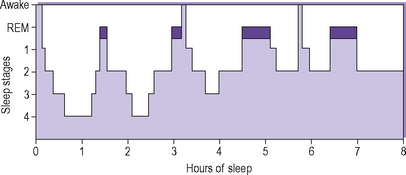

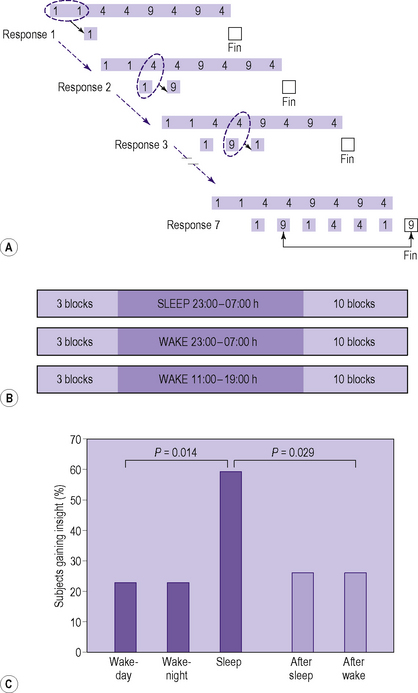

Sleep is usually described as a series of phases characterized by changes in physiological variables, most notably the electroencephalogram (EEG), as illustrated in Figure 14.1. There is usually a typical body posture (associated with good thermoregulation); physical inactivity; more stimulation required to arouse than during wakefulness; a specific site or nest for this behaviour; and regular daily occurrence. The progression between the phases can be shown by means of a ‘hypnogram’ (Figure 14.2). There are a number of theories regarding the function of sleep (listed in Table 14.1). Evidence is accumulating for each, suggesting that sleep serves a number of functions. Sleep has been found to facilitate mathematical insight, as shown in Figure 14.3.

Figure 14.2 • A hypnogram of sleep stage changes of the night in normal young adults.

(Reproduced with permission from Horne J 1985 Why we sleep. Oxford University Press, Oxford.)

| Conservation of energy – energy use decreases to between 5–% and 25% of waking level |

| Restorative – sleep allows the body to ‘mend itself’ after the ravages of the day. Anabolism/catabolism ratio increases. Increased growth hormone release |

| Consolidation of memory |

| Vestigial – sleep is the remnant of a mechanism useful at an earlier stage of evolution |

| Safety – superficially similar to death, sleep may discourage predators from attack, but those animals more at risk of attack sleep less |

| Social bonding – the clustering of humans at sleep time may be useful in keeping a social group together |

| To dream – the function of dreaming is not clear, but if artificially suppressed (e.g. with drugs) there is a significant increase on the cessation of suppression. This suggests that dreaming may serve an important function |

| Behavioural – sleep occurring because of the absence of stimulation and the lack of anything better to do |

| Humoral – due to accumulation of sleep-inducing substances in the brain during wakefulness |

Figure 14.3 • Facilitation of mathematical insight by sleep.

(Reproduced with permission from Wagner U et al 2004 Nature 427:352–355)

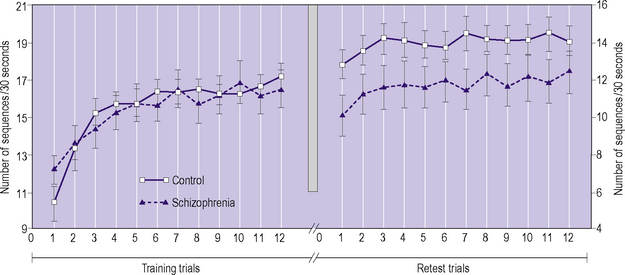

Normal sleep-dependent consolidation of memory is disrupted in schizophrenia. This is illustrated in Figure 14.4.

Figure 14.4 • Sleep-dependent consolidation of memory.

(Reproduced with permission from Manoach DS et al 2004 Biological Psychiatry 56:951–956.)

Length of time asleep

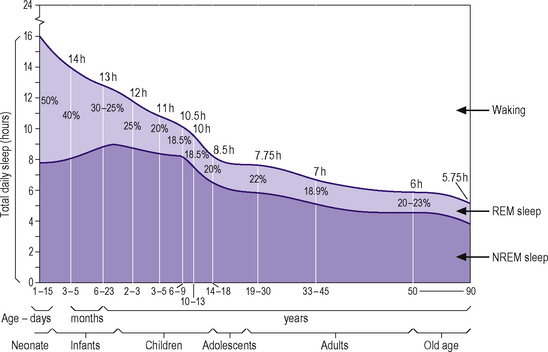

Humans spend, on average, 25% of their lives asleep. There is variation in sleep time, both in individuals during the course of development and the life cycle, and also between individuals (Figure 14.4). The individual differences within and between subjects are particularly noticeable in infancy. The mean daily sleep length in the first week of life is 16 hours (SD two hours). There is a gradual reduction in mean daily sleep length throughout infancy and middle childhood (Figure 14.5). Most infants wake at least once each night but, apart from babies who need feeding (more often those who are breastfed), they usually drop off to sleep again by themselves. Parents are not normally aware of this unless they themselves are having problems sleeping. Adults will also wake briefly during the night but often will not remember. Frequency of waking increases with age.

Figure 14.5 • Changes with age in total amounts of daily sleep and daily REM sleep.

(Reproduced and modified with permission from Roffwarg et al. 1966 Science 152: 604–619.)

Classification of sleep disorders

Sleep disorders may be divided into those primarily of emotional origin and those with an organic basis. The ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR categorizations of sleep disorders are shown in Tables 14.2 and 14.3 respectively. This chapter will cover predominantly those sleep disorders with a psychiatric basis. However, sleep disorders with organic causes are important differential diagnoses and interactions with psychological factors are usual. Also, sleep disorders are often a component or complication of other psychiatric disorders.

Table 14.2 ICD-10 classification: F51 Non-organic sleep disorders

| F51.0 Non-organic insomnia |

| F51.1 Non-organic hypersomnia |

| F51.2 Non-organic disorder of the sleep–wake schedule |

| F51.3 Sleepwalking |

| F51.4 Sleep terrors |

| F51.5 Nightmares |

Table 14.3 DSM-IV-TR Sleep disorders

| Primary sleep disorders |

| Dyssomnias |

307.45 Circadian rhythm sleep disorder (Specify type: Delayed sleep phase type/jet lag type/shift work type/unspecified type) |

| Parasomnias |

| Sleep disorders related to another mental disorder |

| Other sleep disorders |

NOS, not otherwise specified.

Insomnia

Aetiology

The causes of insomnia are summarized in Table 14.4.

| Environmental | Poor sleep hygiene |

| Change in time zone | |

| Change in sleeping habits | |

| Shiftwork | |

| Physiological | Natural short sleeper |

| Pregnancy | |

| Middle age | |

| Life stress | Bereavement |

| Exams | |

| House move, etc. | |

| Psychiatric | Acute anxiety |

| Depression | |

| Mania | |

| Organic brain syndrome | |

| Physical | Pain |

| Cardiorespiratory distress | |

| Arthritis | |

| Nocturia | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | |

| Thyrotoxicosis | |

| Pharmacological | Caffeine |

| Alcohol | |

| Stimulants | |

| Chronic hypnotic use | |

| Parasomnias | Sleep apnoea |

| Sleep myoclonus |

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree