Drug Treatment in the Elderly

Ilo E. Leppik

Angela K. Birnbaum

Introduction

The elderly are the most rapidly growing segment of the population, and demographic trends predict that their number is projected to increase in the United States from an estimated 40 million in 2010 to 71.5 million in 2030.1 Similar increases are expected throughout the world. The incidence (new cases) of epilepsy is higher in the elderly than in any other age group.33,34 Because of the rapid growth in their numbers and their propensity to develop epilepsy, elderly persons will represent an increasingly large group of patients needing expert care for this disorder. In the United States, approximately 181,000 persons developed epilepsy in 1995, and approximately 68,000 of these were >65 years of age.21 Similar high rates have been reported from the Netherlands and Finland.19,72 Problems faced by the elderly with epilepsy are different and more complex than those faced by younger adults with this disorder. These issues are medical (making the correct diagnosis, selecting the correct medication, working with comorbid illnesses), social, emotional, and economic.

One complicated area is selecting the appropriate antiepileptic drug (AED), which requires the consideration of a number of factors. These include changes in organ function, increased susceptibility to adverse effects, use of other medications known to interact with AEDs, and economic limitations. In addition, the elderly population is heterogeneous, and broad statements about the elderly may not be relevant to each individual patient. Treatment in the elderly carries more risks than in younger persons because they may experience more side effects, have a greater risk for drug interactions, and be less able to afford the costs of medications. In addition to their use in epilepsy, AEDs are prescribed for a variety of other disorders affecting the elderly, including pain and psychiatric disorders. As a cause of adverse reactions among the elderly, AEDs rank fifth among all drug categories.54 Unfortunately, very little research has been done in this vulnerable population, and only general recommendations can be made at this time.

The Elderly Are Not a Homogenous Population

Like the pediatric population, the elderly (65 years and older) are not a single cohort. Medical issues in persons up to age 18 years cannot be properly interpreted without using the subcategories of newborn, infant, child, and adolescent. Similarly, elderly persons should also be subdivided into appropriate cohorts. A widely used system divides the elderly into the “young-old” (those 65–74 years of age), the “middle-old” or “old” (those 75–84 years of age), and the “old-old” (those 85 years or older). However, because persons develop health issues at different times, further subdivisions have been proposed as shown in Table 1: (a) the elderly healthy (EH) who have epilepsy, (b) the elderly with multiple medical problems (EMMP), and (c) the frail elderly (FE), usually in nursing homes.48 Thus, one must tailor studies and interventions to nine categories of elderly with epilepsy. In addition, pediatricians must cope with the emotions of adult parents of children, who are often very caring and protective. Similarly, the physician caring for an elderly person with epilepsy must deal with the emotions of adult children of parents. Approaches needed by both groups of physicians have similarities.

In addition, there are major differences between the community-dwelling elderly (independent living) and those residing in nursing homes. Clearly, drug side effects, efficacy, absorption, and other factors may be markedly different between a 93-year-old healthy person living independently and a 68-year-old frail person residing in a nursing home. In addition, issues regarding health care delivery will likely differ between the community-dwelling elderly and the nursing home elderly. Studies should be designed with specific populations in mind, and reports should specify the populations studied.50

Diagnosis of Epilepsy in the Elderly

The diagnosis of epilepsy is difficult in the elderly. In the Veterans Administration (VA) study #428, a large portion of patients with epilepsy had been initially misdiagnosed.68 Other conditions such as cardiac insufficiency, metabolic conditions, convulsive syncope (micturition syncopy, cough syncope), and other conditions must be eliminated before it can be concluded that an event was an epileptic seizure. In the elderly, the most common identifiable cause of epilepsy is stroke, which accounts for 30% to 40% of all cases. Brain tumor, head injury, and Alzheimer’s disease are other major causes. However, in a large number of cases, the precise cause cannot be identified and the etiology is cryptogenic. Because most seizures in the elderly are caused by a focal area of damage to the brain, the most common seizure types are localization related. Complex partial seizures are the most common seizure type, accounting for nearly 40% of seizures in the elderly population.31 Both simple and complex seizures may spread and develop into generalized tonic–clonic seizures. All major AEDs have a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indication for use in the types of seizures encountered in the elderly.

Table 1 Categorization of the Elderly with Epilepsy | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Pharmacoepidemiology of Antiepileptic Drug Use in Elderly

Antiepileptic Drug Use in Community-Dwelling Elderly

The largest study of AED use in community-dwelling elderly in the United States was the VA study coordinated by Berlowitz.63,64 Of a total of 1,130,155 veterans of age 65 years and older identified from the national data base of 1997 to 1999, 20,558 (1.8%) were identified as having epilepsy by having an ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification) code representative of this condition. Approximately 80% were receiving one AED and 20% were being treated with two or more. Phenytoin was used as monotherapy by almost 70%, whereas phenobarbital was used as monotherapy by approximately 10%. Another 5% were using phenobarbital in combination, mostly with phenytoin. Carbamazepine was used by just >10%, and newer AEDs (gabapentin and lamotrigine) were used by <10%.63,64 (Levetiracetam was not available at the time of the survey.) Smaller studies in community-dwelling elderly non-VA patients have found a similar distribution of AED use, with phenytoin by far the most widely used AED in the United States in this population.

Antiepileptic Drug Use in Nursing Homes

As people age, their need for nursing home care increases due to greater frailty and disease. For patients aged 65 years and older, there is a lifetime risk of 43% to 46% of ever becoming a resident in a nursing home (NH).41,73 At any one time, 4.5% of the elderly U.S. population is residing in a NH.37 In any research concerning NHs, the distinction must also be made between residents and admissions. A resident cohort includes all residents in the facility at a specified time, which is usually a cross-sectional sample and consists of a mixture of newly admitted residents and others who have been in the NH for different periods of time. In contrast, an admission cohort includes all people admitted to a facility during a specified time period.26

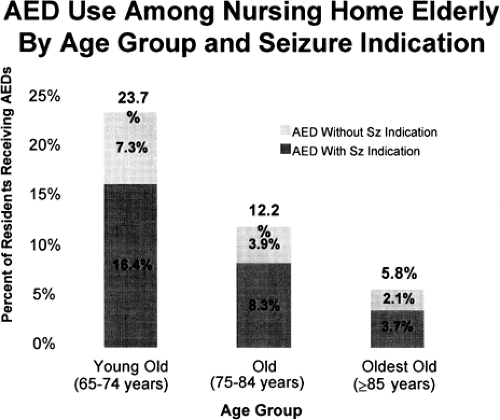

In a study of the residents residing in various nursing homes in the United States during the spring of 1995,25 the mean age of the 21,551 residents was 83.78 years (SD, 8.13 years). The age group distribution was young-old 15%, middle-old 36%, and old-old 49%. This distribution is similar to the population of 1,557,800 people ≥65 years of age in NHs in the year 2000, based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau.37 Of the residents in this NH sample, 10.5% had one or more AED orders on the study day, and 9.2% had a seizure indication (epilepsy or seizure disorder) documented in the chart. Phenytoin was used by 6.2% of the residents, followed by carbamazepine (1.8%), phenobarbital (1.7%), clonazepam (1.2%), valproic acid (0.9%), and all other AEDs combined (1.2%); these percentages exceed 10.5% due to AED polytherapy. Approximately 90% of AED use was for an epilepsy/seizure indication. If these results are extrapolated to all 1,557,800 elderly residents in U.S. NHs in 2000,37 then as many as 163,569 people were likely to have been receiving an AED. Of note, this prevalence is approximately five times that of AED use in the community.19,32 Age was inversely related to AED use. Of the young-old, 23.7% were prescribed an AED, with 16.4% for seizure indication and 7.3% for other. In the middle-old, 12.2% were prescribed an AED, with 8.3% for seizure and 3.9% for other; whereas the old-old had only 5.8% use, with 3.7% for seizure and 2.1% for other (Fig. 1). This finding was unexpected because of the upward curve in the incidence of epilepsy/seizure disorder with advancing age. Thus, one of the major findings of the study of AED use in U.S. nursing homes is that the young-old are three to four times more likely to be prescribed an AED than the old-old either prior to admission or after admission. Similar results were reported from a study in Italy.24

A study of admissions employing a longitudinal design to explore AED use at the time of admission used two study groups: (a) all persons aged ≥65 years admitted between January 1 and March 31, 1999, to one of the 510 Beverly Enterprises NH facilities in 31 U.S. states (N = 10,318) and (b) a follow-up cohort (n = 9,516) of those in the admissions group who were not using an AED at NH entry.26 This cohort was followed up for 3 months after their individual admission dates or until NH discharge, whichever occurred first. Approximately 8% (n = 802) of the admissions group used one or more AEDs at entry, and among these, greater than half (58%) had an epilepsy/seizure disorder indication. The AEDs used by newly admitted individuals with epilepsy/seizure disorder (n = 585) included phenytoin (n = 315; 54%), valproic acid (n = 57; 10%), carbamazepine (n = 52; 9%), and gabapentin (n = 27; 5%).

Among residents in the follow-up cohort in the same study (n = 9,516) who were not using an AED at admission, 260 (3%) were initiated on an AED within 3 months of admission. Factors associated with the initiation of AEDs during this period included epilepsy/seizure, manic depression (bipolar disease), age group, cognitive performance (Minimum Data Set Cognitive Score [MDS-COGS]), and peripheral vascular disease (PVD). Thus, many persons admitted without a diagnosis of epilepsy are diagnosed as such after entry, and the incidence of newly diagnosed epilepsy in the nursing home far exceeds that in other populations. A crude estimate is 600 in 100,000 per 3 months, or four to six times that reported for elderly community-dwelling elderly. The AEDs used by those in this group with an epilepsy/seizure indication were phenytoin 48%, valproic acid 8%, gabapentin 13%, carbamazepine 12%, and phenobarbital 7%; and the remainder others. There was also an inverse relationship between age group and initiation of an AED. Compared to the young-old, those in the old group (aged 75–84 years) were one third less likely to have an AED initiated (p < 0.05), and the oldest-old (aged ≥85 years) were only half as likely (p < 0.0001).26

Table 2 Frequency of Use of Comedications With Potential Pharmacokinetic or Pharmacodynamic Interactions With Antiepileptic Drugs in 4,291 Residents of Nursing Homes | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Clinical Pharmacology of Antiepileptic Drugs in the Elderly

The theoretical basis for age-related changes in drug pharmacokinetics was described many years ago but has not been widely applied to AEDs. Drug concentration at the site of action determines the magnitude of both desired and toxic responses. The unbound drug concentration in serum is in direct equilibrium with the concentration at the site of action and provides the best correlation with drug response.79 Total serum drug concentration is useful for monitoring therapy when the drug is not highly protein bound (<75%) or when the ratio of unbound to total drug concentration remains relatively stable. Three of the major AEDs (valproic acid, phenytoin, and carbamazepine) are highly bound, and binding is frequently altered.

The age-related physiologic changes that appear to have the greatest effect on AED pharmacokinetics involve protein binding and the reduction in liver volume and blood flow.29,69,78,80 Reduced serum albumin and increased α1-acid glycoprotein (AAG) concentrations in the elderly alter protein binding of some drugs.29,78,79 By age 65 years, many individuals have low normal albumin concentrations or are frankly hypoalbuminemic. Albumin concentration may be further reduced by conditions such as malnutrition, renal insufficiency, and rheumatoid arthritis. The concentration of AAG, a reactant serum protein, increases with age; further elevations occur during pathophysiologic stress such as stroke, heart failure, trauma, infection, myocardial infarction, surgery, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.78 Administration of enzyme-inducing AEDs also increases AAG.74 When the concentration of AAG rises, the binding of weakly alkaline and neutral drugs such as carbamazepine to AAG can increase, causing higher total serum drug concentrations and decreased unbound drug concentrations. Because of the complexity of confounding variables and the lack of correlation between simple measures of liver function and drug metabolism, the effect of age on hepatic drug metabolism remains largely unknown.17,18 Genetic determinants of hepatic isozymes may be more important than age in determining a person’s clearance.42

Renal clearance is the major route of elimination for a number of the newer AEDs. It is well known that an elderly person’s renal capacity decreases by approximately 10% per decade, but this also is highly dependent on the general state of health.

Despite the theoretical effects of age-related physiologic changes on drug disposition and the widespread use of AEDs in the elderly, few studies on AED pharmacokinetics in the elderly have been published. The reports generally involve single-dose evaluations in small samples of the young-old (65–74 years). There is a lack of data regarding AED pharmacokinetics in the oldest-old (>85 years), individuals who may be at greatest risk for therapeutic failure and adverse reactions.

Variability of Antiepileptic Drug Levels in Nursing Homes

Studies have shown that in compliant patients, the variability of AED concentrations over time is relatively small. One study

of phenytoin showed that in institutionalized patients, the variability between serial measurements over time was on the order of 10%. In the same study, compliant clinic patients had variability of approximately 20%.49 Approximately 5% of this can be accounted for by measurement instrument variability, although laboratories not following rigid quality control standards may have a much larger variability. The remainder of the variability arises from day-to-day alterations in absorption or metabolism or differences in AED dose content. The variability for carbamazepine and valproate is on the order of 25%, possibly due to their shorter half-lives and thus increased variability from sampling times.27 A small study found that phenytoin levels may fluctuate in the nursing home elderly.55 This was confirmed in an analysis of serial phenytoin levels from nursing home patients across the United States who had no change in dose, no change in formulation, and no additions of other medications.6 Some residents had a difference of two- to threefold from the lowest to the highest phenytoin concentrations. It is also interesting that some had very little fluctuation and were similar to the younger adults studied, as mentioned earlier. Similar but less severe fluctuations were observed for carbamazepine and valproate. These findings suggest that elderly frail nursing home residents may have great variability in absorption of drugs. Factors that contribute to this must be identified and strategies developed to minimize its effects.

of phenytoin showed that in institutionalized patients, the variability between serial measurements over time was on the order of 10%. In the same study, compliant clinic patients had variability of approximately 20%.49 Approximately 5% of this can be accounted for by measurement instrument variability, although laboratories not following rigid quality control standards may have a much larger variability. The remainder of the variability arises from day-to-day alterations in absorption or metabolism or differences in AED dose content. The variability for carbamazepine and valproate is on the order of 25%, possibly due to their shorter half-lives and thus increased variability from sampling times.27 A small study found that phenytoin levels may fluctuate in the nursing home elderly.55 This was confirmed in an analysis of serial phenytoin levels from nursing home patients across the United States who had no change in dose, no change in formulation, and no additions of other medications.6 Some residents had a difference of two- to threefold from the lowest to the highest phenytoin concentrations. It is also interesting that some had very little fluctuation and were similar to the younger adults studied, as mentioned earlier. Similar but less severe fluctuations were observed for carbamazepine and valproate. These findings suggest that elderly frail nursing home residents may have great variability in absorption of drugs. Factors that contribute to this must be identified and strategies developed to minimize its effects.

Clinical Trials of Antiepileptic Drugs in the Elderly

All major AEDs have an FDA indication for use for the seizure types most likely to be encountered in the elderly. However, there are few data relating specifically to these drugs in the elderly, and those that are available have been limited to community-dwelling elderly. One post hoc study of the VA cooperative study of carbamazepine and valproate found that elderly patients often had seizure control associated with lower AED levels than seen in younger individuals. However, side effects were also observed at levels lower than those seen in younger persons.65 A multicenter, double-blind, randomized comparison between lamotrigine and carbamazepine in elderly patients (mean age 77 years) with newly diagnosed epilepsy in the United Kingdom showed that the main difference between the groups was the rate of drop out due to adverse events, with a rate for lamotrigine of 18% compared to a rate of 42% for carbamazepine.11 The VA Cooperative Study #428, an 18-center, parallel, double-blind trial on the use of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine in patients 60 years or older, found that efficacy did not differ, but the main finding favoring the two newer AEDs was tolerability.68

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree