Eating, sleep, and sexual disorders

Eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS; atypical eating disorders)

Disorders of sexual function, preference, and gender identity

The drives to eat, sleep, and have sex can all be impaired or become otherwise dysfunctional in many psychiatric and medical disorders. They can also all be primary disorders, and it is the latter which are the focus of this chapter.

Eating disorders

Eating disorders are characterized by abnormalities in the pattern of eating which are determined primarily by the patient’s attitude to their weight and shape. The disorders share a distinctive core psychopathology which is best described as an over-evaluation of weight and shape, such that patients judge their self-worth in terms of their shape and weight and their ability to control these. The disorders covered in this chapter include anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa as well as a number of related conditions. Obesity is not covered, as it is not a psychiatric disorder (Marcus and Wildes, 2009), although it is associated with an increased risk of various psychiatric disorders (Petry et al., 2008).

Until the late 1970s, eating disorders were believed to be uncommon. Following the description of bulimia nervosa, they have increasingly been seen as conspicuous and disabling. It remains uncertain whether the rapid rise in presentation and diagnosis reflects a true increase in incidence or an increase in detection and diagnosis (Curren et al., 2005). Many eating disorders go clinically unrecognized, and it is estimated that only about 50% of the cases of anorexia nervosa in the general population are detected in primary care; for bulimia nervosa the figure is substantially less, and most individuals with bulimia are untreated.

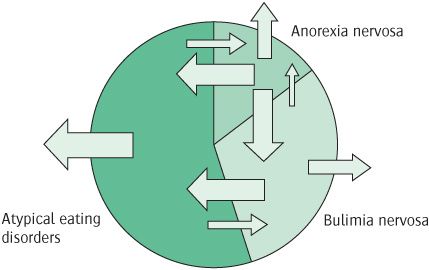

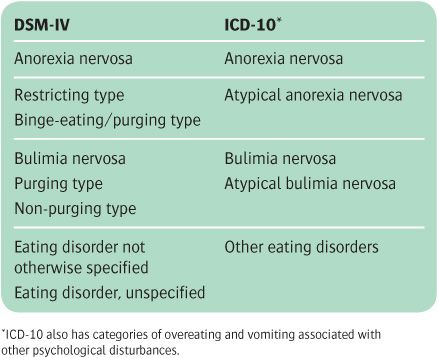

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are part of a larger range of eating disorders which include those that are clinically very similar to the two main diagnoses, but fail to meet their precise diagnostic criteria. These disorders are classified within DSM-IV as ‘Eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS).’ They are also known as atypical eating disorders, and in community samples are actually more frequent than either anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. In fact, many patients with EDNOS have previous histories of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, and some patients with EDNOS will eventually meet the criteria for one of the two latter diagnoses. The fact that patients with eating disorders tend to ‘migrate’ between these various diagnoses (see Figure 14.1) suggests that they all share a common pathophysiology, and that the boundaries between them are largely arbitrary (Fairburn and Harrison, 2003; see also Eddy et al., 2008). Despite these reservations about the current classification of eating disorders, this chapter will follow the standard terminology as used in DSM-IV and ICD-10 (see Table 14.1).

Figure 14.1 Schematic representation of temporal movement between the eating disorders. The size of the arrow indicates the likelihood of movement in the direction shown. Arrows that point outside of the circle indicate recovery. Reprinted from The Lancet, 361 (9355), Christopher G Fairburn and Paul J Harrison, Eating disorders, pp. 407–16, Copyright (2011) with permission from Elsevier.

Anorexia nervosa

Although there were many previous case histories, anorexia nervosa was first named in 1868 by the English physician William Gull, who emphasized the psychological causes of the condition, the need to restore weight, and the role of the family. The other key description at this time was by Charles Lasegue in Paris. The main features are very low body weight (defined as being 15% below the standard weight, or body mass index (BMI) of less than 17.5 kg/m2), an extreme concern about weight and shape characterized by an intense fear of gaining weight and becoming fat, a strong desire to be thin and, in women, amenorrhoea (for DSM-IV criteria, see Box 14.1).

Most patients are young women (see the section on epidemiology below). The condition usually begins in adolescence, although childhood-onset and older-onset cases are encountered. It generally begins with ordinary efforts at dieting, which then get out of control. The central psychological features are the characteristic overvalued ideas about body shape and weight (Fairburn et al., 1999a). The patient may have a distorted image of her body, believing herself to be too fat even when she is severely underweight. This belief explains why most patients do not want to be helped to gain weight.

The pursuit of thinness may take several forms. Patients generally eat little and set themselves very low daily calorie limits (often between 600 and 1000 kcal). Some try to achieve weight loss by inducing vomiting, exercising excessively, and misusing laxatives. Patients are often preoccupied with thoughts of food, and sometimes enjoy cooking elaborate meals for other people. Some patients with anorexia nervosa admit to stealing food, either by shoplifting or in other ways.

Table 14.1 Diagnostic classification of eating disorders

Binge eating. A subgroup of patients have repeated episodes of binge eating (uncontrollable overeating). This behaviour becomes more frequent with chronicity and increasing age. During binges, the patient typically eats foods that are usually avoided. After overeating they feel bloated and may induce vomiting. Binges are followed by remorse and intensified efforts to lose weight. If other people encourage them to eat, the patient is often resentful; they may hide food or vomit in private as soon as the meal is over. In DSM-IV, anorexia nervosa with binge eating and purging (self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives or diuretics) is recognized as a distinct type, which differs from the restricting type.

Amenorrhoea is one of several physical abnormalities that have traditionally been incorporated in diagnostic criteria. It occurs early in the development of the condition, and in about 20% of cases it precedes obvious weight loss, although careful history taking generally reveals that these patients had already started dieting. Some cases first come to medical attention with amenorrhoea rather than disordered eating.

Other symptoms. Depressive, anxiety, and obsessional symptoms, lability of mood, and social withdrawal are all common. Lack of sexual interest is usual. For a review of anorexia nervosa, see Russell (2009).

Physical consequences

A number of important symptoms and signs of anorexia nervosa are secondary to starvation. Several body systems can be affected (see Table 14.2). For a review of the physical consequences, see Mitchell and Crow (2006).

Epidemiology

Incidence. Estimates of the incidence of anorexia nervosa which are based on case registers in the UK and the USA range from 0.4 to 4 per 100 000 members of the population per year, but are much higher among young women (Keski-Rahkonen et al., 2007). Reported incidence rates increased from the beginning of the twentieth century up to the 1970s, but have probably remained fairly stable since then (Curren et al., 2005).

Prevalence. A large US community survey found a lifetime prevalence of 0.9% among women and 0.3% in men (Hudson et al., 2007), and a comparable Finnish study found a 2.2% prevalence in women, with 50% of cases unknown to services (Keski-Rahkonen et al., 2007). The gender difference is greater in clinical samples. The condition is more common in the upper than the lower social classes, and is reported to be rare in non-Western countries and in the non-white population of Western countries (Hoek and van Hoeken, 2003).

Aetiology

Genetics and neurobiology

Among the female siblings of patients with established anorexia nervosa, 5–10% suffer from the condition, compared with 0.5–1.0% of the general population of the same age. Siblings also have an increased risk of other eating disorders, suggesting a common familial liability. This increase in risk might be due to family environment or to genetic influences. A surprisingly large heritability (up to 75%) is reported in twin studies (Bulik et al., 2007a), although the figures have been questioned (Fair-burn et al., 1999b). Several genes have been implicated, including the 5-HT transporter (Lee and Lin, 2010), but most of the findings have not been well replicated, and a recent genome-wide study had no unequivocal positive findings (Wang et al., 2011). Neurobiologically, the focus is on alterations in neurotransmitter systems, such as changes in 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors (Kaye, 2008). However, it is often difficult to determine whether abnormalities are causal, or are the result of starvation and weight loss.

Social factors

The fact that anorexia nervosa is more common in certain societies suggests that cultural factors play a part in its development. Important among such factors is likely to be the notion that thinness is desirable and attractive. Surveys in more affluent societies show that most schoolgirls and female college students diet at one time or another. However, when other risk factors are taken into account, people who develop anorexia nervosa have no greater exposure to factors that increase the risk of dieting. This suggests that the problem is more due to how an individual reacts to dieting than to dieting itself.

Individual psychological causes

Bruch (1974) was one of the first writers to discuss the psychological antecedents of anorexia nervosa. She suggested that these patients are engaged in ‘a struggle for control, for a sense of identity and effectiveness, with the relentless pursuit of thinness as a final step in this effort.’ These clinical observations are supported by epidemiological studies, which implicate low self-esteem and perfectionism in the development of the disorder (Fairburn, 1999). It has been suggested that these premorbid personality traits can make it particularly difficult for an individual to negotiate the demands of adolescence.

Table 14.2 Main physical features of anorexia nervosa

Reproduced with permission from Fairburn and Harrison (2003).

Causes within the family

Disturbed relationships are often found in the families of patients with anorexia nervosa, and some authors have suggested that they have an important causal role. Minuchin et al. (1978) held that a specific pattern of relationships could be identified, consisting of ‘enmeshment, overprotectiveness, rigidity and lack of conflict resolution.’ They also suggested that the development of anorexia nervosa in the patient served to prevent dissent within the family.

Epidemiological studies suggest that people who develop anorexia nervosa are more likely than healthy controls to be exposed to a range of childhood adversities, including poor relationships with parents and parental psychiatric disorder, particularly depression. However, these risk factors are not specific to anorexia nervosa, but are found with equal frequency among people who subsequently develop other psychiatric disorders (Fairburn, 1999). It seems likely that these general risk factors interact with specific factors within the individual, such as perfectionism and low self-esteem, to increase the risk of developing anorexia nervosa.

Course and prognosis

In its early stages, anorexia nervosa often runs a fluctuating course, with exacerbations and periods of partial remission, and full recovery is not uncommon in cases with a short history. The long-term prognosis is difficult to judge due to incomplete follow-up, or because there may be normalization in weight or menstrual function but persistent abnormalities of eating habits and attitudes to weight and shape. One large population study found that about two-thirds of women with anorexia nervosa had largely or fully recovered at 5 years (Keski-Rahkonen et al., 2007).

There is a sixfold increase in mortality, due both to suicide and to natural causes (Papadopoulos et al., 2009), the latter reflecting the many medical complications of anorexia nervosa (see Table 14.2). The elevated mortality rate remains 20 years after first hospitalization. Reported poor prognostic factors include older age at onset, long history, premorbid personality problems, comorbid substance misuse, and childhood obesity.

Assessment

Most patients with anorexia nervosa are reluctant to see a psychiatrist, so it is important to try to establish a good relationship. This means listening to the patient’s views, explaining the treatment alternatives, and being willing to consider compromises. A thorough history should be taken of the development of the disorder, the present pattern of eating and weight control, and the patient’s ideas about body weight (see Boxes 14.2 and 14.3). In the mental state examination, particular attention should be given to depressive symptoms, as well as to the characteristic psychopathology of anorexia nervosa itself. More than one interview may be needed to obtain this information and gain the patient’s confidence. The parents or other informants should be interviewed whenever possible. It is essential to perform a physical examination, with particular attention to the degree of emaciation, cardiovascular status, and signs of vitamin deficiency. Other wasting disorders, such as malabsorption, endocrine disorder, or cancer, should be excluded. Electrolytes should be measured if there is any possibility that the patient has been inducing vomiting or abusing laxatives.

Evidence about treatment effectiveness

There is a lack of good evidence about treatment and management. In part, this reflects the wide range in severity and the difficulty of evaluating complex interventions. This means that many current views and treatment guidelines (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004a) depend upon clinical experience and opinion. Preventive treatments are also under investigation (Stice et al., 2007).

Psychotherapy

Family therapy has been advocated, reflecting the belief that family factors are important in the origins of anorexia nervosa. Various kinds of family therapy have been used, and it is unclear which of them is most effective. Systematic reviews suggest that there are some benefits in adolescents, but not in adults (Bulik et al., 2007b), with no clear advantages over individual treatments (Fisher et al., 2010).

Cognitive–behaviour therapy (CBT) has largely replaced psychodynamically oriented psychological treatments. Overall, there is modest evidence for its efficacy in reducing relapse rates in anorexia nervosa (Bulik et al., 2007b). The efficacy of conventional CBT is unproven with regard to initial weight gain (Bulik et al., 2007b), but a specifically tailored form of CBT has efficacy in weight restoration as well as in maintenance in eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa (Fairburn et al., 2009a).

Guidelines also suggest interpersonal therapy and cognitive analytic therapy for anorexia nervosa, but the evidence is limited (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004a).

Medication

Many patients have significant symptoms of depression, and SSRIs are sometimes used for this indication. However, medication is not a routine part of the treatment of anorexia nervosa, because of the lack of efficacy (Walsh et al., 2006; Bulik et al., 2007b), although one trial reported that olanzapine may aid initial weight gain (Bissada et al., 2008). The increased risks of medication side-effects or toxicity because of the low weight and medical complications of the disorder must also be borne in mind.

Management

Starting treatment

Success largely depends on establishing a good relationship with the patient. It should be made clear that achieving an adequate weight is essential in order to reverse the physical and psychological effects of starvation. It is important to agree a specific dietary plan, while emphasizing that weight control is only one aspect of the problem, and help should be offered with the accompanying psychological problems. Educating the patient and their family about the disorder and its treatment is important.

Place of treatment

Most cases may be treated on a day-patient or outpatient basis, ideally within a specialist eating disorder service. Admission to hospital is now unusual, but may be indicated if the patient’s weight is dangerously low, if there is a comorbid disorder (e.g. severe depression), if there is a high and acute suicide risk, or if outpatient care has failed.

Admission to a medical ward is appropriate if the main reason for admission is life-threatening consequences of weight loss, such as electrolyte disturbance, hypoglycaemia, or severe infection.

Compulsory treatment for anorexia nervosa is controversial both legally and ethically (see Chapter 4), and is rarely used.

Restoring weight

A reasonable aim is an increase of 0.5 kg a week, which will usually require an extra 500–1000 calories a day. The target weight usually has to be a compromise between a healthy weight (a BMI above 20 kg/m2) and the patient’s idea of what her weight should be. A balanced diet of about 3000 kcal should be taken as three or four meals a day. It is good practice to monitor the patient’s physical state regularly, and to prescribe vitamin supplements if indicated. It is also important to assess and modify other weight-reducing strategies that the patient may employ, such as over-exercising and laxative misuse.

For those who require inpatient treatment, there should be an understanding that the patient will stay in hospital until her agreed target weight has been reached and maintained and there is a comprehensive, mutually agreed treatment plan for subsequent outpatient care. Eating must be supervised by a nurse, who has three important roles—to reassure the patient that she will not lose control over her weight, to be clear about the agreed targets, and to ensure that the patient does not induce vomiting or take laxatives. Inpatient weight restoration usually takes between 8 and 12 weeks. Some patients demand to leave hospital before their treatment is finished, but with patience the staff can usually persuade them to stay. In the past, strict behavioural regimens were used, but these had no proven advantage and often appeared punitive.

For guidelines on the treatment of anorexia nervosa, see the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2004a), and see also Box 14.4.

Bulimia nervosa

The term bulimia refers to episodes of uncontrolled excessive eating, sometimes called ‘binges.’ As mentioned above, the symptom of bulimia occurs in some cases of anorexia nervosa. The syndrome of bulimia nervosa was first described by Russell (1979) in a highly influential paper in which he named the condition and described the key clinical features in 30 patients who were seen between 1972 and 1978. However, Russell’s cases also suffered from concomitant anorexia nervosa and were therefore unlike the cases that we now think of as bulimia nervosa. Thereafter the syndrome ‘bulimia’ was included in DSM-III, and it soon became evident that bulimia nervosa was common in the general population among people who did not have anorexia nervosa.

For a review, see Fairburn et al. (2009b).

The central features of bulimia nervosa are as follows:

1. an irresistible and recurrent urge to overeat

2. the use of extreme measures to control body weight

3. overvalued ideas concerning shape and weight of the type seen in anorexia nervosa.

Two subtypes of bulimia nervosa are recognized in DSM-IV (see Box 14.5). The purging type is characterized by the use of self-induced vomiting, laxatives, and diuretics to prevent weight gain. In the non-purging type, ‘purging’ symptoms do not occur regularly but the person uses other behaviours to avoid weight gain, such as fasting and excessive exercise. Patients with bulimia nervosa are usually of normal weight. Patients who are substantially underweight usually qualify for a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, which takes precedence. Most patients are female, and they often have normal menses.

Patients have a profound loss of control over eating. Episodes of bulimia may be precipitated by stress or by the breaking of self-imposed dietary rules, or may occasionally be planned. During the episodes large amounts of food are consumed, on average over 2000 kcal per episode (e.g. a loaf of bread, a whole pot of jam, a cake, and biscuits). This voracious eating usually takes place when the patient is alone. At first it brings relief from tension, but this is soon followed by guilt and disgust. The patient may then induce vomiting or take laxatives. There can be many episodes of bulimia and purging each day.

Depressive symptoms are more prominent than in anorexia nervosa, and are probably secondary to the eating disorder. A high proportion of patients meet the criteria for major depression. The depressive symptoms usually remit as the eating disorder improves. A few patients appear to suffer from a depressive disorder of sufficient severity and persistence to require treatment with antidepressant medication.

Physical consequences

Repeated vomiting leads to several complications. Potassium depletion is particularly serious, resulting in weakness, cardiac arrhythmia, and renal damage. Rarely, urinary infections, tetany, and epileptic fits may occur. The teeth become pitted by the acidic gastric contents in a way that dentists can recognize as characteristic.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of bulimia nervosa is around 1% among women aged between 16 and 40 years in Western societies (Hoek and van Hoeken, 2003). It is at least ten times less common in men. The dramatic increase in presentation and diagnosis seen in the UK in the early 1990s has been followed by stability or a modest decline. It is possible that the earlier increase represented increased rates of detection of relatively long-standing cases (Curren et al., 2005).

Onset and development of the disorder

Bulimia nervosa usually has an onset in late adolescence (i.e. several years later than anorexia nervosa). It often follows a period of concern about body shape and weight, and 25% of patients have a history of a previous episode of anorexia nervosa. There is usually an initial period of dietary restriction which, after a variable length of time, but usually within 3 years, breaks down, with increasingly frequent episodes of overeating. As the overeating becomes more frequent, the body weight returns to a more normal level. At some stage, self-induced vomiting and laxative misuse are adopted to compensate for the overeating. However, this may result in even less control of eating.

Aetiology

Like anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa appears to be the result of exposure to general risk factors for psychiatric disorder, including a family history of psychiatric disorder, especially depression and substance misuse, and a range of adverse childhood experiences. It used to be thought that sexual abuse was especially common, but the evidence now suggests that the rate is no higher than among those who develop other types of psychiatric disorder (Fairburn, 1999). Epidemiological studies also suggest that, unlike those with anorexia nervosa, patients with bulimia nervosa have increased exposure to factors that specifically promote dieting, such as childhood obesity, parental obesity, and early menarche. Perfectionism appears to be less of a risk factor than in anorexia nervosa (Fairburn, 1999).

The neurobiological and genetic contributions appear to be broadly similar to those described above for anorexia nervosa (Kaye, 2008; Fairburn et al., 2009b).

Course and prognosis

This is uncertain, as there have been few long-term studies. However, despite the original assertion by Russell (1979) that bulimia nervosa was an ‘ominous variant’, its outcome is clearly better in terms of both recovery and mortality (Keel et al., 2003). Nevertheless, even 5 to 10 years later between one-third and a half of individuals still have a clinical eating disorder, although in many of these cases it will take an atypical form (Fairburn et al., 2000).

No convincing predictors of course or outcome have been identified, although childhood obesity and low self-esteem may be associated with a worse prognosis (Fairburn et al., 2000).

Evidence about treatment effectiveness

There has been more research into the treatment of bulimia nervosa than into that of anorexia nervosa, and more evidence for effective psychological and pharmacological treatments (Shapiro et al., 2007). For some patients, guided self-help according to cognitive–behavioural principles may be sufficient, but for most patients formal treatment is indicated. For a review, see Fairburn et al. (2009b).

Psychotherapy

Both CBT and interpersonal therapy are effective in bulimia nervosa. Of those who complete treatment (about 20% drop out), 60% will have stopped binge eating, and there is an 80% reduction overall. Psychological aspects improve in parallel. Early response is a strong predictor of outcome. The effect is maintained, with low relapse rates seen over 12 months.

The most striking evidence in this field comes from a trial of a specifically tailored CBT-based approach (‘CBT-E’). In a relatively large study, CBT-E reduced or abolished core behavioural and psychological symptoms of eating disorders, and showed sustained efficacy, with over 50% of patients remaining essentially recovered at 5-year follow-up (Fairburn et al., 2009a). The treatment was delivered in two forms—a ‘simple’ intervention which focused solely on the eating disorder, and a ‘complex’ intervention in which personality, mood, and interpersonal issues were also addressed. The authors suggested that the simple treatment is the default version and widely applicable to bulimia nervosa (and other eating disorders), whereas the latter could be limited to individuals with additional psychopathology.

Medication

Antidepressants are effective, producing a reduction of about 50% in the frequency of binge eating, and cessation in 20% of cases. The onset is more rapid than in depression, but a higher dose may be needed (e.g. fluoxetine 60 mg daily). However, long-term data are less encouraging and show poor compliance. Anti-depressants should be viewed as second-line treatment if effective psychological treatment is available. The combination of the two treatments does not appear to offer any advantages.

Management

The management of bulimia nervosa is easier than that of anorexia nervosa because the patient is more likely to wish to recover, and a good working relationship can often be established. Furthermore, there is no need for weight restoration. It is necessary to assess the patient’s physical state and to measure electrolyte status in those who are vomiting frequently or misusing laxatives.

As with many common disorders, a ‘stepped-care’ approach appears to be the best way of providing appropriate care for large numbers of people with varying degrees of severity of disorder (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004a).

Step 1. Identify the small minority (less than 5%) of individuals who need specialist treatment because of severe depression, physical complications, or substance abuse that requires treatment in its own right.

Step 2. Offer guided cognitive–behavioural self-help as appropriate, using a self-help book and with the guidance of a non-specialist facilitator. Treatment usually takes about 4 months and requires eight to ten meetings with the facilitator. Such treatment is appropriate for primary care, and appears to lead to good progress in about one-third of patients.

Step 3. Patients who do not show benefit within around 6 weeks of commencing Step 2 require full CBT. In a minority of cases, where concomitant depressive symptoms are severe, it is worthwhile adding an antidepressant drug such as fluoxetine in doses of up to 60 mg daily. However, most depressive symptoms will resolve with successful psychotherapy.

Step 4. Patients who do not improve with CBT require comprehensive specialist reassessment. In some cases, measures to provide more intensive cognitive therapy or an antidepressant drug may be useful. It is important to review the initial treatment with the patient with the aim of agreeing a treatment approach that the patient finds acceptable (see Box 14.6).

Eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS; atypical eating disorders)

These DSM-IV and ICD-10 categories are for disorders of eating that do not meet the criteria for anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, but which are of clinical severity. As noted above, they are frequent, and are diagnosed in at least one-third of referrals when current diagnostic criteria are applied strictly.

Binge eating disorder

A subgroup within EDNOS, binge-eating disorder, is recognized in DSM-IV as ‘requiring further study.’ It is characterized by recurrent bulimic episodes in the absence of the other diagnostic features of bulimia nervosa, particularly counter-regulatory measures such as vomiting and purging. Patients may have depressive symptoms and some dissatisfaction with their body weight and shape; however, this is usually less severe than in bulimia nervosa. Binge eating disorder is of comparable chronicity and stability to other eating disorders (Pope et al., 2006).

The risk factors for binge eating disorder are similar to those for psychiatric disorder in general, and for obesity. About 25% of patients who present for treatment for obesity have features of binge eating disorder. The condition generally affects an older age group than bulimia nervosa, and up to 25% of those who present for treatment are men.

Unlike the other eating disorders described here, binge eating disorder has a high spontaneous remission rate and larger effect sizes for response to CBT, interpersonal therapy, and antidepressants (Vocks et al., 2010).

Psychogenic vomiting

Psychogenic vomiting is chronic and episodic vomiting without an organic cause, which commonly occurs after meals and in the absence of nausea. It should be distinguished from the more common syndrome of bulimia nervosa, in which self-induced vomiting follows episodes of binge eating (uncontrolled overeating). Psychogenic vomiting appears to be more common in women than in men, and usually presents in early or middle adult life. It is reported that both psychotherapeutic and behavioural treatments can be helpful.

For a review of idiopathic vomiting disorders, see Olden and Chepyala (2008).

Sleep disorders

Psychiatrists may be asked to see patients whose main problem is either difficulty in sleeping or, less often, excessive sleep. Many other patients also complain about sleep problems as one of their symptoms. However, sleep disturbances are often overlooked or misdiagnosed (Stores, 2007).

Sleep problems are important for several reasons.

• They may represent primary sleep disorders (which are the focus of this section).

• They may be causes of psychological symptoms.

• They may be symptoms of psychiatric disorder, especially mood disorders (see Chapter 10).

• Sleep problems can also occur in a range of medical disorders.

Many patients who sleep badly complain of tiredness and mood disturbance during the day. Although prolonged sleep deprivation leads to some impairment of intellectual performance and disturbance of mood, loss of sleep on occasional nights is of little significance except in those whose responsibilities or activities require maximum alertness. The daytime symptoms of people who sleep badly are probably related more to the cause of their insomnia than to insomnia itself.

For a review of the biology of sleep and its disorders, see Siegel (2009) and Stores (2009a).

Classification

Table 14.3 shows the DSM-IV classification of sleep disorders, which is compatible with the more elaborate International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Classification in ICD-10 is rather different, with sleep disorders occurring in three different parts of the classification.

Epidemiology

Sleep disorders are frequent, but there is a wide range of variation in estimates, depending on the definition and the population studied; for example, 22% of adults meet the DSM-IV criteria for insomnia, but only 4% meet the ICD-10 criteria (Roth et al., 2011). Excessive sleepiness occurs in 5% of adults, and possibly 15% of adolescents and 14% of the adult population have some form of chronic sleep–wake disorder.

In the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study (Ford and Kamerow, 1989), 10.2% of the community sample reported insomnia and 3.2% reported hypersomnia. In total, 40% of those with insomnia and 46.5% of those with hypersomnia had a psychiatric disorder, compared with 16.4% of those with no sleep complaints. Groups at particular risk of persistent sleep problems include young children, adolescents, the physically ill, those with learning disability, and those with dementia. Women have a higher rate of insomnia than men, across all conditions (Zhang and Wing, 2006). Ageing is associated with fragmentation and other changes in sleep patterns, and in the causes of sleep disorder (Wolkove et al., 2007).

Assessment

Assessment requires a full psychiatric and medical history, together with detailed enquiries about the sleep complaint (see Box 14.7). In some cases specialist investigation, including polysomnography, is necessary.

Table 14.3 Classification of primary sleep disorders in DSM-IV

Insomnia

Transient insomnia occurs at times of stress or as ‘jet lag.’ Short-term insomnia is often associated with personal problems—for example, illness, bereavement, relationship difficulties, or stress at work. Insomnia in clinical practice is usually secondary to other disorders, notably painful physical conditions, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders; it also occurs with excessive use of alcohol or caffeine, and in dementia. Sleep may be disturbed for several weeks after stopping heavy drinking. Sleep problems are also common in association with any medical illness that results in significant pain or discomfort or is associated with metabolic disturbances. They may also be provoked by prescribed drugs. In about 15% of cases of insomnia, no cause can be found (primary insomnia). People vary in the amount of sleep that they require, and some of those who complain of insomnia may be having enough sleep without realizing it. For a review of insomnia, see Sateia and Nowell (2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree