27 Endoscopic Cavernous Sinus Surgery

Giorgio Frank, Diego Mazzatenta, Vittorio Sciarretta, Matteo Zoli, Giovanni Farneti, and Ernesto Pasquini

Introduction

Introduction

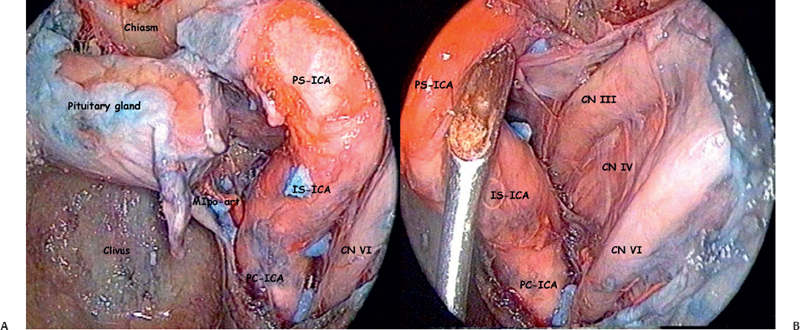

A single gold standard in cavernous sinus (CS) surgery does not exist, because the technique must be adapted to the features of the particular tumor. Anterior extracranial approaches and transcranial approaches are complementary, and both techniques facilitate obtaining the best surgical result with the minimal morbidity. Both have to be in the armamentarium of the skull base surgeon operating on CS tumors. Anterior extracranial approaches present three advantages over the transcranial approaches: (1) They are extracerebral, avoiding any brain manipulation. 2) They enable penetrating the CS through the medial wall, which is devoid of any nerves. Conversely, in transcranial approaches, the CS is penetrated, crossing the lateral wall through narrow windows between the cranial nerves. (3) Working within the CS in anterior extracerebral approaches, there are areas, such as the medial and the posterosuperior compartments, that do not run the risk of nerve damage, and there are others area, such as the anteroinferior and the lateral compartments, that have a well-defined point where there is a risk of nerve damage. The abducens nerve (cranial nerve VI) runs the main risk of damage because it runs free in the CS space; the others nerves are embedded and protected between the two layers composing the lateral wall of the CS (Fig. 27.1).

The main disadvantage of anterior extracerebral approaches is the difficulty of controlling the carotid artery and protecting it from injury. Jho and Carrau1 in 1997 reported the first series of pituitary adenomas treated using an endonasal endoscopic technique. Since that time, we have recognized the possibility of extending this technique to use it in surgery of the parasellar region. One year later we started our experience with endoscopic endonasal surgery of the CS, and our preliminary results were reported to the Fifth European Skull Base Society Congress in 2001.2 We prefer the endoscopic technique because it overcomes the limitations of the microsurgical technique,3 such as the necessity to utilize wider surgical channels with limited peripheral vision, and the necessity to utilize metallic retractors.

We recommend the endoscopic approach only to surgeons who are well trained with this technique and only in centers where endovascular support is available, and where it is possible to switch to open surgery, if needed.

Selection Criteria

Selection Criteria

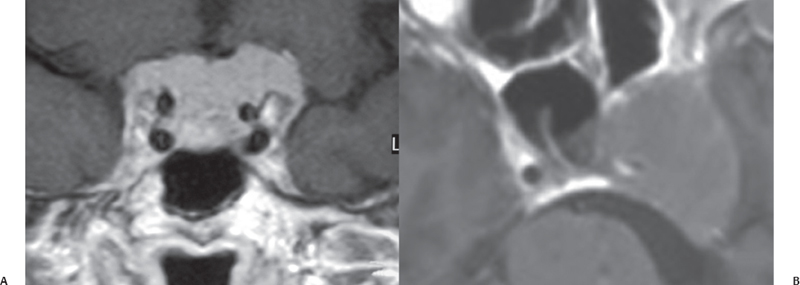

The selection criteria for an endoscopic CS surgery are mainly the biological behavior of the tumor and its location. Tumors involving the vessels and nerves, such as meningiomas and carcinomas, are not good candidates for this approach (Fig. 27.2). Conversely, tumors not involving the vessels and the nerves, such as adenomas and chordomas or chondrosarcomas, are amenable to this type of surgery. The consistency of the tumor may be a further criterion for selecting the endoscopic approach, with soft tumors being more suitable for this type of surgery. Only tumors that are totally extradural or have limited intradural extension are suitable for endonasal endoscopic approach. But if the tumor has a large intradural extension, we use the transcranial approach.

Technical Note

Technical Note

A detailed description of our endonasal approach to the CS is available elsewhere.4–7 In this chapter we focus on the tips and pearls that can result in a successful operation.

Fig. 27.1 Left cavernous sinus (CS) anatomical dissection in a venous and artery injected specimen. (A) The medial and posterosuperior compartments. The parasellar (PS-ICA) and infrasellar (IS-ICA) portion of the internal carotid artery delimit this area laterally. The postero inferior border of the medial compartment is the meningohypophyseal artery. No nerve crosses this area. The anteroinferior compartment is in front of the paraclival internal carotid artery (PC-ICA). Medially and inferiorly to the lower portion of the PC-ICA is the vidian artery (not visible in these images). Cranial nerve VI runs free into the lateral portion of the CS attached to the lateral wall of PC-ICA, in the medial to lateral and inferior to superior directions. (B) After the medial displacement of the PS-ICA and IS-ICA, the lateral compartment and posterosuperior compartment of CS are well viewed. All nerves (with the exception of cranial nerve VI) run embedded between the two layers of the lateral wall of CS: the endosteal layer medially and the meningeal layer laterally.

We recommend placing the patient in the semi-sitting position, which reduces the bleeding and enables the spontaneous outflow of blood, making the operatory field clearer and facilitating visual control of the surgical bed. The main risk of the semi-sitting position is an air embolism, but we have never observed an air embolism during the endoscopic endonasal procedure, even if we routinely apply a device necessary to detect a similar complication.

The mechanical holder maintains the position of the endoscope during the crucial phase of the procedure; it enables both surgeons to work bimanually, permitting safe and precise adjustments of the position of the optics, which is necessary to avoid instrument crowding and to provide the best vision of the surgical field (Fig. 27.3).

Fig. 27.2 Two cases of meningioma involving the CS. (A) First case: A coronal view demonstrates that both CSs are infiltrated and the ICAs are totally encased by meningioma. (B) Second case: An axial view demonstrates the right parasellar segment of the ICA being strangled by meningioma with a small lumen.