33 Endoscopic Surgery for Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Paolo Castelnuovo, Andrea Pistochini, Francesca Simoncello, Ignazio Ermoli, Andrea Bolzoni Villaret, and Piero Nicolai

Introduction

Introduction

Until the 1980s, the surgical technique for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) removal involved only external (transfacial and transcranial) approaches. Over the years, endoscopic endonasal surgery, introduced to treat inflammatory diseases of the nose and paranasal sinuses, gradually expanded its uses to include the removal of selected benign and malignant neoplasms, such as JNA.3–18 This was made possible since the late 1990s by better assessment of the lesion due to improvements in imaging techniques (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] and highly selective angiography), increased experience with embolization and endoscopic surgery, and the refinement of instrumentation.

Surgery is also considered an alternative therapy for JNA with intradural or intracavernous extension because of the possible complications of radiotherapy on intracranial structures and the side effects of chemotherapy.19

Indications and Contraindications

Indications and Contraindications

The classification used to preoperatively assess the extension of the lesion was proposed by Andrews and modified by Fisch (Table 33.1).20 Based on this classification, the possibility of performing a purely endoscopic approach is evaluated.

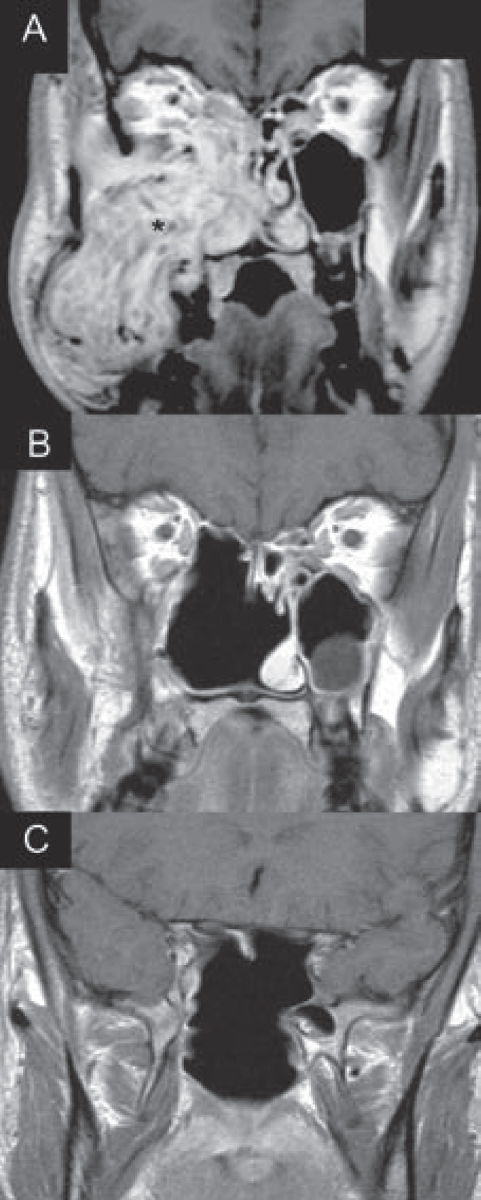

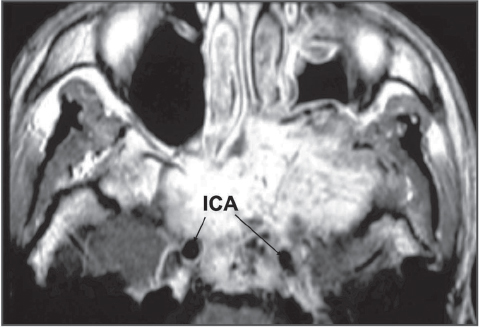

In the first years of our experience, only type I and type II were purely endoscopically treated, rarely type IIIa. In recent years, thanks to the evolution of the technique, it has been possible to remove also a small number of type IIIb JNAs. Contraindications for endonasal endoscopic surgery alone include type IV JNAs, the presence of residual lesions involving critical areas with significant scarring, such as the internal carotid artery (ICA), optic nerve, and cavernous sinus; the extension to soft tissues of the zygomatic region and cheek and associated with scarring from previous surgery (Fig. 33.1); tumor extension encasing the ICA (Fig. 33.2); and blood supply from important branches of the ICA (vidian and ophthalmic arteries). In these cases, and in the setting of greater tumor extension, the endoscopic endonasal approach can be used in combination with more aggressive external approaches.

| Type | Tumor Extent |

| I | Limited to the nasopharynx and nasal cavity, with bone destruction negligible, or limited to the sphenopalatine foramen |

| II | Invades the pterygopalatine fossa or the maxillary, ethmoid, or sphenoid sinus with bone destruction |

| IIIa | Invades the infratemporal fossa or the orbital region without intracranial involvement |

| IIIb | Invades the infratemporal fossa or orbit with intracranial extradural (parasellar) involvement |

| IVa | Intracranial intradural tumor without infiltration of the cavernous sinus, pituitary fossa, or optic chiasm |

| IVb | Intracranial intradural tumor with infiltration of the cavernous sinus, pituitary fossa, or optic chiasm |

Fig. 33.1 (A) A case in which the lesion involved the whole maxillary sinus with erosion of its lateral wall and extension to the subcutaneous layer of the cheek. In cases like this, the extension of the tumor can be easily removed from the nose with a purely endoscopic approach if the patient has not undergone previous surgery. In cases of recurrence, scarring will hinder the endoscopic resection, and a combined external approach (midfacial degloving) is required. Asterisk indicates the juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA). (B,C) Postoperative radiologic control (enhanced magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) after 1 year, showing the complete removal of the lesion.

Fig. 33.2 Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating the extension of the JNA from the pterygomaxillary region to include both cavernous sinuses, with tumor surrounding both paraclival tracts of the internal carotid artery (ICA) and also erosion of the clivus.

Diagnosis and Preoperative Workup

Diagnosis and Preoperative Workup

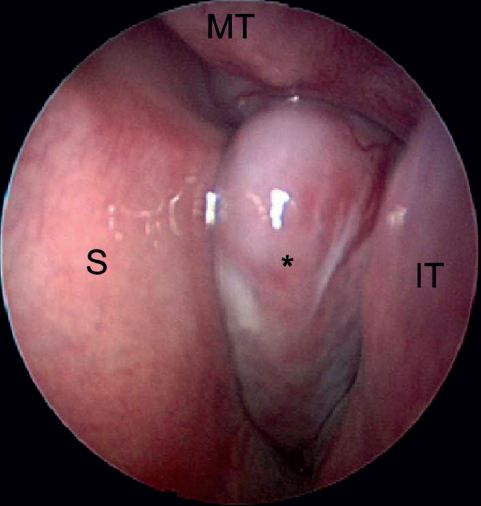

Diagnosis of JNA is made by the history, clinical features, and imaging findings. The lesion typically occurs in adolescent boys or young men complaining of nasal obstruction and epistaxis.20 Nasal endoscopy reveals a multilobulated, dusky red lesion occupying the nasal fossa and nasopharynx (Fig. 33.3). CT and MRI facilitate identification of the characteristic features. Thus, a biopsy of the tumor is considered unnecessary; it is also risky.21,22

Specific goals of imaging include confirmation of the diagnosis; definition of the extension of the lesion, with particular interest in the study of the orbital region, infratemporal fossa, and intracranial invasion (cavernous sinus, ICA, dura mater); and evaluation of bone erosion.19,23 Therefore, noninvasive imaging of JNA includes a bone window CT scan without contrast to look for bony modifications and an MRI with gadolinium to assess tumor enhancement, intralesional features, its relationship with perilesional soft tissues (periorbit, dura mater, ICA), and its extension.

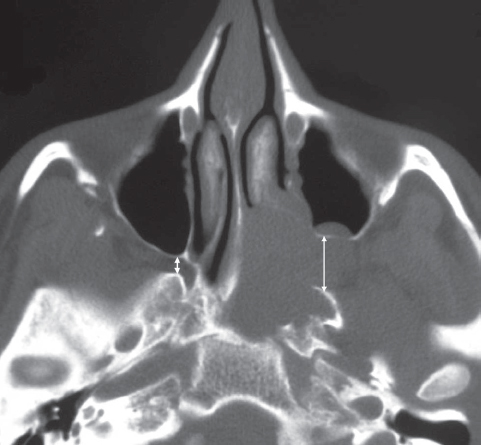

On CT the pathognomonic sign is the enlargement of the anteroposterior diameter of the sphenopalatine fissure in the axial view (Fig. 33.4), which is also evident in an early lesion. From this area, through the sphenopalatine foramen, the JNA spreads toward the nasal fossa or into the diploe of the pterygopalatine process or to the basisphenoid enlarging the vidian canal.24 The other important radiologic feature is the erosion of the base of the pterygoid process (Holman-Miller sign), which is evident in a coronal view (Fig. 33.5).25

The characteristic finding on MRI is the bright enhancement after gadolinium administration. The presence of high-flow vessels, characterized by the absence of signal (flow void), can give the lesion its typical heterogeneous appearance (bright-dark contrast) (Fig. 33.6).24

Fig. 33.3 Endoscopic endonasal image with a 0-degree endoscope showing a preoperative view of a JNA (asterisk) of the left nostril completely occluding the rhinopharynx. IT: inferior turbinate; MT: middle turbinate; S: septum.

Fig. 33.4 The pathognomonic sign of JNA on an axial computed tomography (CT) scan is the enlargement of the sphenopalatine foramen and the erosion of the basisphenoid, with eventual obliteration of the vidian canal. The two white arrows show the different anteroposterior diameters of the foramen in the presence of a left JNA.

Fig. 33.5 Coronal view CT scan showing the erosion of the base of the pterygoid process (Holman-Miller sign) in the white circle.