Case

Age/sex

Symptoms

Intradural/lateral extension

Prev. OP/RT

Extent of resection

Complication

Time to re-OP (mo)/extent of resection

Adjuvant RT

F/u (mo)

1

56/F

None

+/+

−/−

GTR

Transient CN VI palsy

42

2

62/F

CN VI palsy

−/−

−/−

GTR

None

11/ GTR

Heavy P

21

3

54/M

Transient dysarthria

+/−

−/−

GTR

CSF leakage

15

4

64/F

CN VI palsy

−/+

+/ Linac-SRT

GTR

CSF leakage

38/GTR

44

5

66/M

CN VI palsy

−/+

+/−

Subtotal

None

18/GTR

28

6

41/M

None

−/+

+/Heavy P

GTR

None

27

7

43/M

CN III palsy/hemiparesis

+/−

+/−

Subtotal

ICA injury

12/Subtotal

Gamma knife

21

29.4 Representative Cases

29.4.1 Tumor with Lateral Extension

This 64-year-old woman was operated upon her clival chordoma 15 years ago with the microscopic transsphenoidal surgery. Since then she received tumor removal three times for the recurrent tumor, the last of which being the endoscopic transnasal approach for the left petrous apex lesion 38 months ago with gross total removal. She developed abducens nerve paresis at the contralateral side to the previous surgery. The MRI revealed small recurrent tumor at the right petrous apex behind the paraclival carotid artery (Fig. 29.1 upper row). The repeat tumor removal through the endoscopic transnasal approach was performed. After the scar tissue within the sphenoid sinus is removed, the medial compartment of the tumor became visible, but the major compartment was still obscured by the paraclival carotid artery. Only after application of the 30- and 70-degree side-viewing lenses, the tumor could be visualized and dissected with the curved instruments until the bottom of the tumor bed (Fig. 29.2). Gross total removal was finally achieved without complication which was confirmed on postoperative MRI (Fig. 29.1 lower row). As the patient had been irradiated soon after initial previous surgery, and as this last recurrence is not in continuity with the lesion removed in previous endoscopic surgery, the application of additional radiation therapy was withheld. She is being followed up closely with MRI and is recurrence free for 5 months.

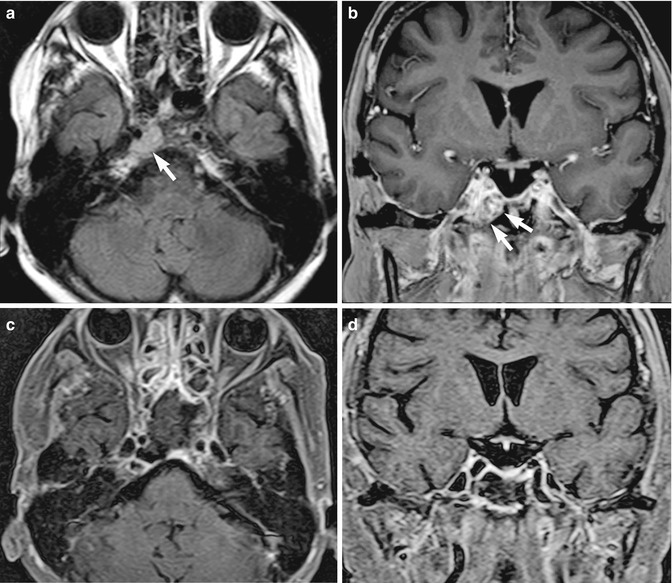

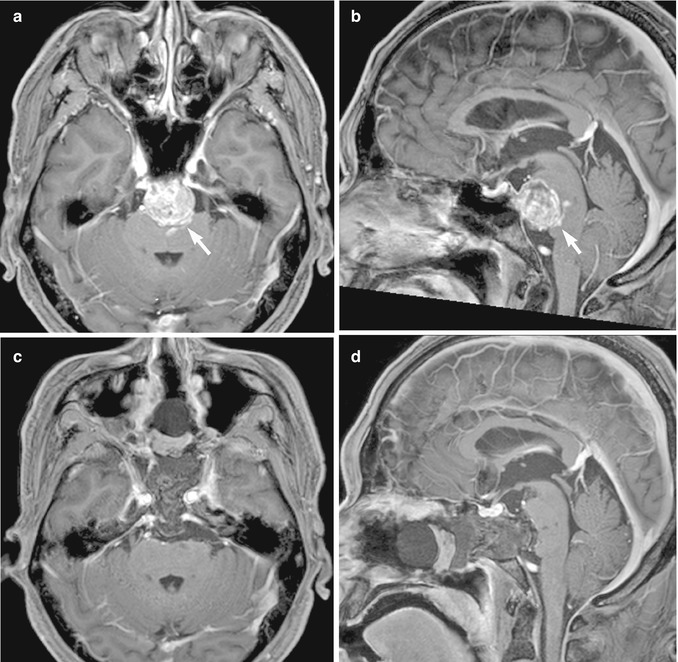

Fig. 29.1

The pre- and postoperative MRIs of a patient with recurrent clival chordoma. The tumor is demonstrated as a high-intensity lesion on preoperative axial FLAIR image at the right upper clivus behind the paraclival carotid artery (upper left, white arrow). The coronal T1-weighted image demonstrated inhomogenous enhancement of the tumor by the Gd-DTPA (upper right, white arrows). Gross total removal of the tumor through the endoscopic transnasal approach is confirmed on postoperative fat suppression T1-weighted Gd-enhanced axial and coronal images (lower row)

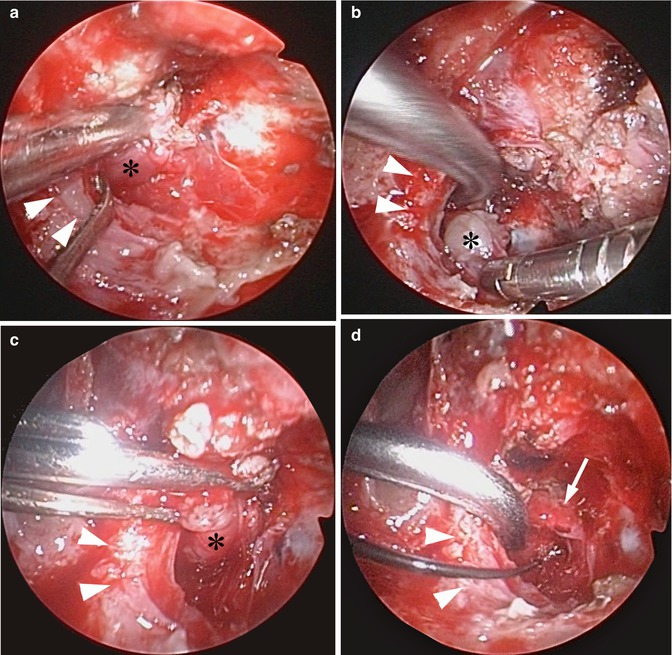

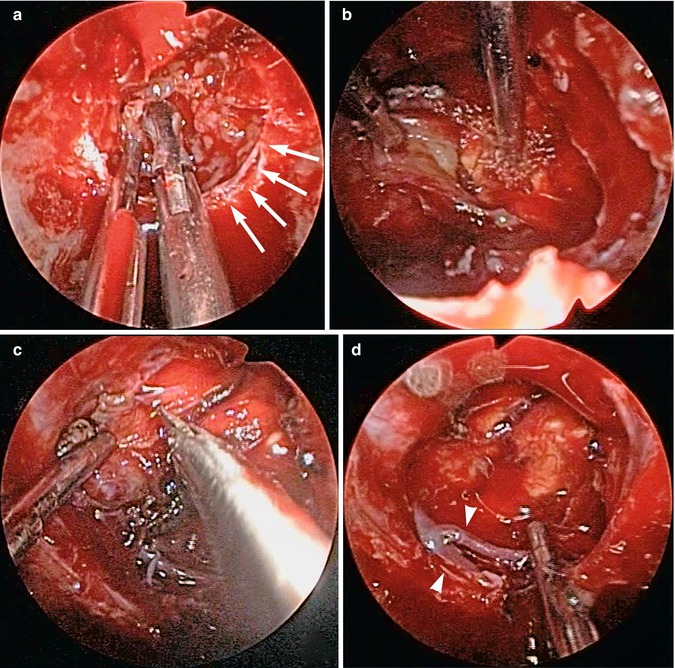

Fig. 29.2

Intraoperative photographs of tumor removal in the patient with recurrent clival chordoma presented in the Fig. 29.1. The tumor dissection is started with the 30° side-viewing endoscope in the space behind the paraclival carotid artery at the petrous apex using curved and steerable instruments (a, b). By introducing the 70° endoscope, the dissection plane between the carotid artery and the tumor is demonstrated more clearly and becomes visible down to the bottom of the tumor bed (c). This enhances the certainty and safety of the dissection maneuver with bended malleable dissector. The tumor bed is inspected with 70° side-viewing endoscope confirming gross total removal of the tumor (d). Arrowheads paraclival internal carotid artery; * tumor; arrow Dorello’s canal

29.4.2 Tumor with Prominent Intradural Extension

This 54-year-old man experienced transient dysarthria, for which an MRI study was performed. The result revealed a tumor at the mid-clivus with prominent intradural extension (Fig. 29.3 upper row). The lesion was considered as an indication for surgery through an endoscopic transnasal approach. After wide sphenoidotomy was performed, the middle portion of the clivus was exposed. Soon after starting with the drilling of the clival bone, the tumor was encountered, of which the major component penetrated the clival dura (Fig. 29.4a). The tumor was debulked and freed from adhesions to the brain stem with meticulous surgical maneuver comparable to those performed during the open microsurgery resulting in gross total removal (Fig. 29.4b–d). The dural defect was reconstructed with abdominal fat and fascia as an inlay graft, which was covered by the nasoseptal flap as an onlay graft. The fibrin glue was sprayed and the whole was reinforced with the balloon placed within the sphenoid sinus. The patient recovered without any neurological sequela and is without any evidence of tumor recurrence during the follow-up of 15 months (Fig. 29.3 lower row). Administration of adjuvant radiation therapy is being deferred.

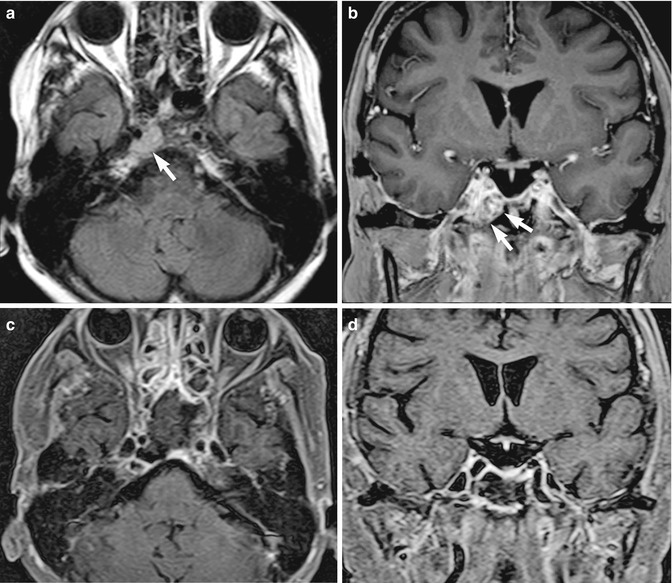

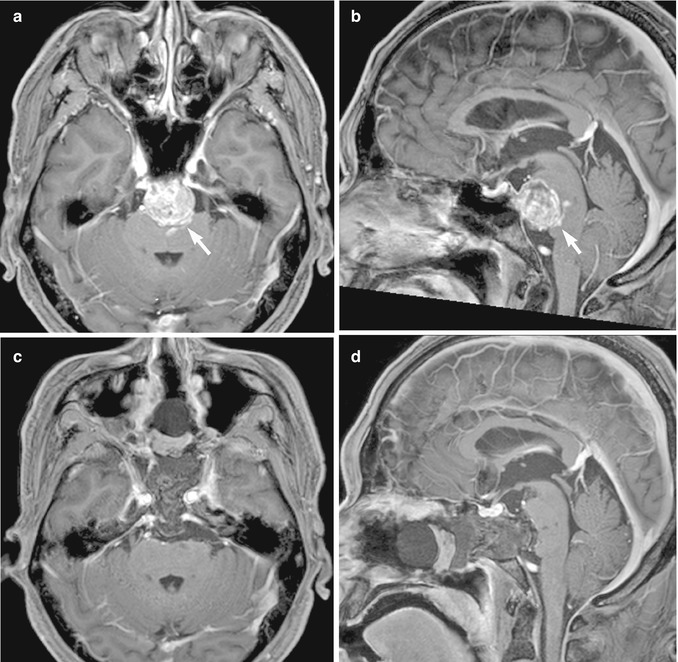

Fig. 29.3

The pre- and postoperative MRIs of a patient with a newly diagnosed clival chordoma. The tumor is demonstrated as an inhomogenously enhanced mass with marked intradural extension in preoperative axial and sagittal Gd-enhanced MR images (upper row). Note the signal intensity change in the brain stem suspicious of a manifestation of an adhesion (white arrow). The postoperative fat suppression T1-weighted Gd-enhanced axial and sagittal images demonstrated gross total removal of the tumor (lower row)

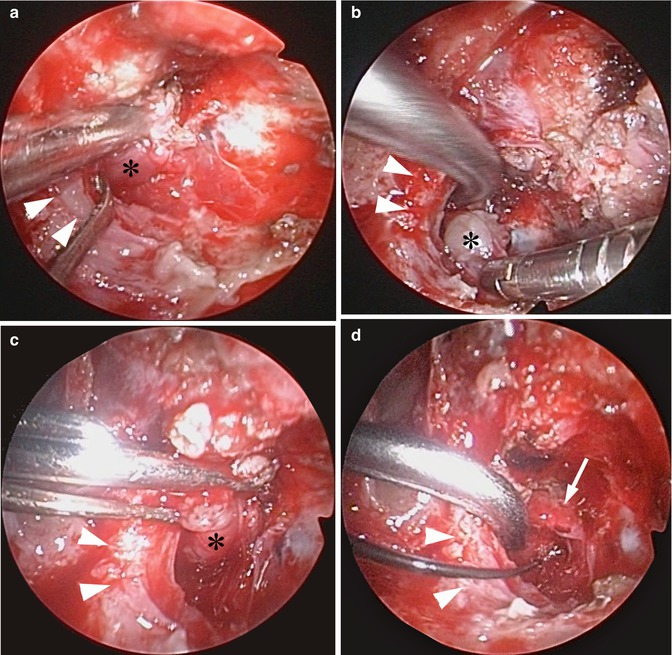

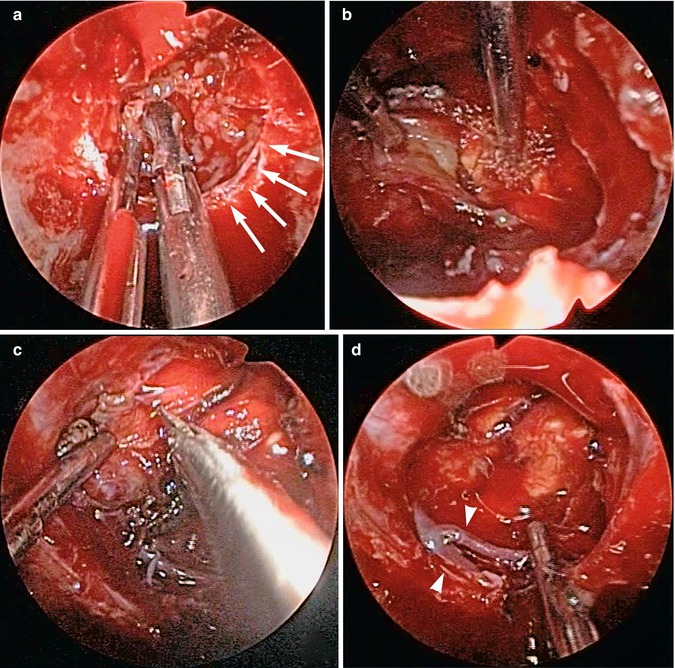

Fig. 29.4

Intraoperative photographs of tumor removal in the patient presented in the Fig. 29.2. The tumor with marked penetration of the clival dura is exposed and debulked with forceps (a). The tumor demonstrates tight adhesion to the brain stem, which is being meticulously dissected using blunt (b) and sharp (c) techniques, which are analogous to those performed during open microsurgery. After gross total removal, the large dural defect is present (d), which is subsequently reconstructed with vascularized pedicled nasoseptal flap. Arrows site of dural breach; arrowheads basilar artery and anterior inferior cerebellar artery

29.5 Literature Review

The surgical results of the pure endoscopic surgery were compared with those of the microscopic surgical series published in the same time period. Only literatures with sufficient data about the extent of tumor removal, recurrence-free period, overall survival rate, and patient status at the last follow-up were included. If multiple literatures were available from the same group, the latest was picked up. The literatures containing endoscope-assisted cases and in which the result of the endoscopic cases cannot be differentiated from the microscopic cases were excluded. The literatures included for the comparative analysis are listed in Table 29.2 for endoscopic and in Table 29.3 for microscopic surgical series. The mean gross total removal rate of the clival chordomas by the pure endoscopic transnasal approach was 65.6 % +/−21.6 [1, 2, 4, 6–8, 10, 11, 14, 18], which was significantly different to the results of the microscopic surgical series (40.8 % +/−27.2, P = 0.0476) [3, 9, 17, 19–21, 24, 25]. As the number of patients in each endoscopic series was rather small and the follow-up period short, the recurrence-free survival was computed by including all the available endoscopic cases in one group (Fig. 29.5). According to the Kaplan-Meier curve, the 3-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) of the endoscopic cases was 65.9 %, which was slightly higher compared to the results of the microscopic series (29.3–61.5 %). The long-term survival rate for the endoscopic cases was not imponderable due to the short follow-up period in most of the literatures. Comparison of the surgical complications demonstrated higher incidence of postoperative CSF leakage in the endoscopic series (13.2 +/− 13.2 vs. 5.8 +/− 6.4, P = 0.2661) though it was statistically not significant. In contrast, the occurrence of the permanent cranial nerve palsies was significantly higher in the microscopic series (1.6 +/− 3.3 vs. 14.5 +/− 11.1, P = 0.0059). There were only sporadic data as to the occurrence of severe complications, which were not detailed enough to compare both groups statistically. However, the KPS at the last follow-up was also significantly better in the endoscopic series (95 +/− 1.7 vs. 79.4 +/− 11.1, P = 0.0473).

Table 29.2

Literature list of the endoscopic surgical series

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree