10 Endoscopically Assisted Bimanual Operating Technique

Daniel B. Simmen, Hans Rudolf Briner, and Nick Jones

Introduction

Introduction

Today, endoscopic surgery of the paranasal sinuses is among the most frequently performed rhinosurgical procedures. It can be an effective solution in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis who have responded poorly to medical therapy.1 The indications for endoscopic surgery of the paranasal sinuses have been constantly expanding, so much that even complex procedures of the frontal sinuses and anterior skull base can now be performed endoscopically. Besides inflammatory diseases, the range of indications has expanded to include the removal of benign and malignant tumors.

Basic Principles of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

Basic Principles of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

Diseases of the paranasal sinuses are common and may seriously affect the patients’ quality of life. With an incidence of 3 to 5%, chronic rhinosinusitis is the most prevalent disease.2 Many patients with chronic rhinosinusitis often show an inadequate response to pharmacologic therapy. Endoscopic surgery of the paranasal sinuses offers an effective therapeutic option in these cases. As a result, endoscopic sinus surgery is now among the most widely practiced rhinosurgical procedures. Since endoscopic sinus surgery was first described over 30 years ago, we have witnessed impressive advances in operating techniques. Better endoscopes, better video cameras, and improved operating instruments have made it possible to view all of the paranasal sinuses and perform surgical procedures through the natural nasal orifice.3,4 The indications for endoscopic sinus procedures are constantly being expanded. Today even complex procedures of the lateral nasal wall and frontal sinus are performed endoscopically as well as specific operations of the anterior skull base, clivus, through the sphenoid sinus, and intracranially can be performed endoscopically. Besides inflammatory conditions, the range of indications has expanded to include the removal of benign and malignant tumors.

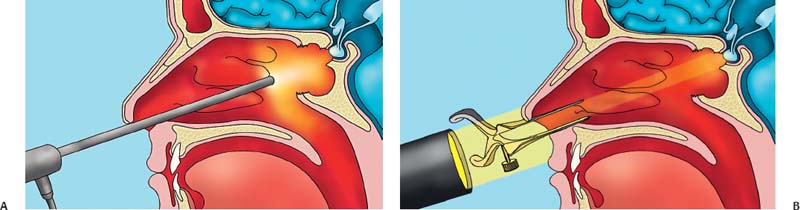

In the classic technique, the surgeon holds the endoscope in one hand and uses the other hand to perform the operation.5–7 This one-hand technique has its limitations. It is particularly difficult to remove bone and tumor tissue and control bleeding with just one hand.8,9 These difficulties have engendered a need for endoscopic surgeons to use both hands while operating. In this bimanual technique an assistant holds the video endoscope, thus freeing both of the surgeon’s hands so that he or she can deal more effectively with the challenging situations that arise in endoscopic operations (Fig. 10.1). The assistant is responsible for directing the endoscope and keeping a steady image of the operative field displayed on the video monitor. This technique differs from procedures done under a microscope. Although the microscope enables surgeons to operate with both hands, the endoscopic technique is advantageous in that it provides a close-up, dynamic view of all the paranasal sinuses. It also eliminates the problem of a loss of light caused by instruments in the path of the microscope light beam, because the endoscopic light source is always “on site.” The endoscopically assisted bimanual technique thus combines the advantages of the endoscopic technique with the key advantages of the operating microscope the ability, namely to operate with both hands (Fig. 10.2). The endoscopically assisted bimanual technique was first described by May et al in 1990. Despite the advantages of the bimanual technique, the classic one-hand technique is still more widely practiced. A major reason for this is the fact that the bimanual technique requires an extra assistant. Technical advances such as shaver technology and instruments with built-in suction channels have also made it easier to operate with one hand. However, the advantages of the bimanual technique, especially the improved visualization of the operative field owing to the constant presence of a suction tip, make it possible to perform more complex procedures on the paranasal sinuses with greater safety and precision. This particularly applies to the more severe forms of chronic rhinosinusitis with polyposis. The bimanual technique is also advantageous for revision procedures, tumor resection, and skull base and brain surgery. Moreover, a recent study has documented a reduction in operating time when the bimanual technique is used.10 The shorter operating time lead to lower costs, and this saving more than offsets the added costs for the extra assistant. Complex endoscopic skull base surgery and surgery of the brain would not be possible without this bimanual assisted technique.

Fig. 10.1 In the bimanual technique an assistant holds the video endoscope, thus freeing both of the surgeon’s hands.

Advantages of the Endoscopically Assisted Bimanual Operating Technique

Advantages of the Endoscopically Assisted Bimanual Operating Technique

Operating with Both Hands

In the endoscopically assisted bimanual technique, the assistant holds and directs the endoscope with the attached video camera. The image is transmitted to a video monitor. The surgeon watches the monitor and has both hands free for manipulating the surgical instruments (Fig. 10.3). This re-creates the feel of two-hand open surgery that is already familiar to most surgeons, meaning that established operating skills can be transferred to endoscopic skull base procedures.

Suction Tip Stays in the Operative Field; Fewer Instrument Changes

Surgical procedures on the paranasal sinuses can cause relatively heavy bleeding, which may obscure the surgeon’s view of the operative site. Clear visualization of the operative site is essential for anatomical orientation, and therefore the extravasated blood should be removed as rapidly as possible. In the classic one-hand technique, the surgeon must pull out frequently and exchange the operating instrument for a suction tip. These frequent instrument changes not only prolong the operation but also increase the likelihood that the distal lens of the endoscope will become soiled or smeared. With the bimanual technique, the surgeon can keep the suction tip in the operative field at all times while having the other hand free for cutting tissue. In this way the operative field remains largely free of blood, resulting in better visualization and anatomical orientation and less frequent instrument changes. This is the major reason why the operating time is approximately 20% shorter with the bimanual technique than with the one-hand technique. The ability to keep the suction tip in the operative field also facilitates bone removal with a drill or burr. The suction tip can provide a constant removal of irrigating fluid during drilling, thus maintaining a clear view of the operative site and causing less compromise of endoscopic vision by the irrigating fluid.

Fig. 10.2 The endoscopically assisted bimanual technique combines the advantages of the endoscopic technique with the key advantage of the operating microscope, namely the ability to operate with both hands. The endoscope facilitates bringing the optical device very close to the operating field with optimal image and light quality (A), whereas the microscope has only a straight channel for the optical visualization and loses some light at the entrance into the nostril (B).