CHAPTER 377 Endovascular Hunterian Ligation

Hunterian ligation refers to one of the oldest successful interventions for arterial aneurysms—ligation of the femoral artery to treat a popliteal aneurysm by John Hunter in 1785.1 Recently, the development of endovascular techniques has made it possible to completely occlude an artery intra-arterially, without the need for surgical access. Because refinements in the coiling technology used to treat cerebral aneurysms have continued to broaden the scope of intracranial aneurysms that can be repaired by coiling, hunterian ligation is more frequently relied on as a last resort to treat only the most surgically inaccessible and difficult aneurysms. Historically, hunterian ligation has referred to the permanent sacrifice of a parent artery to prevent access of blood to the aneurysm. This technique has also been referred to as “deconstructive” therapy, in contrast to “reconstructive” therapy, which refers to the targeted occlusion of a vascular abnormality without impairment of blood flow in the parent vessel. Hunterian ligation most often targets complex aneurysms, but sacrifice of the parent artery has also been used for the treatment of a wide range of neurosurgical entities, including hemorrhagic stroke, vascular tumors, arteriovenous malformations, fistulas, and arterial dissections.

History

John Hunter’s arterial sacrifice was first applied to the cerebral vasculature in 1804 by Abernethy as he unsuccessfully attempted to ligate the carotid artery in a case of posttraumatic dissection of the carotid artery. His pioneering attempt resulted in stroke, thus leaving the first successful carotid ligation to Astley Cooper in 1808. Only a year later, Victor Horsley successfully ligated the common carotid to treat a giant internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysm. Carotid ligation, either common or internal, was a common form of treatment of ruptured aneurysms until the late 1960s.1 Various methods of occlusion were used (gradual or abrupt). In addition, special clamps were developed that allowed treatment in the awake state so that if neurological impairment occurs with gradual occlusion, flow could be restored rapidly.1–4 In retrospect, by today’s standards, carotid ligation appears to be an inelegant treatment. Nevertheless, it was found to be effective in preventing rebleeding over the short term (6 months) in a randomized trial comparing abrupt common carotid occlusion with bed rest in patients with a ruptured posterior communicating aneurysm.3 Subsequently, long-term (≈10 years) follow-up of these patients revealed that the protection against rebleeding was lost; both ligated and bed-rested patients had the same rebleeding rate.5

Intracranial access would have to wait, however, until neurosurgical techniques dramatically improved, and it was not until 1945 that Poppen became the first to document ligation of the vertebral artery to treat an aneurysm. In 1962, the basilar artery was ligated proximally by Mount and Taveras.6 Without the ability to predict which patients could tolerate proximal arterial occlusion, however, favorable outcome was a matter of chance. Development of the Drake tourniquet permitted the surgeon to temporarily occlude an artery the day after surgery, when the patient had fully recovered from anesthesia, and therefore observe whether sacrifice of the parent vessel could be tolerated. Drake’s original study of occlusion of the basilar or vertebral artery in 14 patients was strikingly successful in that 7 of these patients did well.7 Surgical hunterian ligation, however, is limited by surgical access and was slowly replaced by reconstructive techniques for most intracranial aneurysms. Since the development of endovascular balloons in the early 1990s, parent vessel occlusion has become possible through transfemoral access, ironically the same vessel that Hunter first ligated in 1785. Further development of endovascular coils has increased the efficacy and expanded the indications for endovascular permanent occlusion (PO).

Indications

Endovascular hunterian ligation is reserved primarily for giant and fusiform aneurysms. Certain traumatic pseudoaneurysms and infectious aneurysms in which the risk associated with endovascular intervention is high may also be good candidates.8 The most complex aneurysms cannot be treated either by conventional surgical clipping or by endovascular coiling, which makes the technique, as well as the evidence supporting its practice, based predominantly on observational data from case series and individual reports.8 Although it would be ideal to exclude the lesion from the cerebral circulation and maintain blood flow through the parent artery, such reconstructive methods cannot be used for all aneurysms because of their shape and location. Surgeons have observed that as many as two thirds of giant intracranial aneurysms may not be amenable to clip reconstruction or endovascular treatment as a result of the location of the aneurysm or its morphology.7 This number, however, continues to shrink because of improving endovascular technology. The major treatment question when considering endovascular hunterian ligation is whether to perform an arterial bypass before permanent vessel occlusion. The current standard of care requires preoperative evaluation with balloon test occlusion (BTO) followed by distal perfusion.

Approaches to the Occlusion of Specific Cerebral Vessels

The Internal Carotid Arteries

As described earlier, the carotid arteries were the first cerebral vessels to be intentionally and successfully ligated in 1808 by the English surgeon Astley Cooper. Because of the surgical inaccessibility of portions of its course and the robust circulation of the circle of Willis, the ICA is the vessel most commonly treated with PO. PO is predominantly performed for lesions of the ICA itself, but it may be done for complex lesions of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) or middle cerebral artery (MCA) as well. O’Shaughnessy and colleagues, in their description of 58 PO procedures performed on the ICA over a period of 15 years, included aneurysms in multiple locations: 40 intracavernous, 5 petrous carotid, 3 cervical carotid, and 10 ophthalmic segment aneurysms.8 BTO was used in all cases, and EC/IC bypass was performed when deemed necessary after testing. Outcomes were reported at a mean follow-up of 76 months, with three patients dying during treatment, transient ischemia developing in six, delayed infarction developing in two, and the aneurysms of one patient enlarging after endovascular occlusion and requiring surgical clipping.

Certain types of aneurysms generally elude coiling by current technology and require PO as a last resort. In 2007, Park and coauthors reported 12 patients with blood blister aneurysms of the ICA, 7 of whom were treated with conventional endovascular coiling or stent-assisted coiling and 5 treated with BTO and endovascular trapping, which consists of permanent parent vessel occlusion both proximally and distally to prevent arterial backflow.9 The 7 patients treated with coiling demonstrated aneurysm regrowth, and 3 suffered rebleeding with severe morbidity. All 5 patients treated with PO had an excellent neurological outcome. With appropriate neurological testing, PO of the ICA can be an important treatment modality that may even be the preferred intervention in selected cases.

Recent studies have evaluated a new endovascular device, the Amplatzer vascular plug, for performing ICA parent vessel occlusion.10–12 The vascular plug is a self-expanding nitinol wire mesh that can be used in conjunction with coiling to act as an anchor on which the coil can be deployed. Preliminary studies have shown success in treating patients with this device for aneurysms in the cavernous portion of the ICA, cavernous carotid fistulas, and vertebral artery aneurysm at the origin of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA). Further studies are needed to evaluate this device and others in development that facilitate endovascular vessel occlusion.

The Vertebrobasilar Circulation

Ligation of the vertebrobasilar circulation for a known vertebral artery lesion appears to have first been performed by Poppen in 1945.13,14 Vertebral artery ligation, both unilateral and bilateral, was used by Drake in 1975 to treat large vertebral or basilar artery aneurysms in 14 patients.7 With stricter patient selection and the development of endovascular techniques, patient outcomes have improved significantly enough to justify vertebral artery PO in the proximal posterior circulation.

In 1991, Aymard and associates reported unilateral or bilateral endovascular hunterian ligation of the vertebral artery in 21 patients: 13 showed complete neurological recovery, 6 had partial aneurysm thrombosis, 1 had no thrombosis, 1 died, and 1 suffered a transient stroke.15 Because of this high rate of morbidity and mortality, the authors advocated strict preoperative CRT. An important contribution of this study was that the authors noted that in most cases, occlusion of the vertebral artery was most effective at the level of C1 because antegrade collateral flow is possible through the external carotid artery.16 It is important to note, however, that too much collateral flow can prevent aneurysmal thrombosis. Halbach and coauthors published a series of 15 patients who underwent proximal PO for vertebral artery vascular pathology and had improved outcomes.17

Collateral backflow from the opposite vertebral artery and the circle of Willis makes endovascular trapping an attractive treatment option for vertebral artery lesions.18,19 Double microcoil trapping after BTO of the vertebral artery proximal to the aneurysm was performed on 11 patients suffering SAH from dissecting vertebral artery aneurysms. As previously mentioned, this technique simultaneously occludes the parent vessel proximal and distal to the vascular lesion. The case series of 11 patients by Kai and colleagues reported good neurological outcome with only one transient adverse result.19

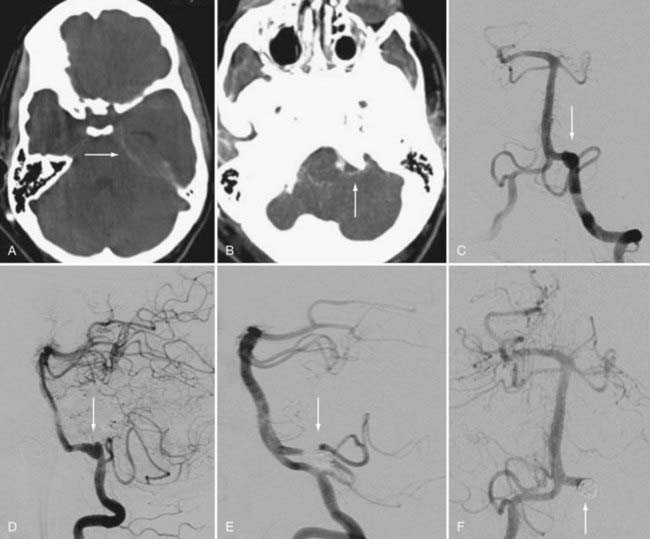

Aneurysms involving the origin of the PICA raise important concerns that can guide favorable management options (Fig. 377-1). A treatment rubric was proposed by Iihara and coworkers in which it was suggested that certain strategies could be used depending on the relationship between the origin of the PICA and the aneurysm sac.18 They proposed that if the aneurysm is separate from the origin of the PICA, internal occlusion should be the recommended treatment. For an aneurysm involving the origin of PICA and manifested as SAH, the suggested treatment is proximal occlusion and internal trapping. If the aneurysm incorporates the origin of PICA and does not involve SAH, BTO should be performed followed by occipital artery–PICA bypass. For the authors of the case series of 18 patients, the algorithm resulted in a favorable morbidity rate of 17% with no instances of PICA infarction and no deaths.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree