Location

Within NETs (%)

Within GEP-NETs

Incidence SEER (/100,000)

Incidence (% of primary site)

5-year OS (%)

GEP-NETs

67

5.25

<2

75–82

Gastric

9–20

0.3

1

45–64

Small intestine

39–42

1.1

37–52

62–71

Appendix

6

0.15

30

90

Colon

9–20

0.35

<1

67

Rectum

26

1.1

<1

90

Pancreas

7–12

0.5–1.0

1–2

27–38

Bronchopulmonary

27

0.46

<2

44–87

Other sitesa

6

0.38

Most of NETs are diagnosed at advanced stages. According to SEER data including 19,669 cases with NETs, 59.9 % of NETs arising in gastrointestinal tract were at the localized stage followed by regional (19.9 %) and distant stages (15.5 %) [6]. Data from Spanish registry showed that gastroenteropancreatic NETs were often diagnosed at advanced stage with 44.2 %, followed by localized and regional stages with 36.4 % and 14.2 %, respectively, and then unknown stage and undetermined cases with 5.3 % [7]. However, NETs originating in pancreas tend to be aggressive and about 60 % of these tumors are malignant at the time of diagnosis.

3.1.1 NETs of Gastrointestinal Tract (GT-NETs)

Although NETs have arisen from neuroendocrine cells located throughout the body including the lung, breast, ovary, and endometrium, gastrointestinal system is the most common localization of these tumors. The incidence of gastroenteropancreatic NETs (GEP-NETs) is similar in male and female [8, 9]. The incidence increases with age. Median age is lower in NETs arising from appendix and pancreas compared to those of other organs of gastrointestinal tract. The median age is less than 50 years for appendix and pancreatic NETs, but more than 60 for the others [9, 10]. Most of GEP-NETs are symptomatic and the most common symptoms were abdominal pain and weight loss.

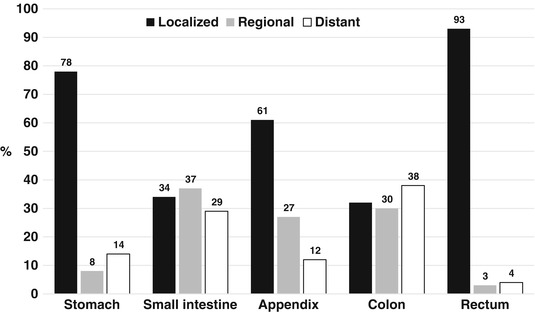

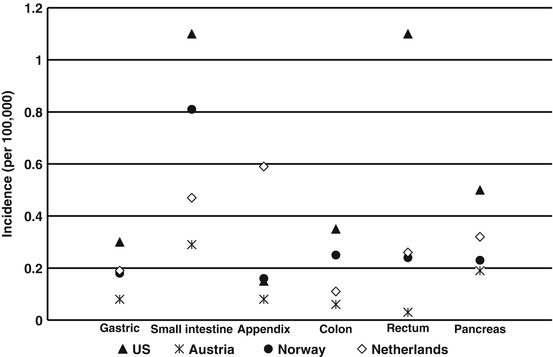

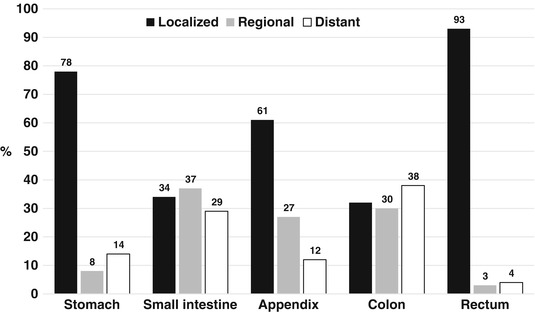

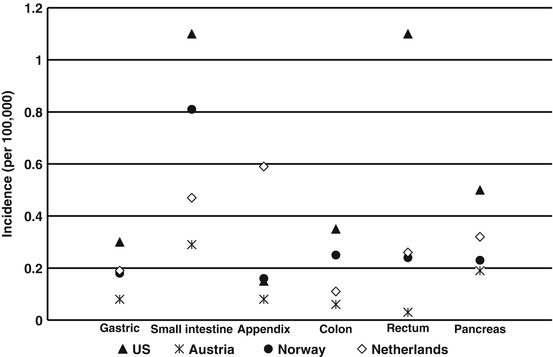

NETs of gastrointestinal system, accounting for approximately two-thirds of all NETs, are most commonly located in the gastric mucosa, the small intestine, the rectum, and the pancreas [11]. They comprise less than 2 % of gastrointestinal system tumors. GT-NETs are the second most common gastrointestinal tract tumors after colorectal cancer and more frequent than the other NETs [12]. Distribution and stages at the time of diagnosis of NETs arising in the gastrointestinal tract are presented in Figs. 3.1 and 3.2. Incidence rates of GEP-NETs in different populations are illustrated in Fig. 3.3.

Fig. 3.1

Distribution of NETs arising in the gastrointestinal tract

Fig. 3.2

Stage distribution of NETs arising in the gastrointestinal tract

Fig. 3.3

Incidence rates of GEP-NETs in different populations

In the developed countries, small bowel is the most common primary site of GEP-NETs [2, 13, 14]. They account for 39–42 % of all GEP-NETs followed by the rectum and the colon [11, 13, 14]. The ileum is the most common location of the small intestinal NETs [13]. In Western countries, the small intestinal NETs are more common than in Asian population [15]. The small bowel NETs slowly progress and usually present with advanced stages at diagnosis. Rectum is one of the most common localization of NETs arising in gastrointestinal system and accounts for 14 % of all NETs [11]. About 1 % of all rectal tumors are NETs [16]. However, NETs originated from colon represent about 8 % of NETs [11]. Cecum is the most common site for colonic NETs.

NETs originating in gastric mucosa are less common. It accounts for about 9–20 % of GEP-NETs and less than 1 % of all gastric tumors [11, 17, 18]. Recently, the incidence has been increased due to more widespread use of gastrointestinal endoscopy [19]. Gastric NETs are classified into three groups as types I, II, and III. The etiology and survival of these tumors are different. Type I gastric NETs, which are the most common gastric NETs (70–80 %), are associated with autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis and hypergastrinemia, whereas type II, which accounts for 5–6 % of gastric NETs, develops in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 1 [20–23]. Tumor size of type I and II gastric NETs is usually less than 1 cm and the prognosis is good. Type I gastric NETs are usually benign tumors. On the other hand, type III gastric NETs develop in normal gastric mucosa and are responsible for 14–25 % of gastric NETs. Their prognosis is worse than type I and II tumors [20, 22, 24].

In a multicenter registry study, the authors aimed to assess the prevalence and incidence of patients with GEP-NET in Asia-Pacific, Middle East, Turkey, and South Africa [9]. In contrast to the literature reporting the western population figures, pancreas and stomach were the most frequently reported primary sites (42 % and 17 %, respectively).

3.1.2 Pancreatic NETs (PaNETs)

Pancreatic NETs (PaNETs) are responsible for 1–2 % of all pancreatic neoplasms and the overall incidence is 0.5/100,000 people per year [25]. However, the incidence ranges from 0.8 to 10 % in autopsy series [26]. In developed countries, small intestine is the most frequent localization of NETs, but pancreas is the most common in the eastern population [9, 13, 14].

About 10–20 % of PaNETs are associated with MEN type 1 [27]. PaNETs may be functional by secreting various hormones and peptides. The most commonly observed functional tumor is insulinoma with 70–80 % of all PaNETs, but only less than 10 % of insulinoma is malignant [28]. Mostly, the other types of PaNETs such as glucagonoma, VIPoma, and gastrinoma tend to be malignant. PaNETs are usually characterized as slow growing and indolent tumors.

3.1.3 Bronchopulmonary NETs

Bronchopulmonary NETs are classified as three main entities such as carcinoid tumors (typical and atypical carcinoids), large cell NETs, and small cell carcinoma [29]. Well-differentiated low-grade NETs are known as typical carcinoids, and intermediate-grade NETs are atypical carcinoids. Prognosis of typical carcinoids is excellent. Large cell NETs and small cell NETs are considered as poorly differentiated NETs and are known to have a worse prognosis. Stage distribution of typical and atypical bronchopulmonary carcinoids is shown in Fig. 3.4.

Fig. 3.4

Stage distribution of typical and atypical bronchopulmonary carcinoids

The second most common location of NETs after gastrointestinal tract is the bronchopulmonary system and it accounts for about 27 % of all NETs [11]. Less than 2 % of all lung tumors are NETs including typical and atypical carcinoids. Contrary to small cell lung cancer, the lung carcinoids occur in younger and nonsmoker patients [30]. Large cell NETs account for 3 % of all lung cancers [30]. Incidence of bronchopulmonary NETs increases linearly similar to the GEP-NETs. Bronchopulmonary NETs may present with dyspnea, cough, and hemoptysis. In some patients, they are discovered incidentally. Bronchopulmonary carcinoid tumors can be cured with surgical excision.

3.2 Survival

NETs are very heterogeneous tumors. Most of NETs are well or moderately differentiated tumors, with relatively indolent course and slow growth. Thus, overall survival of NETs is different for each tumor. Overall survival in patients who have poorly differentiated tumors and who have distant metastases is shorter than those who have well-differentiated and localized tumors. For example, median survival in patients with distant metastases for nonfunctioning PaNETs was shorter with 23 months than localized and regional disease (124 and 70 months, respectively) [2]. The survival has improved in the last two decades. Prognostic factors influencing survival are known as distant metastasis, poorly differentiated tumor, grade, age, number of liver metastasis, extrahepatic metastasis, and the presence of positive surgical margin [2, 30–35].

While the best survival rates are observed in patients with NETs arising in the rectum and appendix, the prognosis of colonic NETs is worse. The 5-year disease-specific survival rates are about 96 % for rectum and 90 % for appendix [6, 11, 36], while the survival rates are lower in the other GEP-NETs including small intestine (86 %) and colon (67 %). For NETs arising in the small bowel, the 5-year survival varies between 60 and 75 % [11, 37–39]. However, the best survival rates among small intestinal NETs were reported for appendiceal NETs. The prognosis is excellent with the 5-year disease-free survival rates of 89–95 % [6, 38, 40]. In a published study from Denmark, the 5-year survival rate was found to be 77 % in patients with small intestinal NETs [41]. Similarly, the 5-year survival exceeds about 60 % in patients with operable PaNETs [26, 42, 43]. Different survival rates are observed for each country. The 5-year overall survival was reported as 71 % in the US-based SEER database [44]. Higher rates were reported from Italy and Spain with 72–89 %, while in France they were lower with 56 % [7, 45, 46].

For type I gastric NETs, the prognosis is very good and 5-year survival is about 95 % [47]. However, the survival rates for type II and III gastric NETs are 70 % and 35 %, respectively. The survival rates in the USA have been reportedly higher when compared to those of Europe [6, 7, 45, 48]. While the 5-year survival rate based on the SEER database was 75–82 %, the rates were 61 % in Spain, 63 % in Italy, and 45 % in Norway.

Survival rates are lower in PaNETs than other GEP-NETs. The survival is about 27–38 % in advanced stage PaNETs [2, 13, 26, 48, 49]. In patients with functioning PaNETs, the survival is better [50]. Higher 5-year survival rates have been reported from Norway with 43 % and from Spain with 78 % [7, 48]. Incidence of NETs arising in GEP and bronchopulmonary systems has a marked increase in male and female in the last 30 years worldwide.

3.3 Factors Associated with NETs

3.3.1 Age and Gender

Incidence of NETs increases with age. Although the disease can appear at all ages, it peaks between sixth and seventh decades. NETs are rarely seen in pediatric patients. Median age at the time of presentation is 60 years [2, 26, 40, 49, 51, 52]. While incidence rates are similar between both sexes in the USA [11, 53, 54], some NETs such as NETs at rectal location are slightly higher in men than in women [55, 56]. The small intestinal NETs and PaNETs are more common in males [11, 26, 45, 46, 57, 58], but low-grade NETs in the appendix and bronchopulmonary appear to be more often in women compared with men [10].

3.3.2 Race and Ethnicity

According to SEER database, NETs such as carcinoid tumors in the appendix are more prominent in whites. However, certain NETs such as those of the small bowel and PaNETs are more common in African-Americans and Asian population within the USA [2, 11, 26, 48]. Incidence of rectal NETs is about three times higher in Asian than non-Asian populations [11]. These tumors are also more common for both males and females in blacks compared to whites [2, 11, 48, 59].

3.3.3 Genetic and Family History

Although majority of NETs occur sporadically, some may be hereditary and can appear with genetic syndromes such as MEN type 1, MEN type 2, and von Hippel-Lindau disease [2, 18]. The familial von Hippel-Lindau disease-related PaNETs are not as high as MEN type 1 [60, 61]. NETs may also be associated with certain allelic losses. For example, loss of 22q13.1-q13.31 is considered to have associated with development of insulinoma [62].

3.3.4 Occupational Risks

The association between occupational exposure and carcinoid tumors has been investigated in epidemiological studies. In a multicenter population-based case-control study, the authors reported that employment in industry of food and beverages (odds ratio, 8.2; 95 % CI, 1.9–34.9) and in the manufacture of motor vehicle bodies (odds ratio, 5.2; 95 % CI, 1.2–22.4), footwear (odds ratio, 3.9; 95 % CI, 1.9–16.1), and metal structure footwear (odds ratio, 3.3; 95 % CI, 1.0–10.4) is associated with the increased risk of small intestine carcinoid [65]. The results of a large prospective study which evaluated risk factors for adenocarcinomas and malignant carcinoid tumors of the small intestine suggested that age (HR for ≥ 65 vs. 50–55 years, 3.31; 95 % CI, 1.51, 7.28), male sex (HR = 1.4; 95 % CI, 1.0–2.1), body mass index (BMI, HR for ≥ 35 kg/m2 vs. <25 kg/m2, 1.9; 95 % CI, 1.1, 3.6), and current menopausal hormone therapy use (HR = 1.9, 95 % CI, 1.1, 3.5) were positively associated with malignant carcinoids [66].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree